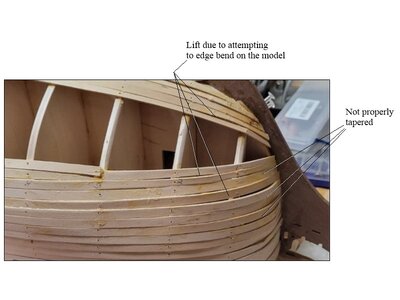

I agree... sort of. I believe I qualified my observation by saying that edge-setting plank on a model "makes attempting to bend it simultaneously in a direction 90 degrees to another direction

a very difficult exercise." That isn't to say it becomes impossible and, with the more cooperative wood species and some practice, it can be done quite effectively. Importantly, such "radical" edge-setting still requires a perfectly spiled plank shape to both edges of the curving-tapered plank, so the savings in labor is somewhat illusory. If you are going to have to spile the plank shape, it's a lot easier to spile it as needed in the first instance than to spile and then bend in the edge-set, although reasonable minds may differ on this point. The wood in the picture is probably either Alaskan yellow cedar or Costello boxwood. Strip wood of those species is available only in the highest quality (and priced) kits, or as optional after-market upgrades to such kits. I don't think that the low-quality walnut and (faux?) mahoganies that are commonly encountered in kits would yield such impressive results.

This is another example of the truth of the maxim: "There's no free lunch." As you note, the problem arises from the kit manufacturers' desire to cut production materials and packaging and shipping costs. (e.g.: The shift to plank-on-bulkhead framing was likely motivated by the advantage it created in packaging over machine-shaped solid hull blanks, not because it produces an easier to build or "more authentic," model as some of their advertising suggests.) The customary 24" strip wood length also accommodates standard shipping rates. Longer lengths substantially increase the postal rates. These facts well illustrate the advantage of proper stock sourcing over taking what the kit gives you and trying to compensate for that, at which point one may as well scratch build the model from available plans in the first place. In that case, the work is greatly reduced by the availability of the "Byrnes trifecta," a highly accurate thin-kerf-bladed micro saw, thickness planer, and disk sander, although these aren't essential and can be replaced by decent hand tools and patience. A band saw and/or larger table saw and perhaps a jointer and larger-scale thickness planer (perhaps by occasionally accessing the same from a well-equipped woodworking friend or cabinet shop) will enable one to become entirely self-sufficient to mill their own stock from raw timber which may even sometimes be had for nothing from your friendly tree service. I mention this not because I own stock in Byrnes Model Machines, but because for anyone who intends to do any amount of ship modeling, the savings in wood material available by in-house milling not only provides the greatest flexibility in sizing one's stock material but provides savings in materials costs which quickly amortize the initial expense of the machinery involved. (And the machinery may well be worth more used than you paid for it, if recent used prices are any indication!)

The way (bending wood) was explained" to you is incorrect. I mention this just because it's a common misconception that bugs me whenever I encounter it. The water (or steam)

does not "soften the lignin in the wood." It is the

heat that softens the lignin, which hardens up again when it cools. This is why wood doesn't turn into a limp noodle when it rains. It's only that steam, or hot water, was, and is still, the best medium with which to

transfer heat to the wood, which is why green wood with a higher moisture content is the best bending stock in "real life" sizes. Hence, the common use of steam boxes in full-scale boat and ship building. (And more so in boat building, since it takes a lot of steam to bend larger timbers (the rule of thumb being one hour of steaming for each inch of wood thickness) they are usually sawn to shape. Just "wetting" the piece won't do much good, though, because the moisture content of the wood has to be raised throughout to be effective, not just on the outside faces of the piece, if the heat transfer is to be even throughout the piece. So, for a modeler, placing a small piece of wood in a pot of boiling water will work fine to soften it, but then you've got a wet piece of wood that isn't going to glue up very well and so you've got to clamp it in place until it dries before you glue it, not to mention risk scalding your fingers with boiling water doing it! Just soaking the wood in water isn't going to do much of anything for bending it. (Not to mention that some species bend rather well and others nearly not at all.) All one needs is a suitable heat source and many approaches are available. A hot hair dryer or heat gun will work. So will bending wood over a heated former, such as a piece of metal pipe or an empty tin can with a propane torch applied to the inside of the metal tube. (But

do not put a torch to galvanized metal pipe! The fumes from highly heated zinc are very poisonous.) A soldering, curling, or clothes iron will work well, too. The best of all is one of the no-longer-in-production Aeropiccola plank bending irons, if you can find one on eBay. It has a spring-loaded bail on the "French curve" shaped heated head that will hold the stock against the Fibonacci curve shaped head to work a tight curve of any shape desired right up to the end of the piece using but one hand holding the "cold" end of the stock. (While others' mileage may vary, I've found that the "crimping pliers" and "pinch wheels" now sold by some outfits for shaping bends are next to useless.)

View attachment 463569

View attachment 463570

There's now a similar bending iron on the market with a round head that's sold with a wooden block with a curve cut in it so the workpiece can be formed by pressing the round head into the curved shape cut in the block. It works, but not nearly as well as the Aeropiccola model. Why Aeropiccola quit making them is anyone's guess. It's a simple casting that could be attached to any cheap soldering iron.

It also bears noting that the curing of PVA adhesive can be greatly accelerated by applying heat to the joint. By placing a hot iron on the outside of a plank with PVA applied to the faying surfaces, the heat will cause the moisture in the PVA to evaporate quickly, causing the PVA to solidify. (Obviously, this technique works best on

dry wood, not stuff that's soaking wet!) In this fashion, planks can be quickly "tacked" to frames or bulkheads, often without the need for any clamping at all. It goes without saying that care does have to be taken not to burn the surface of the wood with the heating source.