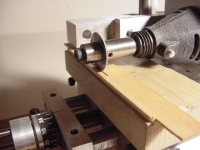

They have these attachments on Amazon at varying prices.Truth be told, that sounds like what you need isn't an X-Y table, so much as a lathe with a decent taper attachment (or a tailstock that you can move from side to side, although that's a royal pain to set up.) Turn the round sections to the desired length and taper, leaving the sections to be squared standing proud. The take the spar and mill the flats as required. Actually, once you've turned the round tapered sections, you can work the flats with a decent hand plane very easily. You might want to mount a plate or piece of wood to the side of your plane to ensure 90-degree angles, or whatever other angle you desire.

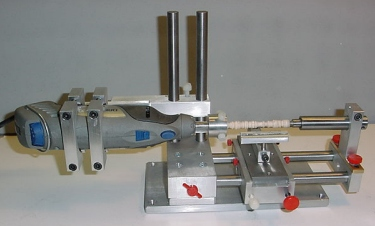

If you have access to a machinist's lathe with a #2 Morse taper in the tailstock, the below offsetting taper turning device is worth its weight in gold: https://www.ebay.com/itm/176398188759 About $70.00 on eBay.

View attachment 520756

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

X, Y Milling table use

- Thread starter Ted Robinson

- Start date

- Watchers 12

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2024

- Messages

- 160

- Points

- 78

I have a lot of 3mm and 4mm spars to make in addition to 6.5mm masts.

The materials provided are 8.5mmdowels for the mast and 6mm for the spars.

I want to milk these close to size.

Some of the masts have squared ends and some spars have to be octagonal in the centers.

That’d a really good task to add some accuracy into.

But in those sizes, and tapered, it’s a big ask.

However, it’s an everyday requirement when making, say, fly fishing rods, so why not adapt that type of solution?

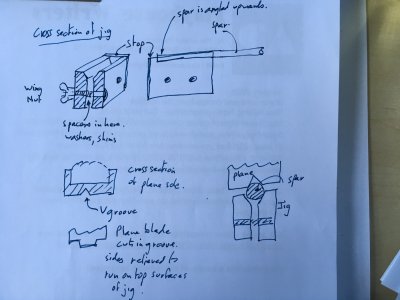

First off, find or allocate a No60 ½ block plane, look for a decent old one, made by Stanley or Record or another good maker. If you have milling machine, mill a lengthwise V groove the length of the sole using a cutter canted 45 degrees or your choice of alternative, such as mounting the plane on the crossslide and the cutter in the lathe chuck.

You now have a plane which will self guide itself down the length of a spar producing an even chamfer. By starting with a square section you can easily make it octagonal in 4 passes.

Now we deal with the taper.

Imagine a long open topped box, with the sides adjustable so that they can move to be narrower at one end than the other. That’s what we need. The top, inner corners, are chamfered enough to allow a spar blank to sit there. A stop is an across the far end.

Place your blank in the adjustable groove, and open one end enough to let the spar sit down at its narrow end.

Run your plane along it. It will stop cutting when it has done enough. Turn the spar and repeat until happy.

Here, I’ll try sketching it.

The jig portion is held in a vice on the workbench. Adjust with shims until the degree of spar material you need to remove is showing. then use your grooved plane to remove the excess. Because the spar is supported along its full length, it should be distortion free. Your plane blade will be about surgically sharp, using the ScarSharp method or whatever, and if set for a light cut, should manage against any grain run out.

I have a device of this type on a much larger scale, and this is on the list of items to make once the masts are in place.

Apologies for the poor quality sketch. I'm around for further questions.

Jim

- Joined

- Oct 1, 2023

- Messages

- 1,900

- Points

- 488

I would love to get a lathe, milling machine and sander but don't have the room.They have these attachments on Amazon at varying prices.

I gave up my second bedroom, where I was setting up shop, to my handicapped step daughter who was struggling living on her own. I now work off a table in my bedroom since I was banished from the living room by the Commendant and her Lieutenant. That's a joke.

Thank you for the details. I'm going to get some wood t make a v groove firstThat’d a really good task to add some accuracy into.

But in those sizes, and tapered, it’s a big ask.

However, it’s an everyday requirement when making, say, fly fishing rods, so why not adapt that type of solution?

