- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

Hello Dear Friends

Some time ago, @rtibbs Ron asked me for my postal address. Tonight, when the Admiral returned home after work, she handed me a parcel that came from the Netherlands. I am always super-excited when I receive something from the Netherlands, but this time it was different as I had no idea what was in the parcel. Can you imagine my feelings when I opened the parcel and found this inside?

@Uwek subsequently asked me for a book review and here it is:

Publishers: Verloren

Pages: 128

Price: € 47

ISBN/ISSN: 90-6550-772-8

Included CD-Rom and Build Plans

This particular copy was acquired from antiquarian Gertjan Bestebreurtje in the Netherlands.

REVIEW: Cristel R. Stolk

@Ab Hoving Ab Hoving – former Head of Restoration in the Department of Dutch History of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, earlier authored the book entitled De schepen van Abel Tasman (Hilversum, Verloren, 2000). In this publication he reported on his findings on the construction methods and processes of two famous ships which formed part of Tasman’s expedition – the jaght “Heemskerck” and the Fluit, “Zeehaen” both of which were built in approximately 1640.

Based on diverse sources of 17th century shipbuilding techniques, Hoving analyzed both ships and created exact scale models of each. Hoving’s build plans are included in the publication in both paper and digital (CD-Rom) versions, which enables the reader and model shipbuilder to create their own accurate scale models. This concept proved so successful that it was decided to extend the subject matter to that of the expedition ship of Willem Barentsz.

The story of Barentsz’s expedition is well known to most Dutch people. In an effort to reach Asia via a different route to the one around the Cape of Good Hope, a new and as yet untraveled route along the North Pole was conceived. Two earlier attempts to navigate this route, both failed. On xxx 1596, Barentsz, who was also in charge of both previous expeditions, left Amsterdam with two ships in what was to be a third and final attempt.

Even though the third trip started off in a more promising fashion than the previous two, the expedition is once again halted by pack-ice. While the one ship under the command of Jan Corneliszoon Rijp explored a northwesterly route, the ship of Willem Barentsz under the command of Jacob van Heemskerck, set off in a northeasterly direction. Ultimately the latter is stranded at Nova Zembla where the men are forced to over-winter.

After spending the barren and desolate winter in a self-constructed, wooden Safe House (Het Behouden Huys), the surviving crew members set off in the ship’s life boats (sloops) for Russia. The enormous pressure of the pack-ice had meanwhile rendered the actual ship of Barentsz unusable. Willem Barents though, was mot destined to witness the arrival in Russia and the men’s subsequent return to the Netherlands. He died before the sloops could reach Russia.

The ship of WB was built 50 years earlier than the vessels of Tasman which made Hoving’s research of its build processes much more difficult than those the two younger ships. First, there are far fewer sources available on shipbuilding in the 16th century than in the 17th. Second, it would have been incorrect to apply the knowledge gained from researching the building methods of ships in the 17th century to those of an earlier era, as new techniques and approaches were implemented at the turn of the century. The reasons for these new techniques and approaches were the results of a booming Dutch trade and the war with Spain. It is important to understand that at this point in history, there was no distinction made between merchant vessels and men-o-war – the majority of ships were built according to the same set of principles and rules.

Hoving based most of his research on two 17th century documents as well as two similar, but shorter and seemingly less comprehensive documents – one dating back to the end of the 16th century and one to the beginning of the 17th century. Furthermore, his research also draws on historical sources and archeological findings. The eyewitness report of one of Barentsz’s crew members, Gerrit de Veer, proved invaluable. Not only does his diary provide valuable and detailed information on the ships used in the expedition, but it is also richly illustrated. Based on the diary, Hoving could conclude that the ship type was that of a jacht of 20-25 meters in length.

