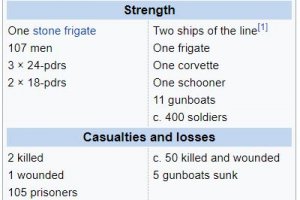

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

31 May 1805 - Bombardment of "HMS Diamond Rock" commenced.

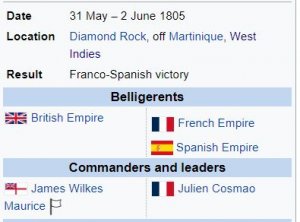

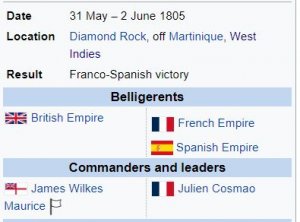

The Battle of Diamond Rock took place between 31 May and 2 June 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars.

The Battle of Diamond Rock took place between 31 May and 2 June 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars. It was an attempt by Franco-Spanish force despatched under Captain Julien Cosmao to retake Diamond Rock, at the entrance to the bay leading to Fort-de-France, from the British forces that had occupied it over a year before.

The French in Martinique had been unable to oust the defenders from the strategically important rock, and the British garrison was able to control access to Fort-de-France Bay, firing on ships attempting to enter it with guns they had placed on the cliffs. The arrival of a large combined Franco-Spanish fleet in May changed the strategic situation. The French commander, Pierre de Villeneuve, had vague orders to attack British possessions in the Caribbean, but instead waited at Martinique for clearer instructions. He was finally persuaded to authorise an assault on the British position, and a Franco-Spanish flotilla was despatched to storm the rock. Already short of water, the defenders held on in the summit for several days, while the French, who had neglected to bring scaling ladders, could make little headway.

The British, short of both water and ammunition, eventually negotiated the surrender of the rock after several days under fire. As Diamond Rock was legally considered a Royal Navy vessel, and the commander was legally "captain" of it, after repatriation, he was tried by court-martial (as the law dictated in any case where a captain loses his ship, regardless of the cause), but was honourably acquitted.

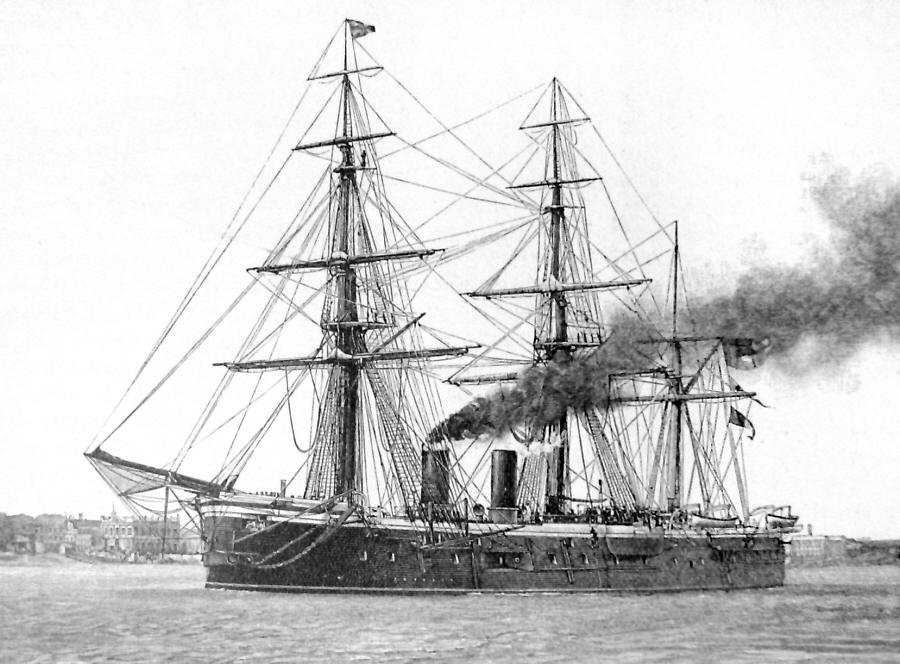

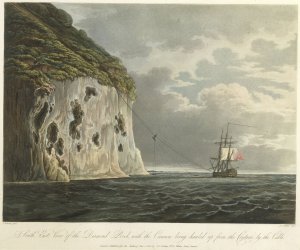

The Franco-Spanish combined fleet under Captain Cosmao attacking Diamond Rock, by Auguste Mayer

Background

Diamond Rock is fortified

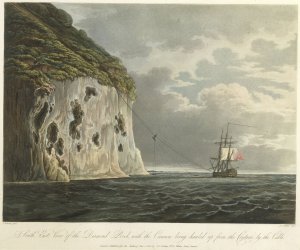

Diamond Rock had been fortified in January 1804 on the orders of Commodore Samuel Hood. Hood had been active in the West Indies, protecting British convoys from French privateers issuing out of the two major naval bases the French retained in the Caribbean, at Guadeloupe and Martinique. The privateers had captured a number of valuable cargoes and were diverting British warships to protect the merchant fleets. Hood decided to blockade Martinique, and thus curtail the privateers and intercept supplies destined for the French garrison. Patrolling off the bay at the southern end of the island, in which one of Martinique's two main ports, Fort-de-France, was located, Hood saw that if Diamond Rock could be occupied, it would allow the British to effectively control the shipping approaching the ports on the western side, as the currents around the island made the easiest approaches mean passing within sight of Diamond Rock.

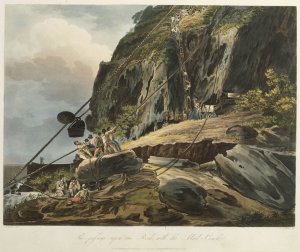

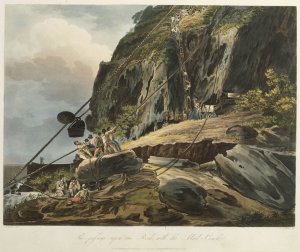

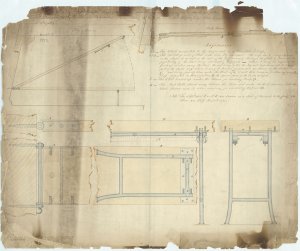

A cannon is hauled up to the summit of the rock suspended by a cable lashed to the base of Centaur's mainmast

Hood reconnoitered Diamond Rock and considered it excellently defensible, with the only possible landing site being on the western side. He wrote that 'thirty riflemen will keep the hill against ten thousand ... it is a perfect naval post.' A party of men were landed on 7 January 1804, from Hood's flagship HMS Centaur, under the command of Centaur's first lieutenant James Wilkes Maurice. They promptly fortified the small cove they had landed at with their launch's 24-pounder, and established forges and artificers' workshops in a cave at the base of the rock. After fixing ladders and ropes to scale the sheer sides of the rock, they were able to access the summit and began to establish messes and sleeping areas in a number of small caves. Bats were driven out by burning bales of hay, and a space was cleared by blasting at the top of the rock in order to establish a battery. In February a number of guns were transferred over from Centaur, with two 24-pounders being installed in a cave near sea level, another 24-pounder halfway up the rock, and two 18-pounders in the battery at the top. In addition to this the men had use of a number of boats, with one armed with a 24-pounder carronade, which were used to intercept enemy ships.

Marshall's Naval Biography, when describing the process of hauling the guns to the summit, recorded that

French reactions

Despite the vulnerability of both Centaur and the Rock to a French gunboat attack while the process of fortification was being carried out, the French neglected to act. The governor of Martinique, Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse ordered work to begin on building a road to the coast opposite the rock, and the establishment of a battery there, but the British were forewarned by the black population of the island who were largely sympathetic to the British. A party was sent onshore, which succeeded in capturing the engineer sent to construct the battery, and three of his men. Work on the battery was abandoned after further British raids on the area.

HM Fort Diamond

By early February the guns had been installed and tested. The 18-pounders were able to completely command the passage between the rock and the island, forcing ships to avoid the channel. The winds and currents meant that these ships were then unable to enter the bay. With work complete by 7 February Hood decided to formalise the administration of the island, and wrote to the Admiralty, announcing that he had commissioned the rock as a sloop, under the name Fort Diamond. Lieutenant Maurice, who had impressed Hood with his efforts while establishing the position, was rewarded by being made commander. Diamond Rock was to be considered a captured enemy ship, and was technically treated as a tender to one of the boats stationed there, commissioned by the Admiralty as the sloop Diamond Rock, superseding Hood's use of Fort Diamond. This was a mere technicality, and when the boat fell into French hands, another replaced it, and in time the rock became known as the 'Sloop Diamond Rock'. The batteries were also named, the two 18-pounders at the summit were known as 'Fort Diamond' or 'Diamond Battery', while the 24-pounder halfway up was known as 'Hood's Battery'.

Life on the Rock

Picturesque Views of the Diamond Rock... A Lodgement under the Rock on the South-west Side

Maurice had a party of around 100 men under his command on the rock, with the usual officers found on a British warship, including a surgeon, purser, and a junior lieutenant to command the small supply vessel. A hospital was established, and food, gunpowder and ammunition were brought to the rock in boats, at first from Centaur, and then from Martinique, where it was purchased from sympathetic inhabitants. Water also had to be brought from the island, and large cisterns were built to store it. The men on the rock ran the risk of falling from the heights or being bitten by the fer-de-lance, a venomous snake inhabiting the rock.

First French assault

With the British presence on Diamond Rock firmly established, Hood departed with Centaur, and the French saw an opportunity to attack. Four boatloads of soldiers were despatched at night, though the sailors who rowed there were extremely pessimistic as to their chances. Exhausted by the time they arrived at the rock, the men were not able to resist the pull of the strong current and were swept out to sea. They were eventually able to make it back to Martinique, with the British only learning of the attempt several days later. The British could have easily sunk the French boats had the French made a daylight assault. Disheartened by their failure, the French made no further attempts to attack the fort from the island. Maurice and his men devoted their time after this to raiding, cutting out ships from the Martinique coast, and interdicting trade.

Villeneuve arrives

Diamond Rock in 2007

Main article: Trafalgar Campaign

On 14 May 1805, seventeen months after the British occupied the island, a large French fleet arrived in Fort-de-France Bay, having briefly exchanged fire with the British on Diamond Rock as they did so. The fleet, under Pierre de Villeneuve, was joined over the next few days by Spanish ships under Federico Gravina. As the Spanish ship San Rafael approached on 16 May, the British hoisted the French flag, luring the Spanish ship to pass close by. As she did so the British forces replaced the French colours with the British, and opened fire, taking the Spanish by surprise (such a false flag was considered a perfectly legitimate, indeed traditional, ruse de guerre during that era). Shortly after this it was discovered that the main cistern, holding a month's supply of water, had cracked in some earth tremors, and the leak had been made worse by the vibration from the guns. There was barely two weeks left, but fresh supplies were now unobtainable as a blockade of the rock began by a number of schooners, brigs and frigates.

The combined fleet carried a large number of soldiers, intended by Napoleon to be used to attack British possessions in the Caribbean. Villeneuve felt however that his orders were not clear, and remained at Fort-de-France, hoping to be joined by a fleet under Honoré Ganteaume, which unbeknownst to him had been unable to break the blockade of Brest. For two weeks Villeneuve lingered in the bay, until finally being persuaded by Villaret de Joyeuse to use his forces to capture Diamond Rock, a thorn in his side for the past seventeen months. Villeneuve gave Captain Julien Cosmao of the 74-gun Pluton command of the expedition. He was to take his ship, the 74-gun Berwick, the 36-gun Sirène, a corvette, schooner, eleven gunboats, and between three and four hundred soldiers (in addition to the ships' crews), and retake the rock.

Battle

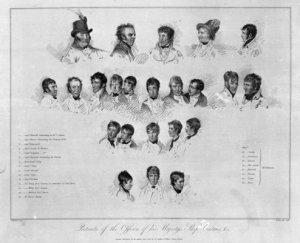

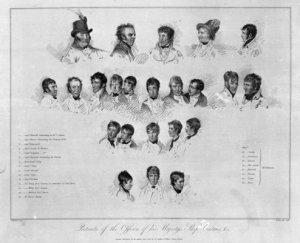

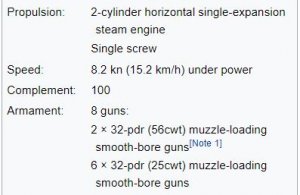

A collection of portraits of those involved in the establishment, operation and defence of Diamond Rock. Centre, top row, is Captain Murray Maxwell, commanding officer of HMS Centaur. Second from left, top row, is James Maurice, commander of the rock. His name is spelt here 'Morris'.

