.

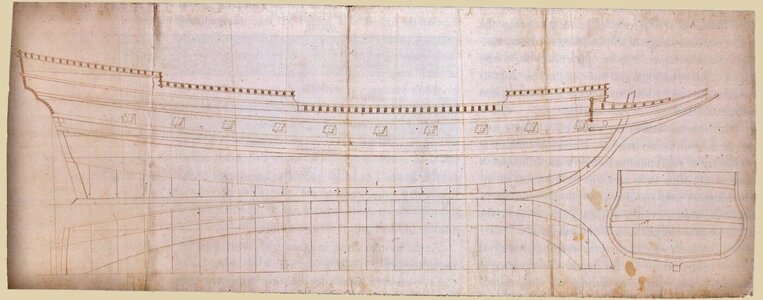

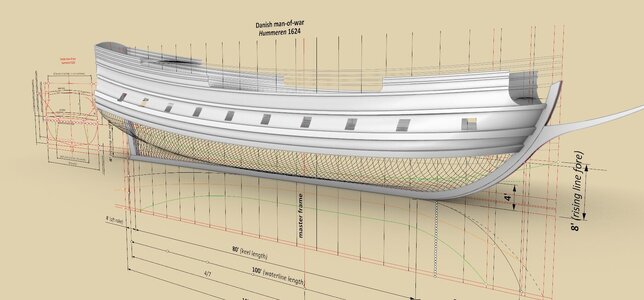

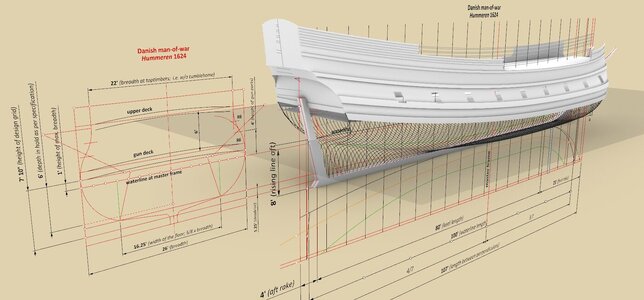

The very rich and valuable Danish archives contain a collection of technical ship designs from the very beginning of the 17th century, the equivalent of which is difficult to find elsewhere for such an early period. Among this group are also several designs attributed to David Balfour, a Scotsman in Danish service, and of particular interest from the point of view of this thread is the drawing denominated E9. This plan has been identified as the design for the warship Hummeren 1624, and several other vessels were built on its basis in a fairly short period of time, which in itself is the best indication of the good seagoing qualities of the vessel designed by Balfour.

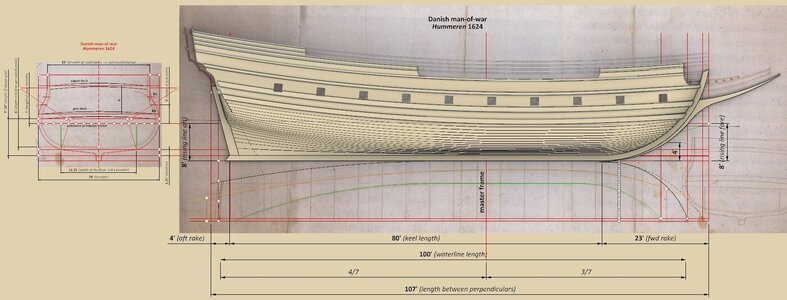

In a way, this plan is also complemented by the extant shipbuilding contracts for this ships' series. The dimensions specified in the specific contract for Hummeren 1624 (others may have had slightly modified dimensions) correspond perfectly with those measured on the plan. Thus:

Keel length: 80 feet

Rake forward: 23 feet

Rake aft: 4 feet

Rising line aft: 8 feet

Depth in hold (between ceiling and the lower edge of the main deck beams; the latter perfectly coincides with the level of max. breadth): 6 feet

Height of the gun deck: 6 feet

Breadth: 26 feet

Breadth of the transom: 15 ½ feet

Breadth at the gunwale: 22 feet

Dimensions were originally given in Danish alen equal to two feet; taken from the translation of the contract in David Balfour and early modern Danish Ship Design by Martin Bellamy, [in:] Mariner's Mirror 2006, vol. 92, no. 1.

