Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

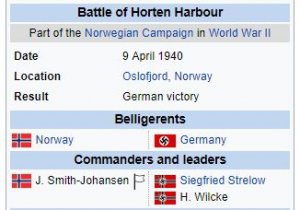

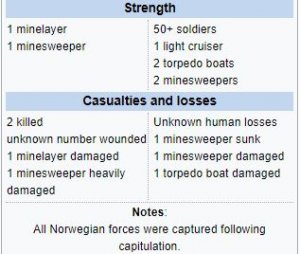

9 April 1940 - The Battle of Drøbak Sound took place in Drøbak Sound, the northernmost part of the outer Oslofjord in southern Norway.

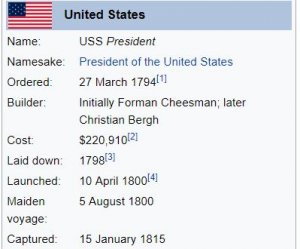

German cruiser Blücher was sunk by Norwegian shore defences, killing 830 of 2,202 troops and crew aboard.

Part II - The Blücher

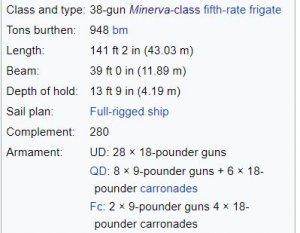

Blücher was the second of five Admiral Hipper-class heavy cruisers of Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine (War Navy), built after the rise of the Nazi Party and the repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles. Named for Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, the Prussian victor of the Battle of Waterloo, the ship was laid down in August 1936 and launched in June 1937. She was completed in September 1939, shortly after the outbreak of World War II. After completing a series of sea trials and training exercises, the ship was pronounced ready for service with the fleet on 5 April 1940. She was armed with a main battery of eight 20.3 cm (8.0 in) guns and, although nominally under the 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) limit set by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, actually displaced over 16,000 long tons (16,000 t).

Immediately upon entering service, Blücher was assigned to the task force that supported the invasion of Norway in April 1940. Blücher served as the flagship of Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Oskar Kummetz, the commander of Group 5. The ship led the flotilla of warships into the Oslofjord on the night of 8 April, to seize Oslo, the capital of Norway. Two old 28 cm (11 in) coastal guns in the Oscarsborg Fortress engaged the ship at very close range, scoring two hits, as did several smaller guns in other batteries. Two torpedoes fired by land-based torpedo batteries struck the ship, causing serious damage. A major fire broke out aboard Blücher, which could not be contained. The fire spread to one of her anti-aircraft gun magazines, causing a large explosion, and then spread further to the ship's fuel bunkers. Blücher then capsized and sank with major loss of life.

The wreck lies at the bottom of Oslofjord, and in 2016 was designated as a war memorial to protect it from looters. Several artifacts have been raised from the wreck, including one of her Arado 196 floatplanes, which was recovered during an operation to pump out leaking fuel oil from the ship in 1994.

Design

Main article: Admiral Hipper-class cruiser

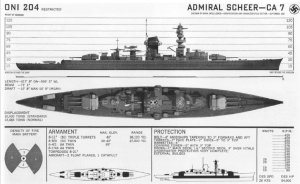

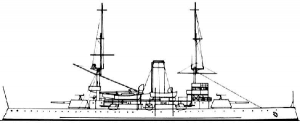

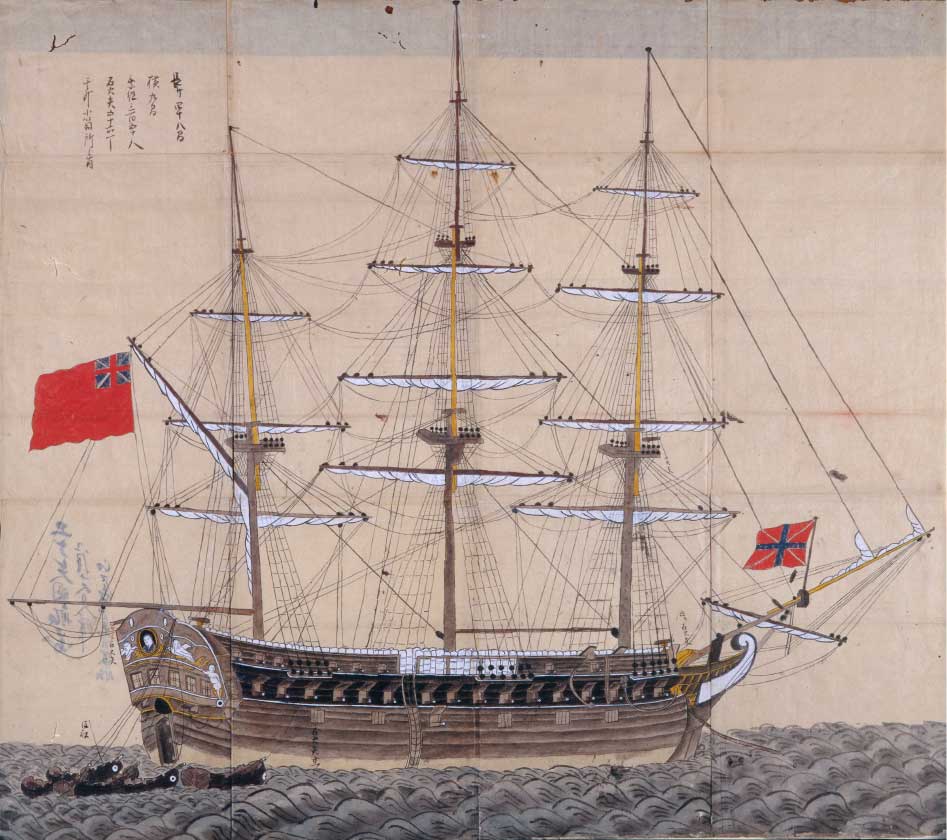

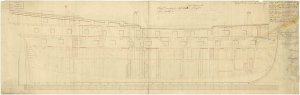

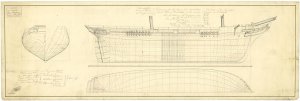

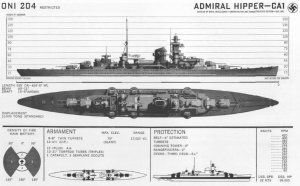

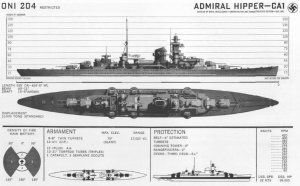

Recognition drawing of an Admiral Hipper-class cruiser

The Admiral Hipper class of heavy cruisers was ordered in the context of German naval rearmament after the Nazi Party came to power in 1933 and repudiated the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. In 1935, Germany signed the Anglo–German Naval Agreement with Great Britain, which provided a legal basis for German naval rearmament; the treaty specified that Germany would be able to build five 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) "treaty cruisers". The Admiral Hippers were nominally within the 10,000-ton limit, though they significantly exceeded the figure.

As launched, Blücher was 202.80 meters (665.4 ft) long overall, had a beam of 21.30 m (69.9 ft) and a maximum draft of 7.74 m (25.4 ft). The ship had a design displacement of 16,170 t (15,910 long tons; 17,820 short tons) and a full load displacement of 18,200 long tons (18,500 t). Blücher was powered by three sets of Blohm & Voss geared steam turbines that drove three propellers. The turbines were supplied with steam by twelve ultra-high pressure oil-fired boilers. The ship's top speed was 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) at 132,000 shaft horsepower (98,000 kW). As designed, her standard complement consisted of 42 officers and 1,340 enlisted men.

Blücher's primary armament was eight 20.3 cm (8.0 in) SK L/60 guns mounted in four twin gun turrets, placed in superfiring pairs forward and aft. Her anti-aircraft battery consisted of twelve 10.5 cm (4.1 in) L/65 guns, twelve 3.7 cm (1.5 in) guns, and eight 2 cm (0.79 in) guns. She had four triple 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo launchers, all on the main deck next to the four range finders for the anti-aircraft guns.

Blücher's armored belt was 70 to 80 mm (2.8 to 3.1 in) thick; her upper deck was 12 to 30 mm (0.47 to 1.18 in) thick while the main armored deck was 20 to 50 mm (0.79 to 1.97 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 105 mm (4.1 in) thick faces and 70 mm thick sides. The ship was equipped with three Arado Ar 196 seaplanes and one catapult. Blucher never had more than two seaplanes on board, and en route to Oslo one had to rest on the catapult as one of the hangars was used for storing bombs and torpedoes.

Service history

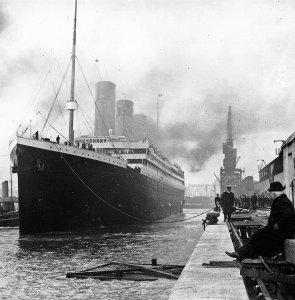

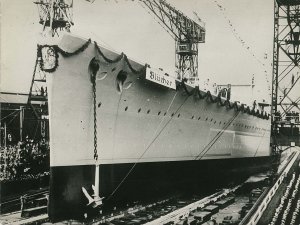

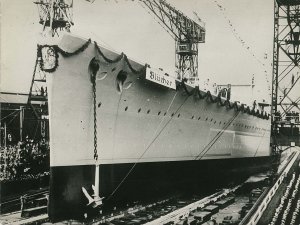

Blücher launching at Kiel, 8 June 1937

Blücher was ordered by the Kriegsmarine from the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel. Her keel was laid on 15 August 1936, under construction number 246. The ship was launched on 8 June 1937, and was completed slightly over two years later, on 20 September 1939, the day she was commissioned into the German fleet. The commanding admiral of the Marinestation der Ostsee (Baltic Naval Station), Admiral Conrad Albrecht, gave the christening speech. Mrs. Erdmann, widow of Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Captain) Alexander Erdmann, former commander of SMS Blücher who had died in the ship's sinking, performed the christening. As built, the ship had a straight stem, though after her launch this was replaced with a clipper bow increasing the overall length to 205.90 meters (675.5 ft). A raked funnel cap was also installed.

Blücher spent most of November 1939 fitting out and finishing additional improvements. By the end of the month, the ship was ready for sea trials; she steamed to Gotenhafen in the Baltic Sea. The trials lasted until mid-December, after which the ship returned to Kiel for final modifications. In January 1940, she resumed her exercises in the Baltic, but by the middle of the month, severe ice forced the ship to remain in port. On 5 April, she was deemed to be ready for action, and was therefore assigned to the forces participating in the invasion of Norway.

Operation Weserübung

Main article: Operation Weserübung

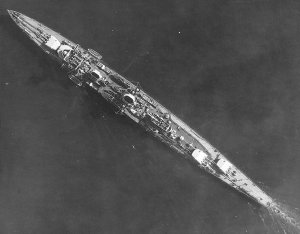

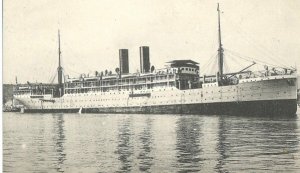

Blücher en route to Norway, as seen from the light cruiser Emden

On 5 April 1940, Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Oskar Kummetz came aboard the ship while she was in Swinemünde. An 800-strong detachment of ground troops from the 163rd Infantry Division also boarded. Three days later, on 8 April, Blücher left port, bound for Norway; she was the flagship for the force that was to seize Oslo, the Norwegian capital, Group 5 of the invasion force, She was accompanied by the heavy cruiser Lützow, the light cruiser Emden, and several smaller escorts. The British submarine Triton spotted the convoy steaming through the Kattegat and Skagerrak, and fired a spread of torpedoes; the Germans evaded the torpedoes, however, and proceeded with the mission.

Night had fallen by the time the German flotilla reached the approaches to the Oslofjord. Shortly after 23:00 (Norwegian time), the Norwegian patrol boat Pol III spotted the flotilla. The German torpedo boat Albatros attacked Pol IIIand set her on fire, but not before the Norwegian patrol boat raised the alarm with a radio report of being attacked by unknown warships. At 23:30 (Norwegian time) the south battery on Rauøy spotted the flotilla in the searchlight and fired two warning shots. Five minutes later, the guns at the Rauøy battery fired four rounds at the approaching Germans, but visibility was poor and no hits were scored. The guns at Bolærne fired only one warning shot at 23:32. Before Blücher could be targeted again, she was out of the firing sector of these shore guns and was seen no more by them after 23:35.

The German flotilla steamed on at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Shortly after midnight (Norwegian time), an order from the Commanding Admiral to extinguish all lighthouses and navigation lights was broadcast over the NRK (Norsk rikskringkasting) [Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation]. The German ships had been ordered to fire only in the event they were directly fired on first. Between 00:30 and 02:00, the flotilla stopped and 150 infantrymen of the landing force were transferred to the escorts R17 and R21 (from Emden) and R18 and R19 (from Blücher).

