but that is not how the world of art works the status of the builder or artist makes a huge difference as a determining factor in how we judge its value

work by Andy Warhol may be a simple image of a soup can but it was done by Andy Warhol so it has a high value

Jackson Pollock may of just splashed paint on a canvas but you can not afford one of his paintings because of who did it

a model by Harold Hahn has a value of $50,000.00 because it is an original Hahn work.

each of the above are not the ultra best it is their name that gives it value. to the work

Dave, I get what you’re saying about name recognition playing a role in the art world, but I’m not sure that analogy fits squarely with what most of us are doing here or in the world of ship modeling. Comparing a Harold Hahn model to a Warhol painting feels like a leap, especially when most of us are building for personal fulfillment, historical interest, or craftsmanship, not auction houses or galleries. And no, I'm not the least bit ashamed to admit I wouldn't recognize a Warhol painting if it hit me over the head.

We’re not buying or selling models based on the “brand” of the builder, and I doubt many here are dropping $50,000 for the sake of a nameplate. Sure, provenance can add value, but in our community, most builders (whether hobbyists or pros) are admired for the

quality and

integrity of their work, not just who they are.

In 2019, Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan created

Comedian, a real banana duct-taped to a wall. Initially sold for $120,000 at Art Basel Miami Beach, an edition of this piece astonishingly sold for $6.2 million at Sotheby's in November 2024. The artwork includes a certificate of authenticity and installation instructions.

...or, do you want more such arts?

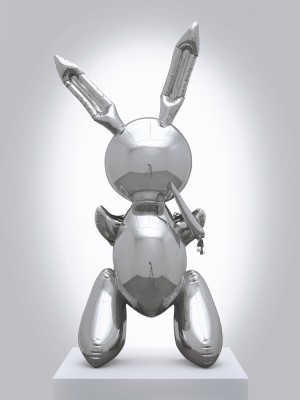

Jeff Koons' 1986 stainless steel sculpture

Rabbit, resembling a balloon animal, sold for $91.1 million in 2019, setting a record for the most expensive artwork sold by a living artist. Koons is known for transforming everyday objects into high-art sculptures.

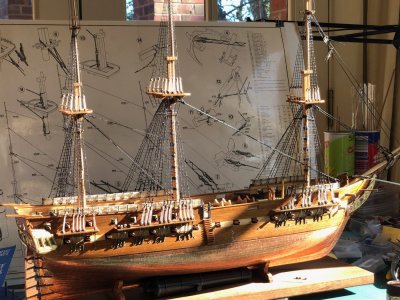

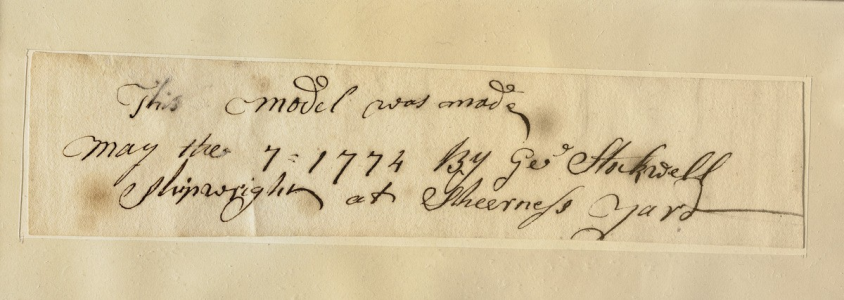

You may say those are not ship models. Here you go:

Märklin Oceanliner "Amerika" toy sells for $118,750, measures 38 inches in length

At the end of the day, ship modeling isn’t a performance art, it’s a craft rooted in research, dedication, and love of the subject. That’s where the true value lies, and that value should speak through the model itself, not just the signature next to it.