.

Thank you again, gentlemen, for your entries.

* * *

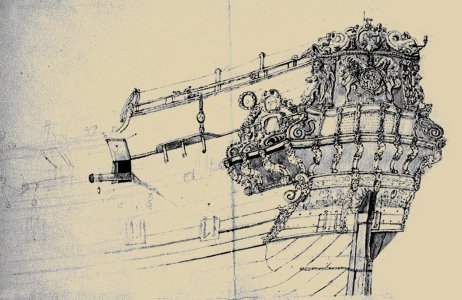

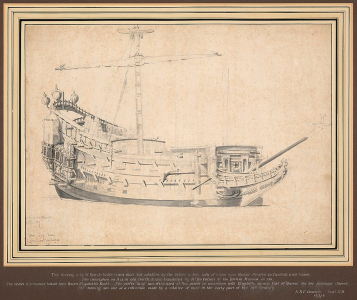

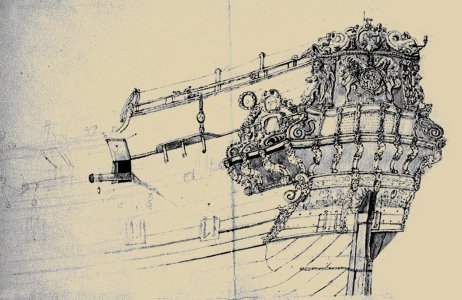

First, at Maarten's request, a reproduction of a graphic I found despite the still makeshift conditions, which depicts an English ship from the first half of the 17th century (British archives). If the museum description is to be believed – made most likely in 1648, and most likely depicting

Swallow 1634 (although it has suspiciously un-English style decoration).

Regardless of the identification, it is reasonable to think that this time the artist probably reproduced quite reliably the breaks in the strakes, just below the ends of the wing transom, as vividly reminiscent of those found on the Swedish ship

Bodekull 1659. It is true that there are not many such confirming examples of the transitional tuck form, nevertheless this period may have been quite short-lived, plus the artists may simply not have bothered with such insignificant and rather inconspicuous subtleties. After all, all the other butts of the planks that make up the strakes were usually not rendered by them either.

* * *

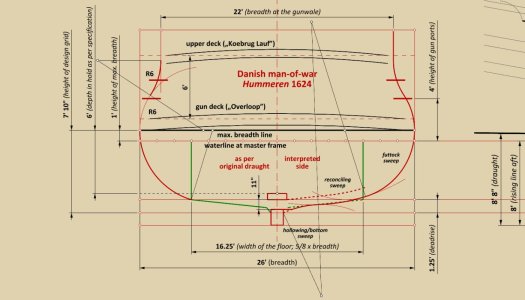

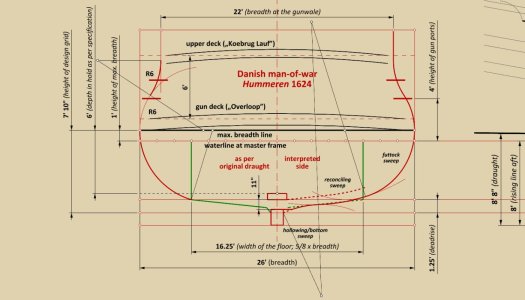

To buy some time (I'm still away from home, and have additionally decided to make apparently minor but labour-intensive adjustments to the first variant), for now, a slightly out-of-sequence proposal for interpreting the original master frame design of the

Hummeren 1624.

While it is true that the original master frame drawing can be taken quite literally as well, nevertheless, in my opinion, it rather captures the overall intention of the designer just in a quite conventional way, specifically:

– the use of only one (basic) sweep to shape the underwater section of the hull; given the low height allocated to this section (i.e. from deadrise level to maximum breadth level), the use of more sweeps would indeed be quite impractical and essentially unnecessarily cumbersome,

– together with the longitudinal projections determines the width of the ‘flat’ and its deadrise,

– finally, and very importantly, the garboard strake having a steep slope is a clear indication to the actual ship’s builder that the bottom of the ship should join the keel in the sharpest possible way, and this along the entire length of the hull.

In particular, adherence to the last-mentioned characteristic, due to the proportions and general shape of the hull, is of paramount importance in order to achieve at least satisfactory sailing properties of the designed ship, specifically its ability to keep to the wind. Otherwise, a broad ship with a shallow draft would have quite the character of a sail-powered raft, capable of moving basically only with the direction of the wind.

Also for exactly this purpose, the original design provides for a very large deadrise for a ship of this size and period. In these circumstances, the reconstruction should maximise both of these possibilities, as envisaged and given by Balfour, instead of rather haphazardly deforming the hull into a form of a bubble convex everywhere, as was unfortunately done in the

Hummeren–Project reconstruction project.

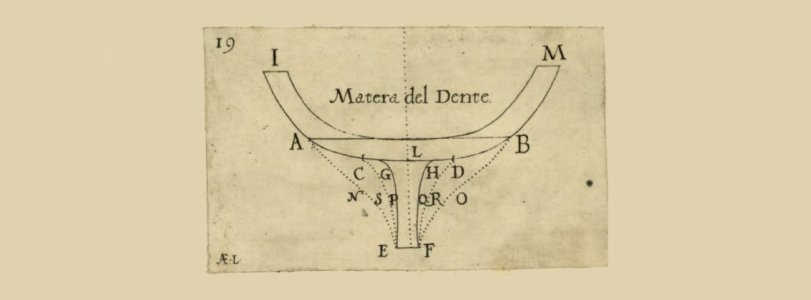

For the practical realisation of this purpose in the proposed interpretation, that is, to maintain at least an acceptable weatherliness of the ship, two suitable sweeps replace the bottom („flat”) line, marked here in green. It is worth recalling at this point that this ‘bottom line’, connecting the hull body proper to the keel assembly, was usually depicted on period plans (both in the Mediterranean and North Continental traditions) precisely in a simplified, conventional manner as a straight line to be replaced by other curves according to the proper, full-scale procedures used in shipyards.

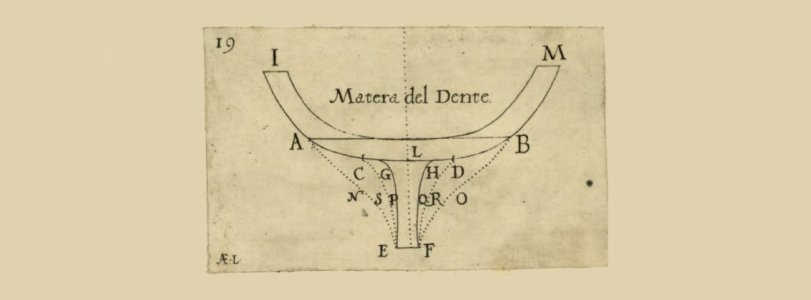

In the period, the issue of the shape of this particular section of the hull, and the resulting properties, is perhaps most extensively commented on by the Englishman Robert Dudley, a professional shipwright among others, in his work

Arcano del Mare, published in 1646, and which even merited an accompanying illustrative diagram, specifically made for this purpose (shown below). As an aside, it may also be added that Robert Dudley, still in the mid-17th century, described ship design exclusively in purely Mediterranean fashion.

In contrast, taking into account the general proportions of the hull, it is quite safe to assume, even before its mathematical evaluation, that the lateral stability will not only not be compromised in any way in this particular case, but may even turn out to be still too high in practice, which is also not quite beneficial for either the ship or the crew. In this light, the slight loss of volume of the submerged part of the hull (the value of which also affects the stability of the ship), resulting from the proposed interpretation, should at least not be the source of any problem.

.