From an archeological background, various objects and instruments from the ship were salvaged. Of particular importance was the discovery of a section of the actual hull of the ship which is currently in a museum in Moscow. Based on that and other reconstructions, Hoving could reconstruct the bulkheads/frames (spanten) and the way that the ship’s hull was planked. These findings, in turn, were compared to another important resource: the 1990-discovery of a shipwreck (dated 1593) off the coast of Texel. Lastly, similar reconstructions, such as the well-known Duyfken replica ship, also provided reference material.

Despite all the research, Hoving emphasizes time and time again the fact that his reconstruction is at best a hypothesis. Interestingly, the same research material also led to another model – that of Gerald de Weerdt - previously curator of the museum Het Behouden Huys in Terschelling and now group leader of the reconstruction of the replica ship of WB in Harlingen – which was built following the 400-year Anniversary celebrations.

Hoving does point out some differences between the models – especially the different approaches taken in rigging the ships, but mentions that instead of listing differences, he would much rather choose to focus on the similarities. For the sake of this review, however, I will not delve deeper into the technical aspects and methods of Hoving’s reconstruction – that is after all what the book is for.

For experienced model shipbuilders, and those with a background in historical shipbuilding, the book will be a godsend, although it can be a daunting read for the inexperienced modeler. Part of this is caused by the fact that Hoving often makes references to his earlier works – especially the sections pertaining to the analysis of 17th century shipbuilding and the “shell-first” build technique.

Apart from this observation, the book is a great addition to Maritime History and the section on maritime archeology adds greatly to our existing database. The fact that Hoving presents this information by means of a model which transcends two-dimensional writing into a three-dimensional model, allows him to present his findings in a tangible way.

Even though we cannot say with any degree of certainty that this was indeed what the WB had looked like – new findings and new information might change the picture completely – Hoving makes a compelling case for the current status quo.

“Rowing with oars is still preferable to a wreck on the ocean floor.

(Review: Cristel R. Stolk)

From my side, I would like to add the following information:

The INDEX gives a very good idea of the scope of information covered by the book, but before we get to that let's take a peek inside:

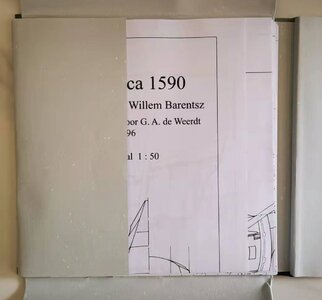

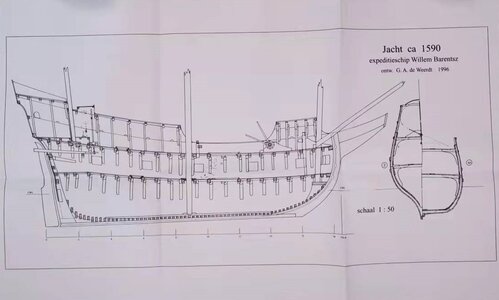

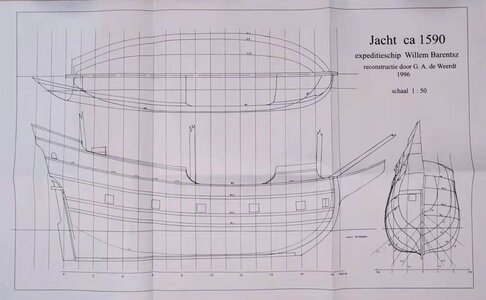

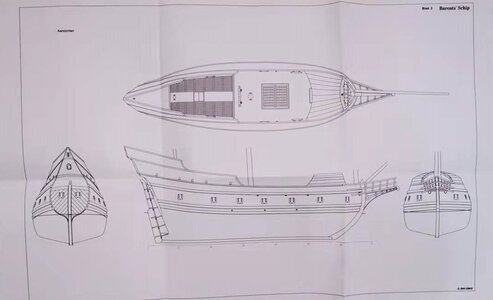

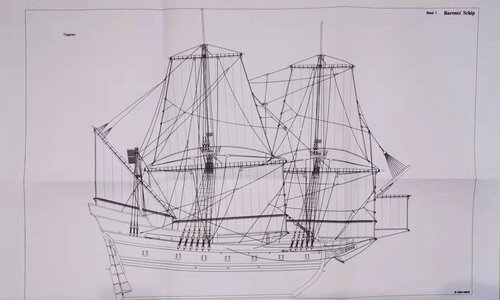

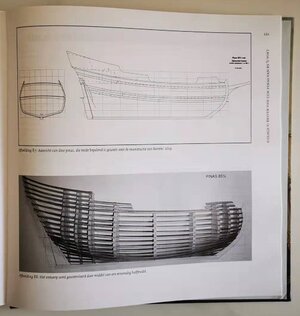

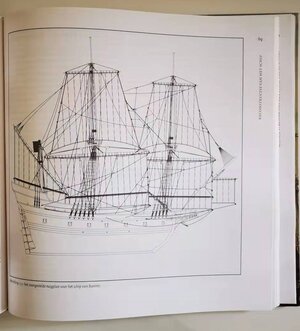

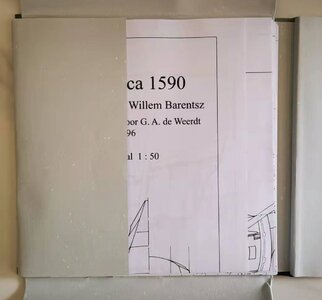

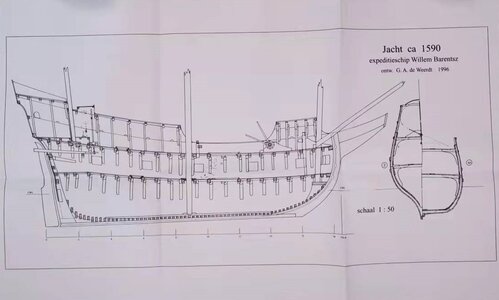

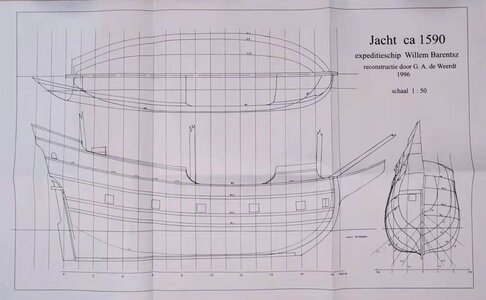

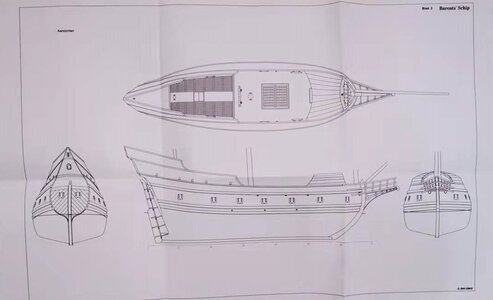

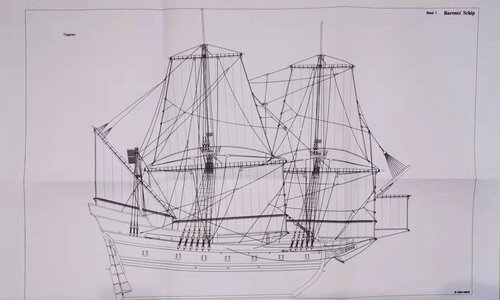

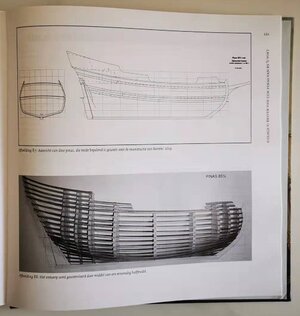

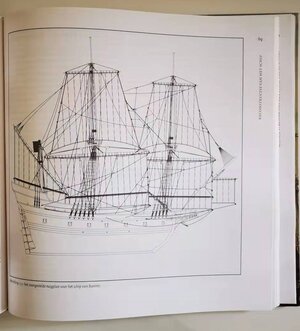

Included in the book are 11 double-printed sheets with construction plans and drawings in scale 1:50. A peek preview of four of these sheets looks as follows:

In conjunction with the supplied CD-Rom, the prospective modeler can print exact copies of these plans in any scale that he desires and they are more than sufficient for the scratch-modeler to construct a model.

A random look at some of the pages:

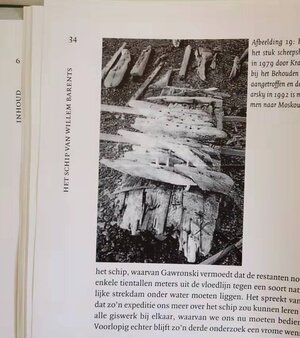

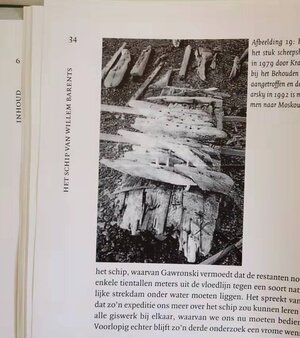

Fragments of the actual hull which are now in a museum in Moscow.

The 85.5 feet Pinas from around 1600, was one of the many aspects analyzed in order to determine the final hull shape of the Willem Barents.

Suggested rigging

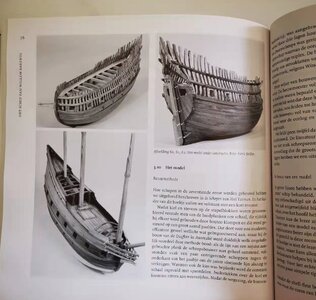

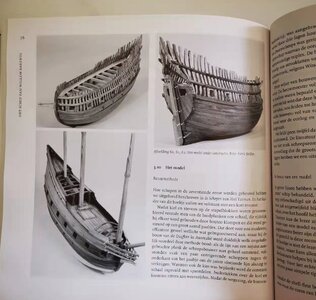

This model was constructed by Ab Hoving following the exact guidelines and methods of the typical Dutch build method of shell-first.

This was what survived of the woollen flag of Amsterdam that was flown from the Willem Barentsz.

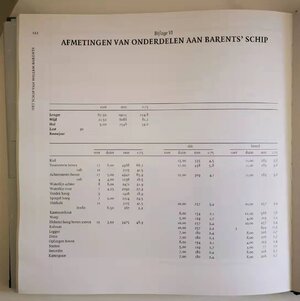

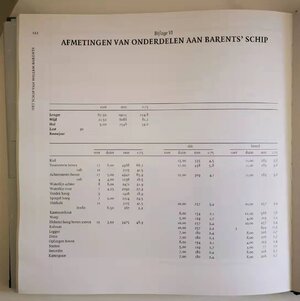

Some of the Tables and Measurements

INDEX

Thanks

Pre-Amble

Introduction

PART I: The trip of Willem Barentsz and Jacob van Heemskerck (Peter Sigmond)

Sources

Addenda:

* De Veer’s Diary;

* Design Brief (Van Dam);

* Data: Measurements, weight and dimensions

*Components’ size in relation to the overall length of the ship

*Design Brief of an 85.5 feet Pinas from 1593 (State Archives – Zeeland)

*Dimensions and components of the Willem Barents

Build Plans

In conclusion I want to say that this is the best gift that I could have received. To anyone interested in Dutch shipbuilding - and then in particular the earlier years - this is an indispensable source of information.

Thank you @rtibbs Ron for the gift and @Ab Hoving who authored this magnificent piece of work!

Heinrich

Some time ago, @rtibbs Ron asked me for my postal address. Tonight, when the Admiral returned home after work, she handed me a parcel that came from the Netherlands. I am always super-excited when I receive something from the Netherlands, but this time it was different as I had no idea what was in the parcel. Can you imagine my feelings when I opened the parcel and found this inside?

