- Joined

- Dec 1, 2016

- Messages

- 6,398

- Points

- 728

before you start investing in tools i suggest you begin your scratch building odyssey with building a sem-kit. The major part of scratch building is in the building of the model. Either you will love it and want to do it again or you will get frustrated with it and take a step back.

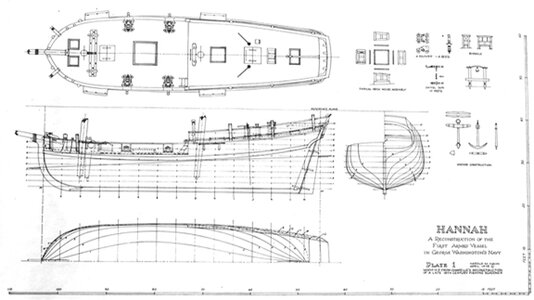

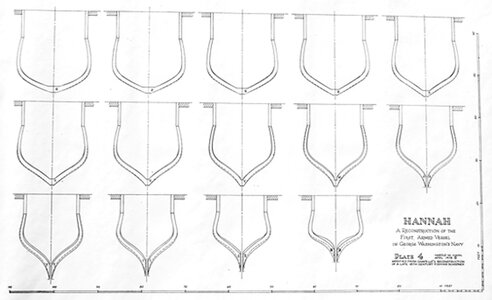

A model like Hahn's Hanna is a small uncompleted build which gives you an understanding of what to expect. At this point there is no need for all the tooling, the frames are laser cut, but don't let that fool you. The frames are cut oversize .040 so you have 1mm tolerance to work in from start to finish. building from semi-scratch has no instructions like a kit it is up to you to figure out the building process.

scratch building is like going from a build it out of the box kit to kit bashing to semi scratch to full blown scratch, adding tools and knowledge along the way.

A model like Hahn's Hanna is a small uncompleted build which gives you an understanding of what to expect. At this point there is no need for all the tooling, the frames are laser cut, but don't let that fool you. The frames are cut oversize .040 so you have 1mm tolerance to work in from start to finish. building from semi-scratch has no instructions like a kit it is up to you to figure out the building process.

scratch building is like going from a build it out of the box kit to kit bashing to semi scratch to full blown scratch, adding tools and knowledge along the way.