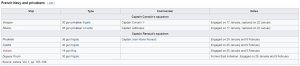

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

23 January 1781 - HMS Culloden (1776 - 74), Cptn. Balfour, wrecked on the east end of Long Island in a gale.

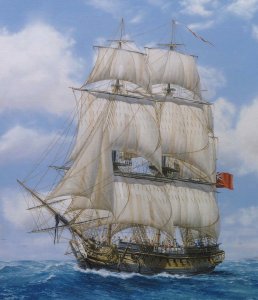

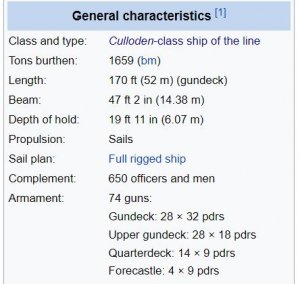

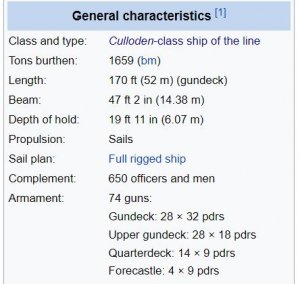

HMS Culloden was a 74-gun Culloden-class third-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, built at Deptford Dockyard, England, and launched on 18 May 1776. She was the fourth warship to be named after the Battle of Culloden, which took place in Scotland in 1746 and saw the defeat of the Jacobite rising.

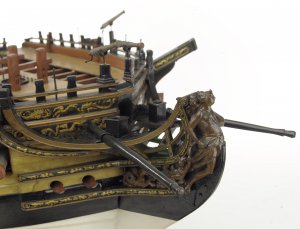

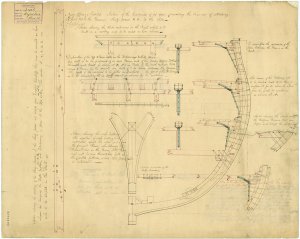

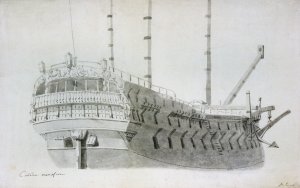

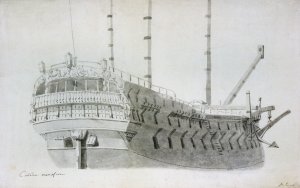

Inscribed in black ink 'Culloden man of war', lower left, and signed 'D Serres', lower right, in a browner ink. The particular interest of this drawing is that it is clearly modelled on the similar studies of the van de Veldes, especially Willem the Elder, a century earlier. Serres' considerable collection of other artists' drawings included a number by the van de Veldes of which the Museum has at least two (Robinson I: 294 and Robinson II, 1026). The Navy had three 74-gun ships called 'Culloden' in rapid succession, the name commemorating the defeat of the Scottish Jacobites there by the 'Butcher' Duke of Cumberland in 1746. The first was built in 1747 and sold in 1770; the second built in 1776 and wrecked on Long Island in 1781, and the third built in 1783 and broken up in 1813. The Museum has a detailed drawing of the stern of the 1776 ship as part of her sheer draught (ZAZ0978) which shows that she had eight stern windows to her great cabin, two arched ones on each side on the open quarter-deck gallery above and separate quarter carvings on each level at either side. That is not what is shown here: there are only seven great cabin windows, no arched ones above and the quarter figures - apparently of contemporary soldiers- bracket both deck levels. The ship shown is therefore the 'Culloden' of 1783, of which the Museum also has a few plans but none showing the stern detail.