@Uwek subsequently asked me for a book review and here it is:

Publishers: Verloren

Pages: 128

Price: € 47

ISBN/ISSN: 90-6550-772-8

Included CD-Rom and Build Plans

This particular copy was acquired from antiquarian Gertjan Bestebreurtje in the Netherlands.

REVIEW: Cristel R. Stolk

@Ab Hoving Ab Hoving – former Head of Restoration in the Department of Dutch History of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, earlier authored the book entitled De schepen van Abel Tasman (Hilversum, Verloren, 2000). In this publication he reported on his findings on the construction methods and processes of two famous ships which formed part of Tasman’s expedition – the jaght “Heemskerck” and the Fluit, “Zeehaen” both of which were built in approximately 1640.

Based on diverse sources of 17th century shipbuilding techniques, Hoving analyzed both ships and created exact scale models of each. Hoving’s build plans are included in the publication in both paper and digital (CD-Rom) versions, which enables the reader and model shipbuilder to create their own accurate scale models. This concept proved so successful that it was decided to extend the subject matter to that of the expedition ship of Willem Barentsz.

The story of Barentsz’s expedition is well known to most Dutch people. In an effort to reach Asia via a different route to the one around the Cape of Good Hope, a new and as yet untraveled route along the North Pole was conceived. Two earlier attempts to navigate this route, both failed. On xxx 1596, Barentsz, who was also in charge of both previous expeditions, left Amsterdam with two ships in what was to be a third and final attempt.

Even though the third trip started off in a more promising fashion than the previous two, the expedition is once again halted by pack-ice. While the one ship under the command of Jan Corneliszoon Rijp explored a northwesterly route, the ship of Willem Barentsz under the command of Jacob van Heemskerck, set off in a northeasterly direction. Ultimately the latter is stranded at Nova Zembla where the men are forced to over-winter.

After spending the barren and desolate winter in a self-constructed, wooden Safe House (Het Behouden Huys), the surviving crew members set off in the ship’s life boats (sloops) for Russia. The enormous pressure of the pack-ice had meanwhile rendered the actual ship of Barentsz unusable. Willem Barents though, was mot destined to witness the arrival in Russia and the men’s subsequent return to the Netherlands. He died before the sloops could reach Russia.

The ship of WB was built 50 years earlier than the vessels of Tasman which made Hoving’s research of its build processes much more difficult than those the two younger ships. First, there are far fewer sources available on shipbuilding in the 16th century than in the 17th. Second, it would have been incorrect to apply the knowledge gained from researching the building methods of ships in the 17th century to those of an earlier era, as new techniques and approaches were implemented at the turn of the century. The reasons for these new techniques and approaches were the results of a booming Dutch trade and the war with Spain. It is important to understand that at this point in history, there was no distinction made between merchant vessels and men-o-war – the majority of ships were built according to the same set of principles and rules.

Hoving based most of his research on two 17th century documents as well as two similar, but shorter and seemingly less comprehensive documents – one dating back to the end of the 16th century and one to the beginning of the 17th century. Furthermore, his research also draws on historical sources and archeological findings. The eyewitness report of one of Barentsz’s crew members, Gerrit de Veer, proved invaluable. Not only does his diary provide valuable and detailed information on the ships used in the expedition, but it is also richly illustrated. Based on the diary, Hoving could conclude that the ship type was that of a jacht of 20-25 meters in length.

From an archeological background, various objects and instruments from the ship were salvaged. Of particular importance was the discovery of a section of the actual hull of the ship which is currently in a museum in Moscow. Based on that and other reconstructions, Hoving could reconstruct the bulkheads/frames (spanten) and the way that the ship’s hull was planked. These findings, in turn, were compared to another important resource: the 1990-discovery of a shipwreck (dated 1593) off the coast of Texel. Lastly, similar reconstructions, such as the well-known Duyfken replica ship, also provided reference material.

