Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

4 May 1945 - USS Morrison – On 4 May 1945, in the Battle of Okinawa, the US destroyer was sunk after being hit by four kamikaze aircraft.

After the fourth hit the destroyer, heavily damaged, began to list sharply to starboard. Two explosions occurred almost simultaneously that lifted her bow in the air. She then sank so quickly that most men below decks were killed. 152 men were killed.

USS Morrison (DD-560), a Fletcher-class destroyer, was a ship of the United States Navy, named for Coxswain John G. Morrison (1838–1897), who received the Medal of Honor for exceptional bravery during the Civil War.

Morrison was laid down by Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corp., Seattle, Wash., 30 June 1942; launched 4 July 1943, sponsored by Miss Margaret M. Morrison, daughter of Coxswain Morrison; and commissioned 18 December 1943, Commander Walter H. Price in command.

After shakedown off San Diego, California, Morrison departed Seattle 25 February 1944 for the South Pacific, via Pearl Harbor and the Marshalls. In mid-April the destroyer joined TG 50.17 for screening operations off Seeadler Harbor, Manus, Admiralties, during the fueling of carriers then striking Japanese installations in the Carolines.

USS Morrison (DD-560), viewed from Gambier Bay(CVE-73), 24 July 1944.

Battle of Okinawa

After shore bombardment exercises in the Hawaiian Islands, Morrison departed for Ulithi 3 March. By 21 March she had joined TF 54 underway to support the invasion of Okinawa. The destroyer arrived off the southern shores of Okinawa on the 25th, 7 days before the landings 1 April, and joined in the preparations of bombardment.

In the early morning of 31 March she sank Japanese submarine I-8. After Stockton (DD-646) made a positive sound contact off Okinawa and expended her depth charges in the attack, Morrison arrived on the scene to see the submarine surface, then immediately submerge. She dropped a pattern of charges which seconds later forced the sub to the surface where it was sunk by gunfire. At daylight Morrison's small boats rescued the lone survivor.

The ship continued shore bombardment, night illumination, and screen operations off Ōshima Beach. On the night of 11 April Morrison assisted Anthony (DD-515) in illuminating and sinking enemy landing craft heading north along the beach.

Three days later Morrison began radar picket duty. Her first two stations, southwest of Okinawa, were occasionally raided at night. She replaced Daly (DD-519) at the third station 28 April after the other destroyer was hit by a kamikaze.

On 30 April Morrison was shifted to the most critical station on the picket line. After 3 days of bad weather had prevented air raids, the dawn of 4 May was bright, clear, and ominous. At 07:15 the combat air patrol was called on to stop a force of about 25 planes headed toward Morrison, but some got through.

The first attack on Morrison, a main target as fighter-director ship, was a suicide run by a "Zeke". The plane broke through heavy flak to drop a bomb which splashed off the starboard beam and exploded harmlessly. Next a "Val" and another "Zeke" followed with unsuccessful suicide runs. About 08:25 a "Zeke" approached through intense antiaircraft fire to crash into a stack and the bridge. The blow inflicted heavy casualties and knocked out most of the electrical equipment. The next three planes, all old twin-float biplanes, maneuvered, despite heavy attack, to crash into the damaged ship. With the fourth hit, Morrison, heavily damaged, began to list sharply to starboard.

Few communication circuits remained intact enough to transmit the order to abandon ship. Two explosions occurred almost simultaneously, the bow lifted into the air, and by 08:40 Morrison had plunged beneath the surface. The ship sank so quickly that most men below decks were lost, a total of 152.

In July 1957 the sunken hull of Morrison was donated, along with those of some 26 other ships sunk in the Ryukyus area to the Government of the Ryukyu Islands for salvage.

Morrison received eight battle stars for World War II service.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Morrison_(DD-560)

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

4 May 1945 - USS Morrison – On 4 May 1945, in the Battle of Okinawa, the US destroyer was sunk after being hit by four kamikaze aircraft.

After the fourth hit the destroyer, heavily damaged, began to list sharply to starboard. Two explosions occurred almost simultaneously that lifted her bow in the air. She then sank so quickly that most men below decks were killed. 152 men were killed.

USS Morrison (DD-560), a Fletcher-class destroyer, was a ship of the United States Navy, named for Coxswain John G. Morrison (1838–1897), who received the Medal of Honor for exceptional bravery during the Civil War.

