Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

28 November 1944 - 10 days after commissioning Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano sunk by submarine USS Archerfish

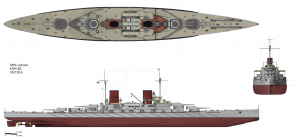

Shinano (信濃), was an

aircraft carrier built by the

Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during

World War II, the largest such built up to that time.

Laid down in May 1940 as the third of the

Yamato-class battleships,

Shinano's partially complete hull was ordered to be converted to a carrier following Japan's disastrous loss of four

fleet carriers at the

Battle of Midway in mid-1942. Her conversion was still not finished in November 1944 when she was ordered to sail from the

Yokosuka Naval Arsenal to

Kure Naval Base to complete

fitting out and transfer a load of 50

Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka rocket-propelled

kamikaze flying bombs. Hastily dispatched, she had an inexperienced crew and serious design and construction flaws, lacked adequate pumps and

fire-control systems, and did not carry a single aircraft. She was sunk en route, 10 days after

commissioning, on 29 November 1944, by four

torpedoes from the

U.S. Navy submarine Archerfish. Over a thousand sailors and civilians were rescued and 1,435 were lost, including her captain. She remains the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.

Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano underway during her sea trials.

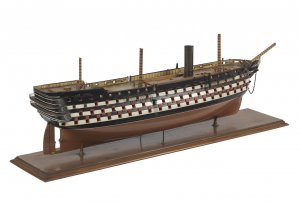

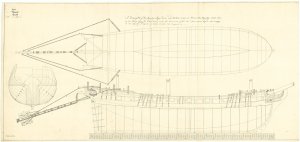

Design and description

One of two additional

Yamato-class

battleships ordered as part of the 4th Naval Armaments Supplement Program of 1939,

Shinano was named after the old province of Shinano, following the Japanese ship-naming conventions for battleships. She was laid down on 4 May 1940 at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal to a modified

Yamato-class design: her armor would be 10–20 millimeters (0.39–0.79 in) thinner than that of the earlier ships, as it had proved to be thicker than it needed to be for the desired level of protection, and her heavy

anti-aircraft (AA) guns would be the new 65-

caliber 10 cm Type 98 dual-purpose gun, as it had superior ballistic characteristics and a higher rate of fire than the 40-caliber 12.7 cm Type 89 guns used by her

half-sisters.

Construction and conversion

As with

Shinano's half-sisters

Yamato and

Musashi, the new ship's existence was kept a closely guarded secret. A tall fence was erected on three sides of the

graving dock, and those working on the conversion were confined to the yard compound. Serious punishment—up to and including death—awaited any worker who mentioned the new ship. As a result,

Shinano was the only major warship built in the 20th century to have avoided being officially photographed during its construction. The ship is only known to have been photographed twice: on 1 November 1944, by a Boeing B-29 Superfortress

reconnaissance aircraft from an altitude of 9,800 meters (32,000 ft), and ten days later, by a civilian photographer aboard a harbor

tug during

Shinano's initial sea trials in

Tokyo Bay.

In December 1941, construction on

Shinano's hull was temporarily suspended to allow the IJN time to decide what to do with the ship. She was not expected to be completed until 1945, and the sinking of the British capital ships

Prince of Wales and

Repulse by IJN bombers had called into question the viability of battleships in the war. The navy also wanted to make the large drydock in which the ship was being built available, which required either

scrapping the portion already completed or finishing it enough to

launch it and clear the drydock. The IJN decided on the latter, albeit with a reduced work force which was expected to be able to launch the ship in one year.

In the month following the disastrous loss of four

fleet carriers at the June 1942 Battle of Midway, the IJN ordered the ship's unfinished hull converted into an aircraft carrier. Her hull was only 45 percent complete by that time, with structural work complete up to the lower deck and most of her machinery installed. The main deck, lower side armor, and upper side armor around the ship's

magazines had been completely installed, and the forward barbettes for the main guns were also nearly finished. The navy decided that

Shinano would become a heavily armored support carrier—carrying reserve aircraft, fuel and ordnance in support of other carriers—rather than a fleet carrier.