The ship's crew is reported to have numbered 137 and the (main) artillery armament included 22 guns, almost certainly 18-pounders, as in other Danish vessels of similar size in this period.

* * *

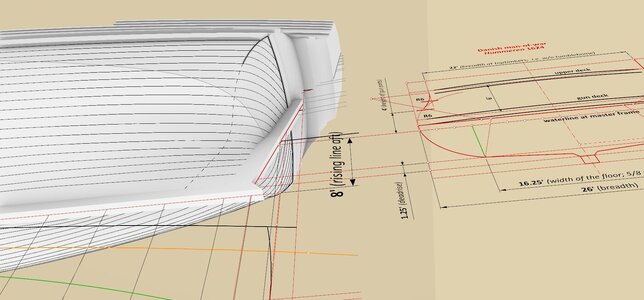

The plan of the prototype ship Hummeren 1624 is particularly interesting and important even for two reasons. Firstly, due to the very low draught required of the vessel, the designer decided not to use the more elaborate Mediterranean/English method, usually with as many as three sweeps for the underwater part of the hull (beside the hollowing/bottom curves), but instead opted for the much simpler North Continental/Dutch design method, and that too in its simplest form, with only one sweep (beside the surface of the „flat”).

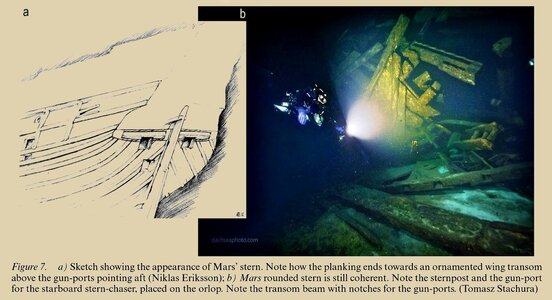

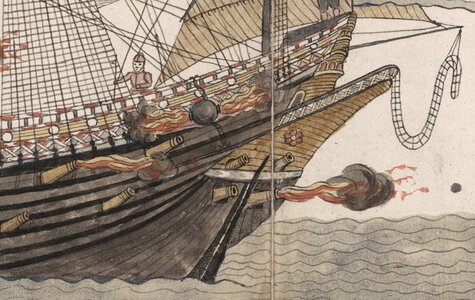

Apart from that, this is perhaps the earliest evidence of a technical-drawing nature for the introduction of the round tuck stern already in this period. Such other early cases are the plans of two vessels from the Hermitage collection in St Petersburg (Russia) and a sketch of a bend from the so-called Newton manuscript, however, these materials, it seems, can only be dated to a slightly later period – the second quarter of the 17th century.

