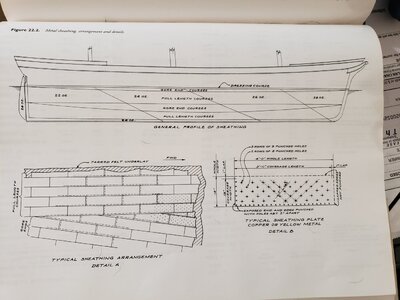

I'm investigating coppering the Discovery1789. I found an article on "Academia" called "The Introduction and Use of Copper Sheathing" by Mark Staniforth. In it he states that merchant ships were coppered starting where the stem meets the stern. This way the joints face down and to the stern. He also states that the Royal Navy has the joints facing up and to the stern. This may not sound too important, but the merchant way ends up with the coppering rows in a big arc at the waterline and the Navy way has the top row as a nice straight line. I'm assuming that to get the joint facing up, the Navy would start plating at the waterline at the stern and work down.

I just looked at Goodwins "English Man of War" and he says (Pg 225 Fig 10/1) that the joints face down and back on the Navy ships.

Does anyone have a little more info on this?

I just looked at Goodwins "English Man of War" and he says (Pg 225 Fig 10/1) that the joints face down and back on the Navy ships.

Does anyone have a little more info on this?