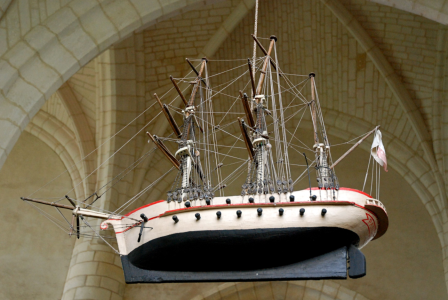

On of the first things an apprentice painter is taught is that a fine finish is 90% preparation and 10% application. Viewed up close as ship models are, a fine finish is one of the most essential features of a high-quality model and one most often overlooked by ship modelers. It is apparent that your hull is not

yet even close to being sufficiently sanded fair. As can be seen from the photo, the higher spots are sanded flat while the lower spots are still somewhat glossy. The entire hull must be perfectly smooth as a baby's bottom. Even when all the surface appears the same level, you should carefully run your fingertips over the surface to be sure of uniform smoothness. Your fingertips are a more reliable method of evaluating smoothness than your eyes are. Remember also that the reflective properties of any paint surface can be modified as may be desired by hand-rubbing with rottenstone and pumice powders, common traditional (and inexpensive) products available at paint and hardware stores. These abrasive powders can dull a glossy finish or even produce a beautiful soft glossy finish, depending upon how lony one rubs. Hand rubbing also removed any minute imperfections such as a speck of dust from the surface. A hand-rubbed finish can always be identified by running the fingertips over it. They look better than any premixed "flattened" or "matte" paint or "satin" varnish coating designed to imitate the true hand-rubbed finish. A hand-rubbed finish may be more effort than the average kit assembler may want to invest in their model, but it sure does make a model stand out. It's one of the distinguishing features of the amazing "builder's models" produced on either side of the turn of the 19th century into the first half of the 20th.

Even when one desires to portray a weathered, perhaps roughened, hull of an old, worn-out vessel, a correct appraisal of

scale viewing distance must be taken into account if the model is to create the effect of realism required of a high-quality scale model.

Scale viewing distance is simply "what does a thing look like when viewed from a given distance." If a miniature is to appear realistic, it must be made to appear as the full-size subject would appear if being viewed from its

full-scale distance. sIf the posts on ship modeling forums are any indication, ignorance of

scale viewing distance, or outright refusal to abide by its limitations because of one's ego, is one of the most frequently apparent errors seen. At most all scales below 1:12, plank seams, wooden plugs and trunnels, copper sheathing "rivets" (they are tacks,) and the like, are

invisible at scale viewing distances. Many modelers mistakenly show out of scale plank seams, plugs, trunnels, and other fasteners thinking they are "adding detail."

Out of scale detail is distraction that destroys the compelling impression of reality that defines a high-quality ship model. (And some ship model kit manufacturers have no hesitation including out of scale parts in their kits and claiming their model is "more detailed" than their competitors'!)

Scale viewing distance is easy to calculate by calculating the distance from the model viewer's eyes multiplied by the denominator of the model's scale. For example, if the model will be viewed by three feet away and the model's scale is 1:48, the

scale viewing distance is 144 feet (3 x 48 = 144). The detail on the model should be what one sees on the full-size ship when viewed from 148 feet away. If you're a modeler who expects your 1:48 model to be scrutinized from a foot away, then scale viewing distance is 48 feet.

Scale viewing distance applies not only to details, but also to color and gloss. As the viewing distance increases, glossy reflections

decrease. Glossy finishes on models are out of scale. Also, colors tend to darken, or take on a greyish cast, as viewing distance increases. No competent landscape painter will ever paint the hills in the distance the same color green as the meadow in the foreground. Modelers need to learn and apply these principles to the finishes of their models to avoid their looking like "toys." Studying landscape painting manuals will be helpful to learn this.

Modelers who haven't acquired the ability to intuitively recognize the scale viewing distance of ship models from their own experience of full-size ships, should experiment with other subjects. Create a full-size mock-up of the detail in question and view it from a measured distance. If you can see it, then portray on your model

exactly what you can see on your experimental subject,

not what the thing looks like when viewed up close! If you can't see it at full-scale,

don't model it at scale! Out of scale details just scream at the viewer, "It's a not a real ship!" which by any definition is the antithesis of what scale ship modeling is all about.

Considerations of scale viewing distance are particularly important when working with dioramas which impose the greatest demands for accurate detail on the modeler's skills. If you want your hull to look like a hull long laid up in ordinary without regular maintenance, you need to determine what such a hull will look like at its scale viewing distance. In most instances, the detailing, or "weathering" will be surprisingly subtle if it is done correctly. Exactly what that will actually look like will depend upon the research you do on similar surfaces viewed from a similar distance. Virtually

all ship's hulls will appear flat or "matte" finish at any scale viewing distance in 1:24 scale and below (A few "gold plater" yacht models will rise to an "eggshell" or "satin" finish at 1:24, though.) At most all scale viewing distances, most hulls will also appear perfectly smooth. Details like rivets and copper antifouling sheathing tacks can't be discerned by eye at half the length of a football field (at 1:48 scale) and certainly not at the full length of a football field (at 1:96 scale.) "Weathering" detail is added "on top" of the basic finishing job. It's really where the modeler's "artistry" comes into play. To pull it off, you have to add subtle "detail" in much the same fashion as an impressionist oil painter who uses slight variations of color washes to create the impression of distance for the viewer who's looking at the painting, or model, "up close."

Here are a couple of videos on landscape painting which address viewing distances greater than most model scale viewing distances, but nonetheless address the basic principles we have to apply in the context of ship modeling.