The introduction to several great books by nrique Garcia-orralba Perez defines Manga as:

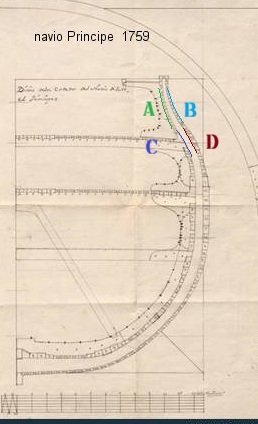

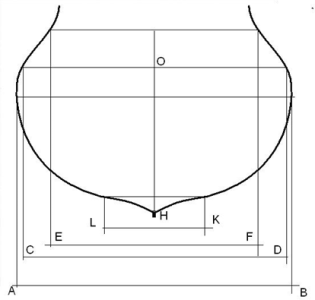

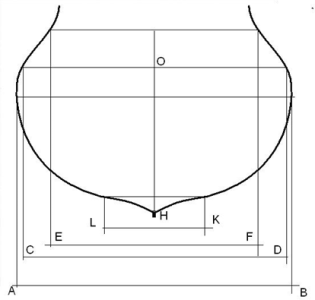

La Manga representa la anchura del buque; normalmente y por lo que aquí nos interesa, medida longitudinalmente a la altura de la Cuaderna Maestra y al nivel de la cubierta principal, de dentro a dentro, es decir, prescindiendo del grosor de los costados de la nave (C– D).

Frente a esta medida convencional, existe la Manga máxima, que se mide a la altura de la mayor anchura de la nave (A– B), que no tiene porqué coincidir con la de la cubierta principal; por el contrario, en las naves de guerra, ésta cubierta se encontraba por encima de la línea de máxima anchura, precisamente para conseguir que las portas de la artillería de esa cubierta quedaran a suficiente distancia de la línea de flotación, permitiendo utilizarla en cualquier tiempo.

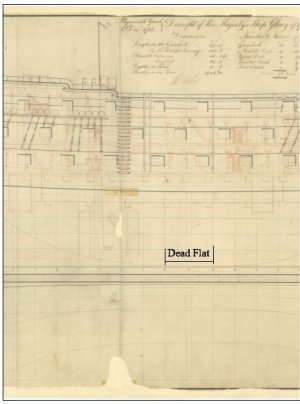

Es preciso advertir que a partir de cierto momento temporal, las cuadernas anteriores y posteriores a la maestra, se mantienen iguales que ésta, permaneciendo así en todo el cuerpo central del buque, es decir, entre el redel de proa y el redel de popa, a partir de cuyas posiciones las cuadernas se van afinando.

Basically, "t]he Manga represents the width of the ship; Normally and for what interests us here, measured longitudinally at the height of the Master Frame and at the level of the main deck, from inside to inside, that is, regardless of the thickness of the sides of the ship (C–D).Opposite to this conventional measurement, there is the Maximum Beam, which is measured at the height of the greatest width of the ship (A–B), which does not have to coincide with that of the main deck ..."

However, in his book Las Fragatas de Vela de La Armada Espanola (1600 - 1850) on page 258 he says:

Notas.- ...

2ª.- Las dimensiones de eslora y manga ya no se miden por la parte interior del buque, o “de dentro a dentro”, sino por su parte exterior o “de fuera a fuera”, lo que resulta imprescindible tener en cuenta a efectos de comparación con unidades anteriores.

which means:

Notes.- ...

2nd.- The length and beam dimensions are no longer measured from the inside of the ship, or 'from inside to inside,' but from its exterior or 'from outside to outside,' which is essential to take into account for comparison with earlier units.

This refers to a table of Spanish Frigates Circa 1770-1773.

The book Spanish Warships in the Age of Sail 1700-1860 page 12 defines manga as "the beam of the ship, measured at its widest point at the midpoint of the length" which seems wrong to me as that is the Manga Maxima and the widest point of the ship would be slightly forward of the midpoint of its length. However, my understanding is that regular ship's width is at the main deck outside to outside. (I have seen one source using the frame, no planks, can't remember if that was inside or outside.)

