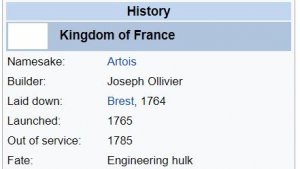

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

8 April 1740 - The Action of 8 April 1740

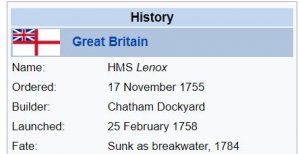

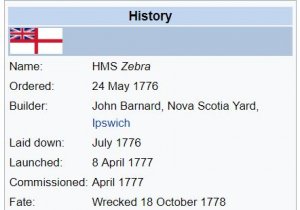

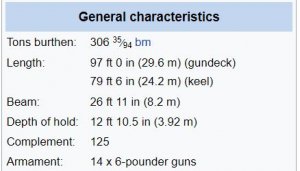

British squadron of HMS Lennox (70), Cptn. Colvill Mayne, HMS Kent (70), Cptn. Durell, and HMS Orford (70), Cptn. Lord Augustus FitzRoy, captured Spanish Princesa (64), Don Parlo Augustino de Gera, off Cape Finisterre

The

Action of 8 April 1740 was a battle between the Spanish

third rate Princesa (nominally rated at 70 guns, but carrying 64) under the command of

Don Parlo Augustino de Gera, and a squadron consisting of three British 70-gun third rates;

HMS Kent,

HMS Lenox and

HMS Orford, under the command of Captain Colvill Mayne of

Lenox. The Spanish ship was chased down and captured by the three British ships, after which she was acquired for service by the

Royal Navy.

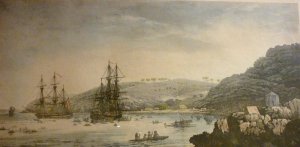

The 70-gun Spanish ship of the line

Princesa in battle with HMS

Lenox,

Kent and

Oxford, 8 April 1740

Museo Naval de Madrid

Background

On 25 March 1740 news reached the

Admiralty that two Spanish ships had sailed from

Buenos Aires, and were bound for Spain. Word was sent to

Portsmouth and a squadron of three ships, consisting of the 70-gun ships

HMS Kent,

HMS Lenox and

HMS Orford, under the command of Captain Colvill Mayne of

Lenox, were prepared to intercept them. The ships, part of

Sir John Balchen's fleet were briefly joined by

HMS Rippon and

HMS St Albans, and the squadron sailed from Portsmouth at 3am on 29 March, passing down the

English Channel.

Rippon and

St Albans fell astern on 5 April, and though Mayne shortened sail, they did not come up. On 8 April Mayne's squadron was patrolling some 300 miles south-west of

The Lizard when a ship was sighted to the north.

Battle

Battle

The British came up and found her to be the

Princesa, carrying 64 guns and a crew of 650 under the command of Don Parlo Augustino de Gera. They began to chase her at 10am, upon which she lowered the French colours she had been flying and hoisted Spanish ones. Mayne addressed his men saying 'When you received the pay of your country, you engaged yourselves to stand all dangers in her cause. Now is the trial; fight like men for you have no hope but in your courage.' After a two and half hour chase the British were able to come alongside and exchange broadsides, which eventually left the Spanish ship disabled. The British then raked her until she

struck her colours. The Spanish ship had casualties of 33 killed and around 100 wounded, while eight men were killed aboard

Kent, another eight aboard

Orford, and another one aboard

Lenox. Total British wounded amounted to 40, and included Captain Durell of

Kent, who had one of his hands shot away.

According to the Spanish version of the facts, the ship Princesa was previously damaged before the battle. The Princesa started a hard battle against the three English ships chasing her. The combat lasted 6 hours. The Princesa seriously damaged one of the English ships (HMS Lenox) and put another one (HMS Kent) on the run, but could not face the battle against the third enemy ship (HMS Oxford) and had to surrender. On board of the Princesa there were 70 dead and 80 injured, and the ship was taken to Portsmouth, where she was repaired and used by the Royal Navy.

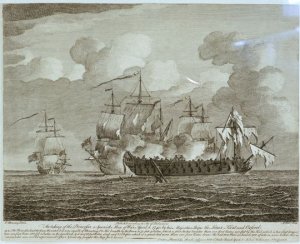

The action from an engraving of a work by Peter Monamy

The action from an engraving of a work by Peter Monamy

Text in English below image: 'The taking of the Princessa [sic] a Spanish Man of War, April 8, 1740, by his Majesties Ships the Lenox, Kent and Oxford. / N.B. The Princessa had 68 guns mounted, but was capable of mounting 86. Her breadth by the beam is 50 feet 4 inches which is four Inches broader than our first Rates: 152 foot by the Keel, which is two foot longer / than our first Rates: 166 foot 3 inches on the Gun Deck, & draws 26 foot Water abaft and 23 1/2 before which is a great deal more than our first Rates draw. She had 600 Men on board of whom 200 were killed. Her / Commander was an Old experience Officer & bravely fought the Ship for 6 hours.

Aftermath

Princesa was brought into Portsmouth on 8 May 1740. An Admiralty order of 21 April 1741 authorised her purchase, and this was duly done on 14 July 1741 for the sum of £5,418.11.6¾d. After a great repair she was fitted at Portsmouth between July 1741 and March 1742, for a total sum of £36,007.2.10d. Her spirited resistance to three ships of equal rating attracted much comment. A contemporary description noted that she was larger than any British

first rate and carried unusually large guns, many of them brass. She was described as the finest ship in the Spanish Navy, with her high build allowing her to open her lower gunports in conditions that meant that her opponents could not. She was renamed

HMS Princess and served in the Royal Navy until she was finally sold for breaking up on 30 December 1784 at

Portsmouth.

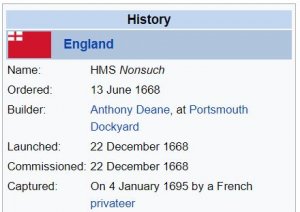

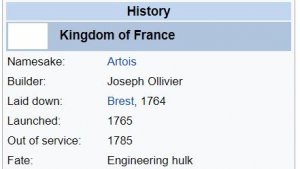

HMS Princess was a 70-gun

third rate ship of the line of the

Royal Navy. She had briefly sailed as

Princesa for the

Spanish Navy, until her capture off

Cape Finisterre in 1740 during the

War of the Austrian Succession.

After being chased down and captured by three British ships, she was acquired for service by the Royal Navy. Her design and fighting qualities excited considerable interest, and sparked a series of increases in the dimensions of British warships. She went on to serve under a number of commanders in several theatres of the War of the Austrian Succession, including the Mediterranean, where she was at the

Battle of Toulon, and in the

Caribbean and off the North American coast. She was then laid up and being assessed, was not reactivated for service during the

Seven Years' War. She was instead reduced to a

hulk at

Portsmouth, in which capacity she lasted out both the Seven Years' War and the

American War of Independence, being sold for breaking up in 1784, shortly after the end of the latter conflict, after a career in British service lasting 44 years.

Spanish career and capture

Princesa

Princesa was built between 1730 and 1731, being nominally rated at 70 guns, but carrying 64.

[1] On 25 March 1740 news reached the

Admiralty that two Spanish ships had sailed from

Buenos Aires, and were bound for Spain. Word was sent to

Portsmouth and a squadron of three ships, consisting of the 70-gun ships

HMS Kent,

HMS Lenox and

HMS Orford, under the command of Captain Colvill Mayne of

Lenox, were prepared to intercept them. The ships, part of

Sir John Balchen's fleet were briefly joined by

HMS Rippon and

HMS St Albans, and the squadron sailed from Portsmouth at 3 am on 29 March, passing down the

English Channel.

Rippon and

St Albans fell astern on 5 April, and though Mayne shortened sail, they did not come up. On 8 April Mayne's squadron was patrolling some 300 miles south-west of

The Lizard when a ship was sighted to the north.

The British came up and found her to be

Princesa, carrying 64 guns and a crew of 650 under the command of Don Parlo Augustino de Gera. They began to chase her at 10 am, upon which she lowered the French colours she had been flying and hoisted Spanish ones. Mayne addressed his men saying 'When you received the pay of your country, you engaged yourselves to stand all dangers in her cause. Now is the trial; fight like men for you have no hope but in your courage.' After a chase lasting two and a half hours, the British were able to come alongside and exchange broadsides, which eventually left the Spanish ship disabled. The British then raked her until she

struck her colours. The Spanish ship had casualties of 33 killed and around 100 wounded, while eight men were killed aboard both

Kent and

Orford, and another one aboard

Lenox. Total British wounded amounted to 40, and included Captain Durell of

Kent, who had one of his hands shot away. The commander of

Orford during the engagement had been

Lord Augustus FitzRoy.

According to the Spanish version of the facts, the ship

Princesa was seriously damaged before the combat. The Spanish ship

Princesa begun a hard battle against the three English ships chasing her. The combat lasted six hours.

Princesa caused serious damages to

Lenox and obliged

Kent to leave the battle, but could not face the encounter against

Orford and surrendered. There were 70 killed and 80 wounded on board

Princesa, which was taken to Portsmouth for reparation. Afterward, she was used by the Royal Navy.

British service

Princesa was brought into Portsmouth on 8 May 1740. An Admiralty order of 21 April 1741 authorised her purchase, and this was duly done on 14 July 1741 for the sum of £5,418.11.6¾d. After a great repair she was fitted at Portsmouth between July 1741 and March 1742, for a total sum of £36,007.2.10d. Her spirited resistance to three ships of equal rating attracted much comment. A contemporary description noted that she was larger than any British

first rate and carried unusually large guns, many of them brass. She was described as the finest ship in the Spanish Navy, with her high build allowing her to open her lower gunports in conditions in which her opponents could not. The Admiralty finally had the ammunition to rouse Parliament from its complacency and fund a series of increases in British warship dimensions.

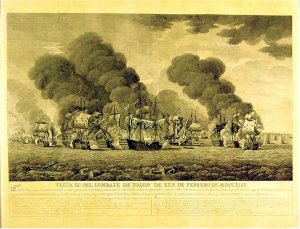

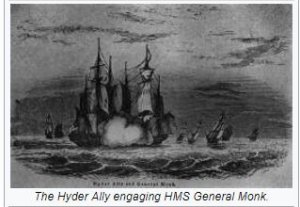

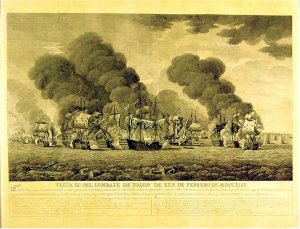

Engraving of the

Battle of Toulon

Princess was commissioned under her first commander, Captain Perry Mayne, in July 1741. He was succeeded in 1743 by Captain Robert Pett, who took her out to the

Mediterranean in December that year. She was part of Admiral

Thomas Mathews' fleet at the

Battle of Toulon on 14 February 1744. She came under the temporary command of Commander John Donkley in July 1745, though he was soon replaced by Captain Joseph Lingen, all the while continuing in the Mediterranean. Thomas Philpot took command in 1746, and

Princess sailed for the

Leeward Islands with Admiral

George Townshend. Captain John Cokburne took over in July 1746 and

Princess first sailed to

Louisbourg and then home after a gale. She became the

flagship of Admiral

Richard Lestock later in 1746 and was present at the operations off

Lorient from 20 to 25 September 1746. In May 1747 Captain

the Hon. Augustus Hervey took over command, and sailed to the Mediterranean, where in October 1747 she briefly became the flagship of Vice-Admiral

John Byng.

Later years

Princess was paid off in November 1748. She was surveyed the following year, but no repairs were reported. After a period laid up and inactive, she was reported to be unfit for service on 15 November 1755; she was converted to a

hulk at Portsmouth between August 1759 and July 1761. She was recommissioned in 1759 under Captain Edward Barber, and continued as a hulk during the

Seven Years' War and the

American War of Independence.

Princess was finally sold at Portsmouth on 30 December 1784.

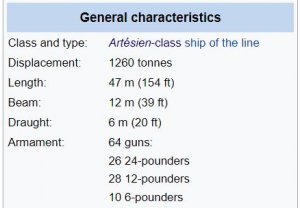

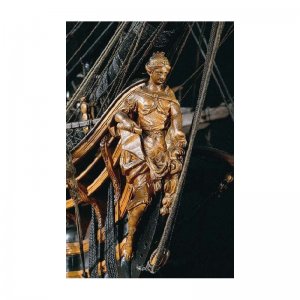

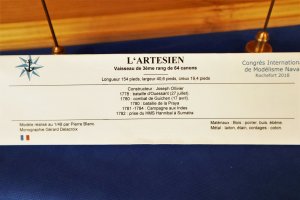

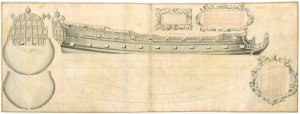

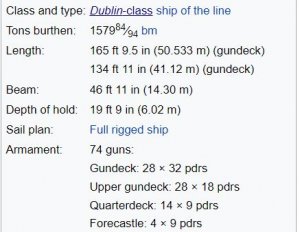

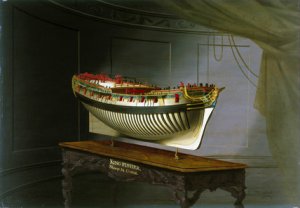

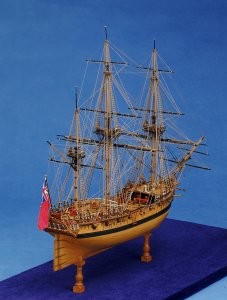

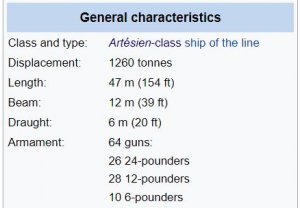

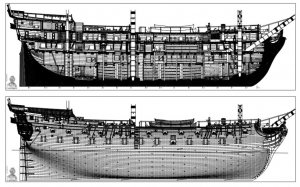

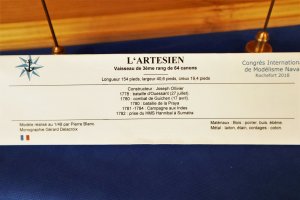

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard detail and figurehead outline, and longitudinal half-breadth with deck details for 'Princessa' (1740), a captured Spanish Third Rate. The plan shows modifications done to fit her as a 74-gun Third Rate, two decker

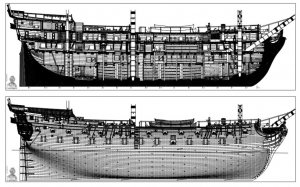

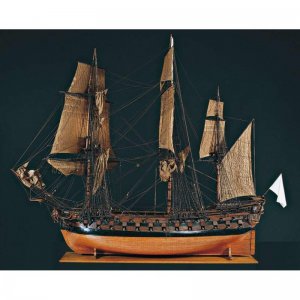

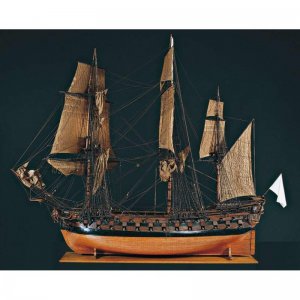

Scale: 1:48. A block design model of the ‘Princessa’ (1730), a Spanish 70-gun, two-decker, third-rate ship of the line. The model is made to moulded beam. The name ‘Princessa’ is marked on the starboard broadside. The ship was built in Santander in 1730. Its dimensions were 165 feet by 50 feet, and it weighed approximately 1714 tons burden. Its complement was 630 men. It carried twenty-eight 32-pound guns on its gun deck, twenty-eight 18-pounders on its upper deck, ten 9-pounders on its quarterdeck and four 9-pounders on its forecastle. It was a powerful vessel and was highly prized by the Royal Navy when it was taken in 1740, albeit requiring the combined force of three British 70-gunners (including the ‘Kent’ SLR0421) to do so. The ‘Princessa’ was larger and heavier than British 70-gunners of the period, and it was important in the navy’s development of the larger 74-gun third rates that replaced the ‘70s’ from the 1740s. In British service, the ‘Princessa’ was stationed in the Mediterranean from 1743 to 1746 and took part in the Battle of Toulon in February 1744. It then spent two years on the Leewards Islands station, then two at Louisbourg, before returning to the Mediterranean in 1747–48. The ‘Princessa’ was hulked at Portsmouth in 1761, and sold in 1784

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/80957.html

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-340760;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=P

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org