Hello again, everyone. I have a quick question for a beginner completing my first kit. I'd like to know what your sanding and shaping setup looks like. I received a small sanding block in my kit, but it doesn't seem to work very well. There are many options out there for sanding blocks, foam pads, sanding sticks, etc. What do you all prefer to use for different applications? Are there specific grits that are the most commonly used? Thank you for your patience as I figure out the basics over here. I appreciate your input!

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

LOL. The easy answer is just like clamps, you can never have enough shapes and types of sanding blocks nor enough sandpaper.  I use everything from a large oscillating spindle sander all down to a 1/4" wide sanding stick and grits from 60 (for the really rough shaping) down to 320. I do have some really fine grit sandpaper (up to 10000) if I need to polish something like clear plastic.

I use everything from a large oscillating spindle sander all down to a 1/4" wide sanding stick and grits from 60 (for the really rough shaping) down to 320. I do have some really fine grit sandpaper (up to 10000) if I need to polish something like clear plastic.

Hello and welcome — that’s an excellent question, and you’re definitely not alone. Most kit sanding blocks are only a starting point (if any), and many builders replace or supplement them fairly quickly. Below is a simple, effective sanding setup that works well for most model ship work, IMHOHello again, everyone. I have a quick question for a beginner completing my first kit. I'd like to know what your sanding and shaping setup looks like. I received a small sanding block in my kit, but it doesn't seem to work very well. There are many options out there for sanding blocks, foam pads, sanding sticks, etc. What do you all prefer to use for different applications? Are there specific grits that are the most commonly used? Thank you for your patience as I figure out the basics over here. I appreciate your input!

Sanding blocks (flat work). For straight runs like bulkhead fairing, deck edges, and hull planking:

A hard sanding block (made of wood, acrylic, or cork) is essential; it keeps surfaces flat. You can easily make your own by gluing sandpaper to a small piece of wood or MDF. These work far better than soft kit blocks for shaping hulls.

Sanding sticks (general shaping). For edges, curves, and controlled material removal: Sanding sticks or nail files (the hobby type, not coarse drugstore ones) are very useful. Different shapes (flat, tapered, and rounded) help you reach tight areas. These are great for beveling bulkheads before planking.

Foam sanding pads (curves & finishing). For final smoothing and curved surfaces: Foam-backed sanding pads conform to gentle curves without digging in. Excellent for final hull smoothing after planking. Use light pressure, let the grit do the work.

Useful grit range (you don’t need everything). A small, sensible progression is:

- 120–150 grit → heavy shaping/fairing

- 220–240 grit → general smoothing (most-used)

- 320–400 grit → pre-finish smoothing

- 600+ grit → final finish (optional, before paint)

A key beginner tip: Use long strokes, especially on hulls, and avoid sanding in one small spot. Check symmetry often (by eye and by touch). Stop early and check; it’s much easier to remove more material than to put it back.

Here is my personal like tip: Wrapping sandpaper around a ruler, a dowel, a scrap strip of wood, a rubber shape … gives you custom tools for almost any shape.

Finally, don’t worry about having “the perfect tools” - technique matters far more than brand. With a few basic blocks, sticks, and the right grits, you’ll be well-equipped.

Sorry for the long writing, hope this will give a basic idea.

- Joined

- Sep 10, 2024

- Messages

- 919

- Points

- 353

And as one of my woodturning mentors used to say, "Use sandpaper as though someone else was paying for it!"

That means that even though there may be grit left on a piece of sand paper, after a while it will be dull. Sandpaper is a cutting tool like any other and must be sharp to do its work. Pressing harder with dull sandpaper only causes friction which causes heat and will actually glaze and work-harden the surface of the wood (yes, even wood) and makes it harder to cut through that glaze with subsequent grits.

You can't take a piece of worn 120 grit and "downgrade" it, calling it 240. When it's dull, it's dull. Use only the coarsest paper necessary to remove machine (or hand) tool marks and do final shaping. Then, use subsequent grits only to remove the scratches left by the previous grit - always sanding with the grain. Cross-grain scratches are very difficult to remove. Don't skip grits. Use the +50% rule to determine the next grit to use. That means if you start with 120, 50% of that is 60. Added to the 120 gives you 180. That's your next grit. 50% of that is 90 - added to it is 270 - but the next nominal size is 240. Etc. and so on.

Progressing through the grits does not take longer! I guarantee that if we both started with 100 grit paper and wanted to end up with a polished 600 grit finish, I would get there much faster progressing through all the grits than you would skipping from 100 directly to 600.

This is not BS - it comes from 50 years of woodworking and woodturning.

That means that even though there may be grit left on a piece of sand paper, after a while it will be dull. Sandpaper is a cutting tool like any other and must be sharp to do its work. Pressing harder with dull sandpaper only causes friction which causes heat and will actually glaze and work-harden the surface of the wood (yes, even wood) and makes it harder to cut through that glaze with subsequent grits.

You can't take a piece of worn 120 grit and "downgrade" it, calling it 240. When it's dull, it's dull. Use only the coarsest paper necessary to remove machine (or hand) tool marks and do final shaping. Then, use subsequent grits only to remove the scratches left by the previous grit - always sanding with the grain. Cross-grain scratches are very difficult to remove. Don't skip grits. Use the +50% rule to determine the next grit to use. That means if you start with 120, 50% of that is 60. Added to the 120 gives you 180. That's your next grit. 50% of that is 90 - added to it is 270 - but the next nominal size is 240. Etc. and so on.

Progressing through the grits does not take longer! I guarantee that if we both started with 100 grit paper and wanted to end up with a polished 600 grit finish, I would get there much faster progressing through all the grits than you would skipping from 100 directly to 600.

This is not BS - it comes from 50 years of woodworking and woodturning.

- Joined

- Jun 29, 2024

- Messages

- 1,416

- Points

- 393

I am one of those modelers that never throws anything away. I have a box on my workbench when I keep wood scraps. I use them over and over for jigs, fixtures, and yes sanding blocks. I have never found a need for commercially made sanding blocks.

Roger

Roger

You may want to consider and try scrapers as well. A stiff back razor work really well and are better than sanding in some situations such as finishing deck planking.

Amen to that! And not just flat scrapers. You can buy shaped scrapers or grind your own shapes from razor blades, lengths of hacksaw blades, or whatever and quickly form moldings.

As the poster is a novice, I will add to the above answers that sandpaper seems, IMHO, to be grossly overused these days as a shaping tool. A form that can be scraped, planed, cut, sawn, or filed to shape is best formed with a scraper, a plane, a knife, a saw, or a file, respectively. You can get to the same place with with sandpaper, but generally at the cost of rounded corners and a rough surface. It just doesn't look the same when made with sandpaper rather than a properly sharpened edged tool, not to mention that sanding dust makes a huge mess. I used to shape with sandpaper long ago but have gotten to the point where I really don't use sandpaper at all, other than for finishing preparation.

Thank you for the thorough answer, Jim. I really appreciate the helpful information!Hello and welcome — that’s an excellent question, and you’re definitely not alone. Most kit sanding blocks are only a starting point (if any), and many builders replace or supplement them fairly quickly. Below is a simple, effective sanding setup that works well for most model ship work, IMHO

Sanding blocks (flat work). For straight runs like bulkhead fairing, deck edges, and hull planking:

A hard sanding block (made of wood, acrylic, or cork) is essential; it keeps surfaces flat. You can easily make your own by gluing sandpaper to a small piece of wood or MDF. These work far better than soft kit blocks for shaping hulls.

Sanding sticks (general shaping). For edges, curves, and controlled material removal: Sanding sticks or nail files (the hobby type, not coarse drugstore ones) are very useful. Different shapes (flat, tapered, and rounded) help you reach tight areas. These are great for beveling bulkheads before planking.

Foam sanding pads (curves & finishing). For final smoothing and curved surfaces: Foam-backed sanding pads conform to gentle curves without digging in. Excellent for final hull smoothing after planking. Use light pressure, let the grit do the work.

