Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

23 May 1701 – After being convicted of piracy and of murdering William Moore, Captain William Kidd is hanged in London.

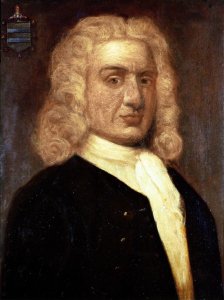

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd (c. 1654 – 23 May 1701), was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians, for example Sir Cornelius Neale Dalton (see Books), deem his piratical reputation unjust.

Captain Kidd in New York Harbor, in a c. 1920 painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

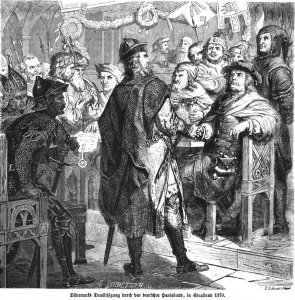

Trial and execution

Captain Kidd, gibbeted, following his execution in 1701.

Prior to returning to New York City, Kidd knew that he was a wanted pirate, and that several English men-of-war were searching for him. Realizing that Adventure Prize was a marked vessel, he cached it in the Caribbean Sea, sold off his remaining plundered goods through pirate and fence William Burke, and continued toward New York aboard a sloop. He deposited some of his treasure on Gardiners Island, hoping to use his knowledge of its location as a bargaining tool.[citation needed] Kidd found himself in Oyster Bay, as a way of avoiding his mutinous crew who gathered in New York. In order to avoid them, Kidd sailed 120 nautical miles (220 km; 140 mi) around the eastern tip of Long Island, and then doubled back 90 nautical miles (170 km; 100 mi) along the Sound to Oyster Bay. He felt this was a safer passage than the highly trafficked Narrows between Staten Island and Brooklyn.

Bellomont (an investor) was away in Boston, Massachusetts. Aware of the accusations against Kidd, Bellomont was justifiably afraid of being implicated in piracy himself, and knew that presenting Kidd to England in chains was his best chance to save himself. He lured Kidd into Boston with false promises of clemency, then ordered him arrested on 6 July 1699. Kidd was placed in Stone Prison, spending most of the time in solitary confinement. His wife, Sarah, was also imprisoned. The conditions of Kidd's imprisonment were extremely harsh, and appear to have driven him at least temporarily insane.[citation needed] By then, Bellomont had turned against Kidd and other pirates, writing that the inhabitants of Long Island were "a lawless and unruly people" protecting pirates who had "settled among them".

After over a year, Kidd was sent to England for questioning by the Parliament of England.[citation needed] The new Tory ministry hoped to use Kidd as a tool to discredit the Whigs who had backed him, but Kidd refused to name names, naively confident his patrons would reward his loyalty by interceding on his behalf. There is speculation that he probably would have been spared had he talked. Finding Kidd politically useless, the Tory leaders sent him to stand trial before the High Court of Admiralty in London, for the charges of piracy on high seas and the murder of William Moore. Whilst awaiting trial, Kidd was confined in the infamous Newgate Prison, and wrote several letters to King William requesting clemency.

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defence. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at Execution Dock, Wapping, in London. He was hanged two times. On the first attempt, the hangman's rope broke and Kidd survived. Although some in the crowd called for Kidd's release, claiming the breaking of the rope was a sign from God, Kidd was hanged again minutes later, this time successfully. His body was gibbeted over the River Thamesat Tilbury Point – as a warning to future would-be pirates – for three years.

Kidd's associates Richard Barleycorn, Robert Lamley, William Jenkins, Gabriel Loffe, Able Owens, and Hugh Parrot were also convicted, but pardoned just prior to hanging at Execution Dock.

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early twentieth century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes call the extent of Kidd's guilt into question. Along with the papers, many goods were brought from the ships and soon auctioned off as "pirate plunder". They were never mentioned in the trial.[citation needed]

As to the accusations of murdering Moore, on this he was mostly sunk on the testimony of the two former crew members, Palmer and Bradinham, who testified against him in exchange for pardons. A deposition Palmer gave, when he was captured in Rhode Island two years earlier, contradicted his testimony and may have supported Kidd's assertions, but Kidd was unable to obtain the deposition.

A broadside song "Captain Kidd's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament" was printed shortly after his execution and popularised the common belief that Kidd had confessed to the charges.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Kidd

23 May 1701 – After being convicted of piracy and of murdering William Moore, Captain William Kidd is hanged in London.

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd (c. 1654 – 23 May 1701), was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians, for example Sir Cornelius Neale Dalton (see Books), deem his piratical reputation unjust.

