- Joined

- Oct 22, 2018

- Messages

- 150

- Points

- 253

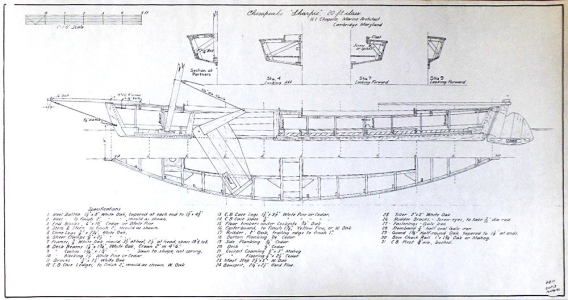

For a commercial boat to gain popularity and become widely used, it must be adaptable to a variety of weather and sailing conditions and present some outstanding economic advantages over any other craft that might be used in the same occupation. In general, flat-bottomed rowing and sailing vessels were the most widely used in North America. One of these, the Sharpie, proved particularly well-suited to oyster fishing, and during the last four decades of the 19th century its use spread along the Atlantic coast of North America as new oyster fisheries and markets opened. The refinements that distinguished the Sharpie from other flat-bottomed skiffs first appeared on some boats built in New Haven, Connecticut, in the late 1840s. These vessels were built for use in the then-important New Haven oyster fishery, which was carried out, for the most part, by hand-clamping in shallow water.

Originally, oysters were harvested by the Powhatan, or settlers, who went into the water and collected them from oyster beds near the shore. However, as the number of people consuming them increased, boats were used to collect them from the beds further away from the rivers and bay. For this purpose, "hand tongs" were developed to collect the oysters with the boat, a long tool similar to a large pair of pincers with metal rakes at the ends. The boatman, standing on the side of the boat, lowered the open tongs into the water until they reached the bottom. He then closed the tongs, capturing the oysters between the rakes. He then raised the tongs to the boat and poured the oysters into the water. The boats operated in waters 15 feet or more deep, so the tongs were very long, heavy, and unwieldy.

The development of the New Haven Sharpie was rapid, and by 1880 it had taken its final form in terms of hull shape, rigging, and size. Although some changes were made later, they were in minor details, such as the finish and small fittings.

The New Haven sharpie was built in two sizes for oyster fishing. One carried 75 to 100 bushels of oysters and was 7.9 to 8.5 m (25 to 28 ft) long; the other carried 150 to 175 bushels and was about 10.6 m (35 ft) long. The smaller sharpie was usually rigged with a single mast and sail, while the larger boat, which usually had two masts, had three mastheads. In the summer, both masts were rigged, the foremast forward and the mainmast aft of the centerboard box, but in winter, or in stormy weather, it was common to leave the mainmast ashore and wedge the foremast into a center vent forward of the centerboard box, thus balancing the rig and operating with only one mast and sail. The New Haven Sharpie, which was long, narrow, and had a low freeboard, was equipped with a folding centerboard. The flat hull had enough upward curvature toward the bow and stern so that, if the boat wasn't carrying much weight, the heel of its straight, upright bow would be an inch or two above the water.

The two working masts of a 10.6 m (35 ft) Sharpie were made of white pine and ranged in diameter from 11.5 to 12.5 cm (4.5 to 5 in) at the deck and 5 cm (2 in) at the top, with a length ranging from 7.9 to 11 m (25 to 36 ft). Instead of booms, they used spars or poles measuring 5.5 to 6 m (18 to 20 ft) that were heeled with tackle attached to the masts and held in loops at the clews of the sails. The tenons at the foot of the masts that rested in the mast-steps were rounded and had brass rings nailed or screwed into them, while similar rings were attached to the mast-step. These rings acted as bearings on which the mast could rotate. The clews were also specially greased for this purpose.

The masts were flexible enough at the top to bend in gusts of wind, and in extreme conditions, they were even designed to break, a significant possibility in a vessel susceptible to capsizing. On most sharpies, the sails, which were hoisted with single-sheave blocks attached to the mastheads, were secured to the luff with wooden or metal mast rings. On early sharpies, the reefing head, which ran parallel to the mast, carried a series of cleats that, passing through fairleads in the luff-rope and descending to the foot of the mast, allowed the sail to be reduced without having to lower the sail. On later models, this system disappeared, and the sails usually had two reefing heads. To reef them, the sail had to be lowered and each reefing head tied while being hoisted.

Because there was no standing rigging and the masts rotated, the sheets could be let out when the boat was sailing downwind, so that the sails would swing forward. In this way, the rig's power could be reduced without reefing or furling. Sometimes, when the wind was light, oystering was done by tongs while the boat moved slowly downwind with the sails billowing. The fisherman, standing on the side deck or stern, could tong or "cut" oysters from a thin bed without having to stop the sharpie. The vessel's unstayed masts were flexible and in bad weather shed some wind, relieving the heeling moment of the sails to some extent. The speed of the long, slender New Haven Sharpie quickly caught the attention of sailors, and these boats were soon converted into yachts or purpose-built as such, giving rise to an entire family of sport and racing boats.

Model Features

• Length: 110 mm

• Beam: 24 mm

• Scale: 1:96

Originally, oysters were harvested by the Powhatan, or settlers, who went into the water and collected them from oyster beds near the shore. However, as the number of people consuming them increased, boats were used to collect them from the beds further away from the rivers and bay. For this purpose, "hand tongs" were developed to collect the oysters with the boat, a long tool similar to a large pair of pincers with metal rakes at the ends. The boatman, standing on the side of the boat, lowered the open tongs into the water until they reached the bottom. He then closed the tongs, capturing the oysters between the rakes. He then raised the tongs to the boat and poured the oysters into the water. The boats operated in waters 15 feet or more deep, so the tongs were very long, heavy, and unwieldy.

The development of the New Haven Sharpie was rapid, and by 1880 it had taken its final form in terms of hull shape, rigging, and size. Although some changes were made later, they were in minor details, such as the finish and small fittings.

The New Haven sharpie was built in two sizes for oyster fishing. One carried 75 to 100 bushels of oysters and was 7.9 to 8.5 m (25 to 28 ft) long; the other carried 150 to 175 bushels and was about 10.6 m (35 ft) long. The smaller sharpie was usually rigged with a single mast and sail, while the larger boat, which usually had two masts, had three mastheads. In the summer, both masts were rigged, the foremast forward and the mainmast aft of the centerboard box, but in winter, or in stormy weather, it was common to leave the mainmast ashore and wedge the foremast into a center vent forward of the centerboard box, thus balancing the rig and operating with only one mast and sail. The New Haven Sharpie, which was long, narrow, and had a low freeboard, was equipped with a folding centerboard. The flat hull had enough upward curvature toward the bow and stern so that, if the boat wasn't carrying much weight, the heel of its straight, upright bow would be an inch or two above the water.

The two working masts of a 10.6 m (35 ft) Sharpie were made of white pine and ranged in diameter from 11.5 to 12.5 cm (4.5 to 5 in) at the deck and 5 cm (2 in) at the top, with a length ranging from 7.9 to 11 m (25 to 36 ft). Instead of booms, they used spars or poles measuring 5.5 to 6 m (18 to 20 ft) that were heeled with tackle attached to the masts and held in loops at the clews of the sails. The tenons at the foot of the masts that rested in the mast-steps were rounded and had brass rings nailed or screwed into them, while similar rings were attached to the mast-step. These rings acted as bearings on which the mast could rotate. The clews were also specially greased for this purpose.

The masts were flexible enough at the top to bend in gusts of wind, and in extreme conditions, they were even designed to break, a significant possibility in a vessel susceptible to capsizing. On most sharpies, the sails, which were hoisted with single-sheave blocks attached to the mastheads, were secured to the luff with wooden or metal mast rings. On early sharpies, the reefing head, which ran parallel to the mast, carried a series of cleats that, passing through fairleads in the luff-rope and descending to the foot of the mast, allowed the sail to be reduced without having to lower the sail. On later models, this system disappeared, and the sails usually had two reefing heads. To reef them, the sail had to be lowered and each reefing head tied while being hoisted.

Because there was no standing rigging and the masts rotated, the sheets could be let out when the boat was sailing downwind, so that the sails would swing forward. In this way, the rig's power could be reduced without reefing or furling. Sometimes, when the wind was light, oystering was done by tongs while the boat moved slowly downwind with the sails billowing. The fisherman, standing on the side deck or stern, could tong or "cut" oysters from a thin bed without having to stop the sharpie. The vessel's unstayed masts were flexible and in bad weather shed some wind, relieving the heeling moment of the sails to some extent. The speed of the long, slender New Haven Sharpie quickly caught the attention of sailors, and these boats were soon converted into yachts or purpose-built as such, giving rise to an entire family of sport and racing boats.

Model Features

• Length: 110 mm

• Beam: 24 mm

• Scale: 1:96