Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

4 June 1898 – Launch of HMS Highflyer, the lead ship of the Highflyer-class protected cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the 1890s

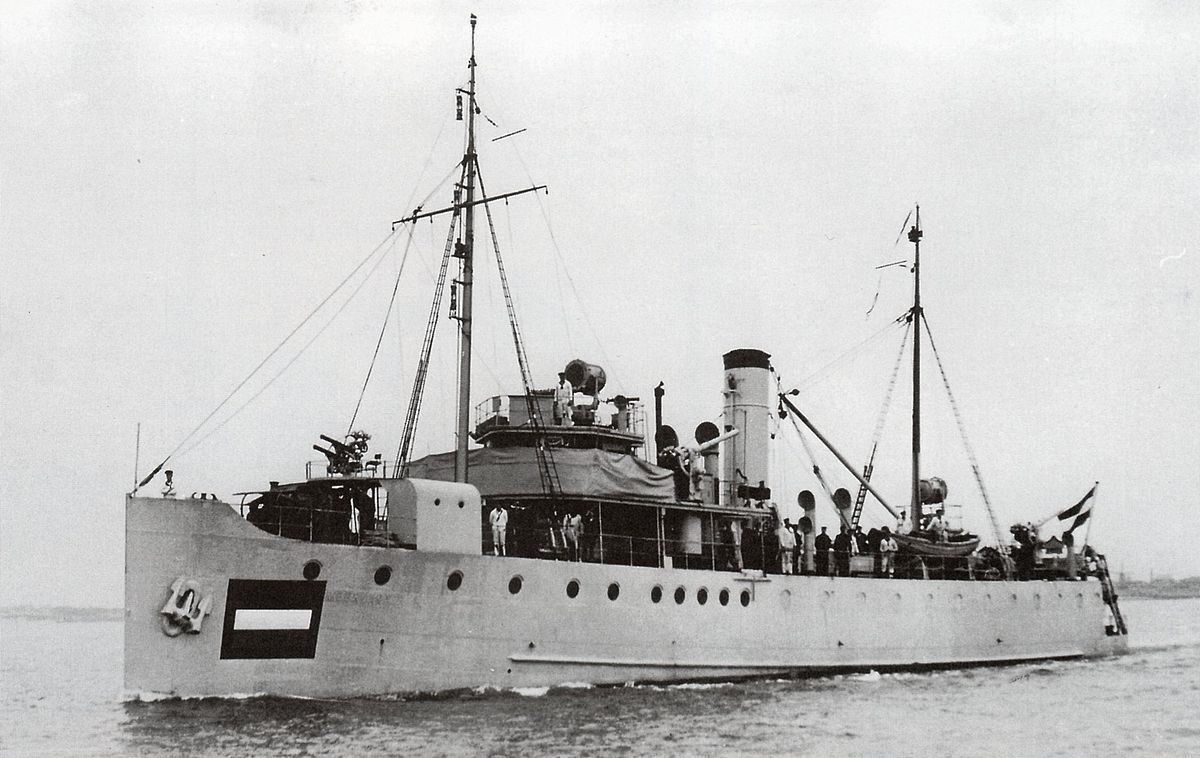

HMS Highflyer was the lead ship of the Highflyer-class protected cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the 1890s. She spent her early career as flagship for the East Indies and North America and West Indies Stations. She was reduced to reserve in 1908 before again becoming the flagship in the East Indies in 1911. She returned home two years later and became a training ship. When World War I began in August 1914, she was assigned to the 9th Cruiser Squadron in the Central Atlantic to intercept German commerce raiders and protect Allied shipping.

Days after the war began, she intercepted a Dutch ship carrying German troops and gold. She then sank the German armed merchant cruiser SMS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse off the coast of Spanish Sahara. Highflyer spent most of the rest of the war on convoy escort duties and was present in Halifax during the Halifax in late 1917. She became flagship of the East Indies Station after the war. The ship was sold for scrap in 1921.

in late 1917. She became flagship of the East Indies Station after the war. The ship was sold for scrap in 1921.

Design and description

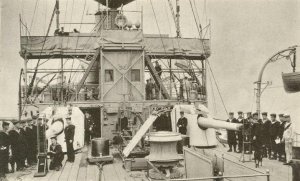

The two 6-inch guns on her sister ship Hermes's quarterdeck

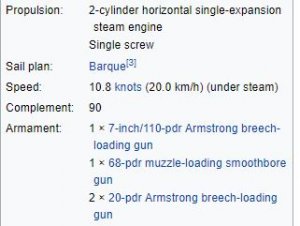

Highflyer was designed to displace 5,650 long tons (5,740 t). The ship had an overall length of 372 feet (113.4 m), a beam of 54 feet (16.5 m) and a draught of 29 feet 6 inches (9.0 m). She was powered by two 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one shaft, which produced a total of 10,000 indicated horsepower(7,500 kW) designed to give a maximum speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph). Highflyer reached a speed of 20.1 knots (37.2 km/h; 23.1 mph) from 10,344 ihp (7,714 kW), during her sea trials. The engines were powered by 18 Belleville boilers. She carried a maximum of 1,125 long tons (1,143 t) of coal and her complement consisted of 470 officers and enlisted men.

Her main armament consisted of 11 quick-firing (QF) 6-inch (152 mm) Mk I guns. One gun was mounted on the forecastle and two others were positioned on the quarterdeck. The remaining eight guns were placed port and starboard amidships. They had a maximum range of approximately 10,000 yards (9,100 m) with their 100-pound (45 kg) shells. Eight quick-firing (QF)12-pounder 12 cwt guns were fitted for defence against torpedo boats. One additional 12-pounder 8 cwt gun could be dismounted for service ashore.[2]Highflyer also carried six 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and two submerged 18-inch torpedo tubes.

The ship's protective deck armour ranged in thickness from 1.5 to 3 inches (38 to 76 mm). The engine hatches were protected by 5-inch (127 mm) of armour. The main guns were fitted with 3-inch gun shields and the conning tower had armour 6 inches thick.

Construction and service

Highflyer was laid down by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering at their shipyard in Govan, Scotland on 7 June 1897, and launched on 4 June 1898, when she was christened by Mrs. Elgar, wife of Francis Elgar, a director of the shipbuilding company, who held a speech. She was completed on 7 December 1899 and commissioned by Captain Frederic Brock for the Training squadron.

In February 1900 she was re-commissioned to serve in the Indian Ocean as the flagship of Rear-Admiral Day Bosanquet, Commander-in-Chief, East Indies Station.[8] Captain Arthur Christian was appointed in command of the ship in June 1902, as Flag captain to Rear-Admiral Charles Carter Drury, who succeeded Bosanquet as Commander-in-Chief of the Station. She was at Mauritius in August 1902 where she took part in local celebrations for the Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, and the following month visited Trincomalee.

She was transferred to the North America and West Indies Station in 1904 and served as its flagship until November 1906 when returned to the East Indies Station. Highflyer was placed in reserve at Devonport Royal Dockyard in 1908 and then assigned to the reserve Third Fleet in 1910. She was again assigned as the flagship of the East Indies Station in February 1911 until departing for home in April 1913. In August 1913 she became the training ship for Special Entry Cadets.

In August 1914 she was allocated to the 9th Cruiser Squadron, under Rear Admiral John de Robeck, on the Finisterre station. She left Plymouth on 4 August, in the company of the admiral on HMS Vindictive. The Dutch ocean liner Tubantia, was returning from South America when the war began with £500,000 in gold destined for banks in London, a large portion of which was intended for the German Bank of London. She was also carrying about 150 German reservists in steerage and a cargo of grain destined for Germany. She was stopped and boarded by an officer and crewmen from Highflyer, and escorted into port at Plymouth.