Useful grit range (you don’t need everything). A small, sensible progression is:

You’ll spend most of your time in the 220–320 range, IMHO

- 120–150 grit → heavy shaping/fairing

- 220–240 grit → general smoothing (most-used)

- 320–400 grit → pre-finish smoothing

- 600+ grit → final finish (optional, before paint)

A key beginner tip: Use long strokes, especially on hulls, and avoid sanding in one small spot. Check symmetry often (by eye and by touch). Stop early and check; it’s much easier to remove more material than to put it back.

Here is my personal like tip: Wrapping sandpaper around a ruler, a dowel, a scrap strip of wood, a rubber shape … gives you custom tools for almost any shape.

Finally, don’t worry about having “the perfect tools” - technique matters far more than brand. With a few basic blocks, sticks, and the right grits, you’ll be well-equipped.

Sorry for the long writing, hope this will give a basic idea.

I have another quick question. What is your setup for clamps and rigging to hold parts in place while the glue dries? I have a few small plastic clamps and some metal spring clamps, but that's about it. What do you use to secure larger items or hold oddly shaped pieces in place?Hello and welcome — that’s an excellent question, and you’re definitely not alone. Most kit sanding blocks are only a starting point (if any), and many builders replace or supplement them fairly quickly. Below is a simple, effective sanding setup that works well for most model ship work, IMHO

Sanding blocks (flat work). For straight runs like bulkhead fairing, deck edges, and hull planking:

A hard sanding block (made of wood, acrylic, or cork) is essential; it keeps surfaces flat. You can easily make your own by gluing sandpaper to a small piece of wood or MDF. These work far better than soft kit blocks for shaping hulls.

Sanding sticks (general shaping). For edges, curves, and controlled material removal: Sanding sticks or nail files (the hobby type, not coarse drugstore ones) are very useful. Different shapes (flat, tapered, and rounded) help you reach tight areas. These are great for beveling bulkheads before planking.

Foam sanding pads (curves & finishing). For final smoothing and curved surfaces: Foam-backed sanding pads conform to gentle curves without digging in. Excellent for final hull smoothing after planking. Use light pressure, let the grit do the work.

Useful grit range (you don’t need everything). A small, sensible progression is:

You’ll spend most of your time in the 220–320 range, IMHO

- 120–150 grit → heavy shaping/fairing

- 220–240 grit → general smoothing (most-used)

- 320–400 grit → pre-finish smoothing

- 600+ grit → final finish (optional, before paint)

A key beginner tip: Use long strokes, especially on hulls, and avoid sanding in one small spot. Check symmetry often (by eye and by touch). Stop early and check; it’s much easier to remove more material than to put it back.

Here is my personal like tip: Wrapping sandpaper around a ruler, a dowel, a scrap strip of wood, a rubber shape … gives you custom tools for almost any shape.

Finally, don’t worry about having “the perfect tools” - technique matters far more than brand. With a few basic blocks, sticks, and the right grits, you’ll be well-equipped.

Sorry for the long writing, hope this will give a basic idea.

There isn’t a single “right” setup; different parts and joints call for different solutions, and the type of glue you’re using matters too. Most of us rely on a mix of:I have another quick question. What is your setup for clamps and rigging to hold parts in place while the glue dries? I have a few small plastic clamps and some metal spring clamps, but that's about it. What do you use to secure larger items or hold oddly shaped pieces in place?

- small spring or plastic clamps for simple joints. You cannot have enough of those, as Jeff mentioned in the above post.

- rubber bands and masking tape for curved or awkward shapes

- pins or needles in a building board for alignment

- weights for flat parts like decks

- thread or light cord where clamps won’t reach

One of our favorite sayings is that you can never have too many clamps !

Excellent precious information.And as one of my woodturning mentors used to say, "Use sandpaper as though someone else was paying for it!"

That means that even though there may be grit left on a piece of sand paper, after a while it will be dull. Sandpaper is a cutting tool like any other and must be sharp to do its work. Pressing harder with dull sandpaper only causes friction which causes heat and will actually glaze and work-harden the surface of the wood (yes, even wood) and makes it harder to cut through that glaze with subsequent grits.