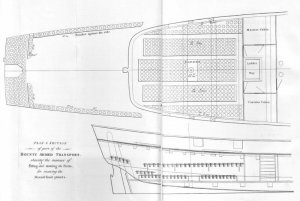

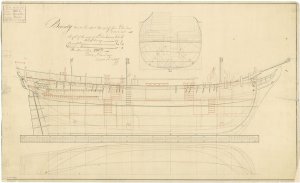

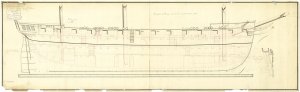

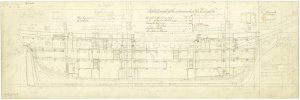

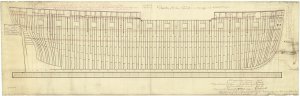

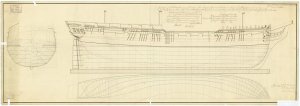

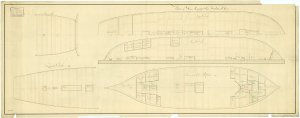

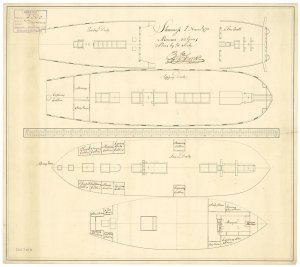

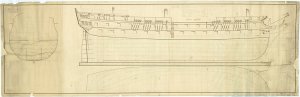

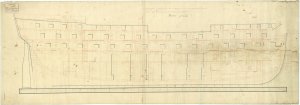

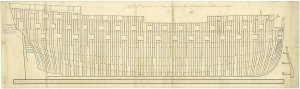

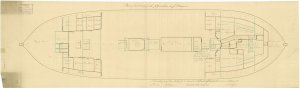

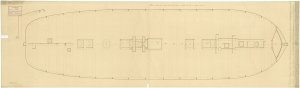

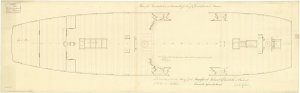

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name on the counter, sheer lines with inboard detail and stern quarter decoration and figurehead, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Culloden' (1776), a 74-gun, Third Rate, two-decker as built at Deptford Dockyard.

She served with the Channel Fleet during the American War of Independence, seeing action at the Battle of Cape St Vincent, before being sent out to the West Indies. Her stay there was brief, sailing for New York City with Admiral Rodney in August 1780 to join the North American station. The ship's specific duties were to blockade the French at Newport, Rhode Island where a French army of 6,000 had disembarked in July 1780.[citation needed]

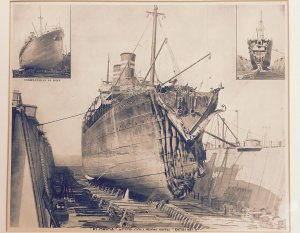

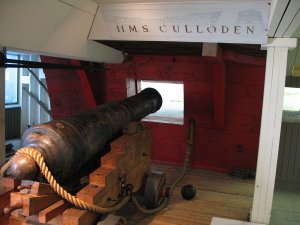

Diorama of Culloden wreck at the Marine Museum

On 23 January 1781, while trying to intercept French ships attempting to run the blockade at Newport, Rhode Island, Culloden encountered severe weather and ran aground at North Neck Point (Will's Point) in Montauk. All attempts to refloat the vessel were unsuccessful,[citation needed] but all the crew were saved, and Culloden's masts were taken aboard HMS Bedford. The area is today known as Culloden Point.

Salvage operations

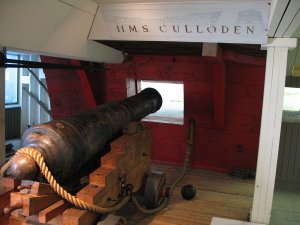

The British conducted salvage operations on the ship throughout March, retrieving all 28 eighteen-pounder guns from the upper deck, and all 18 nine-pounders from the quarterdeck. The larger cannons were pushed into the sea and the ship was then burned to the waterline and abandoned.

On 24 July 1781, Joseph Woodbridge of Groton, Connecticut sent a letter to George Washington offering to sell him sixteen 32-pounders from the wreck, and on 14 July 1815, Samuel Jeffers arrived in Newport, Rhode Island with 12 tons of pig iron and a 32-pounder from the wreck.

In 1971 Henry W. Moeller, an undersea archaeologist associated with Dowling College, discovered the keel and large wooden beams resting in between 10 ft (3.0 m) and 15 ft (4.6 m) of water 150 ft (46 m) off Culloden Point. A gudgeon imprinted with the name Culloden was recovered. Subsequent recovery efforts brought up another 32-pounder cannon as well as copper sheathing. A sketch of the outline of the ruins showed the ship resting on a large boulder.