As completed,

Shinano had a length of 265.8 meters (872 ft 1 in) overall, a beam of 36.3 meters (119 ft 1 in) and a draft of 10.3 meters (33 ft 10 in). She displaced 65,800 metric tons (64,800 long tons) at

standard load, 69,151 metric tons (68,059 long tons) at normal load and 73,000 metric tons (72,000 long tons) at full load.

Shinano was the heaviest aircraft carrier yet built, a record she held until the 81,000-metric-ton (80,000-long-ton) USS

Forrestal was launched in 1954. She was designed for a crew of 2,400 officers and enlisted men.

Commissioning and sinking

Commissioning and sinking

Departure from Yokosuka

On 19 November 1944,

Shinano was formally commissioned at Yokosuka, having spent the previous two weeks

fitting out and performing sea trials. Worried about her safety after a U.S. reconnaissance bomber fly-over, the Navy General Staff ordered

Shinano to depart for Kure by no later than 28 November, where the remainder of her fitting-out would take place. Abe asked for a delay in the sailing date as the majority of her watertight doors had yet to be installed, the compartment air tests had not been conducted, and many holes in the compartment bulkheads for electrical cables, ventilation ducts and pipes had not been sealed. Importantly, fire mains and bailing systems lacked pumps and were inoperable; even though most of the crew had sea-going experience, they lacked training in the portable pumps on board. The escorting destroyers,

Isokaze,

Yukikaze and

Hamakaze, had just returned from the Battle of Leyte Gulf and required more than three days to conduct repairs and to allow their crews to recuperate.

Abe's request was denied, and

Shinano departed as scheduled with the escorting destroyers at 18:00 on 28 November. Abe commanded a crew of 2,175 officers and men. Also on board were 300 shipyard workers and 40 civilian employees. Watertight doors and hatches were left open for ease of access to machinery spaces, as were some manholes in the double and triple-bottomed hull. Abe preferred a daylight passage, since it would have allowed him extra time to train his crew and given the destroyer crews time to rest. However, he was forced to make a nighttime run when he learned the Navy General Staff could not provide air support.

Shinano carried six

Shinyo suicide boats, and 50

Ohka suicide flying bombs; her other aircraft were not planned to come aboard until later. Her orders were to go to Kure, where she would complete fitting out and then deliver the

kamikaze craft to the Philippines and Okinawa. Traveling at an average speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), she needed sixteen hours to cover the 300 miles (480 km) to Kure. As a measure of how important

Shinano was to the naval command, Abe was slated for promotion to

rear admiral once its fitting out was complete.

Attacked

Archerfish

Archerfish on the surface, June 1945

At 20:48, the American submarine

Archerfish, commanded by Commander Joseph F. Enright, picked up

Shinano and her escorts on her radar and pursued them on a parallel course. Over an hour and a half earlier,

Shinano had detected the submarine's radar. Normally,

Shinano would have been able to outrun

Archerfish, but the zig-zagging movement of the carrier and her escorts—intended to evade any American subs in the area—inadvertently turned the task group back into the sub's path on several occasions. At 22:45, the carrier's lookouts spotted

Archerfish on the surface and

Isokaze broke formation, against orders, to investigate. Abe ordered the destroyer to return to the formation without attacking because he believed that the submarine was part of an American wolfpack. He assumed

Archerfish was being used as a decoy to lure away one of the escorts to allow the rest of the pack a clear shot at

Shinano. He ordered his ships to turn away from the submarine with the expectation of outrunning it, counting on his 2-knot (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph) margin of speed over the submarine. Around 23:22, the carrier was forced to reduce speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), the same speed as

