.

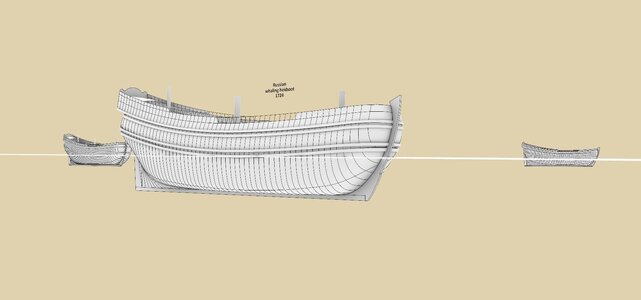

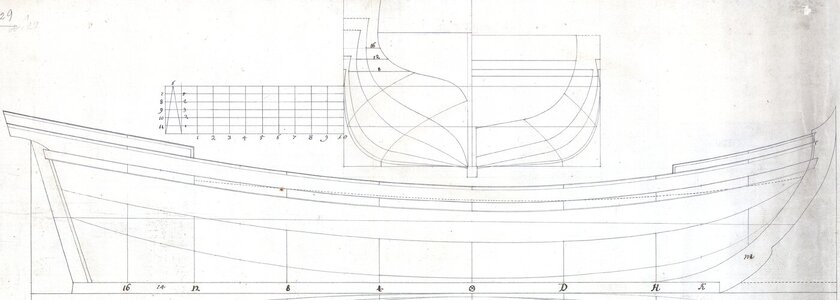

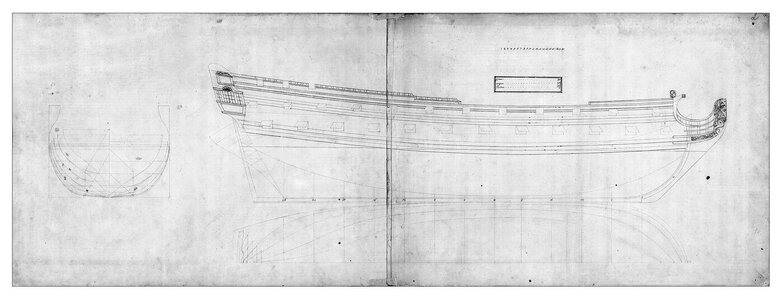

As the title of this thread suggests, this important plan from the early decades of the 18th century demonstrates the next stage in the development of design methods in the Northern Continental/Dutch tradition. This particular plan of a Russian whaling ship of 1724, kindly pointed out to me by Martes, was drawn by an experienced commercial shipwright from Arkhangelsk, Nikifor Bazhenin, for the construction of three whaling vessels intended for the newly formed fishing company – Whale 1725, Greenland Ship 1725 and Great Fishery 1725 (for more on this see V. V. Bryzgalov, O. V. Ovsyannikov, The Project of Peter the Great: State-Owned Fishing Company ‘Kola Whaling’ (1723–1760), [in:] Collection of Works of the Arkhangelsk Centre of The Russian Geographical Society, 9/2021; in Russian).