Cannon retrieved from Culloden on display at the East Hampton Marine Museum in Amagansett, New York

National Register of Historic Places

Since 1979 the wreck site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which prohibits SCUBA divers from taking artifacts from, or otherwise disturbing the wreck. The designated area is a 'circle with a radius of approximately 200 feet (61 m) and a centre at the point formed by UTM co-ordinates 19/2 51 370/45 50 810.

The application notes that in addition to Revolutionary War connections, the shipwreck is important for showing the British state-of-the-art copper sheathing of the ship as well as the possibility that it may reveal problems about corruption in the British shipyards at the time. The application notes:

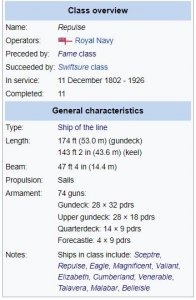

The Culloden-class ships of the line were a class of eight 74-gun third rates, designed for the Royal Navy by Sir Thomas Slade. The Cullodens were the last class of 74 Slade designed before his death in 1771.

Ships

Builder: Deptford Dockyard

Ordered: 30 November 1769

Launched: 18 May 1776

Fate: Wrecked, 1781

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 23 August 1781

Launched: 13 November 1783

Fate: Broken up, 1814

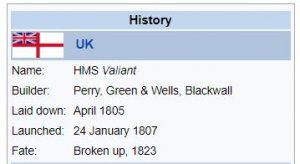

Builder: Perry, Wells & Green, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 9 August 1781

Launched: 19 April 1784

Fate: Wrecked, 1804

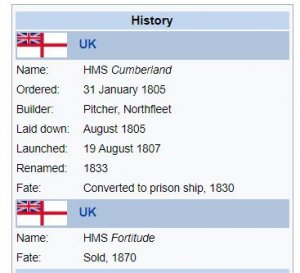

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 13 December 1781

Launched: 28 March 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1836

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 28 December 1781

Launched: 27 April 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1803

Builder: Randall, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 12 July 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1850

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 15 April 1786

Fate: Captured, 1801

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 11 July 1780

Launched: 25 September 1786

Fate: Broken up, 1814

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Culloden_(1776)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culloden-class_ship_of_the_line

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collec...el-305581;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=C

23 January 1781 - HMS Culloden (1776 - 74), Cptn. Balfour, wrecked on the east end of Long Island in a gale.

HMS Culloden was a 74-gun Culloden-class third-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, built at Deptford Dockyard, England, and launched on 18 May 1776. She was the fourth warship to be named after the Battle of Culloden, which took place in Scotland in 1746 and saw the defeat of the Jacobite rising.

Inscribed in black ink 'Culloden man of war', lower left, and signed 'D Serres', lower right, in a browner ink. The particular interest of this drawing is that it is clearly modelled on the similar studies of the van de Veldes, especially Willem the Elder, a century earlier. Serres' considerable collection of other artists' drawings included a number by the van de Veldes of which the Museum has at least two (Robinson I: 294 and Robinson II, 1026). The Navy had three 74-gun ships called 'Culloden' in rapid succession, the name commemorating the defeat of the Scottish Jacobites there by the 'Butcher' Duke of Cumberland in 1746. The first was built in 1747 and sold in 1770; the second built in 1776 and wrecked on Long Island in 1781, and the third built in 1783 and broken up in 1813. The Museum has a detailed drawing of the stern of the 1776 ship as part of her sheer draught (ZAZ0978) which shows that she had eight stern windows to her great cabin, two arched ones on each side on the open quarter-deck gallery above and separate quarter carvings on each level at either side. That is not what is shown here: there are only seven great cabin windows, no arched ones above and the quarter figures - apparently of contemporary soldiers- bracket both deck levels. The ship shown is therefore the 'Culloden' of 1783, of which the Museum also has a few plans but none showing the stern detail.

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name on the counter, sheer lines with inboard detail and stern quarter decoration and figurehead, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Culloden' (1776), a 74-gun, Third Rate, two-decker as built at Deptford Dockyard.

She served with the Channel Fleet during the American War of Independence, seeing action at the Battle of Cape St Vincent, before being sent out to the West Indies. Her stay there was brief, sailing for New York City with Admiral Rodney in August 1780 to join the North American station. The ship's specific duties were to blockade the French at Newport, Rhode Island where a French army of 6,000 had disembarked in July 1780.[citation needed]

Diorama of Culloden wreck at the Marine Museum

On 23 January 1781, while trying to intercept French ships attempting to run the blockade at Newport, Rhode Island, Culloden encountered severe weather and ran aground at North Neck Point (Will's Point) in Montauk. All attempts to refloat the vessel were unsuccessful,[citation needed] but all the crew were saved, and Culloden's masts were taken aboard HMS Bedford. The area is today known as Culloden Point.

Salvage operations

The British conducted salvage operations on the ship throughout March, retrieving all 28 eighteen-pounder guns from the upper deck, and all 18 nine-pounders from the quarterdeck. The larger cannons were pushed into the sea and the ship was then burned to the waterline and abandoned.

On 24 July 1781, Joseph Woodbridge of Groton, Connecticut sent a letter to George Washington offering to sell him sixteen 32-pounders from the wreck, and on 14 July 1815, Samuel Jeffers arrived in Newport, Rhode Island with 12 tons of pig iron and a 32-pounder from the wreck.

In 1971 Henry W. Moeller, an undersea archaeologist associated with Dowling College, discovered the keel and large wooden beams resting in between 10 ft (3.0 m) and 15 ft (4.6 m) of water 150 ft (46 m) off Culloden Point. A gudgeon imprinted with the name Culloden was recovered. Subsequent recovery efforts brought up another 32-pounder cannon as well as copper sheathing. A sketch of the outline of the ruins showed the ship resting on a large boulder.

Cannon retrieved from Culloden on display at the East Hampton Marine Museum in Amagansett, New York

National Register of Historic Places

Since 1979 the wreck site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which prohibits SCUBA divers from taking artifacts from, or otherwise disturbing the wreck. The designated area is a 'circle with a radius of approximately 200 feet (61 m) and a centre at the point formed by UTM co-ordinates 19/2 51 370/45 50 810.

The application notes that in addition to Revolutionary War connections, the shipwreck is important for showing the British state-of-the-art copper sheathing of the ship as well as the possibility that it may reveal problems about corruption in the British shipyards at the time. The application notes:

Finally, the Culloden shipwreck site may provide material insight into the political conditions existent in the British Admiralty during this period. James [1926:7-18) has written describing the strength and organization of the Royal Navy at the end of the Seven Years' War (1755–1762) and its subsequent dissipation between 1771 and 1778 through mismanagement and corruption under Lord Sandwich's control of the Admiralty. Construction of the Culloden occurred during the period that Admiralty corruption was at its height. Therefore, the Culloden may reflect in material terms corrupt practices plaguing England's shipyards at the time. Construction shortcuts and the manufacturing of parts that do not meet specifications have long characterized the defense industry of all nations. The Culloden shipwreck site may provide data illustrating this activity.

The Culloden-class ships of the line were a class of eight 74-gun third rates, designed for the Royal Navy by Sir Thomas Slade. The Cullodens were the last class of 74 Slade designed before his death in 1771.

Ships

Builder: Deptford Dockyard

Ordered: 30 November 1769

Launched: 18 May 1776

Fate: Wrecked, 1781

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 23 August 1781

Launched: 13 November 1783

Fate: Broken up, 1814

Builder: Perry, Wells & Green, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 9 August 1781

Launched: 19 April 1784

Fate: Wrecked, 1804

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 13 December 1781

Launched: 28 March 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1836

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 28 December 1781

Launched: 27 April 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1803

Builder: Randall, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 12 July 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1850

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 15 April 1786

Fate: Captured, 1801

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 11 July 1780

Launched: 25 September 1786

Fate: Broken up, 1814

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Culloden_(1776)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culloden-class_ship_of_the_line

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collec...el-305581;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=C