She was then transferred to the Cape Verde station, to support Rear Admiral Archibald Stoddart's 5th Cruiser Squadron in the hunt for the German armed merchant cruiser SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She had been sighted at Río de Oro, a Spanish anchorage on the Saharan coast. On 26 August Highflyer found the German ship taking on coal from three colliers. Highflyer's captain demanded that the Germans surrender. The captain of Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse claimed the protection of neutral waters, but as he was breaking that neutrality himself by staying for more than a week, his claim was denied. Fighting broke out at 15:10, and lasted until 16:45, when the crew of Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse abandoned ship and escaped to the shore. The German ship was sunk, with the British losing one man killed (Richard James Lobb) and five injured in the engagement. In mid-1916 the Prize Court awarded the crew of Highflyer ₤2,680 for the sinking of the German ship.

On 15 October Highflyer briefly became the flagship of the Cape Verde station, when Stoddard was ordered to Pernambuco, Brazil. Later in the same month she was ordered to accompany the transport ships carrying the Cape garrison back to Britain and then searched the Atlantic coast of North Africa for the German light cruiser SMS Karlsruhe. After the Battle of Coronel in November, Highflyer came back under the control of Admiral de Robeck, as part of a squadron formed to guard West Africa against Admiral Maximilian von Spee. This squadron, consisting of the cruisers HMS Warrior, HMS Black Prince, HMS Donegal and Highflyer was in place off Sierra Leone from 12 November, but was soon dispersed after the battle of the Falklands in December. Highflyer then took part in the search for the commerce raider Kronprinz Wilhelm, coming close to catching her in January 1915. She remained on the West Africa station until she was transferred to the North America and West Indies Squadron in 1917.

This was the period of unrestricted submarine warfare, and the Admiralty eventually decided to operate a convoy system in the North Atlantic. On 10 July 1917 Highflyer provided the escort for convoy HS 1, the first convoy to sail from Canada to Britain. She was in Halifax for the Halifax on 6 December 1917 when the French ammunition ship SS Mont-Blanc exploded destroying much of the city. Highflyer launched a whaleboat before the explosion to investigate the fire aboard Mont-Blanc; the ship exploded before they reached her, killing nine of ten men in the boat. Many aboard the ship were injured by blast and she was lightly damaged herself. Her crew provided medical care to survivors and helped to clear debris. She departed Halifax on 11 December to escort a convoy to Plymouth.

on 6 December 1917 when the French ammunition ship SS Mont-Blanc exploded destroying much of the city. Highflyer launched a whaleboat before the explosion to investigate the fire aboard Mont-Blanc; the ship exploded before they reached her, killing nine of ten men in the boat. Many aboard the ship were injured by blast and she was lightly damaged herself. Her crew provided medical care to survivors and helped to clear debris. She departed Halifax on 11 December to escort a convoy to Plymouth.

Highflyer returned to the East Indies Station in 1918 and was paid off at Bombay in March 1919. She was recommissioned in July as the station flagship and served until she was paid off in early 1921 and sold for scrap there on 10 June.

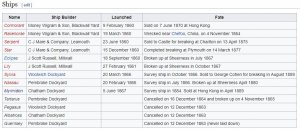

The Highflyer-class cruisers were a group of three second-class protected cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the late 1890s.

Ships

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

4 June 1898 – Launch of HMS Highflyer, the lead ship of the Highflyer-class protected cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the 1890s

HMS Highflyer was the lead ship of the Highflyer-class protected cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the 1890s. She spent her early career as flagship for the East Indies and North America and West Indies Stations. She was reduced to reserve in 1908 before again becoming the flagship in the East Indies in 1911. She returned home two years later and became a training ship. When World War I began in August 1914, she was assigned to the 9th Cruiser Squadron in the Central Atlantic to intercept German commerce raiders and protect Allied shipping.

