Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

3 December 1807 - HMS Curieux (18), John Sheriff (Killed in Action), engaged privateer Revanche (25) off Barbados.

HMS Curieux was a French corvette named

Curieux, launched in September 1800 at Saint-Malo to a design by François Pestel, and carrying sixteen 6-pounder guns. She was commissioned under

Capitaine de frégate Joseph-Marie-Emmanuel Cordier. The British captured her in 1804 in a cutting-out action at Martinique. In her five-year British career

Curieux captured several French privateers and engaged in two notable single-ship actions, also against privateers. In the first she captured

Dame Ernouf; in the second, she took heavy casualties in an indecisive action with

Revanche. In 1809

Curieux hit a rock; all her crew were saved but they had to set fire to her to prevent her recapture.

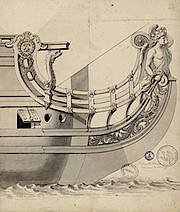

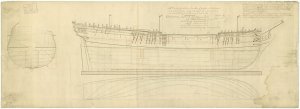

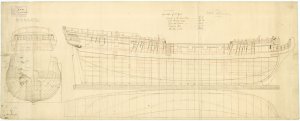

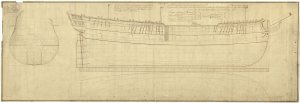

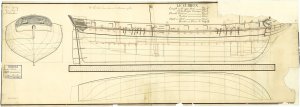

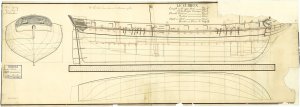

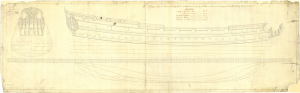

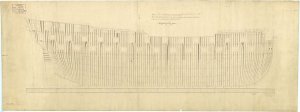

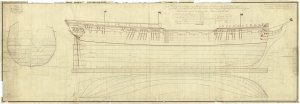

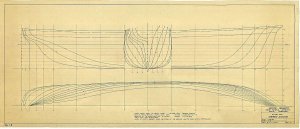

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name across the counter, the sheer lines with inboard detail and quarter gallery [figurehead missing], and longitudinal half-breadth for Curieux (captured 1804), a captured French Brig as taken off and fitted as an 18-gun Brig Sloop. The ship was at Plymouth to have defects made good between 17 July and 17 October 1805. Signed by Joseph Tucker [Master Shipwright, Plymouth Dockyard, 1802-1813]. The top right corner is missing, including the area around the figurehead.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name across the counter, the sheer lines with inboard detail and quarter gallery [figurehead missing], and longitudinal half-breadth for Curieux (captured 1804), a captured French Brig as taken off and fitted as an 18-gun Brig Sloop. The ship was at Plymouth to have defects made good between 17 July and 17 October 1805. Signed by Joseph Tucker [Master Shipwright, Plymouth Dockyard, 1802-1813]. The top right corner is missing, including the area around the figurehead.

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/84038.html#kmJh2aLdcsB68edb.99

Design

Curieux was a prototype, and the only vessel of her class. Construction on the subsequent

Curieux-class brigs started in 1803.

Type:

Corvette

Displacement: 290 tons (French)

Tons burthen: 329 5⁄94 (bm)

Length: 97 ft 0 in (29.57 m) (overall); 77 ft 3 in (23.55 m) (keel)

Beam: 28 ft 6 in (8.69 m)

Depth of hold: 13 ft 0 in (3.96 m)

Complement:

- French service: 94

- British service: 67

Armament:

- French service: 16 x 6-pounder guns

- British service: 8 x 6-pounder guns + 10 x 24-pounder carronades

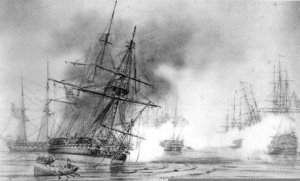

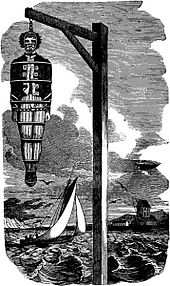

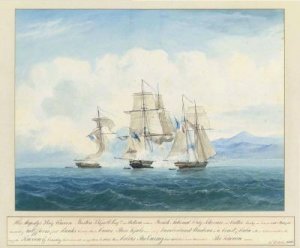

The French brig sloop ‘Curieux’ was fitted out at Martinique in order to attack British interests. As she was a threat to British West Indian commerce, the British Commodore Hood gave orders for her capture. Under the command of Lieutenant Robert Carthew Reynolds four boats with 60 seamen and 12 marines set out on a moonlit night from the British ship ‘Centaur’. This meant a 20-mile row to reach the ‘Curieux’ lying under the protection of the guns of Fort Edward. When Reynolds’s barge came in under the stern of the ‘Curieux’ he found that, providentially, a rope ladder hung down the side. He scaled it and cut a hole in the anti-boarding nets to enable his men to pour on board. Before she was taken the French lost nearly 40 killed and wounded. The British had nine wounded and Reynolds, who was one of them, subsequently died of his wounds. On the right side of the picture the ‘Curieux’ is shown just before her capture. Her anti-boarding netting is clearly visible. The sailors can be seen loosing her sails and cutting her cable, while the guns of Fort Edward are firing. A moon shines between her masts and in the left foreground another battery is in action. The painting is signed and dated ‘F. Sartoruis 1805’.

The French brig sloop ‘Curieux’ was fitted out at Martinique in order to attack British interests. As she was a threat to British West Indian commerce, the British Commodore Hood gave orders for her capture. Under the command of Lieutenant Robert Carthew Reynolds four boats with 60 seamen and 12 marines set out on a moonlit night from the British ship ‘Centaur’. This meant a 20-mile row to reach the ‘Curieux’ lying under the protection of the guns of Fort Edward. When Reynolds’s barge came in under the stern of the ‘Curieux’ he found that, providentially, a rope ladder hung down the side. He scaled it and cut a hole in the anti-boarding nets to enable his men to pour on board. Before she was taken the French lost nearly 40 killed and wounded. The British had nine wounded and Reynolds, who was one of them, subsequently died of his wounds. On the right side of the picture the ‘Curieux’ is shown just before her capture. Her anti-boarding netting is clearly visible. The sailors can be seen loosing her sails and cutting her cable, while the guns of Fort Edward are firing. A moon shines between her masts and in the left foreground another battery is in action. The painting is signed and dated ‘F. Sartoruis 1805’.

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/12029.html#hyYlUStZhiJyPXrc.99

Capture

On 4 February 1804, HMS

Centaur sent four boats and 72 men under Lieutenant Robert Carthew Reynolds to cut her out at Fort Royal harbour,

Martinique. The British suffered nine wounded, two of whom, including Reynolds, later died. The French suffered ten dead and 30 wounded, many mortally. Cordier, wounded, fell into a boat and escaped. The British sent

Curieux under a flag of truce to Fort Royal to hand the wounded over to their countrymen.

The

Royal Navy took her into service as HMS

Curieux, a

brig-sloop. Reynolds commissioned her but he had been severely wounded in the action and though he lingered for a while, died in September.

Reynold's successor was George Edmund Byron Bettesworth, who had been a lieutenant on

Centaur and part of the cutting out expedition.

Curieux's

first lieutenant was John George Boss who had been a midshipman on

Centaur and also in the cutting out expedition.

In June 1804,

Curieux recaptured the English brig

Albion, which was carrying a cargo of coal. Then, on 15 July, she captured the French privateer schooner

Elizabeth of six guns. That same day she captured the schooner

Betsey, which was sailing in ballast.

In September

Curieux recaptured the English brig

Princess Royal, which was carrying government stores. Then in January 1805

Curieux recaptured an American ship, from St. Domingo, that was carrying coffee. The American had been the prize of a French privateer.

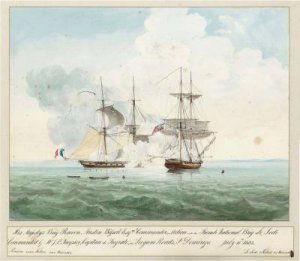

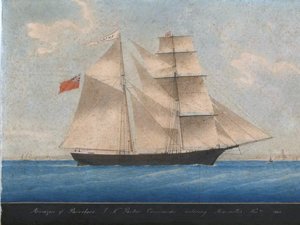

HMS 'Curieux' Captures 'Dame Ernouf', 8 February 1805, by Francis Sartorius Jr., National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

HMS 'Curieux' Captures 'Dame Ernouf', 8 February 1805, by Francis Sartorius Jr., National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Curieux and Dame Ernouf

Then on 8 February 1805,

Curieux chased the French privateer

Dame Ernouf (or

Madame Ernouf) for twelve hours before she able to bring her to action. After forty minutes of hard fighting

Dame Ernouf, which had a crew almost double in size relative to that of

Curieux, maneuvered to attempt a boarding. Bettesworth anticipated this and put his helm a-starboard, catching his opponent's

jib-boom so that he could rake the French vessel. Unable to fight back, the

Dame Ernouff struck. The action cost

Curieux five men killed and four wounded, including Bettesworth, who took a hit in his head from a musket ball.