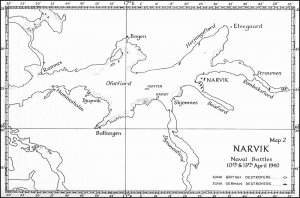

Battle of Drøbak Sound

Main article: Battle of Drøbak Sound

One of the three 28 cm (11 in) guns at Oscarsborg Fortress

The R-boats were ordered to engage Rauøy, Bolærne and the naval port and city of Horten. Despite the apparent loss of surprise, the Blücher proceeded further into the fjord to continue with the timetable to reach Oslo by dawn. At 04:20, Norwegian searchlights again illuminated the ship and at 04:21 the 28 cm (11 in) guns of Oscarsborg Fortress opened fire on Blücher at very close range, beginning the Battle of Drøbak Sound with two hits on her port side. The first was high above the bridge, hitting the battle station for the commander of the anti-aircraft guns. The main range finder in the top of the battle mast was knocked out of alignment, but Blücher had four more major rangefinders. The second 28 cm shell struck near the aircraft hangar and started a major fire. As the fire spread, it detonated explosives carried for the infantry, hindering firefighting efforts. The explosion set fire to the two Arado seaplanes on board: one on the catapult and the other in one of the hangars. The explosion also probably punched a hole in the armored deck over turbine room 1. Turbine 1 and generator room 3 stopped for lack of steam and only the outboard shafts from turbine room 2/3 were operational.

The Germans were unable to locate the source of the gunfire. Blücher increased speed to 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) in an attempt to get past the Norwegian guns. The 15 cm (5.9 in) guns on Drøbak, some 400 yd (370 m) on Blücher's starboard side, opened fire as well. At a distance of 500 m (1,600 ft) Blücher entered the narrows between Kopås and Hovedbatteriet, the main battery, at Kaholmen. The Kopås battery ceased firing at Blücher and engaged the next target, Lützow, scoring multiple hits. First engineer Karl Thannemann wrote in his report that the hits from the guns on Drøbak, which were fired on the starboard side, were all between section IV and X in a length of 75 m (246 ft) amidships, between B-turret and C-turret. However, all damage was on the port side. After the first salvo from the 15 cm batteries in Drøbak, the steering from the bridge was disabled. Blücher had just passed Drøbakgrunnen (Drøbak shallows) and was in a turn to port. The commander got her back on track by using the side shafts, but she lost speed. At 04:34 Norwegian land-based torpedo batteries scored two hits on the ship.

Blücher on fire and sinking in Drøbak Sound

According to Kummetz's report, the first torpedo hit Boiler Room 2, just under the funnel, and the second hit Turbine Room 2/3 (the turbine room for the side shafts). Boiler 1 had already been destroyed by gunfire. Only one boiler remained, but the steam pipes through Boilers 1 and 2 and Turbine Room 2/3 had been damaged and Turbine 1 had lost power. By 04:34, the ship had been severely damaged, but had successfully passed through the firing zone; most the Norwegian guns could no longer bear on her. The 15 cm guns in the Kopås battery were all standing in open positions with a wide sector of firing, and they were still within range. The battery crews asked for orders, but the commander of the fortress, Birger Eriksen, concluded: "The fortress has served its purpose".

After passing the gun batteries, the crew, including the personnel manning the guns, were tasked with fighting the fire. By that time she had taken on a list of 18 degrees, although this was not initially problematic. The fire eventually reached one of the ship's 10.5 cm ammunition magazines between turbine room 1 and turbine room 2/3, which exploded violently. The blast ruptured several bulkheads in the engine rooms and ignited the ship's fuel stores. The battered ship slowly began to capsize and the order to abandon ship was given. Blücher rolled over and sank at 07:30, with significant casualties. Naval historian Erich Gröner states that the number of casualties is unknown, and Henrik Lunde gives a loss of life figure ranging between 600 and 1,000 soldiers and sailors. Jürgen Rohwer meanwhile states that 125 seamen and 195 soldiers died in the sinking.

The loss of Blücher and the damage done to Lützow caused the German force to withdraw. The ground troops were landed on the eastern side of the fjord; they proceeded inland and captured the Oscarborg Fortress by 09:00 on 10 April. They then moved on to attack the capital. Airborne troops captured the Fornebu Airport and completed the encirclement of the city, and by 14:00 on 10 April it was in German hands. The delay caused by the temporary withdrawal of Blücher's task force, however, allowed the Norwegian government and royal family to escape the city.

Wreck

One of Blücher's anchors is now at Aker Brygge in Oslo

Blücher remains at the bottom of the Drøbak Narrows, at a depth of 35 fathoms (210 ft; 64 m). The ship's screws were removed in 1953, and there have been several proposals to raise the wreck since 1963, but none have been carried out. When Blücher left Germany, she had about 2,670 cubic meters (94,000 cu ft) of oil on board. She expended some of the fuel en route to Norway, and some was lost in the sinking, but she was constantly leaking oil. In 1991 the leakage rate increased to 50 liters (11 imp gal; 13 U.S. gal) per day, threatening the environment. The Norwegian government therefore decided to remove as much oil as possible from the wreck. In October 1994 the company Rockwater AS, together with deep sea divers, drilled holes in 133 fuel tanks and removed 1,000 t (980 long tons; 1,100 short tons) of oil; 47 fuel bunkers were unreachable and may still contain oil. After being run through a cleaning process, the oil was sold. The oil extraction operation provided an opportunity to recover one of Blücher's two Arado 196 aircraft. The plane was raised on 9 November 1994 and is currently at the Flyhistorisk Museum, Sola aviation museum near Stavanger.

The shipwreck was protected as a war memorial on 16 June 2016, but also protected by law by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage for those who actually have their burial at the bottom of the fjord. The intention was to protect the ship from looters

The Admiral Hipper class was a group of five heavy cruisers built by Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine beginning in the mid-1930s. The class comprised Admiral Hipper, the lead ship, Blücher, Prinz Eugen, Seydlitz, and Lützow. Only the first three ships of the class saw action with the German Navy during World War II. Work on Seydlitz stopped when she was approximately 95 percent complete; it was decided to convert her into an aircraft carrier, but this was not completed either. Lützow was sold incomplete to the Soviet Union in 1940.

Admiral Hipper and Blücher took part in Operation Weserübung, the invasion of Norway in April 1940. Blücher was sunk by Norwegian coastal defenses outside Oslo while Admiral Hipper led the attack on Trondheim. She then conducted sorties into the Atlantic to attack Allied merchant shipping. In 1942, she was deployed to northern Norway to attack shipping to the Soviet Union, culminating in the Battle of the Barents Sea in December 1942, where she was damaged by British cruisers. Prinz Eugen saw her first action during Operation Rheinübung with the battleship Bismarck. She eventually returned to Germany during the Channel Dash in 1942, after which she too went to Norway. After being torpedoed by a British submarine, she returned to Germany for repairs. Admiral Hipper while decommissioned after returning to Germany in early 1943, was partially repaired and recommissioned in the fall of 1944 for a refugee transport mission in 1945. Only Prinz Eugen continued to serve in full commission and stayed in the Baltic until the end of the war.

Admiral Hipper was scuttled in Kiel in May 1945, leaving Prinz Eugen as the only member of the class to survive the war. She was ceded to the US Navy, which ultimately expended the ship in the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests in 1946. Seydlitz was towed to Königsberg and scuttled before the advancing Soviet Army could seize the ship. She was ultimately raised and broken up for scrap. Lützow, renamed Petropavlovsk, remained unfinished when the Germans invaded the Soviet Union. The ship provided artillery support against advancing German forces until she was sunk in September 1941. She was raised a year later and repaired enough to participate in the campaign to relieve the Siege of Leningrad in 1944. She served on in secondary roles until the 1950s, when she was broken up.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_cruiser_Blücher

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admiral_Hipper-class_cruiser

9 April 1940 - The Battle of Drøbak Sound took place in Drøbak Sound, the northernmost part of the outer Oslofjord in southern Norway.

German cruiser Blücher was sunk by Norwegian shore defences, killing 830 of 2,202 troops and crew aboard.

Part II - The Blücher

Blücher was the second of five Admiral Hipper-class heavy cruisers of Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine (War Navy), built after the rise of the Nazi Party and the repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles. Named for Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, the Prussian victor of the Battle of Waterloo, the ship was laid down in August 1936 and launched in June 1937. She was completed in September 1939, shortly after the outbreak of World War II. After completing a series of sea trials and training exercises, the ship was pronounced ready for service with the fleet on 5 April 1940. She was armed with a main battery of eight 20.3 cm (8.0 in) guns and, although nominally under the 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) limit set by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, actually displaced over 16,000 long tons (16,000 t).

Immediately upon entering service, Blücher was assigned to the task force that supported the invasion of Norway in April 1940. Blücher served as the flagship of Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Oskar Kummetz, the commander of Group 5. The ship led the flotilla of warships into the Oslofjord on the night of 8 April, to seize Oslo, the capital of Norway. Two old 28 cm (11 in) coastal guns in the Oscarsborg Fortress engaged the ship at very close range, scoring two hits, as did several smaller guns in other batteries. Two torpedoes fired by land-based torpedo batteries struck the ship, causing serious damage. A major fire broke out aboard Blücher, which could not be contained. The fire spread to one of her anti-aircraft gun magazines, causing a large explosion, and then spread further to the ship's fuel bunkers. Blücher then capsized and sank with major loss of life.

The wreck lies at the bottom of Oslofjord, and in 2016 was designated as a war memorial to protect it from looters. Several artifacts have been raised from the wreck, including one of her Arado 196 floatplanes, which was recovered during an operation to pump out leaking fuel oil from the ship in 1994.