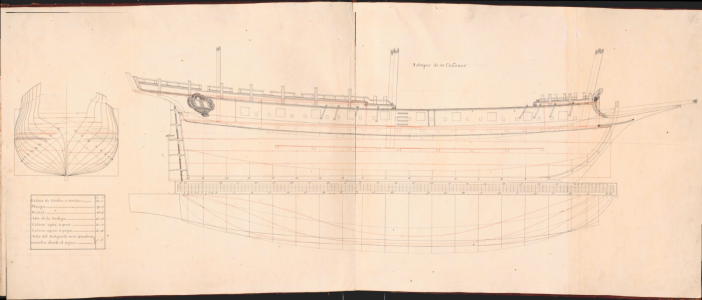

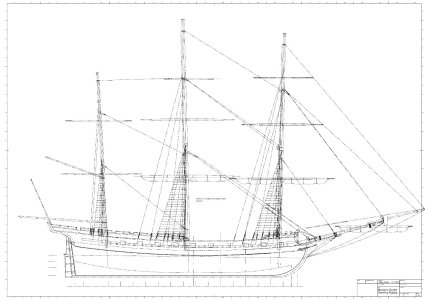

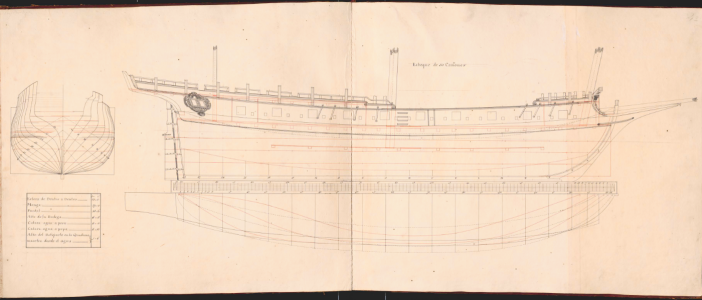

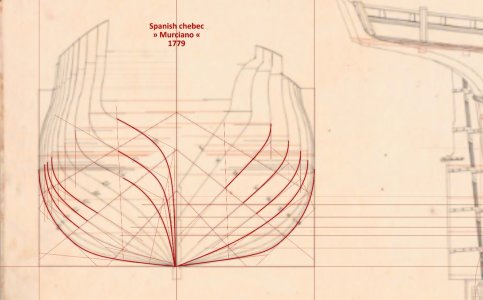

I am trying to create a body plan for a Spanish jabeque in 1779. So, what do I do? I have several sources providing the manga measurement but is that inside to inside or outside to outside?

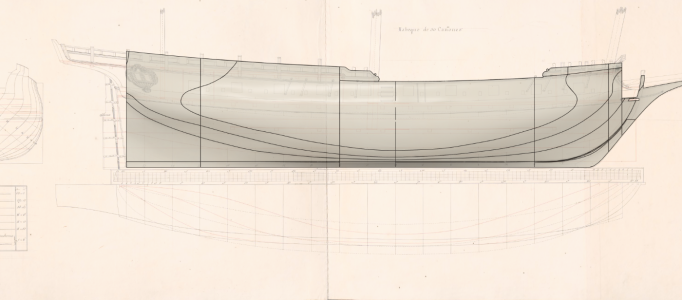

Now it gets interesting. The original plan book was circa 1750, my target ship Murciano ordered 1779 to modified, improved larger dimensions, and the dimensions simply stated by Perez (and other sources) without comment on whether the manga measure is inside or outside. The only plan is the plan book, made at the time of inside measure, and I presume the body plan inks the lines for the inside of the hull. Presumably, and regardless of whether the later ship order used inside or outside measurements, I need to add interior planking, the frame and exterior planking outside of that line to produce the cut-profile of the hull, right? Which is fun because although I can easily get the plank thickness for various layers, I have to punt on tapering the frame thicker as it nears the keel.

All advice, opinions, facts welcome.

Thanks!

La Manga representa la anchura del buque; normalmente y por lo que aquí nos interesa, medida longitudinalmente a la altura de la Cuaderna Maestra y al nivel de la cubierta principal, de dentro a dentro, es decir, prescindiendo del grosor de los costados de la nave (C– D).

Frente a esta medida convencional, existe la Manga máxima, que se mide a la altura de la mayor anchura de la nave (A– B), que no tiene porqué coincidir con la de la cubierta principal; por el contrario, en las naves de guerra, ésta cubierta se encontraba por encima de la línea de máxima anchura, precisamente para conseguir que las portas de la artillería de esa cubierta quedaran a suficiente distancia de la línea de flotación, permitiendo utilizarla en cualquier tiempo.

Es preciso advertir que a partir de cierto momento temporal, las cuadernas anteriores y posteriores a la maestra, se mantienen iguales que ésta, permaneciendo así en todo el cuerpo central del buque, es decir, entre el redel de proa y el redel de popa, a partir de cuyas posiciones las cuadernas se van afinando.

Basically, "t]he Manga represents the width of the ship; Normally and for what interests us here, measured longitudinally at the height of the Master Frame and at the level of the main deck, from inside to inside, that is, regardless of the thickness of the sides of the ship (C–D).Opposite to this conventional measurement, there is the Maximum Beam, which is measured at the height of the greatest width of the ship (A–B), which does not have to coincide with that of the main deck ..."

However, in his book Las Fragatas de Vela de La Armada Espanola (1600 - 1850) on page 258 he says:

Notas.- ...

2ª.- Las dimensiones de eslora y manga ya no se miden por la parte interior del buque, o “de dentro a dentro”, sino por su parte exterior o “de fuera a fuera”, lo que resulta imprescindible tener en cuenta a efectos de comparación con unidades anteriores.

which means:

Notes.- ...

2nd.- The length and beam dimensions are no longer measured from the inside of the ship, or 'from inside to inside,' but from its exterior or 'from outside to outside,' which is essential to take into account for comparison with earlier units.

This refers to a table of Spanish Frigates Circa 1770-1773.

The book Spanish Warships in the Age of Sail 1700-1860 page 12 defines manga as "the beam of the ship, measured at its widest point at the midpoint of the length" which seems wrong to me as that is the Manga Maxima and the widest point of the ship would be slightly forward of the midpoint of its length. However, my understanding is that regular ship's width is at the main deck outside to outside. (I have seen one source using the frame, no planks, can't remember if that was inside or outside.)

I am trying to create a body plan for a Spanish jabeque in 1779. So, what do I do? I have several sources providing the manga measurement but is that inside to inside or outside to outside?

Now it gets interesting. The original plan book was circa 1750, my target ship Murciano ordered 1779 to modified, improved larger dimensions, and the dimensions simply stated by Perez (and other sources) without comment on whether the manga measure is inside or outside. The only plan is the plan book, made at the time of inside measure, and I presume the body plan inks the lines for the inside of the hull. Presumably, and regardless of whether the later ship order used inside or outside measurements, I need to add interior planking, the frame and exterior planking outside of that line to produce the cut-profile of the hull, right? Which is fun because although I can easily get the plank thickness for various layers, I have to punt on tapering the frame thicker as it nears the keel.

All advice, opinions, facts welcome.

Thanks!

Last edited: