Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

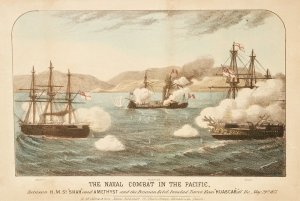

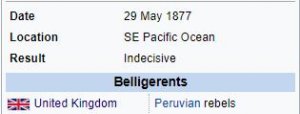

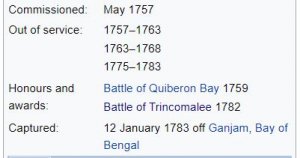

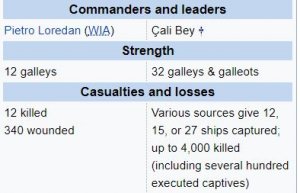

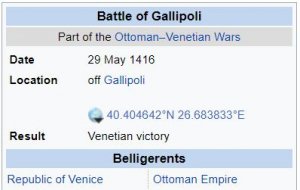

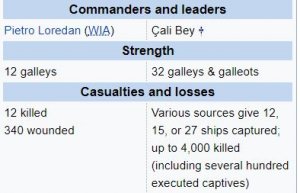

29 May 1416 - Battle of Gallipoli - Venetians defeat Ottoman Turks

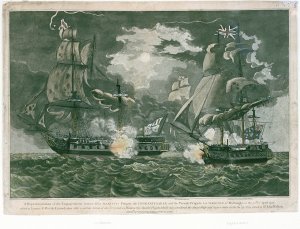

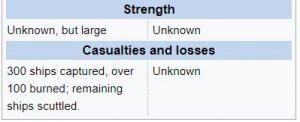

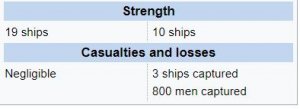

The Battle of Gallipoli occurred on 29 May 1416 between a squadron of the Venetian navy and the fleet of the Ottoman Empire off the Ottoman naval base of Gallipoli. The battle was the main episode of a brief conflict between the two powers, resulting from Ottoman attacks against Venetian possessions and shipping in the Aegean Sea in late 1415. The Venetian fleet, under Pietro Loredan, was charged with transporting Venetian envoys to the Sultan, but was authorized to attack if the Ottomans refused to negotiate. The subsequent events are known chiefly from a letter written by Loredan after the battle. The Ottomans exchanged fire with the Venetian ships as soon as the Venetian fleet approached Gallipoli, forcing the Venetians to withdraw.

On the next day, the two fleets manoeuvred and fought off Gallipoli, but during the evening, Loredan managed to contact the Ottoman authorities and inform them of his diplomatic mission. Despite assurances that the Ottomans would welcome the envoys, when the Venetian fleet approached the city on the next day, the Ottoman fleet sailed to meet the Venetians and the two sides quickly became embroiled in battle. The Venetians scored a crushing victory, killing the Ottoman admiral, capturing a large part of the Ottoman fleet, and taking large numbers prisoner, of whom many—particularly the Christians serving voluntarily in the Ottoman fleet—were executed. The Venetians then retired to Tenedos to replenish their supplies and rest. Although a crushing Venetian victory, which confirmed Venetian naval superiority in the Aegean Sea for the next few decades, the settlement of the conflict was delayed until a peace treaty was signed in 1419.

Background

Map of the southern Balkans and western Anatolia in 1410, during the later phase of the Ottoman Interregnum

In 1413, the Ottoman prince Mehmed I ended the civil war of the Ottoman Interregnum and established himself as Sultan and the sole master of the Ottoman realm. The Republic of Venice, as the premier maritime and commercial power in the area, endeavoured to renew the treaties it had concluded with Mehmed's predecessors during the civil war, and in May 1414, its bailo in the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, Francesco Foscarini, was instructed to proceed to the Sultan's court to that effect. Foscarini failed, however, as Mehmed campaigned in Anatolia, and Venetian envoys were traditionally instructed not to move too far from the shore (and the Republic's reach); Foscarini had yet to meet the Sultan by July 1415, when Mehmed's displeasure at this delay was conveyed to the Venetian authorities. In the meantime, tensions between the two powers mounted, as the Ottomans moved to re-establish a sizeable navy and launched several raids that challenged Venetian naval hegemony in the Aegean Sea.

During his 1414 campaign in Anatolia, Mehmed came to Smyrna, where several of the most important Latin rulers of the Aegean—the Genoese lords of Chios, Phokaia, and Lesbos, and even the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller—came to do him obeisance. According to the contemporary Byzantine historian Doukas (c. 1400 – after 1462), the absence of the Duke of Naxos from this assembly provoked the ire of the Sultan, who in retaliation equipped a fleet of 30 vessels, under the command of Çali Bey, and in late 1415 sent it to raid the Duke's domains in the Cyclades. The Ottoman fleet ravaged the islands, and carried off a large part of the inhabitants of Andros, Paros, and Melos.

In June 1414, Ottoman ships raided the Venetian colony of Euboea and pillaged its capital, Negroponte, taking almost all its inhabitants prisoner; out of some 2,000 captives, the Republic was able after years secure the release of 200 mostly elderly, women, and children, the rest being sold as slaves. Furthermore, in the autumn of 1415, an Ottoman fleet of 42 ships—six galleys, 16 galleots, and the rest smaller brigantines—tried to intercept Venetian merchant convoy coming from the Black Sea at the island of Tenedos, at the southern entrance of the Dardanelles. The Venetian vessels were delayed at Constantinople by bad weather, but managed to pass through the Ottoman fleet and outrun its pursuit to the safety of Negroponte. The Ottoman fleet instead raided Euboea, including an attack on the fortress of Oreos (Loreo) in northern Euboea, but its defenders under the castellan Taddeo Zane resisted with success. Nevertheless the Turks were able to once again ravage the rest of the island, carrying off 1,500 captives, so that the local inhabitants even petitioned the Signoria of Venice for permission to become tributaries of the Turks to guarantee their future safety—a demand categorically rejected by the Signoria on 4 February 1416.

In response to the Ottoman raids, the Great Council of Venice appointed Pietro Loredan as commander-in-chief and charged him with equipping a fleet of fifteen galleys; five were equipped in Venice, four at Candia, and one each at Negroponte, Napoli di Romania (Nauplia), Andros, and Corfu.a[›] Loredan's brother Giorgio, Jacopo Barbarigo, Cristoforo Dandolo, and Pietro Contarini were appointed as galley captains (sopracomiti), while Andrea Foscolo and Delfino Venier were designated as provveditori of the fleet and envoys to the Sultan. While Foscolo was charged with a mission to the Principality of Achaea, Venier was tasked with reaching a new agreement with the Sultan on the basis of the treaty concluded between Musa Çelebi and the Venetian envoy Giacomo Trevisan in 1411, and with securing the release of the Venetian prisoners taken in 1414. Loredan's appointment was unusual, as he had served recently as Captain of the Gulf, and law forbade anyone who had held the position from holding the same for three years after; however, the Great Council overrode this rule due to the de facto state of war with the Ottomans. In a further move calculated to bolster Loredan's authority (and appeal to his vanity), an old rule that had fallen into disuse was revived, whereby only the captain-general had the right to carry the Banner of Saint Mark on his flagship, rather than every sopracomito. In a rare display of determination on behalf of the Venetian government, the Council voted almost unanimously to authorize Loredan to attack if the Ottomans were unwilling to negotiate a cessation of hostilities.

Map of the Dardanelles Straits and their vicinity. Gallipoli (Gelibolu) is marked on the northern entrance of the Straits.

The main target of Loredan's fleet was to be Gallipoli. The city was the "key of the Dardanelles" and one of the most important strategic positions in the Eastern Mediterranean. At the time it was also the main Turkish naval base and provided a safe haven for their corsairs raiding Venetian colonies in the Aegean. With Constantinople still in Christian hands, Gallipoli had also for decades been the main crossing point for the Ottoman armies from Anatolia to Europe. As a result of its trategic importance, Sultan Bayezid I took care to improve its fortifications, rebuilding the citadel and strengthening the harbour defences. The harbour had a seaward wall and a narrow entrance leading to an outer basin, separated from an inner basin by a bridge, where Bayezid erected a three-storey tower. When Ruy González de Clavijo visited the city in 1403, he reported seeing its citadel full of troops, a large arsenal, and 40 ships in the harbour.

Bayezid aimed to use his warships in Gallipoli to control (and tax) the passage of shipping through the Dardanelles, an ambition which brought him into direct conflict with Venetian interests in the area. While the Ottoman fleet was not yet strong enough to face the Venetians, it forced the latter to provide armed escort to their trade convoys passing through the Dardanelles. Securing right of unimpeded passage through the Dardanelles was a chief issue in Venice's diplomatic relations with the Ottomans: the Republic had secured this in the 1411 treaty with Musa Çelebi, but the failure to renew that agreement in 1414 had again rendered Gallipoli "the main object of dispute in Venetian-Ottoman relations", and the Ottoman naval activity in 1415, based in Gallipoli, further underscored its importance.

Battle

The events before and during the battle are described in detail in a letter sent by Loredan to the Signoria on 2 June 1416, which was included by Sanudo in his (posthumously published) History of the Doges of Venice, while Doukas provides a brief and somewhat different account. According to Loredan's letter, his fleet was delayed by contrary winds and reached Tenedos on 24 May, and did not enter the Dardanelles until the 27th, when they arrived near Gallipoli. Loredan reports that the Venetians took care to avoid projecting any hostile intentions, but the Ottomans, who had assembled a large force of infantry and 200 cavalry on the shore, began firing on them with arrows. Loredan dispersed his ships to avoid casualties, but the tide was drawing them closer to the shore. Loredan tried to signal the Ottomans that they had no hostile intentions, but the latter kept firing poisoned arrows at them, until Loredan ordered a few cannon shots that killed a few soldiers and forced the rest to retire from the shore.

At dawn on the next day, Loredan sent two galleys, bearing the Banner of Saint Mark, to the entry of the port of Gallipoli to open negotiations. In response the Turks sent 32 ships to attack them. Loredan withdrew his two galleys, and began to withdraw, while shooting at the Turkish ships, in order to lure them away from Gallipoli. As the Ottoman ships could not keep up with their oars, they set sail as well; on the Venetian side, the galley from Napoli di Romania tarried during the manoeuvre and was in danger of being caught by the pursuing Ottoman ships, so that Loredan likewise ordered his ships to set sail. Once they were had made ready for combat, Loredan ordered his ten galleys to lower sails, turn about, and face the Ottoman fleet. At that point, however, the eastern wind rose suddenly, and the Ottomans decided to break off the pursuit and head back to Gallipoli. Loredan in turn tried to catch up with the Ottomans, firing at them with his guns and crossbows and launching grappling hooks at the Turkish ships, but the wind and the current allowed the Ottomans to retreat speedily behind the fortifications of Gallipoli. According to Loredan, the engagement lasted until the 22nd hour.

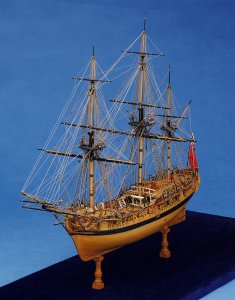

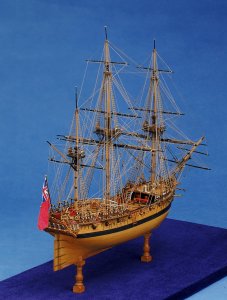

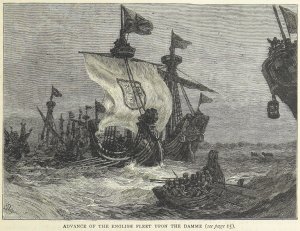

14th-century painting of a light galley, from an icon now at the Byzantine and Christian Museum at Athens

Loredan then sent a messenger to the Ottoman fleet commander to complain about the attack, insisting that his intentions were pacific, and that his sole purpose was to convey the two ambassadors to the Sultan. The Ottoman commander replied that he was ignorant of that fact, and that the fleet was meant to sail to the Danube and stop Mehmed's brother and rival for the throne, Mustafa Çelebi, from crossing from Wallachia into Ottoman Rumelia. The Ottoman commander informed Loredan that he and his crews could land and provision themselves without fear, and that the members of the embassy would be conveyed with the appropriate honours and safety to their destination. Loredan sent a notary, Thomas, with an interpreter to the Ottoman commander and the captain of the garrison of Gallipoli to express his regrets, but also to gauge the number, equipment, and dispositions of the Ottoman galleys. The Ottoman dignitaries reassured Thomas of their good will, and proposed to provide an armed escort for the ambassadors to bring them to the court of Sultan Mehmed.

After the envoy returned, the Venetian fleet, sailing with difficulty against the eastern wind, departed and sailed to a nearby bay to spend the night. On the next day, in accordance to the messages exchanged, Loredan led his ships towards Gallipoli to replenish his supplies of water, while leaving three galleys—those of his brother, of Dandolo, and of Capello of Candia—as a reserve. As soon as the Venetians approached the town, the Ottoman fleet sailed out of the harbour, and one of their galleys approached and fired a few cannon shots at the Venetian vessels. According to the account by Doukas, the Venetians were pursuing a merchant vessel of Lesbos thought to be Turkish origin, coming from Constantinople. The Ottomans likewise thought the merchant vessel was one of their own, and one of their galleys moved to defend the vessel.

The galley from Napoli, which sailed to his left, was again showing signs of disorder, so he ordered it moved to the right, away from the approaching Turks. Loredan had his ships withdraw a while, in order to draw the Turks further from Gallipoli and have the sun in the Venetians' back. Once ready, Loredan led his own flagship to attack the leading Ottoman galley. Its crew offered determined resistance, and the other Ottoman galleys came astern of Loredan's ship to his left, and launched volleys of arrows against him and his men. Loredan himself was wounded by an arrow below the eye and the nose, and by another that passed through his left hand, as well as other arrows that struck him with lesser effect. Nevertheless, the galley was captured after most of its crew was killed, and Loredan, after leaving a few men of his crew to guard it, turned against a galleot, which he captured as well. Again leaving a few of his men and his flag on it, he turned on the other Ottoman ships. The fight lasted from morning to the second hour of the night. The Venetians defeated the Ottoman fleet, killing its commander and many of the captains and crews, and capturing six great galleys and nine galleots, according to Loredan's account. Doukas claims that the Venetians captured 27 vessels in total, while the contemporary Egyptian chronicler Maqrizi reduced the number to twelve. Loredan gives a detailed breakdown of the ships captured by his men: his own ship captured a galley and a galleot of 20 banks of oars; the Contarini galley captured a galley; the galley of Giorgio Loredan captured two galleots of 22 banks and two galleots of 20 banks; the Grimani galley of Negroponte captured a galley; the galley of Jiacopo Barbarini captured a galleot of 23 banks and another of 19 banks; the same for the Capello galley; the galley of Girolamo Minotto from Napoli captured the Ottoman flagship galley, which had been defeated and pursued before by the Capello galley; the Venieri and Barbarigo galleys of Candia took a galley. Venetian casualties were light, twelve killed—mostly by drowning—and 340 wounded, most of them lightly. Maqrizi puts the total number of Ottoman dead at 4,000 men.

The Venetian fleet then approached Gallipoli and bombarded the port, without response from the Ottomans within the walls. The Venetians then retired about a mile from Gallipoli to recover their strength and tend to their wounded. Among the captive Ottoman crews were found to be many Christians—Genoese, Catalans, Cretans, Provencals, and Sicilians—who were all executed by hanging from the yardarms, while a certain Giorgio Calergi, who had participated in a revolt against Venice, was quartered at the deck of Loredan's flagship. Many of the Christian galley slaves also perished in combat, but about 1,100 were taken prisoner by the Venetians. Doukas places these events later, at Tenedos, where the Turkish prisoners were executed, while the Christian prisoners were divided into those who had been pressed into service as galley slaves, who were liberated, and those who had entered Ottoman service as mercenaries, who were impaled. After burning five galleots in sight of Gallipoli, Loredan made ready to retire with his ships to Tenedos to take on water, repair his ships, tend to his wounded and make new plans. The Venetian commander sent a new letter to the Ottoman commander in the city complaining of breach of faith and explaining that he would return from Tenedos to carry out his mission of escorting the ambassadors, but the Ottoman commander did not reply.

Aftermath

One of the Turkish captains that had been taken prisoner also composed a letter to the Sultan, stating that the Venetians had been attacked without cause. He also informed Loredan that the remnants of the Ottoman fleet were such that they posed no threat to him: a single galley and a few galleots and smaller vessels were seaworthy, while the rest of the galleys in Gallipoli were out of commission. At Tenedos, Loredan held a council of war, where the opinion was to return to Negroponte for provisions, for offloading the wounded, and for selling three of the galleys for prize money for the crews.b[›] Loredan disagreed, believing that they should keep up the pressure on the Turks, and resolved to return to Gallipoli to press for the passage of the ambassadors to the Sultan's court. He sent his brother with his ship to bring the more heavily wounded to Negroponte, and burned three of the captured galleys since they were too much of a burden—in his letter to the Signoria, he expressed the hope that his men would still be recompensed for them, his shipwrights estimating their value at 600 gold ducats.

The conflict was finally ended in November 1419, when a peace treaty was signed between the Sultan and the new Venetian bailo in Constantinople, Bertuccio Diedo, in which the Ottomans recognized by name Venice's overseas possessions, and agreed to an exchange of prisoners—those taken by the Ottomans from Euboea, and by Venice at Gallipoli.

The victory at Gallipoli ensured Venetian naval superiority for decades to come, but also led the Venetians to complacency and over-confidence, as, according to historian Seth Parry, the "seemingly effortless trouncing of the Ottoman fleet confirmed the Venetians in their beliefs that they were vastly superior to the Turks in naval warfare". During the long Siege of Thessalonica (1422–1430) and subsequent conflicts over the course of the century, however, "the Venetians would learn to their discomfiture that naval superiority alone could not guarantee an everlasting position of strength in the eastern Mediterranean".

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

29 May 1416 - Battle of Gallipoli - Venetians defeat Ottoman Turks

The Battle of Gallipoli occurred on 29 May 1416 between a squadron of the Venetian navy and the fleet of the Ottoman Empire off the Ottoman naval base of Gallipoli. The battle was the main episode of a brief conflict between the two powers, resulting from Ottoman attacks against Venetian possessions and shipping in the Aegean Sea in late 1415. The Venetian fleet, under Pietro Loredan, was charged with transporting Venetian envoys to the Sultan, but was authorized to attack if the Ottomans refused to negotiate. The subsequent events are known chiefly from a letter written by Loredan after the battle. The Ottomans exchanged fire with the Venetian ships as soon as the Venetian fleet approached Gallipoli, forcing the Venetians to withdraw.

On the next day, the two fleets manoeuvred and fought off Gallipoli, but during the evening, Loredan managed to contact the Ottoman authorities and inform them of his diplomatic mission. Despite assurances that the Ottomans would welcome the envoys, when the Venetian fleet approached the city on the next day, the Ottoman fleet sailed to meet the Venetians and the two sides quickly became embroiled in battle. The Venetians scored a crushing victory, killing the Ottoman admiral, capturing a large part of the Ottoman fleet, and taking large numbers prisoner, of whom many—particularly the Christians serving voluntarily in the Ottoman fleet—were executed. The Venetians then retired to Tenedos to replenish their supplies and rest. Although a crushing Venetian victory, which confirmed Venetian naval superiority in the Aegean Sea for the next few decades, the settlement of the conflict was delayed until a peace treaty was signed in 1419.

Background

Map of the southern Balkans and western Anatolia in 1410, during the later phase of the Ottoman Interregnum

In 1413, the Ottoman prince Mehmed I ended the civil war of the Ottoman Interregnum and established himself as Sultan and the sole master of the Ottoman realm. The Republic of Venice, as the premier maritime and commercial power in the area, endeavoured to renew the treaties it had concluded with Mehmed's predecessors during the civil war, and in May 1414, its bailo in the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, Francesco Foscarini, was instructed to proceed to the Sultan's court to that effect. Foscarini failed, however, as Mehmed campaigned in Anatolia, and Venetian envoys were traditionally instructed not to move too far from the shore (and the Republic's reach); Foscarini had yet to meet the Sultan by July 1415, when Mehmed's displeasure at this delay was conveyed to the Venetian authorities. In the meantime, tensions between the two powers mounted, as the Ottomans moved to re-establish a sizeable navy and launched several raids that challenged Venetian naval hegemony in the Aegean Sea.

During his 1414 campaign in Anatolia, Mehmed came to Smyrna, where several of the most important Latin rulers of the Aegean—the Genoese lords of Chios, Phokaia, and Lesbos, and even the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller—came to do him obeisance. According to the contemporary Byzantine historian Doukas (c. 1400 – after 1462), the absence of the Duke of Naxos from this assembly provoked the ire of the Sultan, who in retaliation equipped a fleet of 30 vessels, under the command of Çali Bey, and in late 1415 sent it to raid the Duke's domains in the Cyclades. The Ottoman fleet ravaged the islands, and carried off a large part of the inhabitants of Andros, Paros, and Melos.

In June 1414, Ottoman ships raided the Venetian colony of Euboea and pillaged its capital, Negroponte, taking almost all its inhabitants prisoner; out of some 2,000 captives, the Republic was able after years secure the release of 200 mostly elderly, women, and children, the rest being sold as slaves. Furthermore, in the autumn of 1415, an Ottoman fleet of 42 ships—six galleys, 16 galleots, and the rest smaller brigantines—tried to intercept Venetian merchant convoy coming from the Black Sea at the island of Tenedos, at the southern entrance of the Dardanelles. The Venetian vessels were delayed at Constantinople by bad weather, but managed to pass through the Ottoman fleet and outrun its pursuit to the safety of Negroponte. The Ottoman fleet instead raided Euboea, including an attack on the fortress of Oreos (Loreo) in northern Euboea, but its defenders under the castellan Taddeo Zane resisted with success. Nevertheless the Turks were able to once again ravage the rest of the island, carrying off 1,500 captives, so that the local inhabitants even petitioned the Signoria of Venice for permission to become tributaries of the Turks to guarantee their future safety—a demand categorically rejected by the Signoria on 4 February 1416.

In response to the Ottoman raids, the Great Council of Venice appointed Pietro Loredan as commander-in-chief and charged him with equipping a fleet of fifteen galleys; five were equipped in Venice, four at Candia, and one each at Negroponte, Napoli di Romania (Nauplia), Andros, and Corfu.a[›] Loredan's brother Giorgio, Jacopo Barbarigo, Cristoforo Dandolo, and Pietro Contarini were appointed as galley captains (sopracomiti), while Andrea Foscolo and Delfino Venier were designated as provveditori of the fleet and envoys to the Sultan. While Foscolo was charged with a mission to the Principality of Achaea, Venier was tasked with reaching a new agreement with the Sultan on the basis of the treaty concluded between Musa Çelebi and the Venetian envoy Giacomo Trevisan in 1411, and with securing the release of the Venetian prisoners taken in 1414. Loredan's appointment was unusual, as he had served recently as Captain of the Gulf, and law forbade anyone who had held the position from holding the same for three years after; however, the Great Council overrode this rule due to the de facto state of war with the Ottomans. In a further move calculated to bolster Loredan's authority (and appeal to his vanity), an old rule that had fallen into disuse was revived, whereby only the captain-general had the right to carry the Banner of Saint Mark on his flagship, rather than every sopracomito. In a rare display of determination on behalf of the Venetian government, the Council voted almost unanimously to authorize Loredan to attack if the Ottomans were unwilling to negotiate a cessation of hostilities.

Map of the Dardanelles Straits and their vicinity. Gallipoli (Gelibolu) is marked on the northern entrance of the Straits.

The main target of Loredan's fleet was to be Gallipoli. The city was the "key of the Dardanelles" and one of the most important strategic positions in the Eastern Mediterranean. At the time it was also the main Turkish naval base and provided a safe haven for their corsairs raiding Venetian colonies in the Aegean. With Constantinople still in Christian hands, Gallipoli had also for decades been the main crossing point for the Ottoman armies from Anatolia to Europe. As a result of its trategic importance, Sultan Bayezid I took care to improve its fortifications, rebuilding the citadel and strengthening the harbour defences. The harbour had a seaward wall and a narrow entrance leading to an outer basin, separated from an inner basin by a bridge, where Bayezid erected a three-storey tower. When Ruy González de Clavijo visited the city in 1403, he reported seeing its citadel full of troops, a large arsenal, and 40 ships in the harbour.

Bayezid aimed to use his warships in Gallipoli to control (and tax) the passage of shipping through the Dardanelles, an ambition which brought him into direct conflict with Venetian interests in the area. While the Ottoman fleet was not yet strong enough to face the Venetians, it forced the latter to provide armed escort to their trade convoys passing through the Dardanelles. Securing right of unimpeded passage through the Dardanelles was a chief issue in Venice's diplomatic relations with the Ottomans: the Republic had secured this in the 1411 treaty with Musa Çelebi, but the failure to renew that agreement in 1414 had again rendered Gallipoli "the main object of dispute in Venetian-Ottoman relations", and the Ottoman naval activity in 1415, based in Gallipoli, further underscored its importance.

Battle

The events before and during the battle are described in detail in a letter sent by Loredan to the Signoria on 2 June 1416, which was included by Sanudo in his (posthumously published) History of the Doges of Venice, while Doukas provides a brief and somewhat different account. According to Loredan's letter, his fleet was delayed by contrary winds and reached Tenedos on 24 May, and did not enter the Dardanelles until the 27th, when they arrived near Gallipoli. Loredan reports that the Venetians took care to avoid projecting any hostile intentions, but the Ottomans, who had assembled a large force of infantry and 200 cavalry on the shore, began firing on them with arrows. Loredan dispersed his ships to avoid casualties, but the tide was drawing them closer to the shore. Loredan tried to signal the Ottomans that they had no hostile intentions, but the latter kept firing poisoned arrows at them, until Loredan ordered a few cannon shots that killed a few soldiers and forced the rest to retire from the shore.

At dawn on the next day, Loredan sent two galleys, bearing the Banner of Saint Mark, to the entry of the port of Gallipoli to open negotiations. In response the Turks sent 32 ships to attack them. Loredan withdrew his two galleys, and began to withdraw, while shooting at the Turkish ships, in order to lure them away from Gallipoli. As the Ottoman ships could not keep up with their oars, they set sail as well; on the Venetian side, the galley from Napoli di Romania tarried during the manoeuvre and was in danger of being caught by the pursuing Ottoman ships, so that Loredan likewise ordered his ships to set sail. Once they were had made ready for combat, Loredan ordered his ten galleys to lower sails, turn about, and face the Ottoman fleet. At that point, however, the eastern wind rose suddenly, and the Ottomans decided to break off the pursuit and head back to Gallipoli. Loredan in turn tried to catch up with the Ottomans, firing at them with his guns and crossbows and launching grappling hooks at the Turkish ships, but the wind and the current allowed the Ottomans to retreat speedily behind the fortifications of Gallipoli. According to Loredan, the engagement lasted until the 22nd hour.

14th-century painting of a light galley, from an icon now at the Byzantine and Christian Museum at Athens

Loredan then sent a messenger to the Ottoman fleet commander to complain about the attack, insisting that his intentions were pacific, and that his sole purpose was to convey the two ambassadors to the Sultan. The Ottoman commander replied that he was ignorant of that fact, and that the fleet was meant to sail to the Danube and stop Mehmed's brother and rival for the throne, Mustafa Çelebi, from crossing from Wallachia into Ottoman Rumelia. The Ottoman commander informed Loredan that he and his crews could land and provision themselves without fear, and that the members of the embassy would be conveyed with the appropriate honours and safety to their destination. Loredan sent a notary, Thomas, with an interpreter to the Ottoman commander and the captain of the garrison of Gallipoli to express his regrets, but also to gauge the number, equipment, and dispositions of the Ottoman galleys. The Ottoman dignitaries reassured Thomas of their good will, and proposed to provide an armed escort for the ambassadors to bring them to the court of Sultan Mehmed.

After the envoy returned, the Venetian fleet, sailing with difficulty against the eastern wind, departed and sailed to a nearby bay to spend the night. On the next day, in accordance to the messages exchanged, Loredan led his ships towards Gallipoli to replenish his supplies of water, while leaving three galleys—those of his brother, of Dandolo, and of Capello of Candia—as a reserve. As soon as the Venetians approached the town, the Ottoman fleet sailed out of the harbour, and one of their galleys approached and fired a few cannon shots at the Venetian vessels. According to the account by Doukas, the Venetians were pursuing a merchant vessel of Lesbos thought to be Turkish origin, coming from Constantinople. The Ottomans likewise thought the merchant vessel was one of their own, and one of their galleys moved to defend the vessel.

The galley from Napoli, which sailed to his left, was again showing signs of disorder, so he ordered it moved to the right, away from the approaching Turks. Loredan had his ships withdraw a while, in order to draw the Turks further from Gallipoli and have the sun in the Venetians' back. Once ready, Loredan led his own flagship to attack the leading Ottoman galley. Its crew offered determined resistance, and the other Ottoman galleys came astern of Loredan's ship to his left, and launched volleys of arrows against him and his men. Loredan himself was wounded by an arrow below the eye and the nose, and by another that passed through his left hand, as well as other arrows that struck him with lesser effect. Nevertheless, the galley was captured after most of its crew was killed, and Loredan, after leaving a few men of his crew to guard it, turned against a galleot, which he captured as well. Again leaving a few of his men and his flag on it, he turned on the other Ottoman ships. The fight lasted from morning to the second hour of the night. The Venetians defeated the Ottoman fleet, killing its commander and many of the captains and crews, and capturing six great galleys and nine galleots, according to Loredan's account. Doukas claims that the Venetians captured 27 vessels in total, while the contemporary Egyptian chronicler Maqrizi reduced the number to twelve. Loredan gives a detailed breakdown of the ships captured by his men: his own ship captured a galley and a galleot of 20 banks of oars; the Contarini galley captured a galley; the galley of Giorgio Loredan captured two galleots of 22 banks and two galleots of 20 banks; the Grimani galley of Negroponte captured a galley; the galley of Jiacopo Barbarini captured a galleot of 23 banks and another of 19 banks; the same for the Capello galley; the galley of Girolamo Minotto from Napoli captured the Ottoman flagship galley, which had been defeated and pursued before by the Capello galley; the Venieri and Barbarigo galleys of Candia took a galley. Venetian casualties were light, twelve killed—mostly by drowning—and 340 wounded, most of them lightly. Maqrizi puts the total number of Ottoman dead at 4,000 men.

The Venetian fleet then approached Gallipoli and bombarded the port, without response from the Ottomans within the walls. The Venetians then retired about a mile from Gallipoli to recover their strength and tend to their wounded. Among the captive Ottoman crews were found to be many Christians—Genoese, Catalans, Cretans, Provencals, and Sicilians—who were all executed by hanging from the yardarms, while a certain Giorgio Calergi, who had participated in a revolt against Venice, was quartered at the deck of Loredan's flagship. Many of the Christian galley slaves also perished in combat, but about 1,100 were taken prisoner by the Venetians. Doukas places these events later, at Tenedos, where the Turkish prisoners were executed, while the Christian prisoners were divided into those who had been pressed into service as galley slaves, who were liberated, and those who had entered Ottoman service as mercenaries, who were impaled. After burning five galleots in sight of Gallipoli, Loredan made ready to retire with his ships to Tenedos to take on water, repair his ships, tend to his wounded and make new plans. The Venetian commander sent a new letter to the Ottoman commander in the city complaining of breach of faith and explaining that he would return from Tenedos to carry out his mission of escorting the ambassadors, but the Ottoman commander did not reply.

Aftermath

One of the Turkish captains that had been taken prisoner also composed a letter to the Sultan, stating that the Venetians had been attacked without cause. He also informed Loredan that the remnants of the Ottoman fleet were such that they posed no threat to him: a single galley and a few galleots and smaller vessels were seaworthy, while the rest of the galleys in Gallipoli were out of commission. At Tenedos, Loredan held a council of war, where the opinion was to return to Negroponte for provisions, for offloading the wounded, and for selling three of the galleys for prize money for the crews.b[›] Loredan disagreed, believing that they should keep up the pressure on the Turks, and resolved to return to Gallipoli to press for the passage of the ambassadors to the Sultan's court. He sent his brother with his ship to bring the more heavily wounded to Negroponte, and burned three of the captured galleys since they were too much of a burden—in his letter to the Signoria, he expressed the hope that his men would still be recompensed for them, his shipwrights estimating their value at 600 gold ducats.

The conflict was finally ended in November 1419, when a peace treaty was signed between the Sultan and the new Venetian bailo in Constantinople, Bertuccio Diedo, in which the Ottomans recognized by name Venice's overseas possessions, and agreed to an exchange of prisoners—those taken by the Ottomans from Euboea, and by Venice at Gallipoli.

The victory at Gallipoli ensured Venetian naval superiority for decades to come, but also led the Venetians to complacency and over-confidence, as, according to historian Seth Parry, the "seemingly effortless trouncing of the Ottoman fleet confirmed the Venetians in their beliefs that they were vastly superior to the Turks in naval warfare". During the long Siege of Thessalonica (1422–1430) and subsequent conflicts over the course of the century, however, "the Venetians would learn to their discomfiture that naval superiority alone could not guarantee an everlasting position of strength in the eastern Mediterranean".