I admit it was intimidating for me going from plastic ships to wooden. You go from “putting together” to “building” and shaping wood. I have made many mistakes in my wooden adventures. Mostly from not looking far enough ahead in the process to catch problems ahead of time. I have made terrible rigging mistakes as well.

Reading, studying, and research on the internet and YouTube does wonders.

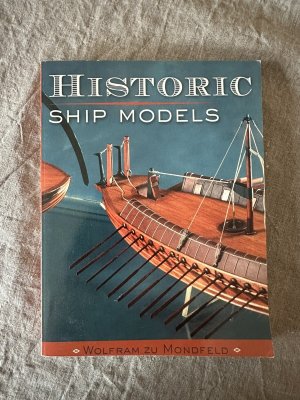

One of the main books I always turn to is this book

Reading, studying, and research on the internet and YouTube does wonders.

One of the main books I always turn to is this book