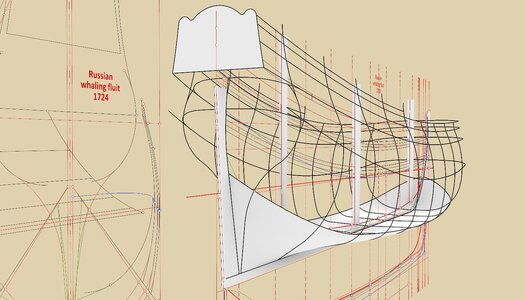

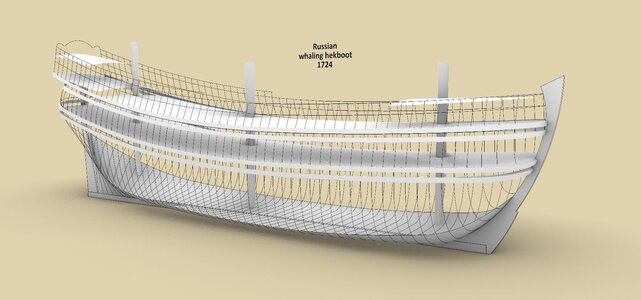

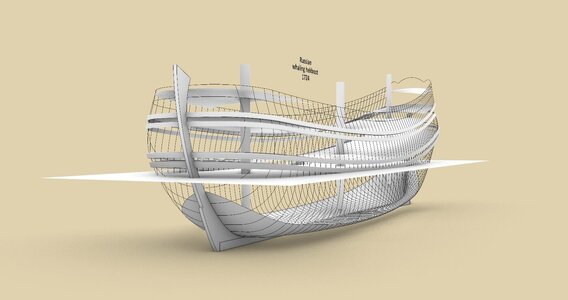

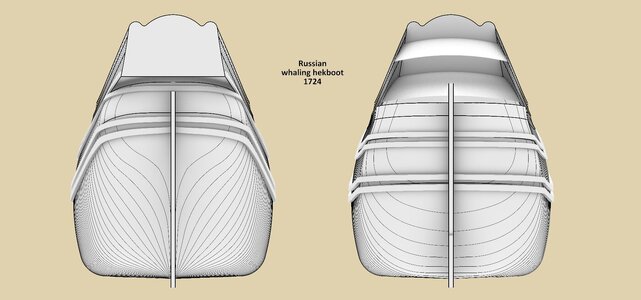

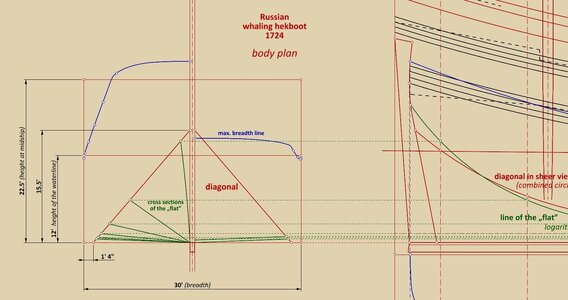

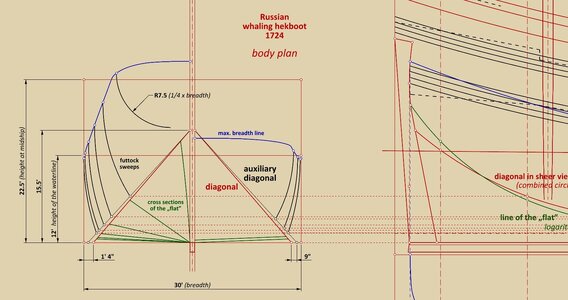

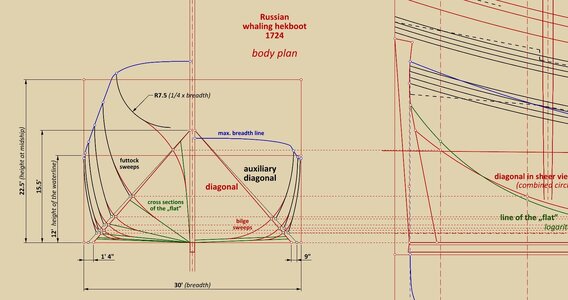

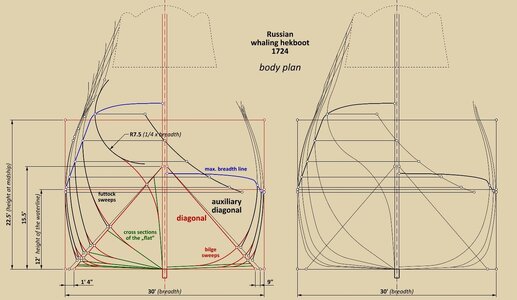

An interesting special feature of the concept of this vessel is that it illustrates the process of introduction to traditional, existing design methods in the North Continental/Dutch tradition of a relatively new invention – the increasingly prevalent design diagonals. It should be emphasised that the diagonal, still singular in this design, is not merely a verification, but a legitimate design element, actually used to form the shape of the ship's hull.

On the other hand, this design is still firmly grounded in the North Continental/Dutch tradition, as the base of the design is still the ‘flat’ surface forming the bottom of the hull. Nevertheless, the rather ingenious – indeed quite straightforward – use of the design diagonal has made it possible to easily obtain bilge sweeps of variable radii and consequently to form the hull shape in a more flexible way. It could also be said that the concept of this design is quite similar to the design of a Dutch frigate ca. 1700 described in the thread Dutch heavy frigate ca. 1700 – engineering or carpentry ‘snowman’ making?, whilst at the same time being already noticeably more advanced.

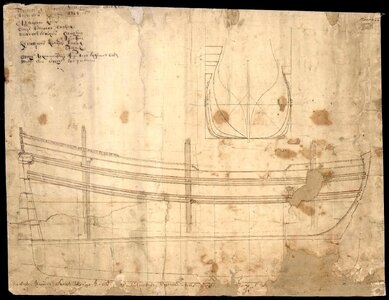

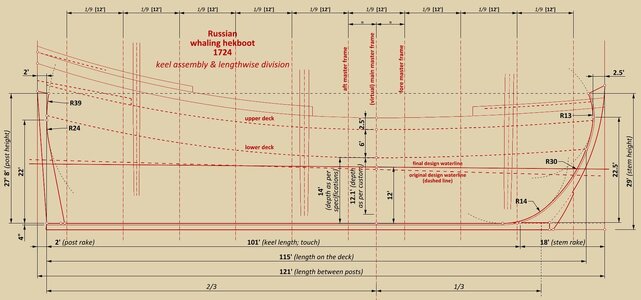

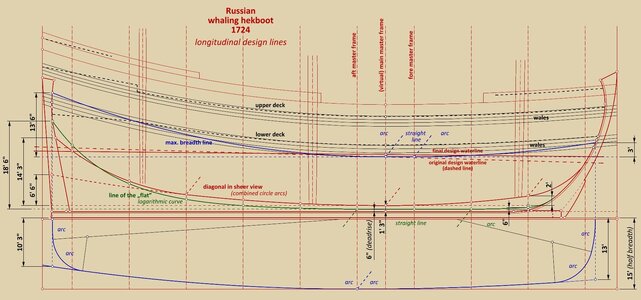

Reproduction of the original plan of a whaling ship from 1724 (Russian archives):

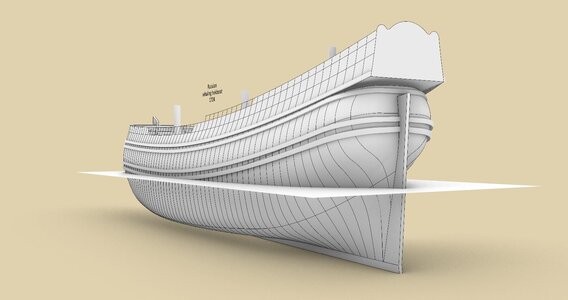

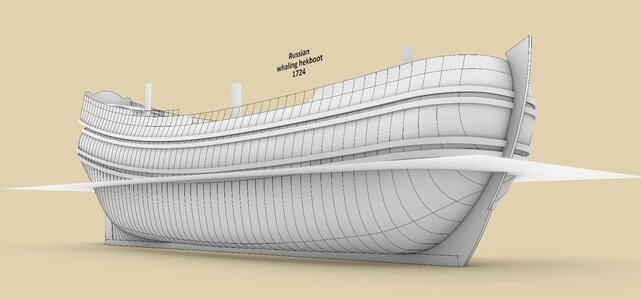

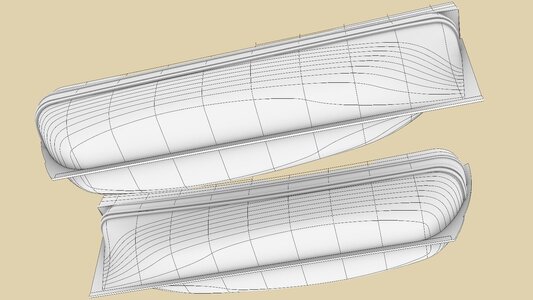

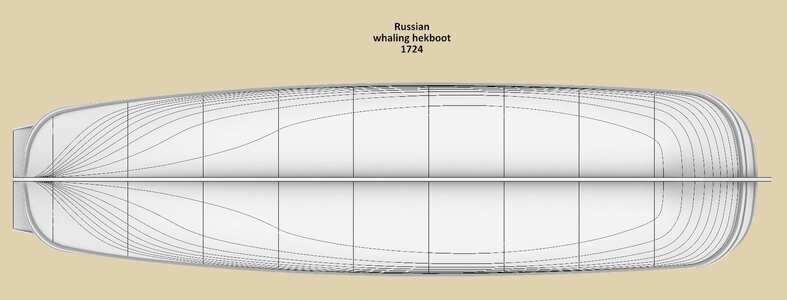

And some already-made graphics illustrating the ship's hull shapes, obtained with a new, fairly recent design system (compared to previous, 17th-century practices):

.