Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

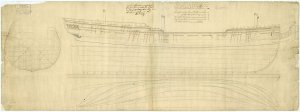

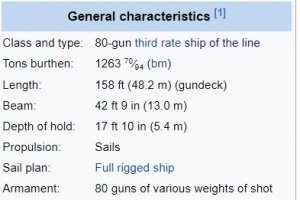

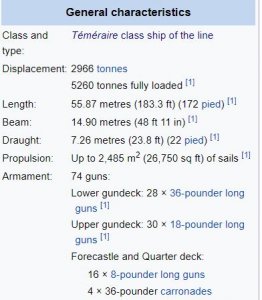

31 May 1791 – Launch of French Suffren, renamed Redoutable, a Téméraire class 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy.

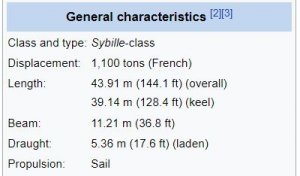

The

Redoutable was a

Téméraire class 74-gun ship of the line of the

French Navy. She took part in the battles of the French Revolutionary Wars in the Brest squadron, served in the Caribbean in 1803, and duelled with

HMS Victory during the

Battle of Trafalgar, killing

Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson during the action. She sank in the storm that followed the battle.

Built as

Suffren, the ship was commissioned in the Brest squadron of the French fleet. After her crew took part in the

Quibéron mutinies, she was renamed to

Redoutable. She took part in the

Croisière du Grand Hiver, the

Battle of Groix, and the

Expédition d'Irlande. At the

Peace of Amiens,

Redoutable was sent to the Caribbean for the

Saint-Domingue expedition, ferrying troops to Guadeloupe and Haiti.

Later, she served in the fleet under Vice-admiral Villeneuve, and took part in the

Trafalgar Campaign. At the

Battle of Trafalgar,

Redoutable rushed to cover the flagship

Bucentaure when the ship following her failed to maintain the line. She tried in vain to stop Nelson's

HMS Victory from breaking the line and raking

Bucentaure, and then engaged her with furious cannon and small arms fire that silenced the British flagship and killed Nelson. As her crew prepared to board

Victory, HMS

Temeraire raked her with grapeshot, killing or maiming most of her crew.

Redoutable continued to fight until she was in danger of sinking before striking her colours. She foundered in the storm of 22 October.

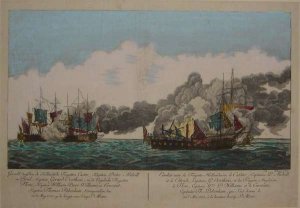

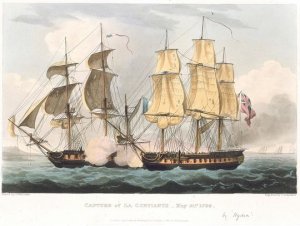

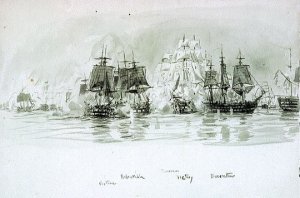

The

Redoutable (centre) fighting the

Temeraire (left) and

HMS Victory (right), by

Louis-Philippe Crépin

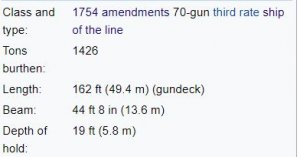

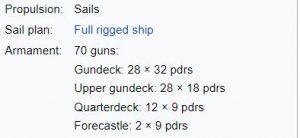

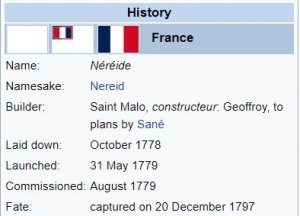

Career

The ship was laid down at Brest in January 1790, and launched as

Suffren on 31 May 1791. She was the first ship of the French Navy named in honour of Vice-admiral

Suffren de Saint Tropez, who had died a hero of the

American War of Independence on 8 December 1788. She was completed there in December 1792.

Quibéron mutinies

Suffren was attached to the Brest fleet under Vice-admiral de Grimouard, later replaced by

Morard de Galles. Under Captain Obet, she departed Brest in 1793 for a cruise to Quibéron. In September, the crews of the fleet revolted in the

Quibéron mutinies, including the crew of

Suffren.

In retaliation,

Suffren was renamed

Redoutable on 20 May 1794. The same day, she received the new naval flag of the Republic, the full tricolour which replaced the white flag with a tricolour canton, and hoisted her.

Service in Brest

From March to June 1794,

Redoutable, under Captain Dorré, was the flagship of the naval station of Cancale. The division of Cancale was under Dorré, and was composed of

Redoutable and her sister-ship

Nestor, under Captain Monnier.

In December, she took part in the

Croisière du Grand Hiver under Captain

Moncousu; upon departure, she broke her cables, but unlike the ill-fated

Républicain, she managed to reach the open sea, followed by the frigate

Vertu. However, the damage sustained in the incident forced her to cancel her departure, and she returned to Brest.

In February 1795,

Redoutable was the flagship of a division under Rear-admiral

Kerguelen within the fleet of Brest, under

Villaret-Joyeuse. Still under Captain Moncousu and with Commander

Bourayne as first officer, she took part in the

Battle of Groix on 23 June 1795, where her poor sailing properties compelled the frigate

Virginie, under Captain

Bergeret, to take her in tow. During the battle, she was one of the few ships of observe

Villaret's orders to support

Alexandre. Later, along with

Tigre, she attempted to support

Formidable, but to no avail as

Formidable's tops caught fire and she ceased all resistance to save herself, eventually striking her colours. After the battle, she sailed back to

Port-Louis, near

Lorient,

In December 1796,

Redoutable took part in the

Expédition d'Irlande under Moncousu, by then promoted to Rear-admiral, and was the first French ship to reach

Bantry Bay, after rallying elements of the French fleet. In the night of 22 to 23 December, she accidentally collided with

Nielly's flagship, the frigate

Résolue, dismasting her of her

bowsprit,

foremast, and

mizzen; only her

mainmast stayed upright. the 74-gun

Pégase took

Résolue in tow and returned with her to Brest, where they arrived on 30 December;

Redoutable eventually limped back to Brest, where she arrived on 5 January 1797, in consort with

Fougueux,

Trajan,

Neptune and

Tourville, and four frigates.

Service in the Caribbean

In March 1802, the

Redoutable was the flagship of a squadron of two

ships of the line and four

frigates under Admiral

Bouvet sent to reinforce

Guadeloupe in 1802 and in the

Saint-Domingue expedition in 1803, departing on 9 January from Ajaccio with troops and arriving on 4 February.

In 1803,

Redoutable, under Captain Siméon, was part of a naval division under Rear-admiral

Bedout, based in Saint-Domingue. The division was composed of the 74-gun

Argonaute as flagship, with Captain Bourdé as Bedout's

flag officer; the 74-guns

Redoutable and

Aigle, under Captain

Gourrège; the frigate

Vertu, under Commander

Montalan; and the corvettes

Serpente, under Commander Gallier-Labrosse, and

Éole, under Lieutenant Descorches.

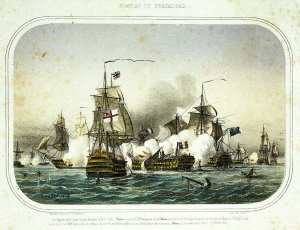

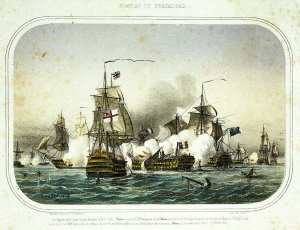

Battle of Trafalgar

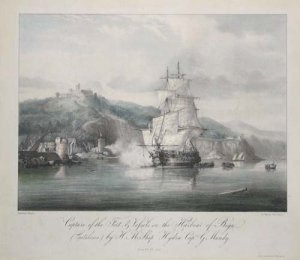

Redoutable

Redoutable (second from left) overtakes

Neptune (far left), rushing to cover the aft of

Bucentaure (far right) from Nelson's

Victory (centre).

Redoutable

Redoutable simultaneously engaged by

Victory and

Temeraire

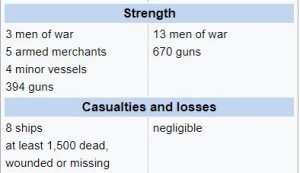

At the

Battle of Trafalgar, on 21 October 1805,

Redoutable was commanded by Captain

Lucas, with Lieutenant

Dupotet as first officer.

Redoutable was the third ship behind the flagship

Bucentaure in the French line, coming behind

Maistral's

Neptune and

Quevedo's

San Leandro. When

Neptune and

San Leandro dropped behind

Bucentaure, exposing her stern,

Redoutable rushed to cover her and prevent Nelson's

Victory from cutting the Franco-Spanish line of battle.

With her bowsprit almost touching

Bucentaure's stern,

Redoutable fired on

Victory's rigging for ten minutes, trying to disable her to prevent the crossing of the French line, but did not manage to stop her advance, despite cutting off her foremast tops, her mizzen and her main topgallant, and ended up running afoul of her. A furious, fifteen-minute musket duel erupted between the two ships; the crew of

Redoutable had been especially trained by Lucas for such an occasion, and soon the heavy hand-grenade and small-arms fire on

Victory's quarterdeck mortally wounded

Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson. Lucas later reported:

a violent small-arms exchange ensued (...); our fire became so superior that within fifteen minutes, we had silenced that of Victory; (...) her castles were covered with dead and wounded, and admiral Nelson was killed by our gunfire. Almost at once, the castles of the enemy ship were evacuated and Victory completely ceased fighting us; but boarding her proved difficult because (...) of her elevated third battery. I ordered the rigging of the great yard be cut and that it be carried to serve as a bridge.

Redoutable

Redoutable during the late stages of the battle, dismasted and attacked by two larger ships.

The French crew were about to board

Victory when

Temeraire intervened, firing on the exposed French crew at point blank range, killing or wounding 200 men, including Lucas and Dupotet, struck by a bullet to the knee, who nevertheless remained at their stations. The crew of

Redoutable rushed to man her artillery and engage

Temeraire with her starboard battery, Soon,

Tonnant took a position at stern of

Redoutable, which thus found herself fired upon from three larger ships. In the ensuing cannonade,

Redoutable lost most of her artillery, including two guns that burst, killing several gunners.

Temeraire hailed for

Redoutable to surrender, but Lucas had volley of musketry fired for replies.

At 1.55 pm,

Redoutable, with Lucas severely wounded, and only 99 men still fit out of 643 (300 dead and 222 severely wounded), was essentially defenceless. The

Fougueux attempted to come to her aid but came afoul of

Temeraire. After ascertaining that

Redoutable was too damaged to survive the aftermath of the battle, and worried that she would sink before his wounded could be evacuated, Lucas struck his colours at 2:30.

Redoutable's aft featured a large opening and was in danger of collapsing, her rudder was shot off, and the hull was pierced in many spots.

Being much damaged and weakened by the fight themselves, the British ships took some time to take possession of

Redoutable, and Lucas had to request urgent assistance to pump water, as four of

Redoutable's pumps were destroyed and few of her crewmen could man them.

Redoutable was freed from the rigging of

Temeraire around 7 in the evening and was taken in tow by

Swiftsure. The next day,

Redoutable made distress signals, and

Swiftsure launched boats to evacuate her passengers; she foundered around 7, taking 196 men with her. Lucas reported:

On the 30th, at 5pm, she was forced to ask for assistance; there was only time to save the captain and the men who were not wounded, as at 7pm, her stern collapsed and she foundered. 50 wounded were saved as they clung to floating debris from the ship.

Victory had sustained 160 casualties, and

Temeraire 120. Of

Redoutable's crew, 169 were taken on board

Swiftsure; the wounded were sent to Cadiz on a

cartel, and 35 men were taken prisoner to England.

Lucas was received in England with great courtesy. After his release from capture, he was personally awarded the rank of Commandeur of the

Legion of Honour by

Napoleon for his role during the battle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Redoutable_(1791)

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org