Design

Main article: Admiral Hipper-class cruiser

Recognition drawing of an Admiral Hipper-class cruiser

The Admiral Hipper class of heavy cruisers was ordered in the context of German naval rearmament after the Nazi Party came to power in 1933 and repudiated the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. In 1935, Germany signed the Anglo–German Naval Agreement with Great Britain, which provided a legal basis for German naval rearmament; the treaty specified that Germany would be able to build five 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) "treaty cruisers". The Admiral Hippers were nominally within the 10,000-ton limit, though they significantly exceeded the figure.

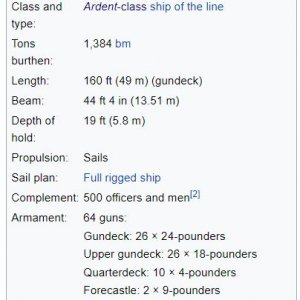

As launched, Blücher was 202.80 meters (665.4 ft) long overall, had a beam of 21.30 m (69.9 ft) and a maximum draft of 7.74 m (25.4 ft). The ship had a design displacement of 16,170 t (15,910 long tons; 17,820 short tons) and a full load displacement of 18,200 long tons (18,500 t). Blücher was powered by three sets of Blohm & Voss geared steam turbines that drove three propellers. The turbines were supplied with steam by twelve ultra-high pressure oil-fired boilers. The ship's top speed was 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) at 132,000 shaft horsepower (98,000 kW). As designed, her standard complement consisted of 42 officers and 1,340 enlisted men.

Blücher's primary armament was eight 20.3 cm (8.0 in) SK L/60 guns mounted in four twin gun turrets, placed in superfiring pairs forward and aft. Her anti-aircraft battery consisted of twelve 10.5 cm (4.1 in) L/65 guns, twelve 3.7 cm (1.5 in) guns, and eight 2 cm (0.79 in) guns. She had four triple 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo launchers, all on the main deck next to the four range finders for the anti-aircraft guns.

Blücher's armored belt was 70 to 80 mm (2.8 to 3.1 in) thick; her upper deck was 12 to 30 mm (0.47 to 1.18 in) thick while the main armored deck was 20 to 50 mm (0.79 to 1.97 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 105 mm (4.1 in) thick faces and 70 mm thick sides. The ship was equipped with three Arado Ar 196 seaplanes and one catapult. Blucher never had more than two seaplanes on board, and en route to Oslo one had to rest on the catapult as one of the hangars was used for storing bombs and torpedoes.

Service history

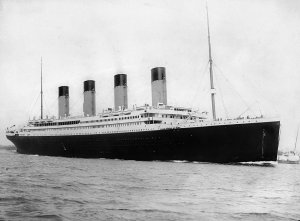

Blücher launching at Kiel, 8 June 1937

Blücher was ordered by the Kriegsmarine from the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel. Her keel was laid on 15 August 1936, under construction number 246. The ship was launched on 8 June 1937, and was completed slightly over two years later, on 20 September 1939, the day she was commissioned into the German fleet. The commanding admiral of the Marinestation der Ostsee (Baltic Naval Station), Admiral Conrad Albrecht, gave the christening speech. Mrs. Erdmann, widow of Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Captain) Alexander Erdmann, former commander of SMS Blücher who had died in the ship's sinking, performed the christening. As built, the ship had a straight stem, though after her launch this was replaced with a clipper bow increasing the overall length to 205.90 meters (675.5 ft). A raked funnel cap was also installed.

Blücher spent most of November 1939 fitting out and finishing additional improvements. By the end of the month, the ship was ready for sea trials; she steamed to Gotenhafen in the Baltic Sea. The trials lasted until mid-December, after which the ship returned to Kiel for final modifications. In January 1940, she resumed her exercises in the Baltic, but by the middle of the month, severe ice forced the ship to remain in port. On 5 April, she was deemed to be ready for action, and was therefore assigned to the forces participating in the invasion of Norway.

Operation Weserübung

Main article: Operation Weserübung

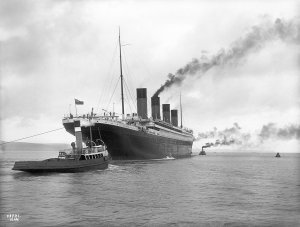

Blücher en route to Norway, as seen from the light cruiser Emden

On 5 April 1940, Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Oskar Kummetz came aboard the ship while she was in Swinemünde. An 800-strong detachment of ground troops from the 163rd Infantry Division also boarded. Three days later, on 8 April, Blücher left port, bound for Norway; she was the flagship for the force that was to seize Oslo, the Norwegian capital, Group 5 of the invasion force, She was accompanied by the heavy cruiser Lützow, the light cruiser Emden, and several smaller escorts. The British submarine Triton spotted the convoy steaming through the Kattegat and Skagerrak, and fired a spread of torpedoes; the Germans evaded the torpedoes, however, and proceeded with the mission.

Night had fallen by the time the German flotilla reached the approaches to the Oslofjord. Shortly after 23:00 (Norwegian time), the Norwegian patrol boat Pol III spotted the flotilla. The German torpedo boat Albatros attacked Pol IIIand set her on fire, but not before the Norwegian patrol boat raised the alarm with a radio report of being attacked by unknown warships. At 23:30 (Norwegian time) the south battery on Rauøy spotted the flotilla in the searchlight and fired two warning shots. Five minutes later, the guns at the Rauøy battery fired four rounds at the approaching Germans, but visibility was poor and no hits were scored. The guns at Bolærne fired only one warning shot at 23:32. Before Blücher could be targeted again, she was out of the firing sector of these shore guns and was seen no more by them after 23:35.

The German flotilla steamed on at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Shortly after midnight (Norwegian time), an order from the Commanding Admiral to extinguish all lighthouses and navigation lights was broadcast over the NRK (Norsk rikskringkasting) [Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation]. The German ships had been ordered to fire only in the event they were directly fired on first. Between 00:30 and 02:00, the flotilla stopped and 150 infantrymen of the landing force were transferred to the escorts R17 and R21 (from Emden) and R18 and R19 (from Blücher).

Battle of Drøbak Sound

Main article: Battle of Drøbak Sound

One of the three 28 cm (11 in) guns at Oscarsborg Fortress

The R-boats were ordered to engage Rauøy, Bolærne and the naval port and city of Horten. Despite the apparent loss of surprise, the Blücher proceeded further into the fjord to continue with the timetable to reach Oslo by dawn. At 04:20, Norwegian searchlights again illuminated the ship and at 04:21 the 28 cm (11 in) guns of Oscarsborg Fortress opened fire on Blücher at very close range, beginning the Battle of Drøbak Sound with two hits on her port side. The first was high above the bridge, hitting the battle station for the commander of the anti-aircraft guns. The main range finder in the top of the battle mast was knocked out of alignment, but Blücher had four more major rangefinders. The second 28 cm shell struck near the aircraft hangar and started a major fire. As the fire spread, it detonated explosives carried for the infantry, hindering firefighting efforts. The explosion set fire to the two Arado seaplanes on board: one on the catapult and the other in one of the hangars. The explosion also probably punched a hole in the armored deck over turbine room 1. Turbine 1 and generator room 3 stopped for lack of steam and only the outboard shafts from turbine room 2/3 were operational.

The Germans were unable to locate the source of the gunfire. Blücher increased speed to 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) in an attempt to get past the Norwegian guns. The 15 cm (5.9 in) guns on Drøbak, some 400 yd (370 m) on Blücher's starboard side, opened fire as well. At a distance of 500 m (1,600 ft) Blücher entered the narrows between Kopås and Hovedbatteriet, the main battery, at Kaholmen. The Kopås battery ceased firing at Blücher and engaged the next target, Lützow, scoring multiple hits. First engineer Karl Thannemann wrote in his report that the hits from the guns on Drøbak, which were fired on the starboard side, were all between section IV and X in a length of 75 m (246 ft) amidships, between B-turret and C-turret. However, all damage was on the port side. After the first salvo from the 15 cm batteries in Drøbak, the steering from the bridge was disabled. Blücher had just passed Drøbakgrunnen (Drøbak shallows) and was in a turn to port. The commander got her back on track by using the side shafts, but she lost speed. At 04:34 Norwegian land-based torpedo batteries scored two hits on the ship.

Blücher on fire and sinking in Drøbak Sound

According to Kummetz's report, the first torpedo hit Boiler Room 2, just under the funnel, and the second hit Turbine Room 2/3 (the turbine room for the side shafts). Boiler 1 had already been destroyed by gunfire. Only one boiler remained, but the steam pipes through Boilers 1 and 2 and Turbine Room 2/3 had been damaged and Turbine 1 had lost power. By 04:34, the ship had been severely damaged, but had successfully passed through the firing zone; most the Norwegian guns could no longer bear on her. The 15 cm guns in the Kopås battery were all standing in open positions with a wide sector of firing, and they were still within range. The battery crews asked for orders, but the commander of the fortress, Birger Eriksen, concluded: "The fortress has served its purpose".