Days after the war began, she intercepted a Dutch ship carrying German troops and gold. She then sank the German armed merchant cruiser SMS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse off the coast of Spanish Sahara. Highflyer spent most of the rest of the war on convoy escort duties and was present in Halifax during the Halifax

in late 1917. She became flagship of the East Indies Station after the war. The ship was sold for scrap in 1921.

in late 1917. She became flagship of the East Indies Station after the war. The ship was sold for scrap in 1921.Design and description

The two 6-inch guns on her sister ship Hermes's quarterdeck

Highflyer was designed to displace 5,650 long tons (5,740 t). The ship had an overall length of 372 feet (113.4 m), a beam of 54 feet (16.5 m) and a draught of 29 feet 6 inches (9.0 m). She was powered by two 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one shaft, which produced a total of 10,000 indicated horsepower(7,500 kW) designed to give a maximum speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph). Highflyer reached a speed of 20.1 knots (37.2 km/h; 23.1 mph) from 10,344 ihp (7,714 kW), during her sea trials. The engines were powered by 18 Belleville boilers. She carried a maximum of 1,125 long tons (1,143 t) of coal and her complement consisted of 470 officers and enlisted men.

Her main armament consisted of 11 quick-firing (QF) 6-inch (152 mm) Mk I guns. One gun was mounted on the forecastle and two others were positioned on the quarterdeck. The remaining eight guns were placed port and starboard amidships. They had a maximum range of approximately 10,000 yards (9,100 m) with their 100-pound (45 kg) shells. Eight quick-firing (QF)12-pounder 12 cwt guns were fitted for defence against torpedo boats. One additional 12-pounder 8 cwt gun could be dismounted for service ashore.[2]Highflyer also carried six 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and two submerged 18-inch torpedo tubes.

The ship's protective deck armour ranged in thickness from 1.5 to 3 inches (38 to 76 mm). The engine hatches were protected by 5-inch (127 mm) of armour. The main guns were fitted with 3-inch gun shields and the conning tower had armour 6 inches thick.

Construction and service

Highflyer was laid down by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering at their shipyard in Govan, Scotland on 7 June 1897, and launched on 4 June 1898, when she was christened by Mrs. Elgar, wife of Francis Elgar, a director of the shipbuilding company, who held a speech. She was completed on 7 December 1899 and commissioned by Captain Frederic Brock for the Training squadron.

In February 1900 she was re-commissioned to serve in the Indian Ocean as the flagship of Rear-Admiral Day Bosanquet, Commander-in-Chief, East Indies Station.[8] Captain Arthur Christian was appointed in command of the ship in June 1902, as Flag captain to Rear-Admiral Charles Carter Drury, who succeeded Bosanquet as Commander-in-Chief of the Station. She was at Mauritius in August 1902 where she took part in local celebrations for the Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, and the following month visited Trincomalee.

She was transferred to the North America and West Indies Station in 1904 and served as its flagship until November 1906 when returned to the East Indies Station. Highflyer was placed in reserve at Devonport Royal Dockyard in 1908 and then assigned to the reserve Third Fleet in 1910. She was again assigned as the flagship of the East Indies Station in February 1911 until departing for home in April 1913. In August 1913 she became the training ship for Special Entry Cadets.

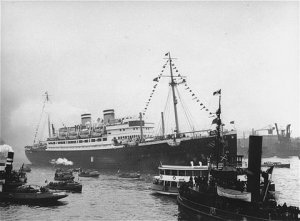

In August 1914 she was allocated to the 9th Cruiser Squadron, under Rear Admiral John de Robeck, on the Finisterre station. She left Plymouth on 4 August, in the company of the admiral on HMS Vindictive. The Dutch ocean liner Tubantia, was returning from South America when the war began with £500,000 in gold destined for banks in London, a large portion of which was intended for the German Bank of London. She was also carrying about 150 German reservists in steerage and a cargo of grain destined for Germany. She was stopped and boarded by an officer and crewmen from Highflyer, and escorted into port at Plymouth.

