- Joined

- May 13, 2019

- Messages

- 72

- Points

- 113

Hi All,

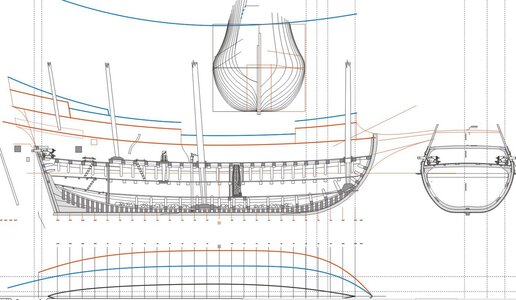

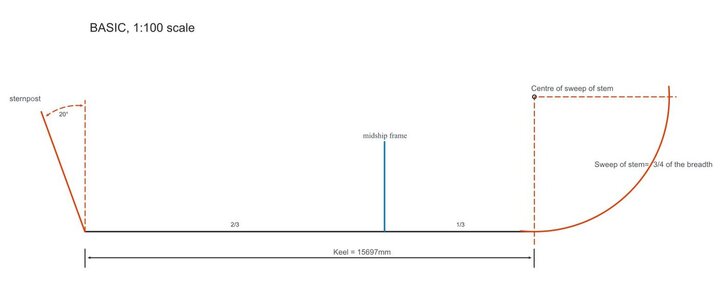

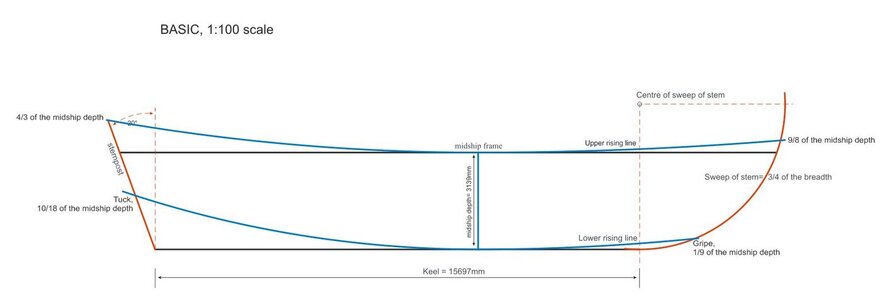

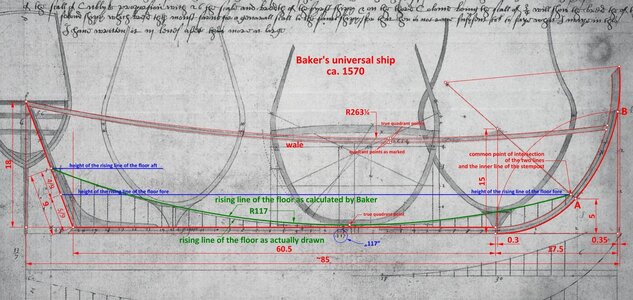

In this thread, I decided to try and create, step by step, the shape and construction of an English merchant ship circa 1600 - a sort of online anatomy of the ship. Why 1600? First, it is the turn of the century and the reign of the mighty Queen Elizabeth I, a time of economic boom, international expansion and English naval triumph. And second, in my view, it is also a time when the conservative period ends and a more progressive and flexible period in shipbuilding begins.

My project and future plan will be called

English merchant ship, ca. 1600.

I already have a few plans in my collection, and then I even tried to make a design of the Elizabeth Jonas, one of the biggest Tudor galleons, but realized I lacked neither experience nor knowledge. On searching for information I came across a book by Michael Oppenheim "A history of the administration of the Royal Navy and of merchant shipping in relation to the navy from 1509 to 1660", and some facts from this work interested me greatly, namely the merchant fleet, which played a major role in the rise of England and its prosperity of that period. Of particular interest to me were the tables on pages 174-175 and the document of 1582, which gives the following data: The number of ships of 100 tons or more is 177, there are also 70 ships of 80 to 100 tons and 1,383 ships of 20 to 80 tons. At this point, it should be mentioned, that so-called Levantine Company, initially gave its shareholders a profit of 300%! Which set the stage for my final decision on my next project, which will hopefully also be a springboard to a more complex project like the Elizabeth Jonas plan.

In this thread, I decided to try and create, step by step, the shape and construction of an English merchant ship circa 1600 - a sort of online anatomy of the ship. Why 1600? First, it is the turn of the century and the reign of the mighty Queen Elizabeth I, a time of economic boom, international expansion and English naval triumph. And second, in my view, it is also a time when the conservative period ends and a more progressive and flexible period in shipbuilding begins.

My project and future plan will be called

English merchant ship, ca. 1600.

I already have a few plans in my collection, and then I even tried to make a design of the Elizabeth Jonas, one of the biggest Tudor galleons, but realized I lacked neither experience nor knowledge. On searching for information I came across a book by Michael Oppenheim "A history of the administration of the Royal Navy and of merchant shipping in relation to the navy from 1509 to 1660", and some facts from this work interested me greatly, namely the merchant fleet, which played a major role in the rise of England and its prosperity of that period. Of particular interest to me were the tables on pages 174-175 and the document of 1582, which gives the following data: The number of ships of 100 tons or more is 177, there are also 70 ships of 80 to 100 tons and 1,383 ships of 20 to 80 tons. At this point, it should be mentioned, that so-called Levantine Company, initially gave its shareholders a profit of 300%! Which set the stage for my final decision on my next project, which will hopefully also be a springboard to a more complex project like the Elizabeth Jonas plan.