After passing the gun batteries, the crew, including the personnel manning the guns, were tasked with fighting the fire. By that time she had taken on a list of 18 degrees, although this was not initially problematic. The fire eventually reached one of the ship's 10.5 cm ammunition magazines between turbine room 1 and turbine room 2/3, which exploded violently. The blast ruptured several bulkheads in the engine rooms and ignited the ship's fuel stores. The battered ship slowly began to capsize and the order to abandon ship was given. Blücher rolled over and sank at 07:30, with significant casualties. Naval historian Erich Gröner states that the number of casualties is unknown, and Henrik Lunde gives a loss of life figure ranging between 600 and 1,000 soldiers and sailors. Jürgen Rohwer meanwhile states that 125 seamen and 195 soldiers died in the sinking.

The loss of Blücher and the damage done to Lützow caused the German force to withdraw. The ground troops were landed on the eastern side of the fjord; they proceeded inland and captured the Oscarborg Fortress by 09:00 on 10 April. They then moved on to attack the capital. Airborne troops captured the Fornebu Airport and completed the encirclement of the city, and by 14:00 on 10 April it was in German hands. The delay caused by the temporary withdrawal of Blücher's task force, however, allowed the Norwegian government and royal family to escape the city.

Wreck

One of Blücher's anchors is now at Aker Brygge in Oslo

Blücher remains at the bottom of the Drøbak Narrows, at a depth of 35 fathoms (210 ft; 64 m). The ship's screws were removed in 1953, and there have been several proposals to raise the wreck since 1963, but none have been carried out. When Blücher left Germany, she had about 2,670 cubic meters (94,000 cu ft) of oil on board. She expended some of the fuel en route to Norway, and some was lost in the sinking, but she was constantly leaking oil. In 1991 the leakage rate increased to 50 liters (11 imp gal; 13 U.S. gal) per day, threatening the environment. The Norwegian government therefore decided to remove as much oil as possible from the wreck. In October 1994 the company Rockwater AS, together with deep sea divers, drilled holes in 133 fuel tanks and removed 1,000 t (980 long tons; 1,100 short tons) of oil; 47 fuel bunkers were unreachable and may still contain oil. After being run through a cleaning process, the oil was sold. The oil extraction operation provided an opportunity to recover one of Blücher's two Arado 196 aircraft. The plane was raised on 9 November 1994 and is currently at the Flyhistorisk Museum, Sola aviation museum near Stavanger.

The shipwreck was protected as a war memorial on 16 June 2016, but also protected by law by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage for those who actually have their burial at the bottom of the fjord. The intention was to protect the ship from looters

The Admiral Hipper class was a group of five heavy cruisers built by Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine beginning in the mid-1930s. The class comprised Admiral Hipper, the lead ship, Blücher, Prinz Eugen, Seydlitz, and Lützow. Only the first three ships of the class saw action with the German Navy during World War II. Work on Seydlitz stopped when she was approximately 95 percent complete; it was decided to convert her into an aircraft carrier, but this was not completed either. Lützow was sold incomplete to the Soviet Union in 1940.

Admiral Hipper and Blücher took part in Operation Weserübung, the invasion of Norway in April 1940. Blücher was sunk by Norwegian coastal defenses outside Oslo while Admiral Hipper led the attack on Trondheim. She then conducted sorties into the Atlantic to attack Allied merchant shipping. In 1942, she was deployed to northern Norway to attack shipping to the Soviet Union, culminating in the Battle of the Barents Sea in December 1942, where she was damaged by British cruisers. Prinz Eugen saw her first action during Operation Rheinübung with the battleship Bismarck. She eventually returned to Germany during the Channel Dash in 1942, after which she too went to Norway. After being torpedoed by a British submarine, she returned to Germany for repairs. Admiral Hipper while decommissioned after returning to Germany in early 1943, was partially repaired and recommissioned in the fall of 1944 for a refugee transport mission in 1945. Only Prinz Eugen continued to serve in full commission and stayed in the Baltic until the end of the war.

Admiral Hipper was scuttled in Kiel in May 1945, leaving Prinz Eugen as the only member of the class to survive the war. She was ceded to the US Navy, which ultimately expended the ship in the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests in 1946. Seydlitz was towed to Königsberg and scuttled before the advancing Soviet Army could seize the ship. She was ultimately raised and broken up for scrap. Lützow, renamed Petropavlovsk, remained unfinished when the Germans invaded the Soviet Union. The ship provided artillery support against advancing German forces until she was sunk in September 1941. She was raised a year later and repaired enough to participate in the campaign to relieve the Siege of Leningrad in 1944. She served on in secondary roles until the 1950s, when she was broken up.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_cruiser_Blücher

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admiral_Hipper-class_cruiser