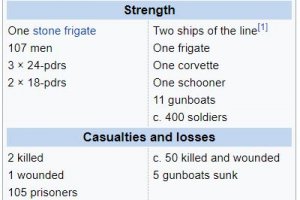

The flotilla left their anchorage on 29 May, but were not able to work into a position to attack windward of the rock until 31 May. Lieutenant Maurice assessed the overwhelming strength of the French, and having decided that it would be impossible to hold the lower stages, spiked the guns covering the landing stage, scuttled the launch, and withdrew his forces to defend the upper levels. Four Spanish gunboats from the ships San Rafael, Argonauta, España and Firme participated in the attack, with a Spanish gunboat being the first to disembark troops on the rock under fire from the British positions. Cosmao began an intense bombardment while the infantry forced their way onto the landing stage, losing three gunboats and two rowing boats full of soldiers as they did so. The attacking force had however neglected to bring any scaling ladders, and could not assault the sheer rock sides. Instead they were forced to besiege the British forces in the upper levels. By 2 June, with his ammunition almost exhausted and water supplies running critically short, Maurice opened negotiations.

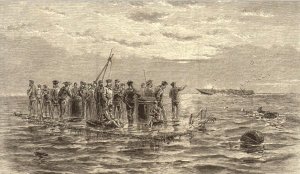

At four o'clock that afternoon flag of truce was displayed and a senior French officer was despatched in a schooner to offer terms. By 5 Maurice had agreed to surrender Diamond Rock, the officers were to retain their swords and the men would remain under their orders. They were to be taken to Fort-de-France, and from there repatriated to a British settlement at the first opportunity, under parole. With these terms agreed, the British surrendered Diamond Rock. The British had two men killed and one man wounded in the battle. French casualties were harder to judge, Maurice estimated they amounted to seventy, the French commander of the landing force made a 'hasty calculation' of fifty. In addition to this the British had sunk five large boats, and potentially inflicted further casualties during the bombardment of the French warships. Maurice and his men were taken off the rock on the morning of 6 June and put on board the Pluton and Berwick.

Aftermath

Maurice was returned to Barbados by 6 June, and sent a letter dated that day to Horatio Nelson, who had recently arrived in the Caribbean in search of Villeneuve's fleet.

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!csearch;searchTerm=Diamond_Rock;start=0

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!csearch;searchTerm=Diamond_Rock;start=0

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

31 May 1805 - Bombardment of "HMS Diamond Rock" commenced.

The Battle of Diamond Rock took place between 31 May and 2 June 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars.

The Battle of Diamond Rock took place between 31 May and 2 June 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars. It was an attempt by Franco-Spanish force despatched under Captain Julien Cosmao to retake Diamond Rock, at the entrance to the bay leading to Fort-de-France, from the British forces that had occupied it over a year before.

The French in Martinique had been unable to oust the defenders from the strategically important rock, and the British garrison was able to control access to Fort-de-France Bay, firing on ships attempting to enter it with guns they had placed on the cliffs. The arrival of a large combined Franco-Spanish fleet in May changed the strategic situation. The French commander, Pierre de Villeneuve, had vague orders to attack British possessions in the Caribbean, but instead waited at Martinique for clearer instructions. He was finally persuaded to authorise an assault on the British position, and a Franco-Spanish flotilla was despatched to storm the rock. Already short of water, the defenders held on in the summit for several days, while the French, who had neglected to bring scaling ladders, could make little headway.

The British, short of both water and ammunition, eventually negotiated the surrender of the rock after several days under fire. As Diamond Rock was legally considered a Royal Navy vessel, and the commander was legally "captain" of it, after repatriation, he was tried by court-martial (as the law dictated in any case where a captain loses his ship, regardless of the cause), but was honourably acquitted.

The Franco-Spanish combined fleet under Captain Cosmao attacking Diamond Rock, by Auguste Mayer

Background

Diamond Rock is fortified

Diamond Rock had been fortified in January 1804 on the orders of Commodore Samuel Hood. Hood had been active in the West Indies, protecting British convoys from French privateers issuing out of the two major naval bases the French retained in the Caribbean, at Guadeloupe and Martinique. The privateers had captured a number of valuable cargoes and were diverting British warships to protect the merchant fleets. Hood decided to blockade Martinique, and thus curtail the privateers and intercept supplies destined for the French garrison. Patrolling off the bay at the southern end of the island, in which one of Martinique's two main ports, Fort-de-France, was located, Hood saw that if Diamond Rock could be occupied, it would allow the British to effectively control the shipping approaching the ports on the western side, as the currents around the island made the easiest approaches mean passing within sight of Diamond Rock.

A cannon is hauled up to the summit of the rock suspended by a cable lashed to the base of Centaur's mainmast

Hood reconnoitered Diamond Rock and considered it excellently defensible, with the only possible landing site being on the western side. He wrote that 'thirty riflemen will keep the hill against ten thousand ... it is a perfect naval post.' A party of men were landed on 7 January 1804, from Hood's flagship HMS Centaur, under the command of Centaur's first lieutenant James Wilkes Maurice. They promptly fortified the small cove they had landed at with their launch's 24-pounder, and established forges and artificers' workshops in a cave at the base of the rock. After fixing ladders and ropes to scale the sheer sides of the rock, they were able to access the summit and began to establish messes and sleeping areas in a number of small caves. Bats were driven out by burning bales of hay, and a space was cleared by blasting at the top of the rock in order to establish a battery. In February a number of guns were transferred over from Centaur, with two 24-pounders being installed in a cave near sea level, another 24-pounder halfway up the rock, and two 18-pounders in the battery at the top. In addition to this the men had use of a number of boats, with one armed with a 24-pounder carronade, which were used to intercept enemy ships.

Marshall's Naval Biography, when describing the process of hauling the guns to the summit, recorded that

| “ | Lieutenant Maurice having succeeded in scrambling up the side of the rock ..., and fastened one end of an 8-inch hawser to a pinnacle, the viol-block was converted into a traveller, with a purchase-block lashed thereto, and the other end of the hawser set up, as a jack-stay, round the Centaur's main-mast. The gun being slung to the viol, the purchase-fall was brought to the capstern. In this manner the desired object was effected in the course of a week, during which time Lieutenant Maurice and the working party on shore suffered most dreadfully from excessive heat and fatigue, being constantly exposed to the sun, and frequently obliged to lower themselves down over immense precipices to attend the ascent of the guns, and bear them off from the innumerable projections against which they swung whenever the ship took a shear... | ” |

French reactions

Despite the vulnerability of both Centaur and the Rock to a French gunboat attack while the process of fortification was being carried out, the French neglected to act. The governor of Martinique, Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse ordered work to begin on building a road to the coast opposite the rock, and the establishment of a battery there, but the British were forewarned by the black population of the island who were largely sympathetic to the British. A party was sent onshore, which succeeded in capturing the engineer sent to construct the battery, and three of his men. Work on the battery was abandoned after further British raids on the area.

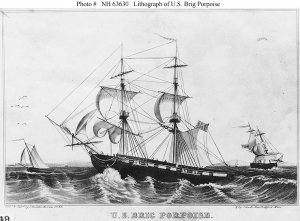

HM Fort Diamond

By early February the guns had been installed and tested. The 18-pounders were able to completely command the passage between the rock and the island, forcing ships to avoid the channel. The winds and currents meant that these ships were then unable to enter the bay. With work complete by 7 February Hood decided to formalise the administration of the island, and wrote to the Admiralty, announcing that he had commissioned the rock as a sloop, under the name Fort Diamond. Lieutenant Maurice, who had impressed Hood with his efforts while establishing the position, was rewarded by being made commander. Diamond Rock was to be considered a captured enemy ship, and was technically treated as a tender to one of the boats stationed there, commissioned by the Admiralty as the sloop Diamond Rock, superseding Hood's use of Fort Diamond. This was a mere technicality, and when the boat fell into French hands, another replaced it, and in time the rock became known as the 'Sloop Diamond Rock'. The batteries were also named, the two 18-pounders at the summit were known as 'Fort Diamond' or 'Diamond Battery', while the 24-pounder halfway up was known as 'Hood's Battery'.

Life on the Rock

Picturesque Views of the Diamond Rock... A Lodgement under the Rock on the South-west Side

Maurice had a party of around 100 men under his command on the rock, with the usual officers found on a British warship, including a surgeon, purser, and a junior lieutenant to command the small supply vessel. A hospital was established, and food, gunpowder and ammunition were brought to the rock in boats, at first from Centaur, and then from Martinique, where it was purchased from sympathetic inhabitants. Water also had to be brought from the island, and large cisterns were built to store it. The men on the rock ran the risk of falling from the heights or being bitten by the fer-de-lance, a venomous snake inhabiting the rock.

First French assault

With the British presence on Diamond Rock firmly established, Hood departed with Centaur, and the French saw an opportunity to attack. Four boatloads of soldiers were despatched at night, though the sailors who rowed there were extremely pessimistic as to their chances. Exhausted by the time they arrived at the rock, the men were not able to resist the pull of the strong current and were swept out to sea. They were eventually able to make it back to Martinique, with the British only learning of the attempt several days later. The British could have easily sunk the French boats had the French made a daylight assault. Disheartened by their failure, the French made no further attempts to attack the fort from the island. Maurice and his men devoted their time after this to raiding, cutting out ships from the Martinique coast, and interdicting trade.

Villeneuve arrives

Diamond Rock in 2007

Main article: Trafalgar Campaign

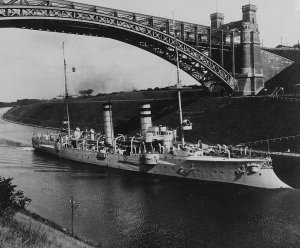

On 14 May 1805, seventeen months after the British occupied the island, a large French fleet arrived in Fort-de-France Bay, having briefly exchanged fire with the British on Diamond Rock as they did so. The fleet, under Pierre de Villeneuve, was joined over the next few days by Spanish ships under Federico Gravina. As the Spanish ship San Rafael approached on 16 May, the British hoisted the French flag, luring the Spanish ship to pass close by. As she did so the British forces replaced the French colours with the British, and opened fire, taking the Spanish by surprise (such a false flag was considered a perfectly legitimate, indeed traditional, ruse de guerre during that era). Shortly after this it was discovered that the main cistern, holding a month's supply of water, had cracked in some earth tremors, and the leak had been made worse by the vibration from the guns. There was barely two weeks left, but fresh supplies were now unobtainable as a blockade of the rock began by a number of schooners, brigs and frigates.

The combined fleet carried a large number of soldiers, intended by Napoleon to be used to attack British possessions in the Caribbean. Villeneuve felt however that his orders were not clear, and remained at Fort-de-France, hoping to be joined by a fleet under Honoré Ganteaume, which unbeknownst to him had been unable to break the blockade of Brest. For two weeks Villeneuve lingered in the bay, until finally being persuaded by Villaret de Joyeuse to use his forces to capture Diamond Rock, a thorn in his side for the past seventeen months. Villeneuve gave Captain Julien Cosmao of the 74-gun Pluton command of the expedition. He was to take his ship, the 74-gun Berwick, the 36-gun Sirène, a corvette, schooner, eleven gunboats, and between three and four hundred soldiers (in addition to the ships' crews), and retake the rock.

Battle

A collection of portraits of those involved in the establishment, operation and defence of Diamond Rock. Centre, top row, is Captain Murray Maxwell, commanding officer of HMS Centaur. Second from left, top row, is James Maurice, commander of the rock. His name is spelt here 'Morris'.