Despite all the research, Hoving emphasizes time and time again the fact that his reconstruction is at best a hypothesis. Interestingly, the same research material also led to another model – that of Gerald de Weerdt - previously curator of the museum Het Behouden Huys in Terschelling and now group leader of the reconstruction of the replica ship of WB in Harlingen – which was built following the 400-year Anniversary celebrations.

Hoving does point out some differences between the models – especially the different approaches taken in rigging the ships, but mentions that instead of listing differences, he would much rather choose to focus on the similarities. For the sake of this review, however, I will not delve deeper into the technical aspects and methods of Hoving’s reconstruction – that is after all what the book is for.

For experienced model shipbuilders, and those with a background in historical shipbuilding, the book will be a godsend, although it can be a daunting read for the inexperienced modeler. Part of this is caused by the fact that Hoving often makes references to his earlier works – especially the sections pertaining to the analysis of 17th century shipbuilding and the “shell-first” build technique.

Apart from this observation, the book is a great addition to Maritime History and the section on maritime archeology adds greatly to our existing database. The fact that Hoving presents this information by means of a model which transcends two-dimensional writing into a three-dimensional model, allows him to present his findings in a tangible way.

Even though we cannot say with any degree of certainty that this was indeed what the WB had looked like – new findings and new information might change the picture completely – Hoving makes a compelling case for the current status quo.

“Rowing with oars is still preferable to a wreck on the ocean floor.

(Review: Cristel R. Stolk)

From my side, I would like to add the following information:

The INDEX gives a very good idea of the scope of information covered by the book, but before we get to that let's take a peek inside:

Included in the book are 11 double-printed sheets with construction plans and drawings in scale 1:50. A peek preview of four of these sheets looks as follows:

In conjunction with the supplied CD-Rom, the prospective modeler can print exact copies of these plans in any scale that he desires and they are more than sufficient for the scratch-modeler to construct a model.

A random look at some of the pages:

Fragments of the actual hull which are now in a museum in Moscow.

The 85.5 feet Pinas from around 1600, was one of the many aspects analyzed in order to determine the final hull shape of the Willem Barents.

Suggested rigging

This model was constructed by Ab Hoving following the exact guidelines and methods of the typical Dutch build method of shell-first.

This was what survived of the woollen flag of Amsterdam that was flown from the Willem Barentsz.

Some of the Tables and Measurements

INDEX

Thanks

Pre-Amble

Introduction

PART I: The trip of Willem Barentsz and Jacob van Heemskerck (Peter Sigmond)

- Passage to the East

- The trip

- The Dutch Republic circa 1600

- Introduction

- First Attempts

- Sources for the reconstruction of Barents’s ship

- In search of general characteristics

- Internals – Introduction

- Hull Planking

- Determining the size

- Stability

- Armament

- Reconstruction of the rigging

- Miscellaneous

- Decorations

- The Model

- Sources

- Choices

- A remarkable development in hull shape

- The No 6 Frame

- A trial model

- Upper build

- Interior Build

- Rigging

- Calculations

- Conclusion

- The possibilities of the CD Rom

- PC System Requirements

- Functioning

- Copying the plans

- The View Companion Function

- Tables

Sources

Addenda:

* De Veer’s Diary;

* Design Brief (Van Dam);

* Data: Measurements, weight and dimensions

*Components’ size in relation to the overall length of the ship

*Design Brief of an 85.5 feet Pinas from 1593 (State Archives – Zeeland)

*Dimensions and components of the Willem Barents

Build Plans

In conclusion I want to say that this is the best gift that I could have received. To anyone interested in Dutch shipbuilding - and then in particular the earlier years - this is an indispensable source of information.

Thank you @rtibbs Ron for the gift and @Ab Hoving who authored this magnificent piece of work!

Heinrich

Last edited: