Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

Other Events on 24 November

1642 – Abel Tasman becomes the first European to discover the island Van Diemen's Land (later renamed Tasmania).

On 24 November 1642 Abel Tasman reached and sighted the west coast of Tasmania, north of Macquarie Harbour. He named his discovery Van Diemen's Land after Antonio van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

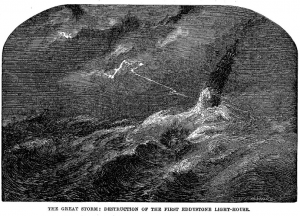

Proceeding south Tasman skirted the southern end of Tasmania and turned north-east. He then tried to work his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island where he was blown out to sea by a storm. This area he named Storm Bay. Two days later Tasman anchored to the north of Cape Frederick Hendrick just north of the Forestier Peninsula. Tasman then landed in Blackman Bay – in the larger Marion Bay. The next day, an attempt was made to land in North Bay. However, because the sea was too rough the carpenter swam through the surf and planted the Dutch flag. Tasman then claimed formal possession of the land on 3 December 1642.

Coastal cliffs of Tasman Peninsula

For two more days, he continued to follow the east coast northward to see how far it went. When the land veered to the north-west at Eddystone Point, he tried to keep in with it but his ships were suddenly hit by the Roaring Forties howling through Banks Strait. The impenetrable wind wall indicated that here was a strait, not a bay. Tasman was on a mission to find the Southern Continent, not more islands, so he abruptly turned away to the east and continued his continent-hunting.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tasmania

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abel_Tasman

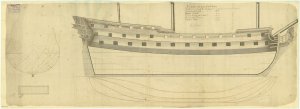

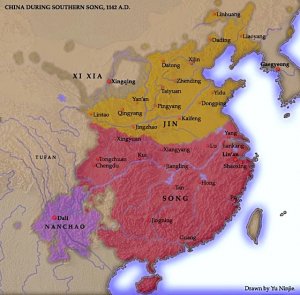

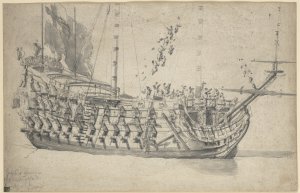

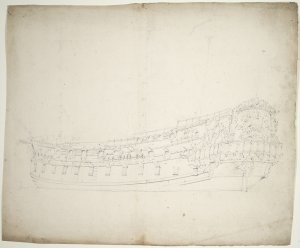

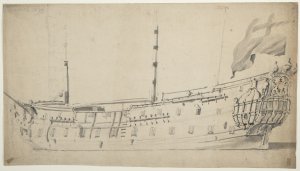

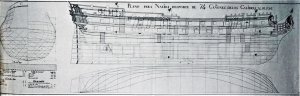

1700 – Launch of French Héros, 46 (later 50) guns, design by Pierre Coulomb, for French East India Company, and purchased June 1702 for the Navy – re-rated as 3ième Rang in 1705–08; deleted 1740.

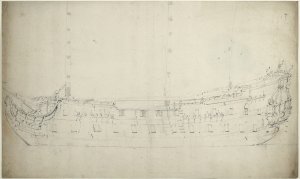

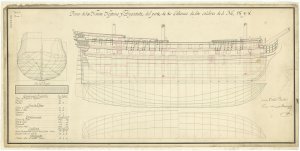

1779 – Launch of French Cérès, at Rochefort – demolished 1787.

Cérès class (32-gun design by Charles-Etienne Bombelle, with 26 x 12-pounder and 6 x 6-pounder guns).

Cérès, (launched 24 November 1779 at Rochefort) – demolished 1787.

Fée, (launched 19 April 1780 at Rochefort) – demolished 1790.

1799 - HMS Solebay (32), Cptn. Stephen Poyntz, captured L'Egyptienne (18), L'Eolan (16), La Sarier (12) and La Vengeur (8).

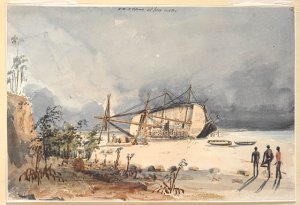

HMS Solebay (1785) was a 32-gun fifth rate launched in 1785 and wrecked in 1809. Along with HMS Derwent, they were the first ships in the West Africa Squadron that the British government had established to interdict and end the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade.

Égyptienne (1797), a corvette, captured by HMS Solebay in December 1799

Egyptienne: HMS Solebay captured her on 23 November 1799. This Egyptienne was of 300 tons burthen, was armed with 18 guns and had a crew of 140 men. She was sailing from Cape François to Jacquemel.[15] Drake, under Commander John Perkins, was in company with Solebay.

1862 - During the Civil War, the screw steam gunboat USS Monticello destroys two Confederate salt works near Little River, N.C., while the screw steam gunboat USS Sagamore captures two British blockade runners, schooner Agnes and sloop Ellen, in Indian River, Fla.

he first USS Monticello was a wooden screw-steamer in the Union Navy during the American Civil War. She was named for the home of Thomas Jefferson. She was briefly named Star in May 1861.

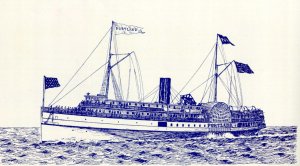

Colored print of Monticello, ca. 1860s

Monticello was built at Mystic, Connecticut, in 1859; chartered by the Navy in May 1861; and purchased on 12 September 1861 at New York from H. P. Cromwell & Company, for service in the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Captain Henry Eagle in command.

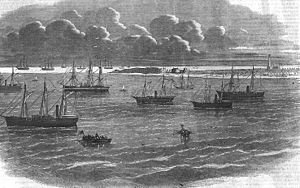

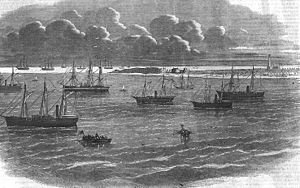

USS Sagamore was a Unadilla-class gunboat built on behalf of the United States Navy for service during the American Civil War. She was outfitted as a gunboat and assigned to the Union blockade of the Confederate States of America. Sagamore was very active during the war, and served the Union both as a patrol ship and a bombardment vessel.

USS Sagamore (1861) - USS Sagamore (3rd ship from the right) at Ship Island base,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Monticello_(1859)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Sagamore_(1861)

.

1941 - HMS Dunedin was a Danae-class light cruiser of the Royal Navy, sunk by U-124

HMS Dunedin was a Danae-class light cruiser of the Royal Navy, pennant number D93. She was launched from the yards of Armstrong Whitworth, Newcastle-on-Tyne on 19 November 1918 and commissioned on 13 September 1919. She has been the only ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name Dunedin (named for the capital of Scotland, generally Anglicised as Edinburgh).

Dunedin turning into Gardens Reach on the Brisbane River. South Brisbane wharves in background.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Dunedin

Other Events on 24 November

1642 – Abel Tasman becomes the first European to discover the island Van Diemen's Land (later renamed Tasmania).

On 24 November 1642 Abel Tasman reached and sighted the west coast of Tasmania, north of Macquarie Harbour. He named his discovery Van Diemen's Land after Antonio van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

Proceeding south Tasman skirted the southern end of Tasmania and turned north-east. He then tried to work his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island where he was blown out to sea by a storm. This area he named Storm Bay. Two days later Tasman anchored to the north of Cape Frederick Hendrick just north of the Forestier Peninsula. Tasman then landed in Blackman Bay – in the larger Marion Bay. The next day, an attempt was made to land in North Bay. However, because the sea was too rough the carpenter swam through the surf and planted the Dutch flag. Tasman then claimed formal possession of the land on 3 December 1642.

Coastal cliffs of Tasman Peninsula

For two more days, he continued to follow the east coast northward to see how far it went. When the land veered to the north-west at Eddystone Point, he tried to keep in with it but his ships were suddenly hit by the Roaring Forties howling through Banks Strait. The impenetrable wind wall indicated that here was a strait, not a bay. Tasman was on a mission to find the Southern Continent, not more islands, so he abruptly turned away to the east and continued his continent-hunting.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tasmania

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abel_Tasman

1700 – Launch of French Héros, 46 (later 50) guns, design by Pierre Coulomb, for French East India Company, and purchased June 1702 for the Navy – re-rated as 3ième Rang in 1705–08; deleted 1740.