First off, find or allocate a No60 ½ block plane, look for a decent old one, made by Stanley or Record or another good maker. If you have milling machine, mill a lengthwise V groove the length of the sole using a cutter canted 45 degrees or your choice of alternative, such as mounting the plane on the crossslide and the cutter in the lathe chuck.

You now have a plane which will self guide itself down the length of a spar producing an even chamfer. By starting with a square section you can easily make it octagonal in 4 passes.

Now we deal with the taper.

Imagine a long open topped box, with the sides adjustable so that they can move to be narrower at one end than the other. That’s what we need. The top, inner corners, are chamfered enough to allow a spar blank to sit there. A stop is an across the far end.

Place your blank in the adjustable groove, and open one end enough to let the spar sit down at its narrow end.

Run your plane along it. It will stop cutting when it has done enough. Turn the spar and repeat until happy.

Here, I’ll try sketching it.

View attachment 520889

The jig portion is held in a vice on the workbench. Adjust with shims until the degree of spar material you need to remove is showing. then use your grooved plane to remove the excess. Because the spar is supported along its full length, it should be distortion free. Your plane blade will be about surgically sharp, using the ScarSharp method or whatever, and if set for a light cut, should manage against any grain run out.

I have a device of this type on a much larger scale, and this is on the list of items to make once the masts are in place.

Apologies for the poor quality sketch. I'm around for further questions.

Jim

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2024

- Messages

- 160

- Points

- 78

My daughter is disabled. I understand your situation.

So the compound table is going to do duty as an accurate vice? Right, we're off and running. Roger was correct in talking about V blocks. What I was trying to describe was in effect an elongated V block, equipped with the means of altering it to widen the fee at one end. By guiding a sharp plane along the horizontal, you have a taper.

Alternatively scratch stocks could be your friends here. using a profile of about a 1/3 circle, they can refine small material into being circular, though a bit fiddly. Back to the elongated v block - equipped with a sacrificial top running surface (PTFE tape might work) you can produce the tapper you need.

Only you can say how accurate you want the dimensions to be. The naked eye isn't too good at distinguishing between a scale 12" diameter or 18" diameter at the end of a spar, as long as it looks thinner than the centre.

J

So the compound table is going to do duty as an accurate vice? Right, we're off and running. Roger was correct in talking about V blocks. What I was trying to describe was in effect an elongated V block, equipped with the means of altering it to widen the fee at one end. By guiding a sharp plane along the horizontal, you have a taper.

Alternatively scratch stocks could be your friends here. using a profile of about a 1/3 circle, they can refine small material into being circular, though a bit fiddly. Back to the elongated v block - equipped with a sacrificial top running surface (PTFE tape might work) you can produce the tapper you need.

Only you can say how accurate you want the dimensions to be. The naked eye isn't too good at distinguishing between a scale 12" diameter or 18" diameter at the end of a spar, as long as it looks thinner than the centre.

J

- Joined

- Dec 7, 2022

- Messages

- 28

- Points

- 58

I have no lathe and a much less equipped work shop than most of the fine craftsmen on this site. I had to taper a 1/4” dowel for the mast on the Billings’ African Queen. I started a small taper on the end by sanding and clamped the other end in an ordinary hand held drill. Using a drill gauge clamped to my work table as a draw bar, I pushed the rotating dowel through progressively smaller holes by progressively shorter distances to achieve the taper I wanted. This means I had a stepped dowel but using sandpaper on the rotating dowel, I smoothed the steps to a genuine taper. This works with a soft wood. I had used a drill gauge that measures fractions of an inch but had I used a drill gauge that measures numbered drill bits I would have gotten an even smoother step taper as the the hole sizes are in smaller incremental steps.

- Joined

- Apr 11, 2022

- Messages

- 18

- Points

- 48

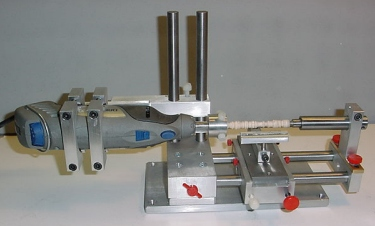

I agree. There's nothing more discouraging than struggling with inferior tools. This not only applies to precision mechanical and/or power tools but hand tools al well.Get a decent vise....and if you plan on milling round pieces, a rotary clamp ( dividing attachment) helps....but you can just use mechanical clamps (stepping blocks)View attachment 520629View attachment 520630View attachment 520624View attachment 520623

For those who for reasons of space or budget don't have a large collection of stationary power tools, I would suggest they take a look at the Vanda-Lay Industries product line. See: https://vanda-layindustries.com/ Note that their machines are upgradable. You could start with a micro drill press and then upgrade that to their Acra-mill by adding optional parts packages.