You can't take a piece of worn 120 grit and "downgrade" it, calling it 240. When it's dull, it's dull. Use only the coarsest paper necessary to remove machine (or hand) tool marks and do final shaping. Then, use subsequent grits only to remove the scratches left by the previous grit - always sanding with the grain. Cross-grain scratches are very difficult to remove. Don't skip grits. Use the +50% rule to determine the next grit to use. That means if you start with 120, 50% of that is 60. Added to the 120 gives you 180. That's your next grit. 50% of that is 90 - added to it is 270 - but the next nominal size is 240. Etc. and so on.

Progressing through the grits does not take longer! I guarantee that if we both started with 100 grit paper and wanted to end up with a polished 600 grit finish, I would get there much faster progressing through all the grits than you would skipping from 100 directly to 600.

This is not BS - it comes from 50 years of woodworking and woodturning.

I would like to add beating of the sandpaper now and then between the sanding periods and before it becomes completely dull helps to use it longer, because allready sanded wood particles between the grains can be partly removed and do not agglomerate on the sandpaper. For vacuum sanding is this not valid because the are sucked of iimmediately during sanding

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2024

- Messages

- 178

- Points

- 78

The trouble with abrasives (not made of sand these days) is that people think they are for removing material.

There is good advice above, and my two penn’orth is that you should be aiming to cut timber to size rather than abrade it. That way, you get corners where you should have them, and you work to tighter tolerances.

Then, if you have to use an abrasive, you always, always use it on a block. Not doing so means you round off those corners, the ends of planks, the edges of planks, and so forth. Make up a series of ply or mdf ‘fingers’ and glue abrasives to them. Glue a slightly oversize bit of abrasive, then cut to size with a scalpel so you have a crisp corner.

For added sophistication you make up a shooting board so that you can use a block mounted abrasive as a precision dimensioning tool.

Your choice of medium also matters. There are hundreds of abrasives out there, using all manner of materials as grit, and all sorts of substrate. Just as there are different edge tools for wood and metal, so there are different abrasives. Some will clog more easily than others, some will cut better in wood than others, and, to be honest, some you can find in shops/supply houses more easily than others. For myself, I’ve settled on a stearated paper as my ‘stock’ and I buy it in rolls in grits from 80 to 400, with 240 and 320 being most used for models. 400 and beyond is generally for finishing and polishing. (And sharpening)

Allan mentioned scrapers' and he is SO right. But look up cabinet scrapers and how to sharpen them and turn a burr, then apply that to a miniature scraper you make about a half inch or 10mm wide. Just the thing for .decks. You can produce a profile with a file for, say a convex, ,or concave, curve on the hull too, and you end up with a clear grain from the tool finish that will take french polish and dazzle the onlooker with the chatoyance. Compared with which sanding leaves a muddier look under varnish.

But then, paint and green growths and barnacles under the waterline is the way to go, with weathering above the water.

J

There is good advice above, and my two penn’orth is that you should be aiming to cut timber to size rather than abrade it. That way, you get corners where you should have them, and you work to tighter tolerances.

Then, if you have to use an abrasive, you always, always use it on a block. Not doing so means you round off those corners, the ends of planks, the edges of planks, and so forth. Make up a series of ply or mdf ‘fingers’ and glue abrasives to them. Glue a slightly oversize bit of abrasive, then cut to size with a scalpel so you have a crisp corner.

For added sophistication you make up a shooting board so that you can use a block mounted abrasive as a precision dimensioning tool.

Your choice of medium also matters. There are hundreds of abrasives out there, using all manner of materials as grit, and all sorts of substrate. Just as there are different edge tools for wood and metal, so there are different abrasives. Some will clog more easily than others, some will cut better in wood than others, and, to be honest, some you can find in shops/supply houses more easily than others. For myself, I’ve settled on a stearated paper as my ‘stock’ and I buy it in rolls in grits from 80 to 400, with 240 and 320 being most used for models. 400 and beyond is generally for finishing and polishing. (And sharpening)

Allan mentioned scrapers' and he is SO right. But look up cabinet scrapers and how to sharpen them and turn a burr, then apply that to a miniature scraper you make about a half inch or 10mm wide. Just the thing for .decks. You can produce a profile with a file for, say a convex, ,or concave, curve on the hull too, and you end up with a clear grain from the tool finish that will take french polish and dazzle the onlooker with the chatoyance. Compared with which sanding leaves a muddier look under varnish.

But then, paint and green growths and barnacles under the waterline is the way to go, with weathering above the water.

J

I really appreciate the advice, Jim. This has been very helpful. Would you mind explaining what a shooting board is? I appreciate your attention to detail in your explanation; I am a detail-oriented person myself, so the more information I can get, the better.The trouble with abrasives (not made of sand these days) is that people think they are for removing material.

There is good advice above, and my two penn’orth is that you should be aiming to cut timber to size rather than abrade it. That way, you get corners where you should have them, and you work to tighter tolerances.

Then, if you have to use an abrasive, you always, always use it on a block. Not doing so means you round off those corners, the ends of planks, the edges of planks, and so forth. Make up a series of ply or mdf ‘fingers’ and glue abrasives to them. Glue a slightly oversize bit of abrasive, then cut to size with a scalpel so you have a crisp corner.

For added sophistication you make up a shooting board so that you can use a block mounted abrasive as a precision dimensioning tool.

Your choice of medium also matters. There are hundreds of abrasives out there, using all manner of materials as grit, and all sorts of substrate. Just as there are different edge tools for wood and metal, so there are different abrasives. Some will clog more easily than others, some will cut better in wood than others, and, to be honest, some you can find in shops/supply houses more easily than others. For myself, I’ve settled on a stearated paper as my ‘stock’ and I buy it in rolls in grits from 80 to 400, with 240 and 320 being most used for models. 400 and beyond is generally for finishing and polishing. (And sharpening)

Allan mentioned scrapers' and he is SO right. But look up cabinet scrapers and how to sharpen them and turn a burr, then apply that to a miniature scraper you make about a half inch or 10mm wide. Just the thing for .decks. You can produce a profile with a file for, say a convex, ,or concave, curve on the hull too, and you end up with a clear grain from the tool finish that will take french polish and dazzle the onlooker with the chatoyance. Compared with which sanding leaves a muddier look under varnish.

But then, paint and green growths and barnacles under the waterline is the way to go, with weathering above the water.

J

- Joined

- Oct 2, 2025

- Messages

- 152

- Points

- 78

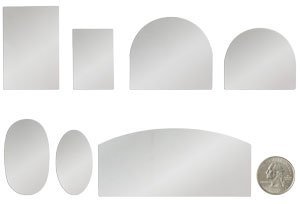

There are commercial products if you are willing to afford them:

Peachtree Woodworking Supply Inc. , Atlanta, GA

Fulton 7 Piece Mini Scraper Set

This scraper set is designed to be used for fine, detailed workpieces. Great for smoothing between lacquer applications on curved pieces and restoration work where small detail work is needed.

Scraper sizes:

1-1/8" x 1-3/4"

1-9/16" x 2-11/32"

1-1/16" x 1-27/32"

1-5/16" x 2-5/32"

2-1/16" x 1-3/4"

2-3/8" x 2-5/32"

4-5/16" x 1-5/16"

1757 7 Piece Mini Scraper Set

$24.99

There are luthiers supply sites selling these for about twice the price.

*

StewMac Ultimate Scraper Mini

Item # 103470 In stock, ready to ship!

$34.49

*

Lee Valley Tools Ltd.

Veritas Carbide BurnisherMade in U.S.A.

Item 05K2030, Carbide Burnisher

$14.50

Little and not that expensive

*

If you have a bandsaw or a coping/fret saw

Any shape sanding block that you can cut.

Stick on with rubber cement -double coat-dry-instant stick or Duco or PVA

If Norton 3X/7X/10X sandpaper is avoided or any sandpaper with a nonskid back coating

Amazon

Gaiam Cork Yoga Brick –

$12.89

Peachtree Woodworking Supply Inc. , Atlanta, GA

Fulton 7 Piece Mini Scraper Set

This scraper set is designed to be used for fine, detailed workpieces. Great for smoothing between lacquer applications on curved pieces and restoration work where small detail work is needed.