Dame Ernouf had 30 men killed and 41 wounded. She carried 16 French long 6-pounder guns and had a crew of 120. This was the same armament as

Curieux carried, but in a smaller vessel. Bettesworth opined that she had fought so gallantly because her captain was also a part-owner. She was 20 days out of Guadeloupe and had taken one brig, which, however,

Nimrod had recaptured. The British took

Dame Ernouf into service as

Seaforth, but she capsized and foundered in a gale on 30 September 1805. There were only two survivors.

On 25 February

Curieux, under Bettesworth, captured a Spanish launch, name unknown, which she took into Tortola.

Lieutenant Boss was on leave at the time of the action but later took over as acting commander while Bettesworth recuperated. At Cumana Gut, Boss cut out several schooners and later took a brig from St. Eustatia.

Curieux and the schooner

Tobago cooperated in capturing two merchantmen lying for protection under the batteries at Barcelona, on the coast of Caraccas.

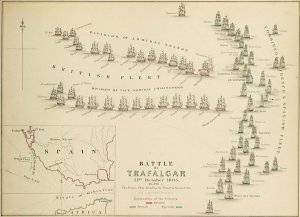

On 7 July,

Curieux arrived in Plymouth with dispatches from Lord Nelson. On her way, she had spotted Admiral Villeneuve's Franco-Spanish squadron on its way back to Europe from the West Indies and alerted the Admiralty. Rear-Admiral Sir Robert Calder, with 15 ships of the line, intercepted Villeneuve on 22 July, but the subsequent Battle of Cape Finisterre was indecisive, with the British capturing only two enemy ships.

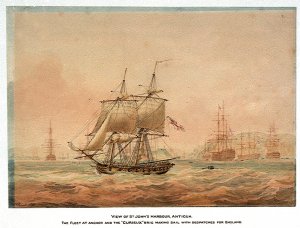

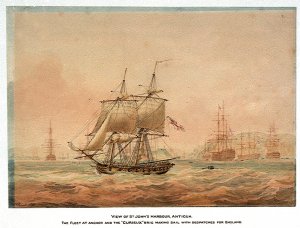

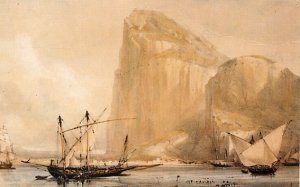

The last, but seventh in order of events, in series of ten drawings (PAF5871–PAF5874, PAF5876, PAF5880–PAF5881 and PAF5883–PAF5885) of mainly lesser-known incidents in Nelson's career, apparently intended for a set of engravings. Pocock's own description of this drawing in a letter of 9 July 1810 calls it 'a view of St Johns Harbour Antigua taken on the spot by myself with the Fleet at

The last, but seventh in order of events, in series of ten drawings (PAF5871–PAF5874, PAF5876, PAF5880–PAF5881 and PAF5883–PAF5885) of mainly lesser-known incidents in Nelson's career, apparently intended for a set of engravings. Pocock's own description of this drawing in a letter of 9 July 1810 calls it 'a view of St Johns Harbour Antigua taken on the spot by myself with the Fleet at  – the "Curieux" Brig (in the foreground) making sail with dispatches for England. Here though there is no fighting I thought the anxiety and promptitude of Lord Nelson wou'd be exemplified, and with a Correct View of Antigua wou'd give the Whole [set] a Variety.' Nelson's 'Victory' is in stern view to the right of 'Curieux', beyond the intervening rowing boat. Pocock's personal knowledge and drawing(s) of Antigua of course dated from his time as a Bristol sea captain, ending about 1778, not that of the incident shown. This was during the pre-Trafalgar chase to the West Indies, in early summer 1805, where Nelson failed to find Villeneuve's Franco-Spanish Fleet, which had already sailed again for Europe. On 12 June he sent home the 'Curieux' from Antigua with dispatches, to update the Admiralty, before his fleet pursued. By chance, 'Curieux' distantly sighted and overtook the enemy near the Azores, realized they were heading for Ferrol in north-western Spain, not Cadiz, and brought that vital news back to Lord Barham at the Admiralty, ahead of Nelson's return. For the rather complex circumstances of the commissioning of these ten drawings, and Pocock's related letters, see 'View of St Eustatius with the '"Boreas"' (PAF5871). Signed by the artist and dated in the lower left. Exhibited: NMM Pocock exhib. (1975), no. 52.

– the "Curieux" Brig (in the foreground) making sail with dispatches for England. Here though there is no fighting I thought the anxiety and promptitude of Lord Nelson wou'd be exemplified, and with a Correct View of Antigua wou'd give the Whole [set] a Variety.' Nelson's 'Victory' is in stern view to the right of 'Curieux', beyond the intervening rowing boat. Pocock's personal knowledge and drawing(s) of Antigua of course dated from his time as a Bristol sea captain, ending about 1778, not that of the incident shown. This was during the pre-Trafalgar chase to the West Indies, in early summer 1805, where Nelson failed to find Villeneuve's Franco-Spanish Fleet, which had already sailed again for Europe. On 12 June he sent home the 'Curieux' from Antigua with dispatches, to update the Admiralty, before his fleet pursued. By chance, 'Curieux' distantly sighted and overtook the enemy near the Azores, realized they were heading for Ferrol in north-western Spain, not Cadiz, and brought that vital news back to Lord Barham at the Admiralty, ahead of Nelson's return. For the rather complex circumstances of the commissioning of these ten drawings, and Pocock's related letters, see 'View of St Eustatius with the '"Boreas"' (PAF5871). Signed by the artist and dated in the lower left. Exhibited: NMM Pocock exhib. (1975), no. 52.

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/100711.html#yer2eas4oVlbFwEd.99

James Johnstone took command of

Curieux in July 1805. After refitting she sailed for the Lisbon station. On 25 November 1805

Curieux captured the Spanish privateer

Brilliano, under the command of Don Joseph Advis, some 13 leagues west of Cape Selleiro. She was a lugger of five carriage guns and a crew of 35 men.

Brilliano, which had been out five days from Port Carrel and two days before

Cureux captured her, had taken the English brig

Mary, sailing from Lynn to Lisbon with a cargo of coal.

Brilliano had also taken the brig

Nymphe, which had been sailing from Newfoundland with a cargo of fish for Viana. The next day

Curieux apparently captured

San Josef el Brilliant.

On 5 February 1806, two years after her own capture,

Curieux captured the 6-gun privateer

Baltidore (alias

Fenix) and her crew of 47 men. The capture occurred 27 leagues west of Lisbon after a chase of four hours.

Baltidore had been out of Ferrol one month, during which time she had captured

Good Intent, which had been sailing from Lisbon for London. About a month earlier, on 3 January,

Mercury had recaptured

Good Intent, which had been part of a convoy that

Mercury had been escorting from

Newfoundland to Portugal.

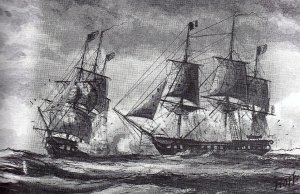

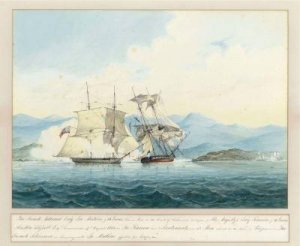

Curieux and Revanche

In March 1806 John Sheriff took over as captain of

Curieux. On 3 December 1807, off Barbados,

Curieux, now armed with eight 6-pounders and ten 18-pounder carronades, engaged the 25-gun privateer

Revanche, commanded by Captain Vidal.

Revanche, which had been the slaver

British Tar, was the more heavily armed (chiefly English 9-pounders, and one long French 18-pounder upon a traversing carriage on the forecastle) and had a crew of 200 men.

Revanche nearly disabled

Curieux, while killing Sheriff. Lieutenant Thomas Muir wanted to board

Revanche, but too few crewmen were willing to follow him. The two vessels broke off the action and

Revanche escaped.

Curieux, whose shrouds and back-stays were shot away, and whose two topmasts and jib-boom had been damaged, was unable to pursue.

In addition to the loss of her captain,

Curieux had suffered another seven dead and 14 wounded.

Revanche, according to a paragraph in the

Moniteur, lost two men killed and 13 wounded.

Curieux, as soon as her crew had partially repaired her, made sail and anchored the next day in Carlisle Bay, Barbados. A subsequent court martial into why Muir had not taken or destroyed the enemy vessel mildly rebuked Muir for not having hove-to repair his vessel's damage once it became obvious that

Curieux was in no condition to overtake

Revanche.

Further service

In February 1808 Commander Thomas Tucker assumed command, to be succeeded by Commander Andrew Hodge. Lieutenant the Honourable Henry George Moysey, possibly acting, then took command. Under his command

Curieux was engaged in the blockade of Guadaloupe, where she cut out a privateer from St. Anne's Bay, Jamaica.

On 18 February 1809,

Latona captured the French frigate

Felicité.

Curieux shared in the prize money, together with all the other vessels that been associated in the blockade of the Saintes.

Loss

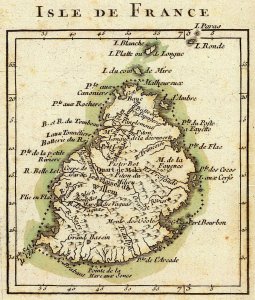

On 22 September 1809, at about 3:30am,

Curieux struck a rock off Petit-Terre off the

Îles des Saintes. The rock was 30 yards from the beach in 11 feet of water. At first light,

Hazard came to her assistance and her guns and stores were removed.

Hazard then winched

Curieux off a quarter of a cable but she slipped back and ran directly onto the reef. There she bilged. All her crew was saved but the British burned her to prevent her recapture. A court martial board found Lieutenant John Felton, the officer of the watch, guilty of negligence and dismissed him from the service. Moysey died the next month of yellow fever.

Post script

On 30 August 1860, the Prince of Wales was visiting Sherbrooke, where he met John Felton, who had emigrated to Canada after being dismissed the service. The Prince of Wales exercised his royal prerogative and restored Felton to his erstwhile rank in the Navy.

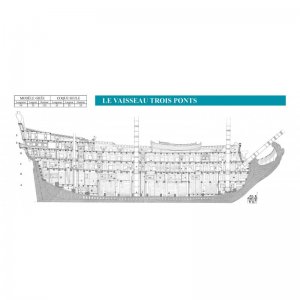

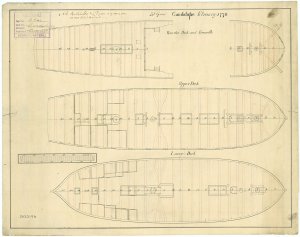

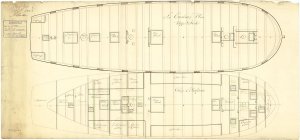

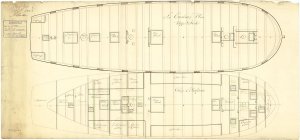

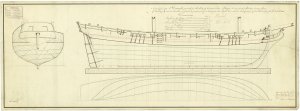

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the upper deck and lower deck with platforms for Curieux (captured 1804), a captured French Brig as taken off and fitted as an 18-gun Brig Sloop. The ship was at Plymouth to have defects made good between 17 July and 17 October 1805. Signed by Joseph Tucker [Master Shipwright, Plymouth Dockyard, 1802-1813].

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the upper deck and lower deck with platforms for Curieux (captured 1804), a captured French Brig as taken off and fitted as an 18-gun Brig Sloop. The ship was at Plymouth to have defects made good between 17 July and 17 October 1805. Signed by Joseph Tucker [Master Shipwright, Plymouth Dockyard, 1802-1813].

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/84039.html#A2U1SvE7cuSX9sXj.99

British Tar was built in 1797 in Plymouth (probably Plymouth, Massachusetts). She never enters

Lloyd's Register under that name, suggesting that she may have been an American vessel that only came to Bristol, and was renamed, shortly before she sailed from Bristol in 1805. In 1805 she made a slave trading voyage during which the French captured her. She became the privateer

Revanche, out of Guadeloupe.

Revanche fought an inconclusive

single-ship action in 1806 with HMS

Curieux. The British captured

Revanche in 1808.

Tons burthen: 230, or 232 (bm)

Complement:

- 1805: 30, or 35

- 1807: 200

- 1808: 44

Armament:

- 1805:12 × 6-pounder guns

- 1807:1 × 12-pounder + 6 × 4-pounder guns

- 1808:6 × 12-pounder guns

Slaver

British Tar appears in the Bristol Presentments for 1805 and 1806, but not before or later. Captain James Gordon received a letter of marque on 14 November 1805.

British Tar, Gordon, master, sailed from England on 30 December 1805, bound for West Africa. She was reported "well" in the River Gambia on 13 May 1806 and was expected to leave in a few days. A second report has her "all well" at Goree on 26 July, and expected to sail for the West Indies on 26 July. However, the next report has a privateer of ten guns and 70 men capturing

British Tar, of Bristol, on 18 July and taking her into Guadeloupe.

She had gathered 279 slaves from Gambia and

Goree and her captors landed 310, for a loss rate of 10%.

French privateer Revanche

The French commissioned

British Tar as the privateer

Revanche in Guadeloupe in September 1807 under Captain Alexis Grassin. She made a second cruise between November 1807 and January 1808 under Captain Vidal.

On 3 December 1807

Revanche encountered HMS

Curieux. Rather than fleeing,

Revanche, which was more heavily armed than

Curieux (British records) or less heavily armed (French records) decided to give battle. The ensuing engagement was sanguinary but inconclusive.

Revanche suffered two men killed and 13 wounded;

Curieux seven killed and 14 wounded.

Fate

Revanche made a third cruise in 1808. On 5 December 1808 HMS

Belette captured

Revanche, of six 12-pounder guns and 44 men, and described as a letter of marque brig.

Revanche was taking provisions from Bordeaux to Guadeloupe when she encountered

Belette. Captain Sanders described

Revanche as having been "a very successful Privateer all this War, and was intended for a Cruizer in those Seas.

Belette sent

Revanche into Antigua.

British Tar was still listed in

Lloyd's Register and the

Register of Shipping until at least 1812, but with long stale data.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Curieux_(1804)

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!csearch;searchTerm=Curieux

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Tar_(1797_ship)

– the "Curieux" Brig (in the foreground) making sail with dispatches for England. Here though there is no fighting I thought the anxiety and promptitude of Lord Nelson wou'd be exemplified, and with a Correct View of Antigua wou'd give the Whole [set] a Variety.' Nelson's 'Victory' is in stern view to the right of 'Curieux', beyond the intervening rowing boat. Pocock's personal knowledge and drawing(s) of Antigua of course dated from his time as a Bristol sea captain, ending about 1778, not that of the incident shown. This was during the pre-Trafalgar chase to the West Indies, in early summer 1805, where Nelson failed to find Villeneuve's Franco-Spanish Fleet, which had already sailed again for Europe. On 12 June he sent home the 'Curieux' from Antigua with dispatches, to update the Admiralty, before his fleet pursued. By chance, 'Curieux' distantly sighted and overtook the enemy near the Azores, realized they were heading for Ferrol in north-western Spain, not Cadiz, and brought that vital news back to Lord Barham at the Admiralty, ahead of Nelson's return. For the rather complex circumstances of the commissioning of these ten drawings, and Pocock's related letters, see 'View of St Eustatius with the '"Boreas"' (PAF5871). Signed by the artist and dated in the lower left. Exhibited: NMM Pocock exhib. (1975), no. 52.

– the "Curieux" Brig (in the foreground) making sail with dispatches for England. Here though there is no fighting I thought the anxiety and promptitude of Lord Nelson wou'd be exemplified, and with a Correct View of Antigua wou'd give the Whole [set] a Variety.' Nelson's 'Victory' is in stern view to the right of 'Curieux', beyond the intervening rowing boat. Pocock's personal knowledge and drawing(s) of Antigua of course dated from his time as a Bristol sea captain, ending about 1778, not that of the incident shown. This was during the pre-Trafalgar chase to the West Indies, in early summer 1805, where Nelson failed to find Villeneuve's Franco-Spanish Fleet, which had already sailed again for Europe. On 12 June he sent home the 'Curieux' from Antigua with dispatches, to update the Admiralty, before his fleet pursued. By chance, 'Curieux' distantly sighted and overtook the enemy near the Azores, realized they were heading for Ferrol in north-western Spain, not Cadiz, and brought that vital news back to Lord Barham at the Admiralty, ahead of Nelson's return. For the rather complex circumstances of the commissioning of these ten drawings, and Pocock's related letters, see 'View of St Eustatius with the '"Boreas"' (PAF5871). Signed by the artist and dated in the lower left. Exhibited: NMM Pocock exhib. (1975), no. 52.

, Virginia

, Virginia

haven. Sultan's boats, and those of Shamrock, were able to rescue the crew and all the troops, save five men. The troops consisted of 200 men from the 40th Regiment of Foot.

haven. Sultan's boats, and those of Shamrock, were able to rescue the crew and all the troops, save five men. The troops consisted of 200 men from the 40th Regiment of Foot.