The flotilla left their anchorage on 29 May, but were not able to work into a position to attack windward of the rock until 31 May. Lieutenant Maurice assessed the overwhelming strength of the French, and having decided that it would be impossible to hold the lower stages, spiked the guns covering the landing stage, scuttled the launch, and withdrew his forces to defend the upper levels. Four Spanish gunboats from the ships San Rafael, Argonauta, España and Firme participated in the attack, with a Spanish gunboat being the first to disembark troops on the rock under fire from the British positions. Cosmao began an intense bombardment while the infantry forced their way onto the landing stage, losing three gunboats and two rowing boats full of soldiers as they did so. The attacking force had however neglected to bring any scaling ladders, and could not assault the sheer rock sides. Instead they were forced to besiege the British forces in the upper levels. By 2 June, with his ammunition almost exhausted and water supplies running critically short, Maurice opened negotiations.

At four o'clock that afternoon flag of truce was displayed and a senior French officer was despatched in a schooner to offer terms. By 5 Maurice had agreed to surrender Diamond Rock, the officers were to retain their swords and the men would remain under their orders. They were to be taken to Fort-de-France, and from there repatriated to a British settlement at the first opportunity, under parole. With these terms agreed, the British surrendered Diamond Rock. The British had two men killed and one man wounded in the battle. French casualties were harder to judge, Maurice estimated they amounted to seventy, the French commander of the landing force made a 'hasty calculation' of fifty. In addition to this the British had sunk five large boats, and potentially inflicted further casualties during the bombardment of the French warships. Maurice and his men were taken off the rock on the morning of 6 June and put on board the Pluton and Berwick.

Aftermath

Maurice was returned to Barbados by 6 June, and sent a letter dated that day to Horatio Nelson, who had recently arrived in the Caribbean in search of Villeneuve's fleet.

Naval procedure at the time was that all commanders who lost their ships automatically faced a court martial. Accordingly, Maurice was tried by a court martial convened aboard the 28-gun HMS Circe in Carlisle Bay on 24 June. Maurice was honourably acquitted for the loss, the verdict notingMy Lord

IT is with the greatest sorrow I have to inform you of the loss of the Diamond Rock, under my command, which was obliged to surrender on the 2d ist., after three days' attack from a squadron of two sail of the line, one frigate, one brig, a schooner, eleven gun-boats and, from the nearest calculation, 1500 troops. The want of ammunition and water was the sole occasion of its unfortunate loss.... [our losses were] only two killed and one wounded. The enemy, from the nearest account I have been able to obtain, lost on shore 30 killed and 40 wounded: they also lost three gun-boats and two rowing boats.

Villeneuve had retaken the rock, but the day the attack began the frigate Didon had arrived with orders from Napoleon. Villeneuve was ordered to take his force and attack British possessions, before returning in force to Europe, hopefully having in the meantime been joined by Ganteaume's fleet. But by now his supplies were so low that he could attempt little more than harassing some of the smaller British islands. Anti-French feelings grew in the Spanish commander Don Federico Gravina after the capture of the Diamond Rock. Gravina wanted to invade the island of Trinidad, under British rule since its capture from the Spanish a couple of years before. Villeneuve left Fort-de-France on 5 June, and on 7 June two French frigates sighted a convoy of 16 British merchants, and Villeneuve signalled general chase. The Spanish 80-gun ship of the line Argonauta and the two frigates chased down and captured 15 of the 16 merchants. The convoy was laden with sugar, rum, coffee, cotton and other products. From them he learnt that Nelson had arrived in the West Indies, in hot pursuit of Villeneuve. Shocked, Villeneuve abandoned his plans to raid the British colonies and immediately began preparations for the return voyage. The fleet got under-way on 11 June, causing one of the army officers attached to the fleet, General Honoré Charles Reille, to note:the Court is of the opinion that Captain J. W. Maurice, the Officers and Company of His Majesty's late sloop Diamond Rock did every thing in their power to the very last, in the defence of the Rock, and against a most superior force ... [Maurice] did not surrender the Diamond until he was unable to make further defence for want of water and ammunition, the Court do therefore honourably acquit Captain Maurice accordingly.

The capture of Diamond Rock and the seizing of 15 merchant ships were the only successes that the combined fleet had during their Caribbean campaign. The rock remained in French hands until the capture of Martinique in 1809.We have been masters of the sea for three weeks with a landing force of 7000 to 8000 men and have not been able to attack a single island.

Battle of Diamond Rock - Wikipedia

Stone frigate - Wikipedia

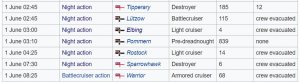

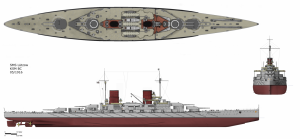

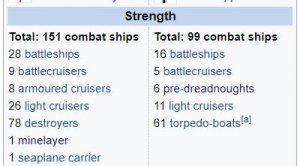

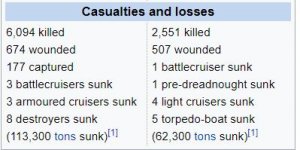

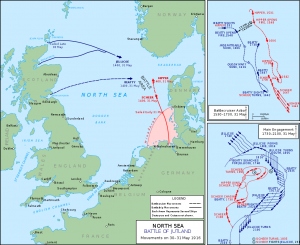

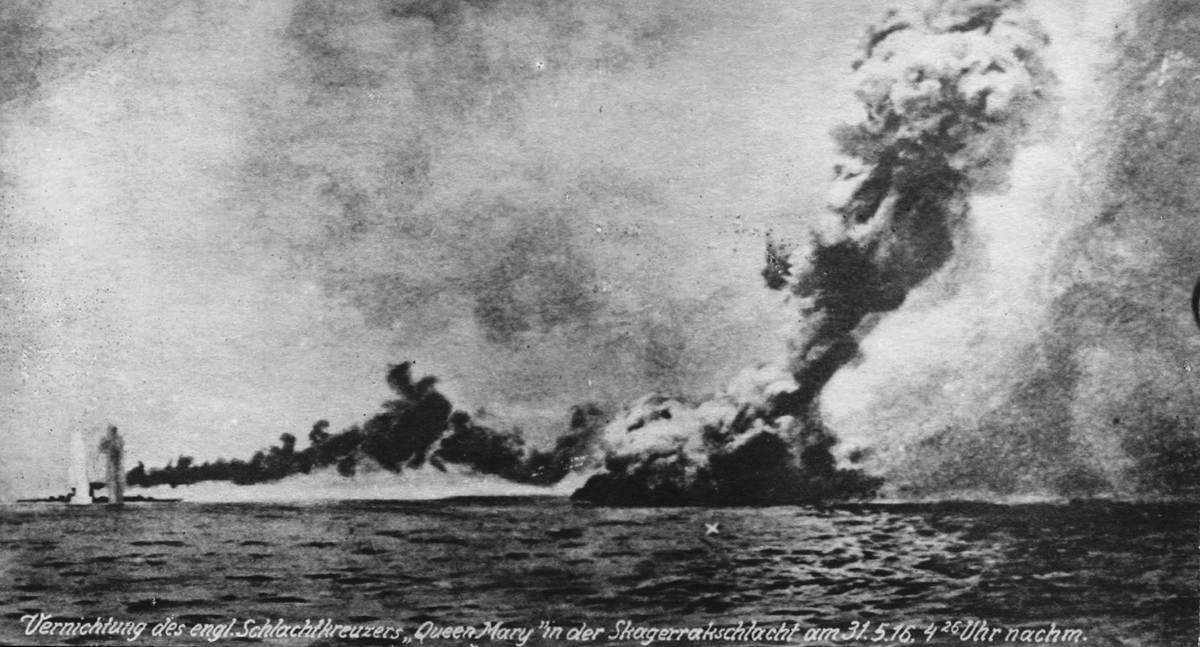

that Lützow, Elbing and Rostock had been scuttled was withheld, on the grounds this information would not be known to the enemy. The victory of the Skagerrak was celebrated in the press, children were given a holiday and the nation celebrated. The Kaiser announced a new chapter in world history. Post-war, the official German history hailed the battle as a victory and it continued to be celebrated until after World War II.

that Lützow, Elbing and Rostock had been scuttled was withheld, on the grounds this information would not be known to the enemy. The victory of the Skagerrak was celebrated in the press, children were given a holiday and the nation celebrated. The Kaiser announced a new chapter in world history. Post-war, the official German history hailed the battle as a victory and it continued to be celebrated until after World War II.