1779 – Launch of French Cérès, at Rochefort – demolished 1787.

Cérès class (32-gun design by Charles-Etienne Bombelle, with 26 x 12-pounder and 6 x 6-pounder guns).

Cérès, (launched 24 November 1779 at Rochefort) – demolished 1787.

Fée, (launched 19 April 1780 at Rochefort) – demolished 1790.

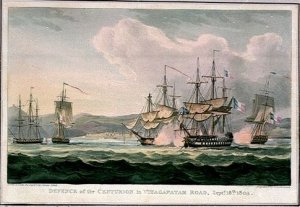

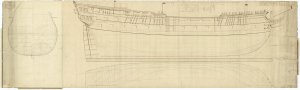

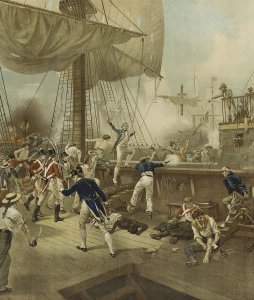

1799 - HMS Solebay (32), Cptn. Stephen Poyntz, captured L'Egyptienne (18), L'Eolan (16), La Sarier (12) and La Vengeur (8).

HMS Solebay (1785) was a 32-gun fifth rate launched in 1785 and wrecked in 1809. Along with HMS Derwent, they were the first ships in the West Africa Squadron that the British government had established to interdict and end the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade.

Égyptienne (1797), a corvette, captured by HMS Solebay in December 1799

Egyptienne: HMS Solebay captured her on 23 November 1799. This Egyptienne was of 300 tons burthen, was armed with 18 guns and had a crew of 140 men. She was sailing from Cape François to Jacquemel.[15] Drake, under Commander John Perkins, was in company with Solebay.

1862 - During the Civil War, the screw steam gunboat USS Monticello destroys two Confederate salt works near Little River, N.C., while the screw steam gunboat USS Sagamore captures two British blockade runners, schooner Agnes and sloop Ellen, in Indian River, Fla.

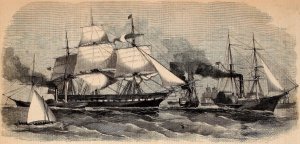

he first USS Monticello was a wooden screw-steamer in the Union Navy during the American Civil War. She was named for the home of Thomas Jefferson. She was briefly named Star in May 1861.

Colored print of Monticello, ca. 1860s

Monticello was built at Mystic, Connecticut, in 1859; chartered by the Navy in May 1861; and purchased on 12 September 1861 at New York from H. P. Cromwell & Company, for service in the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Captain Henry Eagle in command.

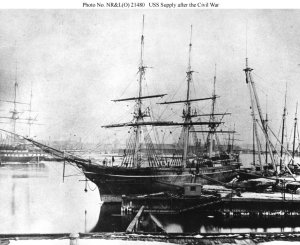

USS Sagamore was a Unadilla-class gunboat built on behalf of the United States Navy for service during the American Civil War. She was outfitted as a gunboat and assigned to the Union blockade of the Confederate States of America. Sagamore was very active during the war, and served the Union both as a patrol ship and a bombardment vessel.

USS Sagamore (1861) - USS Sagamore (3rd ship from the right) at Ship Island base,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Monticello_(1859)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Sagamore_(1861)

.

1941 - HMS Dunedin was a Danae-class light cruiser of the Royal Navy, sunk by U-124

HMS Dunedin was a Danae-class light cruiser of the Royal Navy, pennant number D93. She was launched from the yards of Armstrong Whitworth, Newcastle-on-Tyne on 19 November 1918 and commissioned on 13 September 1919. She has been the only ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name Dunedin (named for the capital of Scotland, generally Anglicised as Edinburgh).

Dunedin turning into Gardens Reach on the Brisbane River. South Brisbane wharves in background.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Dunedin