Scraper sizes:

1-1/8" x 1-3/4"

1-9/16" x 2-11/32"

1-1/16" x 1-27/32"

1-5/16" x 2-5/32"

2-1/16" x 1-3/4"

2-3/8" x 2-5/32"

4-5/16" x 1-5/16"

1757 7 Piece Mini Scraper Set

$24.99

There are luthiers supply sites selling these for about twice the price.

*

StewMac Ultimate Scraper Mini

Item # 103470 In stock, ready to ship!

$34.49

*

Lee Valley Tools Ltd.

Veritas Carbide BurnisherMade in U.S.A.

Item 05K2030, Carbide Burnisher

$14.50

Little and not that expensive

*

If you have a bandsaw or a coping/fret saw

Any shape sanding block that you can cut.

Stick on with rubber cement -double coat-dry-instant stick or Duco or PVA

If Norton 3X/7X/10X sandpaper is avoided or any sandpaper with a nonskid back coating

Amazon

Gaiam Cork Yoga Brick –

$12.89

Last edited:

Cute mini scraper set, although a bit rich for my taste. I'm a penny-pincher. I make my own from time to time from the blades of old saws I pick up at garage sales. I do have five or six Sandvik store-boughten ones, though. They've all paid for themselves many times over with what I've saved in sandpaper using them.

Is there any notification or sign on the sandpapers that they are steareted or not. One can make a choice between suitable for wood or metal and different grain sizes. I suggest the for wood recommended sandpapers are all stearated.The trouble with abrasives (not made of sand these days) is that people think they are for removing material.

There is good advice above, and my two penn’orth is that you should be aiming to cut timber to size rather than abrade it. That way, you get corners where you should have them, and you work to tighter tolerances.

Then, if you have to use an abrasive, you always, always use it on a block. Not doing so means you round off those corners, the ends of planks, the edges of planks, and so forth. Make up a series of ply or mdf ‘fingers’ and glue abrasives to them. Glue a slightly oversize bit of abrasive, then cut to size with a scalpel so you have a crisp corner.

For added sophistication you make up a shooting board so that you can use a block mounted abrasive as a precision dimensioning tool.

Your choice of medium also matters. There are hundreds of abrasives out there, using all manner of materials as grit, and all sorts of substrate. Just as there are different edge tools for wood and metal, so there are different abrasives. Some will clog more easily than others, some will cut better in wood than others, and, to be honest, some you can find in shops/supply houses more easily than others. For myself, I’ve settled on a stearated paper as my ‘stock’ and I buy it in rolls in grits from 80 to 400, with 240 and 320 being most used for models. 400 and beyond is generally for finishing and polishing. (And sharpening)

Allan mentioned scrapers' and he is SO right. But look up cabinet scrapers and how to sharpen them and turn a burr, then apply that to a miniature scraper you make about a half inch or 10mm wide. Just the thing for .decks. You can produce a profile with a file for, say a convex, ,or concave, curve on the hull too, and you end up with a clear grain from the tool finish that will take french polish and dazzle the onlooker with the chatoyance. Compared with which sanding leaves a muddier look under varnish.

But then, paint and green growths and barnacles under the waterline is the way to go, with weathering above the water.

J

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2024

- Messages

- 178

- Points

- 78

Good question, and surprisingly difficult to provide an answer.Is there any notification or sign on the sandpapers that they are steareted or not.

I’ll skirt round it a little by suggesting that you do some research.

First - what brands are available to you? Not all varieties are in all countries.

Then look at manufacturers sites, and their claims and suggestions for different materials and how they cut. When you know about what there is, and what they do, then you can buy some test packs, and see if they live up to the hype.

As regards stearated, they all seem to be light grey in colour, (Mirka) whereas Norton blue is an excellent and long life abrasive. Bear in mind though, that the backing material can also be crucial. The same abrasive, say aluminium oxide, cam be on standard, paper backed sheets, on a 50 foot roll of 4 inch paper backed, maybe made up for machinery such as belt sanders, with a really tough backing that will flex around the drum, (but this is often too inflexible for our purposes)

Aluminium oxide blunts quickly, but is sharp, and is effective, but short lived (for me at least)

This is a big topic. We need to collect together more data and experiences.

Jim