Vanda-Lay offers model making drill presses, lathes, and milling machines, as well as a thickness sander, powered by a common Dremel moto tool or, if you wish, a Foredom flex-shaft handpiece. These machines are very well made of CNC cut aluminum and stainless steel and are very reasonably priced. They aren't super powerful, owing to the limitations of their power sources, but are entirely suitable for ship modeling and are the most compact machines of their type on the market.

Vanda-Lay drill press. USD $140. (Shown without Dremel moto tool mounted.)

Vanda-Lay "Acra Mill" USD $225. Note Dremel tool for overall size.

Vanda-Lay Acra Mill set up for table sawing:

Acra Mill set up for thickness sanding:

12" Mini-lathe attachment for Acra MIll. USD $60.

Vanda-Lay offers model making drill presses, lathes, and milling machines, as well as a thickness sander, powered by a common Dremel moto tool or, if you wish, a Foredom flex-shaft handpiece. These machines are very well made of CNC cut aluminum and stainless steel and are very reasonably priced. They aren't super powerful, owing to the limitations of their power sources, but are entirely suitable for ship modeling and are the most compact machines of their type on the market.

Vanda-Lay drill press. USD $140. (Shown without Dremel moto tool mounted.)

Vanda-Lay "Acra Mill" USD $225. Note Dremel tool for overall size.

Vanda-Lay Acra Mill set up for table sawing:

Acra Mill set up for thickness sanding:

12" Mini-lathe attachment for Acra MIll. USD $60.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2024

- Messages

- 160

- Points

- 78

Setting up a machine shop is well and good, and I have machines that make the lights dim when turned on, but...

The thing about machines is that they all need care and maintenance, and attention devoted to setting up, and learning how best to set about basics. Alby Snowdon's Pinnace for HMS Venerable (See thread) arrived after some months of learning to use CAD/CAM/CNC software and machines for the frames.

The thing about making a model off the plans, by hand, with nothing but eye and sharp tools, is the degree of satisfaction in making something, all by yourself. As with the original boatbuilders, fairing the shapes and sizes by eye and by measure results in a good looking model, though it may not be quite accurate. But then, we regularly talk about sanding down the planking to fair it for the final shell, so absolute accuracy is sacrificed in pursuit of simplicity. How do we know that the bulkheads in a kit are entirely accurate? we abdicate that responsibility to the kit maker. Come to that, how many actual ships were accurate to their drawings - entirely accurate? Builders faced with shortages or slightly unsuitable materials may well have made changes at the construction stage. So so may we.

I'm just saying that with a saw, a scalpel, a drawing, some timber and a vernier gauge, you can learn enough hand skill to get by without a full stable of machines, and enjoy greater satisfaction as a result.

A tapered yard? - make some u shape templates to size for each inch along the length, and steadily work down the timber with blades, a miniature plane, and abrasive. Certainly it takes time, but it is extremely satisfying to have done so.

Jim

The thing about machines is that they all need care and maintenance, and attention devoted to setting up, and learning how best to set about basics. Alby Snowdon's Pinnace for HMS Venerable (See thread) arrived after some months of learning to use CAD/CAM/CNC software and machines for the frames.

The thing about making a model off the plans, by hand, with nothing but eye and sharp tools, is the degree of satisfaction in making something, all by yourself. As with the original boatbuilders, fairing the shapes and sizes by eye and by measure results in a good looking model, though it may not be quite accurate. But then, we regularly talk about sanding down the planking to fair it for the final shell, so absolute accuracy is sacrificed in pursuit of simplicity. How do we know that the bulkheads in a kit are entirely accurate? we abdicate that responsibility to the kit maker. Come to that, how many actual ships were accurate to their drawings - entirely accurate? Builders faced with shortages or slightly unsuitable materials may well have made changes at the construction stage. So so may we.

I'm just saying that with a saw, a scalpel, a drawing, some timber and a vernier gauge, you can learn enough hand skill to get by without a full stable of machines, and enjoy greater satisfaction as a result.

A tapered yard? - make some u shape templates to size for each inch along the length, and steadily work down the timber with blades, a miniature plane, and abrasive. Certainly it takes time, but it is extremely satisfying to have done so.

Jim