Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

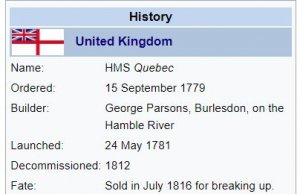

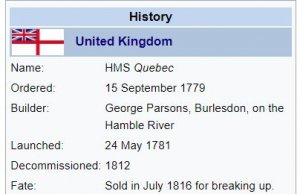

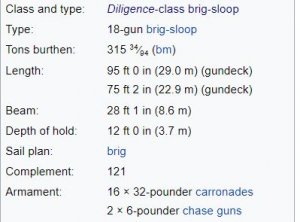

24 May 1781 – Launch of HMS Quebec, a 32-gun fifth rate frigate launched in 1781 and broken up in 1816

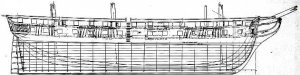

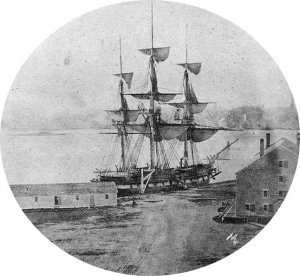

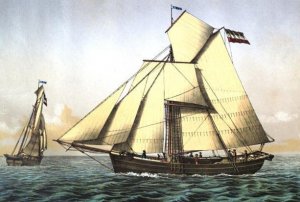

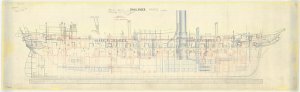

HMS Quebec was a 32-gun fifth rate frigate launched in 1781 and broken up in 1816. She sailed under various captains, participating in the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. During these wars she captured many enemy merchantmen and smaller privateers in northern or Caribbean waters. She was built by George Parsons at Bursledon, Hampshire.

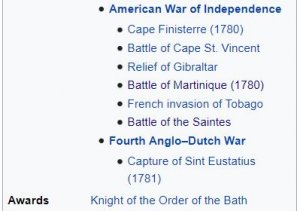

American War of Independence

1782

Capture of the American Frigate South Carolina by the British frigates Diomede, Quebec and Astrea

Throughout 1782, Christopher Mason commanding, HMS Quebec operated in North American waters in the final year of the War of American Independence. On 22 February that year she captured the schooner Betsy, and in April two ships laden with flour, oil, bale goods, salt and wine. On 20 December she was involved when Diomede and Astraea captured the American frigate South Carolina, for which she shared in prize money awarded eighteen months later.

French Revolutionary Wars

1793

Admiral John MacBride became commander-in-chief on the Downs station, commanding a frigate squadron with his flag in Cumberland, later transferring his flag to Quebec. He took possession of Ostend after the French retreat in early 1793, and in October transported reinforcements under General Sir Charles Grey to assist in the defence of Dunkirk. In late October 1793 much needed reinforcements and artillery supplies were landed by Quebec at Nieuport, which was then being besieged by French forces, a relief force from Ostend arrived, and the French withdrew.

1794

From March 1794 a taskforce under Vice-Admiral Sir John Jervis, with land forces under General Sir Charles Grey, operated against French possessions in the Leeward Islands of the Caribbean. Quebecwas an active participant, supplying some of the assault forces at Martinique (late March) where she lost one man killed.[6] St Lucia fell on 4 April, whereupon Quebec (under Captain Josias Rogers), Blanche, Ceres and Rose were ordered to seize the smaller islands, the Saints, which they did without loss on 5 April.

Parts of Guadeloupe fell to the British on 23 April 1794 with Quebec playing her part, and many enemy ships were captured as they attempted to leave the anchorage. Details of prize monies awarded for the capture of engineering and ordnance stores on Martinique, St Lucia and Guadeloupe named Quebec and thirty other warships, plus six gunboats.

On 12 August 1794 a French ship, Adelle, was captured, for which prize money was awarded a year later.

1795

Actions against Grenada the following year did not go so well. Rogers reported on 9 April 1795 persistent heavy rain had caused delays in the military operations on Grenada. Seemingly in desperation, an assault was made on the last stronghold of the French in the mountains, but the French repulsed the attack, causing heavy British casualties.

1796

In 1796, Quebec – now under the command of Captain John Cooke, Rogers having died of yellow fever in April 1795 - was in home waters, reporting from Spithead the capture of a French national cutter Aspic, off the Scilly Isles. Aspic had a crew of 57 men and carried 10 guns. She was 10 days out of Saint-Malo and had captured the sloop John, of and from Galway, sailing to Oporto.

Quebec was soon back in the Caribbean on the Jamaica station. On 3 December 1796 she captured the French corvette ’Affricaine, of 18 guns, near St Domingo.

1797

On 18 April Vice-Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, who commanded the Jamaica station, ordered Captain Hugh Pigot to take his frigate Hermione, as well as the frigates Quebec and Mermaid, the brig Drake and the Hired armed cutter Penelope to cut out 14 vessels at the Battle of Jean-Rabel, Haiti. The squadron rendezvoused the next day and then the boats went in on the night of the 20th. They succeeded in bringing out nine merchant vessels that French privateers had taken as prizes. In the same series of operations the 74-gun ships Thunderer and Valiant destroyed the escorting French frigate, Harmonie.

1799 and 1800

While he commanded at Jamaica, Hyde Parker sent regular reports of warships and merchant vessels captured or destroyed by the ships under his command. At various times from October 1799 to February 1800, Quebec seized American, French or Danish merchant ships bound for ports in the Americas or Caribbean with cargoes as diverse as cocoa, lumber, wine, soap & sundries, flour, sugar, cotton, honey and hides. A Spanish vessel, Nostra Senora del Carmen “laden with fustie and brazil” was captured in March or April. Between May and August 1800, Quebec took captive an armed rowing boat with a crew of 19 men, a small schooner (name unknown) and six small merchant vessels cut out at different times.

1802

When the Treaty of Amiens brought what would turn out to be a temporary peace, the Admiralty took Quebec out of commission. She did not return to active service until 1805.

Napoleonic Wars

1806-7

On 28 May 1806 Quebec and Paulina were in company and shared in the capture of the Frau Geziner.

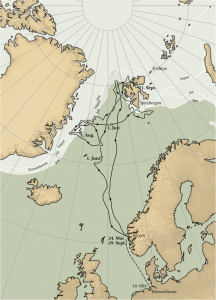

In April 1807 the vessel Providentia fell to Quebec, and between 16 August and 2 September 1807, Quebec and her consorts took nineteen Danish merchant ships. Quebec’s station during this time was in the Downs and North Sea.

1808

On 22 March, while Danish harbours were still largely frozen in, Quebec was operating in the Great Belt and Kattegat as the British navy gathered. The last operating Danish ship-of-the-line was under orders to clear the Great Belt of enemy (British) warships but was closely watched that morning by Quebec, with the sloop Lynx in company. In the early afternoon Falcon joined them in Sejerø Bay, as the Danish ship sailed north and east around Zealand Point. Two hours later the British ships-of-the-line Nassau and Stately were sighted and Quebec and the two sloops observed the ensuing battle without putting themselves in harm's way.

Further information: Battle of Zealand Point

A few days later off Nyborg, a late winter storm dismasted Quebec. Falcon then helped her to erect a new mast and rigging.

1810

In 1810, Quebec was stationed in the North Sea primarily off the Frisian Islands of Texel and Vlie to help enforce the naval blockade of that coast. In March she retook the Susannah Margaretta, and boats from the hired armed cutters Idas and King George, under Quebec’s command, captured a French privateer schyut of four guns, while subject to heavy small arms fire. On 21 March Quebec captured another French privateer, the lugger Imperatrice of 14 guns and 42 men off the Dogger Bank. On 23 May, when Desiree captured Financier, Quebec (under Charles Hawtayne) and Active were in company and shared the prize money.

Also on 23 May, Quebec captured the James Cook. Six days later a cutting out expedition at Vlie with boats from Desireee, Quebec, Britomart and Bold) yielded a French lugger (12), a French privateer (4), a Dutch gunboat and a small rowboat. The British had no casualties; the French lost one man killed and three wounded. On the last day of May, Quebec took three more ships: St Jean Baptiste, Comtessa, and Forben. One more ship was taken on 17 September (Bienenstock) and two ships were recaptured during October 1810 (Jonge Edward and Perle).

On 8 November Quebec cut out a "fine French privateer schooner, La Jeune Louise (14)" from the Vlie Stroom, an area of difficult and shallow navigation.

The year finished with the capture on 2 December of the French privateer cutter Renard, of six guns. Quebec shared the prize money with Kite.

1811

Quebec was still under the command of Captain Hawtayne and on the same station when she recaptured Aquator on 26 May.

In August 1811 in company with 5 lesser warships. Quebec captured a Vaisseau de Guerre of the Imperial Customs Service, later named as a privateer Christine Charlotte, with her crew of one officer and twelve men, as she was leaving Nordeney (East Frisian Islands) with a merchant vessel in tow. Boats from Quebec and her consorts then attacked and after a hard fight captured four French gunboats (numbers 22, 28, 31, 71) in the harbour at Nordeney. Two months later, on 30 October, Quebec was off the Flemish Banks when she captured the privateer Olympia, of ten 18-pounder guns and 78 men, after a long chase. This was the former schooner HMS Olympia.

Fate

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy laid up many of its ships, Quebec among them. She was advertised for sale in April 1816 for breaking up within twelve months: "Lying at Sheerness, Quebec of 32 guns and 700 tons". she was broken up in July.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

24 May 1781 – Launch of HMS Quebec, a 32-gun fifth rate frigate launched in 1781 and broken up in 1816

HMS Quebec was a 32-gun fifth rate frigate launched in 1781 and broken up in 1816. She sailed under various captains, participating in the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. During these wars she captured many enemy merchantmen and smaller privateers in northern or Caribbean waters. She was built by George Parsons at Bursledon, Hampshire.

American War of Independence

1782

Capture of the American Frigate South Carolina by the British frigates Diomede, Quebec and Astrea

Throughout 1782, Christopher Mason commanding, HMS Quebec operated in North American waters in the final year of the War of American Independence. On 22 February that year she captured the schooner Betsy, and in April two ships laden with flour, oil, bale goods, salt and wine. On 20 December she was involved when Diomede and Astraea captured the American frigate South Carolina, for which she shared in prize money awarded eighteen months later.

French Revolutionary Wars

1793

Admiral John MacBride became commander-in-chief on the Downs station, commanding a frigate squadron with his flag in Cumberland, later transferring his flag to Quebec. He took possession of Ostend after the French retreat in early 1793, and in October transported reinforcements under General Sir Charles Grey to assist in the defence of Dunkirk. In late October 1793 much needed reinforcements and artillery supplies were landed by Quebec at Nieuport, which was then being besieged by French forces, a relief force from Ostend arrived, and the French withdrew.

1794

From March 1794 a taskforce under Vice-Admiral Sir John Jervis, with land forces under General Sir Charles Grey, operated against French possessions in the Leeward Islands of the Caribbean. Quebecwas an active participant, supplying some of the assault forces at Martinique (late March) where she lost one man killed.[6] St Lucia fell on 4 April, whereupon Quebec (under Captain Josias Rogers), Blanche, Ceres and Rose were ordered to seize the smaller islands, the Saints, which they did without loss on 5 April.

Parts of Guadeloupe fell to the British on 23 April 1794 with Quebec playing her part, and many enemy ships were captured as they attempted to leave the anchorage. Details of prize monies awarded for the capture of engineering and ordnance stores on Martinique, St Lucia and Guadeloupe named Quebec and thirty other warships, plus six gunboats.

On 12 August 1794 a French ship, Adelle, was captured, for which prize money was awarded a year later.

1795

Actions against Grenada the following year did not go so well. Rogers reported on 9 April 1795 persistent heavy rain had caused delays in the military operations on Grenada. Seemingly in desperation, an assault was made on the last stronghold of the French in the mountains, but the French repulsed the attack, causing heavy British casualties.

1796

In 1796, Quebec – now under the command of Captain John Cooke, Rogers having died of yellow fever in April 1795 - was in home waters, reporting from Spithead the capture of a French national cutter Aspic, off the Scilly Isles. Aspic had a crew of 57 men and carried 10 guns. She was 10 days out of Saint-Malo and had captured the sloop John, of and from Galway, sailing to Oporto.

Quebec was soon back in the Caribbean on the Jamaica station. On 3 December 1796 she captured the French corvette ’Affricaine, of 18 guns, near St Domingo.

1797

On 18 April Vice-Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, who commanded the Jamaica station, ordered Captain Hugh Pigot to take his frigate Hermione, as well as the frigates Quebec and Mermaid, the brig Drake and the Hired armed cutter Penelope to cut out 14 vessels at the Battle of Jean-Rabel, Haiti. The squadron rendezvoused the next day and then the boats went in on the night of the 20th. They succeeded in bringing out nine merchant vessels that French privateers had taken as prizes. In the same series of operations the 74-gun ships Thunderer and Valiant destroyed the escorting French frigate, Harmonie.

1799 and 1800

While he commanded at Jamaica, Hyde Parker sent regular reports of warships and merchant vessels captured or destroyed by the ships under his command. At various times from October 1799 to February 1800, Quebec seized American, French or Danish merchant ships bound for ports in the Americas or Caribbean with cargoes as diverse as cocoa, lumber, wine, soap & sundries, flour, sugar, cotton, honey and hides. A Spanish vessel, Nostra Senora del Carmen “laden with fustie and brazil” was captured in March or April. Between May and August 1800, Quebec took captive an armed rowing boat with a crew of 19 men, a small schooner (name unknown) and six small merchant vessels cut out at different times.

1802

When the Treaty of Amiens brought what would turn out to be a temporary peace, the Admiralty took Quebec out of commission. She did not return to active service until 1805.

Napoleonic Wars

1806-7

On 28 May 1806 Quebec and Paulina were in company and shared in the capture of the Frau Geziner.

In April 1807 the vessel Providentia fell to Quebec, and between 16 August and 2 September 1807, Quebec and her consorts took nineteen Danish merchant ships. Quebec’s station during this time was in the Downs and North Sea.

1808

On 22 March, while Danish harbours were still largely frozen in, Quebec was operating in the Great Belt and Kattegat as the British navy gathered. The last operating Danish ship-of-the-line was under orders to clear the Great Belt of enemy (British) warships but was closely watched that morning by Quebec, with the sloop Lynx in company. In the early afternoon Falcon joined them in Sejerø Bay, as the Danish ship sailed north and east around Zealand Point. Two hours later the British ships-of-the-line Nassau and Stately were sighted and Quebec and the two sloops observed the ensuing battle without putting themselves in harm's way.

Further information: Battle of Zealand Point

A few days later off Nyborg, a late winter storm dismasted Quebec. Falcon then helped her to erect a new mast and rigging.

1810

In 1810, Quebec was stationed in the North Sea primarily off the Frisian Islands of Texel and Vlie to help enforce the naval blockade of that coast. In March she retook the Susannah Margaretta, and boats from the hired armed cutters Idas and King George, under Quebec’s command, captured a French privateer schyut of four guns, while subject to heavy small arms fire. On 21 March Quebec captured another French privateer, the lugger Imperatrice of 14 guns and 42 men off the Dogger Bank. On 23 May, when Desiree captured Financier, Quebec (under Charles Hawtayne) and Active were in company and shared the prize money.

Also on 23 May, Quebec captured the James Cook. Six days later a cutting out expedition at Vlie with boats from Desireee, Quebec, Britomart and Bold) yielded a French lugger (12), a French privateer (4), a Dutch gunboat and a small rowboat. The British had no casualties; the French lost one man killed and three wounded. On the last day of May, Quebec took three more ships: St Jean Baptiste, Comtessa, and Forben. One more ship was taken on 17 September (Bienenstock) and two ships were recaptured during October 1810 (Jonge Edward and Perle).

On 8 November Quebec cut out a "fine French privateer schooner, La Jeune Louise (14)" from the Vlie Stroom, an area of difficult and shallow navigation.

The year finished with the capture on 2 December of the French privateer cutter Renard, of six guns. Quebec shared the prize money with Kite.

1811

Quebec was still under the command of Captain Hawtayne and on the same station when she recaptured Aquator on 26 May.

In August 1811 in company with 5 lesser warships. Quebec captured a Vaisseau de Guerre of the Imperial Customs Service, later named as a privateer Christine Charlotte, with her crew of one officer and twelve men, as she was leaving Nordeney (East Frisian Islands) with a merchant vessel in tow. Boats from Quebec and her consorts then attacked and after a hard fight captured four French gunboats (numbers 22, 28, 31, 71) in the harbour at Nordeney. Two months later, on 30 October, Quebec was off the Flemish Banks when she captured the privateer Olympia, of ten 18-pounder guns and 78 men, after a long chase. This was the former schooner HMS Olympia.

Fate

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy laid up many of its ships, Quebec among them. She was advertised for sale in April 1816 for breaking up within twelve months: "Lying at Sheerness, Quebec of 32 guns and 700 tons". she was broken up in July.

of Lütjens' decision was received with shock in Berlin,

of Lütjens' decision was received with shock in Berlin,

s continued throughout the night. The following day Antelope was still afloat, but her keel had broken and her superstructure melted into a heap of twisted metal. Antelope broke in half and sank that day. TV and still pictures of Antelope's demise became one of the iconic images of the

s continued throughout the night. The following day Antelope was still afloat, but her keel had broken and her superstructure melted into a heap of twisted metal. Antelope broke in half and sank that day. TV and still pictures of Antelope's demise became one of the iconic images of the