Hi All

I am working on a very simple (1:120 pl;astic) model fo the Endeavour, as my intro to doing ship models properly. I got a simple set of rigging blocks - for clew, lift, sheet and braces only. Because I have no idea what I am doing, I tried to understand and then compare to detailed models to see if I had it right. In doing this I found one (minor) difference between what I found and what I saw on models. I dunno if people are interested but Ithought I would post it here anyway.

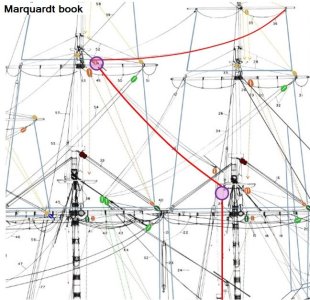

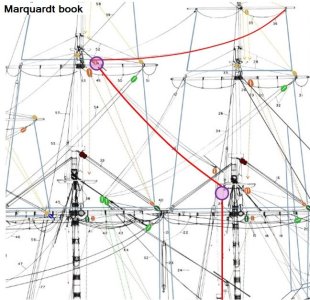

I was trying to figure out the Fore mast Top Gallant braces (I am learning the lingo!) and the diagram in Marquardt's "Anatomy of the Ship" . See attached figures.

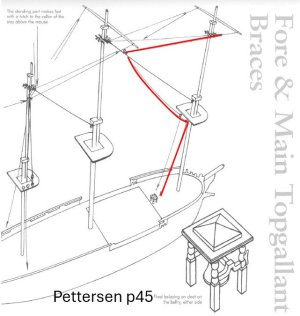

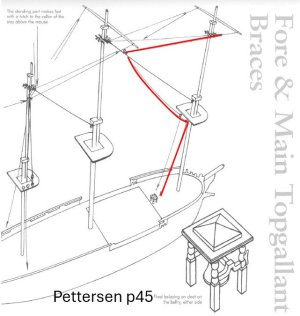

I checked this with Peterrson's book, and it agreed (althoug this book is not specifically The Endeavour).

But when I looked at models on Endeavour online the braces were slightly different...going straight to the deck after passing through the block on the forestay. Again, a picture is attached.

I guess ships canbe rigged in slightly different ways at different times? Anyway, I checked with the Master ofr the Endeavor replica in Sydney and he confirmed the rigging as being what is in the Marquardt and Peterrson books.

I think I saw the same thing in the Main Top Gallant too. BUt I need to check,. I think I saw it somewhere else, in any event.

So...just for those who are pedantic or can explain why it might be rigged differently at different time?

Thanks!

John L

I am working on a very simple (1:120 pl;astic) model fo the Endeavour, as my intro to doing ship models properly. I got a simple set of rigging blocks - for clew, lift, sheet and braces only. Because I have no idea what I am doing, I tried to understand and then compare to detailed models to see if I had it right. In doing this I found one (minor) difference between what I found and what I saw on models. I dunno if people are interested but Ithought I would post it here anyway.

I was trying to figure out the Fore mast Top Gallant braces (I am learning the lingo!) and the diagram in Marquardt's "Anatomy of the Ship" . See attached figures.

I checked this with Peterrson's book, and it agreed (althoug this book is not specifically The Endeavour).

But when I looked at models on Endeavour online the braces were slightly different...going straight to the deck after passing through the block on the forestay. Again, a picture is attached.

I guess ships canbe rigged in slightly different ways at different times? Anyway, I checked with the Master ofr the Endeavor replica in Sydney and he confirmed the rigging as being what is in the Marquardt and Peterrson books.

I think I saw the same thing in the Main Top Gallant too. BUt I need to check,. I think I saw it somewhere else, in any event.

So...just for those who are pedantic or can explain why it might be rigged differently at different time?

Thanks!

John L

) but Marquardt and Petterson were my main references. This is my first ship model and it is a 1:120 bad plastic model (with many errors - eg shrouds on mizzen mast foul the railings on the side of the ship! A terrible error! But as a learning experience it has been good...)

) but Marquardt and Petterson were my main references. This is my first ship model and it is a 1:120 bad plastic model (with many errors - eg shrouds on mizzen mast foul the railings on the side of the ship! A terrible error! But as a learning experience it has been good...)