.

Since existing publications, including academic ones, have actually been creating a Universe-sized research vacuum in the field of period ship design, particularly in the North Continental/Dutch tradition, for several decades now, it is worth taking a look at yet another design of Dutch origin, which I personally date to the late 17th and early 18th centuries and, according to design criteria, from an era before the widespread adoption of design diagonals, at least in the Netherlands.

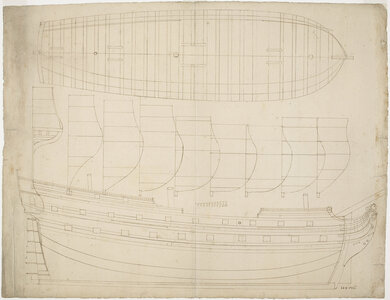

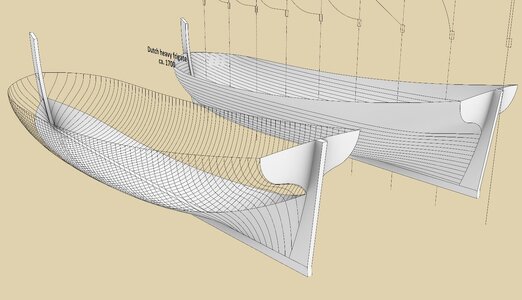

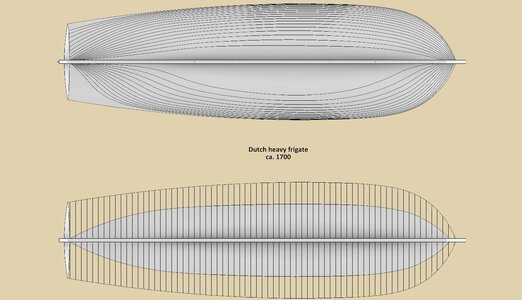

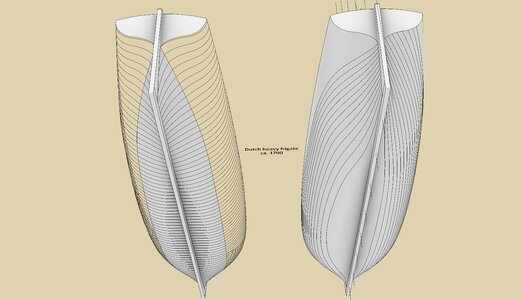

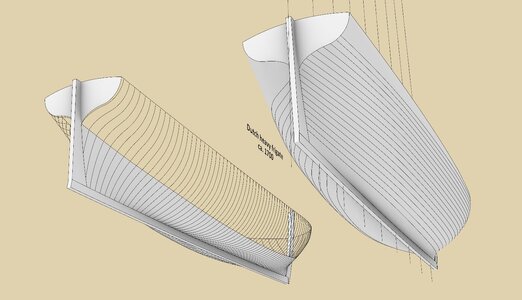

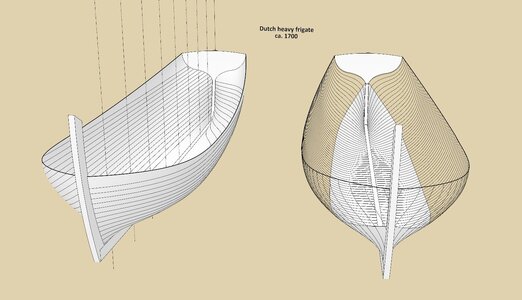

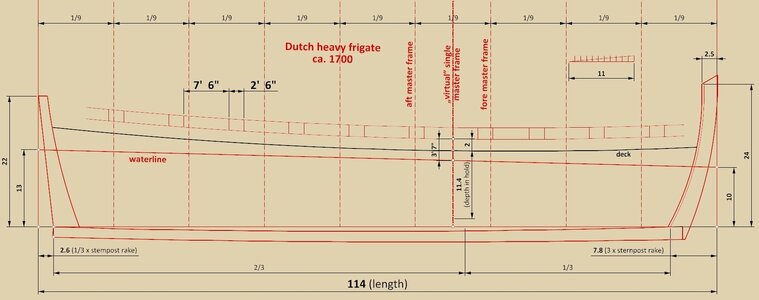

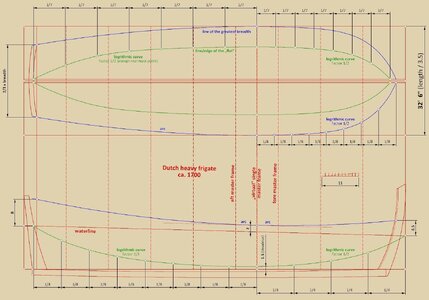

The design in question is that of a 114-foot-long heavy frigate, graphically designed for construction using the bottom-first method, as clearly evidenced by the two design lines characteristic of this method: the edge of the ‘flat’ and the ‘boeisel’ line, the latter separating the carpentry zones of bilges and sides of the ship's hull.

In the archival description, the drawing is dated 1780, which must be perceived as an obvious mistake. The square tuck stern, the short beakhead, the double wales, the double master frame (somewhat retrospectively here), as well as the (prediagonal) design method itself clearly point to the decades just around 1700, i.e. quite close to when van Yk's work on shipbuilding was published in 1697.

Link to archive and reproduction of the plan:

https://www.maritiemdigitaal.nl/index.cfm?event=search.getdetail&id=100199384

.