Archerfish, to prevent damage to the propeller shaft when a

bearing overheated. At 02:56 on 29 November,

Shinano turned to the southwest and headed straight for

Archerfish. Eight minutes later,

Archerfish turned east and submerged in preparation to attack. Enright ordered his torpedoes set for a depth of 10 feet (3.0 m) in case they ran deeper than set; he also intended to increase the chances of

capsizing the ship by punching holes higher up in the hull. A few minutes later,

Shinano turned south, exposing her entire side to

Archerfish—a nearly ideal firing situation for a submarine. The escorting destroyer on that side passed right over

Archerfish without detecting her. At 03:15

Archerfish fired six torpedoes before diving to 400 feet (121.9 m) to escape a depth charge attack from the escorts.

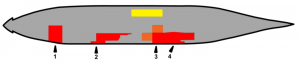

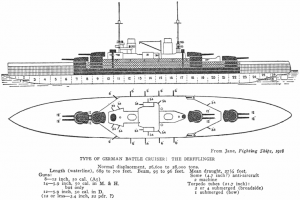

Four torpedoes struck

Shinano, at an average depth of 4.27 meters (14 ft 0 in). The first hit towards the stern, flooding refrigerated storage compartments and one of the empty aviation gasoline storage tanks, and killing many of the sleeping engineering personnel in the compartments above. The second hit the compartment where the starboard outboard propeller shaft entered the hull and flooded the outboard

engine room. The third hit further forward, flooding the No. 3 boiler room and killing every man on watch. Structural failures caused the two adjacent boiler rooms to flood as well. The fourth flooded the starboard air compressor room, adjacent anti-aircraft gun magazines, and the No. 2

damage-control station, and ruptured the adjacent oil tank.

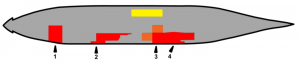

Sinking

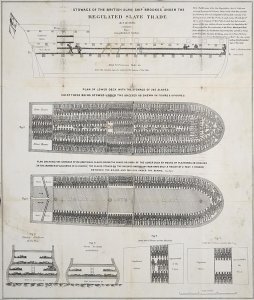

Diagram showing locations of torpedo hits and ensuing flooding: Red shows compartments immediately flooded, orange slowly flooded, and yellow deliberate flooding to offset the ship's list

Though severe, the damage to

Shinano was at first judged to be manageable. The crew were confident in the ship's armor and strength, which translated into lax initial efforts to save the ship. This overconfidence extended to Abe. He doubted the sub's torpedoes could inflict serious damage, since he was well aware that American torpedoes were inferior to Japanese torpedoes in both potency and accuracy. He ordered the carrier to maintain its maximum speed even after the last torpedo hit. This pushed more water through the holes in the hull resulting in extensive flooding. Within a few minutes she was

listing 10 degrees to starboard. Despite the crew pumping 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) of water into the port

bilges, the list increased to 13 degrees. When it became apparent the damage was more severe than first thought, Abe ordered a change of course towards Shiono Point. Progressively increasing flooding increased the list to 15 degrees by 03:30. Fifty minutes later, Abe ordered the empty port outboard tanks to be counter-flooded, reducing the list to 12 degrees for a brief time. After 05:00 he ordered the civilian workers to be transferred to the escorts as they were impeding the crew in their duties.

A half-hour later,

Shinano was making 10 knots with a 13 degree list. At 06:00 her list had increased to 20 degrees after the starboard boiler room flooded, at which point the valves of the port trimming tanks rose above the waterline and became ineffective. The engines shut down for lack of steam around 07:00, and Abe ordered all of the propulsion compartments evacuated an hour later. He then ordered the three outboard port boiler rooms flooded in a futile attempt to reduce the carrier's list. He also ordered

Hamakaze and

Isokaze to take her in tow. However, the two destroyers only displaced 5,000 metric tons (4,900 long tons) between them, about one-fourteenth of

Shinano's displacement and not nearly enough to overcome her deadweight. The first tow cables snapped under the strain and the second attempt was aborted for fear of injury to the crews if they snapped again. The ship lost all power around 09:00 and was now listing over 20 degrees. At 10:18, Abe gave the order to abandon ship; by this time

Shinano had a list of 30 degrees. As she heeled, water flowed into the open elevator well on her flight deck, sucking many swimming sailors back into the ship as she sank. A large exhaust vent below the flight deck also sucked many other sailors into the ship as she submerged.