Morrison was laid down by Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corp., Seattle, Wash., 30 June 1942; launched 4 July 1943, sponsored by Miss Margaret M. Morrison, daughter of Coxswain Morrison; and commissioned 18 December 1943, Commander Walter H. Price in command.

After shakedown off San Diego, California, Morrison departed Seattle 25 February 1944 for the South Pacific, via Pearl Harbor and the Marshalls. In mid-April the destroyer joined TG 50.17 for screening operations off Seeadler Harbor, Manus, Admiralties, during the fueling of carriers then striking Japanese installations in the Carolines.

USS Morrison (DD-560), viewed from Gambier Bay(CVE-73), 24 July 1944.

Battle of Okinawa

After shore bombardment exercises in the Hawaiian Islands, Morrison departed for Ulithi 3 March. By 21 March she had joined TF 54 underway to support the invasion of Okinawa. The destroyer arrived off the southern shores of Okinawa on the 25th, 7 days before the landings 1 April, and joined in the preparations of bombardment.

In the early morning of 31 March she sank Japanese submarine I-8. After Stockton (DD-646) made a positive sound contact off Okinawa and expended her depth charges in the attack, Morrison arrived on the scene to see the submarine surface, then immediately submerge. She dropped a pattern of charges which seconds later forced the sub to the surface where it was sunk by gunfire. At daylight Morrison's small boats rescued the lone survivor.

The ship continued shore bombardment, night illumination, and screen operations off Ōshima Beach. On the night of 11 April Morrison assisted Anthony (DD-515) in illuminating and sinking enemy landing craft heading north along the beach.

Three days later Morrison began radar picket duty. Her first two stations, southwest of Okinawa, were occasionally raided at night. She replaced Daly (DD-519) at the third station 28 April after the other destroyer was hit by a kamikaze.

On 30 April Morrison was shifted to the most critical station on the picket line. After 3 days of bad weather had prevented air raids, the dawn of 4 May was bright, clear, and ominous. At 07:15 the combat air patrol was called on to stop a force of about 25 planes headed toward Morrison, but some got through.

The first attack on Morrison, a main target as fighter-director ship, was a suicide run by a "Zeke". The plane broke through heavy flak to drop a bomb which splashed off the starboard beam and exploded harmlessly. Next a "Val" and another "Zeke" followed with unsuccessful suicide runs. About 08:25 a "Zeke" approached through intense antiaircraft fire to crash into a stack and the bridge. The blow inflicted heavy casualties and knocked out most of the electrical equipment. The next three planes, all old twin-float biplanes, maneuvered, despite heavy attack, to crash into the damaged ship. With the fourth hit, Morrison, heavily damaged, began to list sharply to starboard.

Few communication circuits remained intact enough to transmit the order to abandon ship. Two explosions occurred almost simultaneously, the bow lifted into the air, and by 08:40 Morrison had plunged beneath the surface. The ship sank so quickly that most men below decks were lost, a total of 152.

In July 1957 the sunken hull of Morrison was donated, along with those of some 26 other ships sunk in the Ryukyus area to the Government of the Ryukyu Islands for salvage.

Morrison received eight battle stars for World War II service.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Morrison_(DD-560)

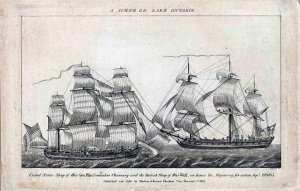

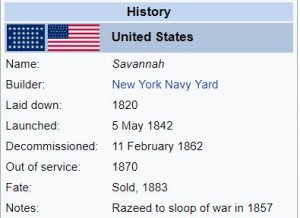

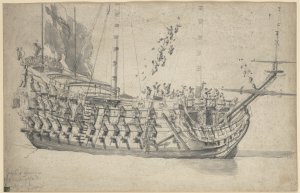

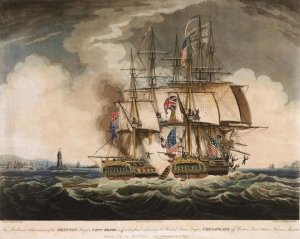

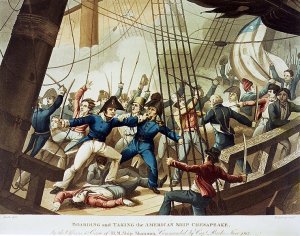

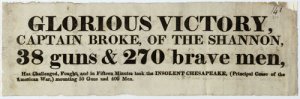

paper announcing the Shannon's victory

paper announcing the Shannon's victory