Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

22 May 853 – Sack of Damietta

A Byzantine fleet sacks and destroys undefended Damietta in Egypt.

The Sack of Damietta was a successful raid on the port city of Damietta on the Nile Delta by the Byzantine navy on 22–24 May 853. The city, whose garrison was absent at the time, was sacked and plundered, yielding not only many captives but also large quantities of weapons and supplies intended for the Emirate of Crete. The Byzantine attack, which was repeated in the subsequent years, shocked the Abbasid authorities, and urgent measures were taken to refortify the coasts and strengthen the local fleet, beginning a revival of the Egyptian navy that culminated in the Tulunid and Fatimid periods.

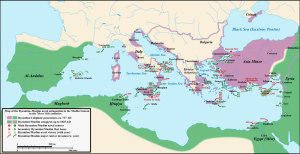

Map of the Arab–Byzantine naval conflict in the Mediterranean, 7th–11th centuries

Background

During the 820s, the Byzantine Empire suffered two great losses that destroyed their naval supremacy in the Mediterranean: the beginning of the Muslim conquest of Sicily and the fall of Crete to Andalusian exiles. These losses ushered in an era where Saracen pirates raided the Christian northern shores of the Mediterranean almost at will. The establishment of the Emirate of Crete, which became a haven for Muslim ships, opened the Aegean Sea up for raids, while their—albeit partial—control of Sicily allowed the Arabs to raid and even settle in Italy and the Adriatic shores. Several Byzantine attempts to retake Crete in the immediate aftermath of the Andalusian conquest, as well as a large-scale invasion in 842/43, failed with heavy losses.

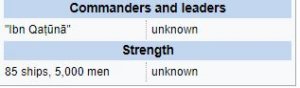

Byzantine expedition against Damietta

In 853 the Byzantine government tried a new approach: instead of attacking Crete directly, they tried to sever the island's lines of supply, principally to Egypt, which was, in the words of Alexander Vasiliev, "the arsenal of the Cretan pirates". The Arab historian al-Tabari reports that three fleets, totalling almost 300 ships, were prepared and sent on simultaneous raids of Muslim naval bases in the Eastern Mediterranean. The precise targets of the first two fleets are unknown, but the third, comprising 85 ships and 5,000 men under a commander known from Arab sources only as "Ibn Qaṭūnā", headed for the Egyptian coast.

Various identifications have been proposed by modern scholars for "Ibn Qaṭūnā", but without any firm evidence. Based on the similarity of consonants in their names, Henri Grégoire variously suggested an identification with Sergios Niketiates, who however probably died in 843, and with Constantine Kontomytes. In a later work in 1952 he suggested that he might be identified with the parakoimomenos Damian, considering the Arabic name a rendering of the Byzantine title epi tou koitonos ("in charge of the imperial bedchamber"). Previously, in 1913, the Syriac scholar E. W. Brooks had suggested an identification with the strategos Photeinos.

Egyptian naval defences were weak. The Egyptian fleet had declined from its Umayyad-era peak and was mostly employed in the Nile rather than in the Mediterranean. Fortifications along the coastal marshes, which had been manned by volunteer garrisons, had been abandoned in the later 8th century. The Byzantines had exploited this in 811/12 and again in c. 815, launching raids against the coasts of Egypt. The Byzantine fleet arrived at Damietta on 22 May 853. The city garrison were absent at a feast for the Day of Arafah, organized by the governor Anbasah ibn Ishaq al-Dabbi in Fustat. Damietta's inhabitants fled the undefended city, which was plundered for two days and then torched by the Byzantine troops. The Byzantines carried off some six hundred Arab and Coptic women, as well as large quantities of arms and other supplies intended for Crete. The fleet then sailed east and attacked the strong fortress of Ushtun. Upon taking it, they burned the many artillery and siege engines found there before returning home.

Aftermath and impact

Although the raid at Damietta was, according to historian Vassilios Christides, "one of the brightest military operations" undertaken by the Byzantine military, it is completely ignored in Byzantine sources, probably because most accounts are warped by their hostile attitude to Michael III (r. 842–867) and his reign. As a result, the raid is known only through two Arab accounts, by al-Tabari and Ya'qubi.

The Byzantines returned and raided Damietta again in 854. Another raid possibly took place in 855, as the Arabic sources indicate that the arrival of a Byzantine fleet in Egypt was anticipated by the Abbasid authorities. In 859, the Byzantine fleet attacked Farama. Despite these successes, Saracen piracy in the Aegean continued unabated, and reached its height in the early 900s, with the sack of Thessalonica, the Byzantine Empire's second city, in 904, and the activities of the renegades Leo of Tripoli and Damian of Tarsus. It would not be until 961 that the Byzantines reconquered Crete, and secured control of the Aegean.

In the more immediate aftermath, according to the Arab chroniclers, the raid led to the realization of Egypt's vulnerability from the sea. After a long period of neglect, Egypt's maritime defences were urgently strengthened by Governor Anbasah. Within nine months of the raid, Damietta was refortified, along with Tinnis and Alexandria. Various works were undertaken at Rosetta, Borollos, Ashmun, at-Tina, and Nastarawwa, while ships were constructed and new crews raised. Most seamen were forcibly conscripted from among the Copts and the Arabs of the interior, which earned Anbasah a bad reputation in contemporary sources, and complaints against him were directed to Caliph al-Mutawakkil. Later Arabic sources like al-Maqrizi and Coptic sources confirm that the new fleet was used in raids against the Byzantines in subsequent years, although no details are recorded. This activity is generally held to have marked the rebirth of the Egyptian navy, which came to number 100 ships under the Tulunid dynasty (868–905) and reached its peak later under the Fatimids (969–1171).

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

22 May 853 – Sack of Damietta

A Byzantine fleet sacks and destroys undefended Damietta in Egypt.

The Sack of Damietta was a successful raid on the port city of Damietta on the Nile Delta by the Byzantine navy on 22–24 May 853. The city, whose garrison was absent at the time, was sacked and plundered, yielding not only many captives but also large quantities of weapons and supplies intended for the Emirate of Crete. The Byzantine attack, which was repeated in the subsequent years, shocked the Abbasid authorities, and urgent measures were taken to refortify the coasts and strengthen the local fleet, beginning a revival of the Egyptian navy that culminated in the Tulunid and Fatimid periods.

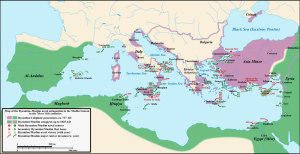

Map of the Arab–Byzantine naval conflict in the Mediterranean, 7th–11th centuries

Background

During the 820s, the Byzantine Empire suffered two great losses that destroyed their naval supremacy in the Mediterranean: the beginning of the Muslim conquest of Sicily and the fall of Crete to Andalusian exiles. These losses ushered in an era where Saracen pirates raided the Christian northern shores of the Mediterranean almost at will. The establishment of the Emirate of Crete, which became a haven for Muslim ships, opened the Aegean Sea up for raids, while their—albeit partial—control of Sicily allowed the Arabs to raid and even settle in Italy and the Adriatic shores. Several Byzantine attempts to retake Crete in the immediate aftermath of the Andalusian conquest, as well as a large-scale invasion in 842/43, failed with heavy losses.

Byzantine expedition against Damietta

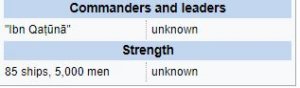

In 853 the Byzantine government tried a new approach: instead of attacking Crete directly, they tried to sever the island's lines of supply, principally to Egypt, which was, in the words of Alexander Vasiliev, "the arsenal of the Cretan pirates". The Arab historian al-Tabari reports that three fleets, totalling almost 300 ships, were prepared and sent on simultaneous raids of Muslim naval bases in the Eastern Mediterranean. The precise targets of the first two fleets are unknown, but the third, comprising 85 ships and 5,000 men under a commander known from Arab sources only as "Ibn Qaṭūnā", headed for the Egyptian coast.

Various identifications have been proposed by modern scholars for "Ibn Qaṭūnā", but without any firm evidence. Based on the similarity of consonants in their names, Henri Grégoire variously suggested an identification with Sergios Niketiates, who however probably died in 843, and with Constantine Kontomytes. In a later work in 1952 he suggested that he might be identified with the parakoimomenos Damian, considering the Arabic name a rendering of the Byzantine title epi tou koitonos ("in charge of the imperial bedchamber"). Previously, in 1913, the Syriac scholar E. W. Brooks had suggested an identification with the strategos Photeinos.

Egyptian naval defences were weak. The Egyptian fleet had declined from its Umayyad-era peak and was mostly employed in the Nile rather than in the Mediterranean. Fortifications along the coastal marshes, which had been manned by volunteer garrisons, had been abandoned in the later 8th century. The Byzantines had exploited this in 811/12 and again in c. 815, launching raids against the coasts of Egypt. The Byzantine fleet arrived at Damietta on 22 May 853. The city garrison were absent at a feast for the Day of Arafah, organized by the governor Anbasah ibn Ishaq al-Dabbi in Fustat. Damietta's inhabitants fled the undefended city, which was plundered for two days and then torched by the Byzantine troops. The Byzantines carried off some six hundred Arab and Coptic women, as well as large quantities of arms and other supplies intended for Crete. The fleet then sailed east and attacked the strong fortress of Ushtun. Upon taking it, they burned the many artillery and siege engines found there before returning home.

Aftermath and impact

Although the raid at Damietta was, according to historian Vassilios Christides, "one of the brightest military operations" undertaken by the Byzantine military, it is completely ignored in Byzantine sources, probably because most accounts are warped by their hostile attitude to Michael III (r. 842–867) and his reign. As a result, the raid is known only through two Arab accounts, by al-Tabari and Ya'qubi.

The Byzantines returned and raided Damietta again in 854. Another raid possibly took place in 855, as the Arabic sources indicate that the arrival of a Byzantine fleet in Egypt was anticipated by the Abbasid authorities. In 859, the Byzantine fleet attacked Farama. Despite these successes, Saracen piracy in the Aegean continued unabated, and reached its height in the early 900s, with the sack of Thessalonica, the Byzantine Empire's second city, in 904, and the activities of the renegades Leo of Tripoli and Damian of Tarsus. It would not be until 961 that the Byzantines reconquered Crete, and secured control of the Aegean.

In the more immediate aftermath, according to the Arab chroniclers, the raid led to the realization of Egypt's vulnerability from the sea. After a long period of neglect, Egypt's maritime defences were urgently strengthened by Governor Anbasah. Within nine months of the raid, Damietta was refortified, along with Tinnis and Alexandria. Various works were undertaken at Rosetta, Borollos, Ashmun, at-Tina, and Nastarawwa, while ships were constructed and new crews raised. Most seamen were forcibly conscripted from among the Copts and the Arabs of the interior, which earned Anbasah a bad reputation in contemporary sources, and complaints against him were directed to Caliph al-Mutawakkil. Later Arabic sources like al-Maqrizi and Coptic sources confirm that the new fleet was used in raids against the Byzantines in subsequent years, although no details are recorded. This activity is generally held to have marked the rebirth of the Egyptian navy, which came to number 100 ships under the Tulunid dynasty (868–905) and reached its peak later under the Fatimids (969–1171).