At 10:57

Shinano finally capsized and sank stern-first at coordinates (32°07′N 137°04′ECoordinates:

32°07′N 137°04′E), 65 miles (105 km) from the nearest land, in approximately 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) of water,

taking 1,435 officers, men and civilians to their deaths. The dead included Abe and both of his navigators, who chose to go down with the ship. Rescued were 55 officers and 993 petty officers and enlisted men, plus 32 civilians for a total of 1,080 survivors. After their rescue, the survivors were isolated on the island of Mitsuko-jima until January 1945 to suppress the news of the carrier's loss. The carrier was formally struck from the Naval Register on 31 August.

US Naval Intelligence did not initially believe Enright's claim to have sunk a carrier.

Shinano's construction had not been detected through

decoded radio messages or other means, and the American analysts believed that they had located all of Japan's surviving carriers. Enright was eventually credited with sinking a 28,000-long-ton (28,000 t)

Hayatake (

Hiyō-class) carrier by the acting commander of the Pacific Fleet's submarine force on the basis of a drawing Enright submitted depicting the ship he had attacked. The Americans only learned about the existence of

Shinano after the war; following this discovery Enright was credited with her sinking and awarded the

Navy Cross.

Post-war analysis of the sinking

Post-war analysis by the U.S. Naval Technical Mission to Japan noted that

Shinano had serious design flaws. Specifically, the joint between the waterline armor belt on the upper hull and the anti-torpedo bulge on the underwater portion was poorly designed, a trait shared by the

Yamato-class battleships;

Archerfish's torpedoes all exploded along this joint. The force of the torpedo explosions also dislodged an

I-beam in one of the boiler rooms, which punched a hole into another boiler room. In addition, the failure to test for water-tightness in each compartment played a role as potential leaks could not be found and patched before

Shinano put to sea. The executive officer blamed the large amount of water that entered the ship on the failure to air-test the compartments for leaks. He reported hearing air rushing through gaps in the water-tight doors just minutes after the last torpedo hit—a sign that seawater was rapidly entering the ship, proving the doors were unseaworthy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_aircraft_carrier_Shinano

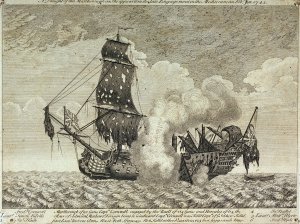

of Captain Jan de Haes. Blake received little support from the remainder of the English fleet. When the Happy Entrance entered the channel, she was at once assaulted and only with difficulty managed to extract herself. The other English ships began to understand the tactical situation: the exit functioned as a bottle neck and trying to force it would only allow the Dutch to overpower the English ships one by one. On the other hand, most Dutch ships did not engage either. Annoyed, Commodore

of Captain Jan de Haes. Blake received little support from the remainder of the English fleet. When the Happy Entrance entered the channel, she was at once assaulted and only with difficulty managed to extract herself. The other English ships began to understand the tactical situation: the exit functioned as a bottle neck and trying to force it would only allow the Dutch to overpower the English ships one by one. On the other hand, most Dutch ships did not engage either. Annoyed, Commodore

, Pluto prepared for action and when the two vessels passed each other, they exchanged broadsides. Duc de Chartres turned and gave chase, catching up with her quarry. Unable to escape, and outgunned, Pluto

, Pluto prepared for action and when the two vessels passed each other, they exchanged broadsides. Duc de Chartres turned and gave chase, catching up with her quarry. Unable to escape, and outgunned, Pluto