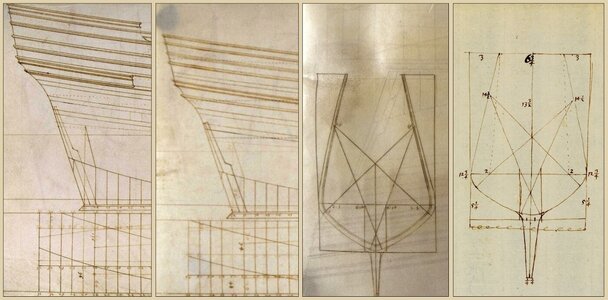

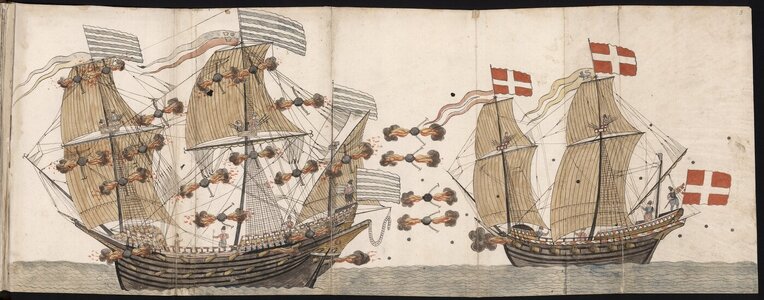

Below is a compilation of the relevant sections of the plans from the Hermitage and from Newton's manuscript. On the side views, first of all should be noted the characteristically tapered stern posts at the top (from the height of tuck) and the inclined lines running more or less parallel to the stern post, representing fashion pieces angled in this way, and on the last two reproductions the peculiar shape of the fashion pieces with an almost rectilinear run and a very small radius of lower breadth sweep, basically geometrically required for round tuck sterns. These are the features by which one can recognise what stern shape the designs below represent.

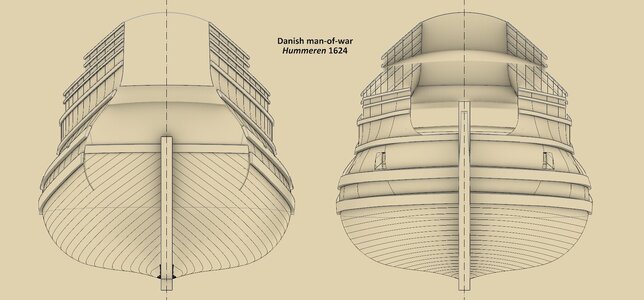

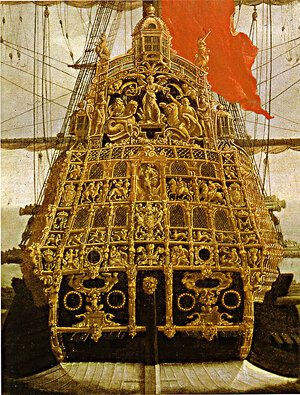

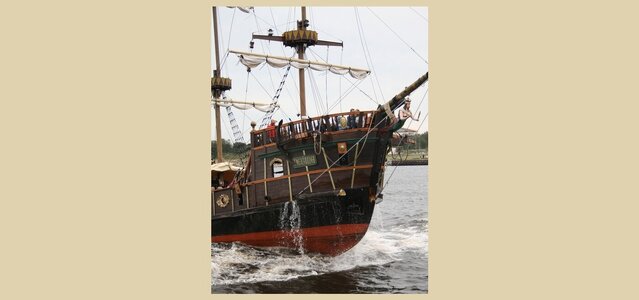

And, just for fun, some more renders with reconstructions of the warship Hummeren made from the original 1623 technical plan:

For interested, particularly relevant to this thematic specificity, both as a general reading and for some of detailed data, are the following works:

Niels M. Probst, Den Danske Flådes Historie 1588–1660. Christian 4.s flåde, Copenhagen 1996,

Ole Degn, Erik Gøbel, Dansk søfarts historie, 2. 1588–1720. Skuder og kompagner, Copenhagen 1997

Henrik Christiansen, Hans Christian Bjerg (ed.), Orlogsflådens skibe gennem 500 år. Den dansk-norske flåde 1510–1814 og den danske flåde 1814–2010, Copenhagen 2010,

Martin Bellamy, David Balfour and early modern Danish Ship Design, [in:] Mariner’s Mirror 2006, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 5–22,

Martin Bellamy, Christian IV and his Navy. A Political and Administrative History of the Danish Navy 1596–1648, Leiden 2006,

Christian P. P. Lemée, The Renaissance Shipwrecks from Christianshavn. An archaeological and architectural study of large carvel vessels in Danish waters, 1580–1640, Roskilde 2006.

.

Last edited: