Hello all:

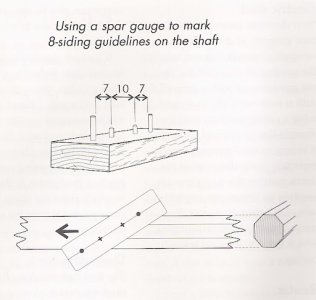

I am working on the yards and spars for my 1:64 “Granado” (Victory Models) and I’m at the stage where I have a few yards that require an Octagonal profile on dowels (8mm and 6mm.) Before I dive in based on my suspicions, I am interested in learning what techniques have worked - or not - for other modellers.

For context, I am largely working with basic hand tools. I do have a tabletop vise at my disposal.

Any and all guidance (or thread redirection) appreciated at this end.

I am working on the yards and spars for my 1:64 “Granado” (Victory Models) and I’m at the stage where I have a few yards that require an Octagonal profile on dowels (8mm and 6mm.) Before I dive in based on my suspicions, I am interested in learning what techniques have worked - or not - for other modellers.

For context, I am largely working with basic hand tools. I do have a tabletop vise at my disposal.

Any and all guidance (or thread redirection) appreciated at this end.