She was then transferred to the Cape Verde station, to support Rear Admiral Archibald Stoddart's 5th Cruiser Squadron in the hunt for the German armed merchant cruiser SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She had been sighted at Río de Oro, a Spanish anchorage on the Saharan coast. On 26 August Highflyer found the German ship taking on coal from three colliers. Highflyer's captain demanded that the Germans surrender. The captain of Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse claimed the protection of neutral waters, but as he was breaking that neutrality himself by staying for more than a week, his claim was denied. Fighting broke out at 15:10, and lasted until 16:45, when the crew of Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse abandoned ship and escaped to the shore. The German ship was sunk, with the British losing one man killed (Richard James Lobb) and five injured in the engagement. In mid-1916 the Prize Court awarded the crew of Highflyer ₤2,680 for the sinking of the German ship.

On 15 October Highflyer briefly became the flagship of the Cape Verde station, when Stoddard was ordered to Pernambuco, Brazil. Later in the same month she was ordered to accompany the transport ships carrying the Cape garrison back to Britain and then searched the Atlantic coast of North Africa for the German light cruiser SMS Karlsruhe. After the Battle of Coronel in November, Highflyer came back under the control of Admiral de Robeck, as part of a squadron formed to guard West Africa against Admiral Maximilian von Spee. This squadron, consisting of the cruisers HMS Warrior, HMS Black Prince, HMS Donegal and Highflyer was in place off Sierra Leone from 12 November, but was soon dispersed after the battle of the Falklands in December. Highflyer then took part in the search for the commerce raider Kronprinz Wilhelm, coming close to catching her in January 1915. She remained on the West Africa station until she was transferred to the North America and West Indies Squadron in 1917.

This was the period of unrestricted submarine warfare, and the Admiralty eventually decided to operate a convoy system in the North Atlantic. On 10 July 1917 Highflyer provided the escort for convoy HS 1, the first convoy to sail from Canada to Britain. She was in Halifax for the Halifax

on 6 December 1917 when the French ammunition ship SS Mont-Blanc exploded destroying much of the city. Highflyer launched a whaleboat before the explosion to investigate the fire aboard Mont-Blanc; the ship exploded before they reached her, killing nine of ten men in the boat. Many aboard the ship were injured by blast and she was lightly damaged herself. Her crew provided medical care to survivors and helped to clear debris. She departed Halifax on 11 December to escort a convoy to Plymouth.

on 6 December 1917 when the French ammunition ship SS Mont-Blanc exploded destroying much of the city. Highflyer launched a whaleboat before the explosion to investigate the fire aboard Mont-Blanc; the ship exploded before they reached her, killing nine of ten men in the boat. Many aboard the ship were injured by blast and she was lightly damaged herself. Her crew provided medical care to survivors and helped to clear debris. She departed Halifax on 11 December to escort a convoy to Plymouth.Highflyer returned to the East Indies Station in 1918 and was paid off at Bombay in March 1919. She was recommissioned in July as the station flagship and served until she was paid off in early 1921 and sold for scrap there on 10 June.

The Highflyer-class cruisers were a group of three second-class protected cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the late 1890s.

Ships

- HMS Highflyer - launched on 4 June 1898, she served on numerous stations and hunted commerce raiders. She was sold for scrapping 10 June 1921, by then the last Victorian era cruiser in service with the Royal Navy.

- HMS Hermes - launched on 7 April 1898, she was converted to a seaplane carrier in 1913, and sunk on 31 October 1914 by U 27

- HMS Hyacinth - launched on 27 October 1898, she served on southern stations in the First World War, and assisted in the blockade of SMS Königsberg. She was sold for scrapping on 11 October 1923.

HMS Highflyer (1898) - Wikipedia

Highflyer-class cruiser - Wikipedia

Last edited by a moderator:

bury (DE-133) working to secure a tow line to the bow of the captured German submarine U-505, 4 June 1944. Note the large U.S. flag flying from the submarine's periscope.

bury (DE-133) working to secure a tow line to the bow of the captured German submarine U-505, 4 June 1944. Note the large U.S. flag flying from the submarine's periscope.