Captain Kidd in New York Harbor, in a c. 1920 painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

Trial and execution

Captain Kidd, gibbeted, following his execution in 1701.

Prior to returning to New York City, Kidd knew that he was a wanted pirate, and that several English men-of-war were searching for him. Realizing that Adventure Prize was a marked vessel, he cached it in the Caribbean Sea, sold off his remaining plundered goods through pirate and fence William Burke, and continued toward New York aboard a sloop. He deposited some of his treasure on Gardiners Island, hoping to use his knowledge of its location as a bargaining tool.[citation needed] Kidd found himself in Oyster Bay, as a way of avoiding his mutinous crew who gathered in New York. In order to avoid them, Kidd sailed 120 nautical miles (220 km; 140 mi) around the eastern tip of Long Island, and then doubled back 90 nautical miles (170 km; 100 mi) along the Sound to Oyster Bay. He felt this was a safer passage than the highly trafficked Narrows between Staten Island and Brooklyn.

Bellomont (an investor) was away in Boston, Massachusetts. Aware of the accusations against Kidd, Bellomont was justifiably afraid of being implicated in piracy himself, and knew that presenting Kidd to England in chains was his best chance to save himself. He lured Kidd into Boston with false promises of clemency, then ordered him arrested on 6 July 1699. Kidd was placed in Stone Prison, spending most of the time in solitary confinement. His wife, Sarah, was also imprisoned. The conditions of Kidd's imprisonment were extremely harsh, and appear to have driven him at least temporarily insane.[citation needed] By then, Bellomont had turned against Kidd and other pirates, writing that the inhabitants of Long Island were "a lawless and unruly people" protecting pirates who had "settled among them".

After over a year, Kidd was sent to England for questioning by the Parliament of England.[citation needed] The new Tory ministry hoped to use Kidd as a tool to discredit the Whigs who had backed him, but Kidd refused to name names, naively confident his patrons would reward his loyalty by interceding on his behalf. There is speculation that he probably would have been spared had he talked. Finding Kidd politically useless, the Tory leaders sent him to stand trial before the High Court of Admiralty in London, for the charges of piracy on high seas and the murder of William Moore. Whilst awaiting trial, Kidd was confined in the infamous Newgate Prison, and wrote several letters to King William requesting clemency.

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defence. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at Execution Dock, Wapping, in London. He was hanged two times. On the first attempt, the hangman's rope broke and Kidd survived. Although some in the crowd called for Kidd's release, claiming the breaking of the rope was a sign from God, Kidd was hanged again minutes later, this time successfully. His body was gibbeted over the River Thamesat Tilbury Point – as a warning to future would-be pirates – for three years.

Kidd's associates Richard Barleycorn, Robert Lamley, William Jenkins, Gabriel Loffe, Able Owens, and Hugh Parrot were also convicted, but pardoned just prior to hanging at Execution Dock.

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early twentieth century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes call the extent of Kidd's guilt into question. Along with the papers, many goods were brought from the ships and soon auctioned off as "pirate plunder". They were never mentioned in the trial.[citation needed]

As to the accusations of murdering Moore, on this he was mostly sunk on the testimony of the two former crew members, Palmer and Bradinham, who testified against him in exchange for pardons. A deposition Palmer gave, when he was captured in Rhode Island two years earlier, contradicted his testimony and may have supported Kidd's assertions, but Kidd was unable to obtain the deposition.

A broadside song "Captain Kidd's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament" was printed shortly after his execution and popularised the common belief that Kidd had confessed to the charges.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Kidd

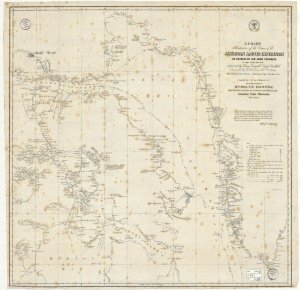

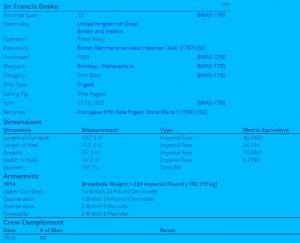

of other concurrent British expeditions was exchanged. On the 21st, they encountered the Felix, under the command of Sir

of other concurrent British expeditions was exchanged. On the 21st, they encountered the Felix, under the command of Sir