Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

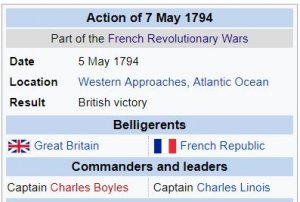

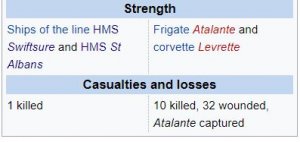

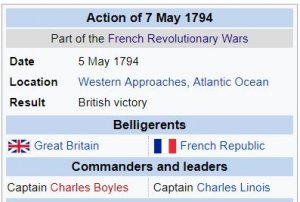

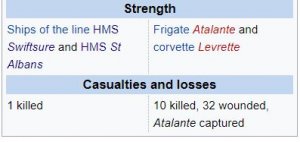

7 May 1794 - The Action of 7 May 1794 was a minor naval action fought between a British ship of the line and a French frigate early in the French Revolutionary Wars.

HMS Swiftsure (74), Captain Charles Boyles, captured Atalante (36), Cptn. Charles-Alexandre-Leon Durand-Linois

The Action of 7 May 1794 was a minor naval action fought between a British ship of the line and a French frigate early in the French Revolutionary Wars. The French Navy sought to disrupt British trade by intercepting and capturing merchant ships with roving frigates, a strategy countered by protecting British convoys with heavier warships, particularly in European waters. On 5 May 1794, the British escorts of a convoy from Cork sighted two French ships approaching and gave chase. The ships, a frigate and a corvette, outmatched by their opponents, separated and the convoy escorts did likewise, each following one of the raiders on a separate course.

By the evening one of the French ships had successfully escaped, but the other was still under pursuit, Captain Charles Linois of Atalante attempting a number of tactics to drive off his opponent but without success. Eventually, after a chase lasting nearly two days, the French ship came within range of the much larger British 74-gun third rate HMS Swiftsure and despite a brave defence was soon forced to surrender after suffering more than 40 casualties. Although he had surrendered his ship, Linois was widely praised for his actions in defending his ship against such heavy odds.

In the aftermath of the engagement, a French battle squadron that formed part of the developing Atlantic campaign of May 1794 pursued both ships for the rest of the day; their quarry eventually escaped after dark. Atalante was later taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Espion.

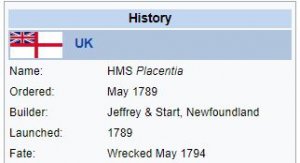

lines NMM, Progress Book, volume 5, folio 543, states that 'Espion' was at Plymouth Dockyard between March and My 1795 being fitted and having defects rectified, and there again in November 1795. She was in Sheerness Dockyard between 1 December 1796 and 16 January 1797 having further defects made good. In 1798 she was fitted as a floating battery and in 1799 as a troopship

Background

The outbreak of war between Britain and France in the spring of 1793 came at a time of differing fortunes for the navies of the two countries. The Royal Navy had been at a state of heightened readiness since 1792 in preparation for the conflict, while the French Navy had still not recovered from the upheavals of the French Revolution, which had resulted in the collapse of the naval hierarchy and a dearth of experienced officers and seamen. French naval strategy early in the war was to send squadrons and light vessels to operate along British trade routes, in order to disrupt British mercantile operations. This resulted in Britain forming its merchant ships into convoys for mutual protection, escorted by warships while in European waters to defend against roving attacks by French ships.

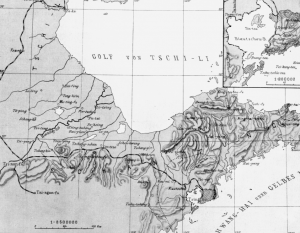

By the spring of 1794, France was in turmoil following the failure of the harvest, which threatened the country with starvation. In order to secure food supplies, France turned to its American colonies and the United States, which assembled a large grain convoy in Hampton Roads. To ensure the security of this convoy, the French Navy dispatched most of its Atlantic Fleet to sea during May 1794, operating in a series of large squadrons, independent cruisers and one major fleet under Villaret de Joyeuse. On 5 May, two French ships operating independently, the 36-gun frigate Atalante under Captain Charles Linois and the corvette Levrette, spied a British convoy sailing south-west, three days out from Cork, and closed to investigate.

Pursuit

The convoy that Linois had sighted was under the protection of two ships of the line, the Swiftsure under Captain Charles Boyles and the 64-gun HMS St Albans under Captain James Vashon. At 17:45, with the French frigates closing from the west and aware that they could not defend the whole convoy without immediate direct action, Boyles turned Swiftsure and St Albans towards the newcomers, hoisting their colours and Swiftsure firing three shots in the direction of the larger ship, Atalante. Together the British ships hugely outweighed and outmatched the French vessels, and as soon as Linois realised his mistake he gave orders for his ships to turn and make all sail to escape pursuit, raising the French tricolour and firing his stern-chasers, guns fitted in the rear of the ship, at his pursuers.

The French ships immediately separated. St Albans then followed Levrette while Swiftsure concentrated on Atalante. Throughout the rest of the evening the two chases continued. Then after darkness fell Levrette was able to outrun and escape from St Albans. Swiftsure however remained in touch with Atalante so that by 04:00 on 6 May the French frigate was approximately 2.5 nautical miles (4.6 km) ahead of the ship of the line to the northwest, with the wind direction to the north-northeast. For the entire following day Linois could not escape Boyles' pursuit, and at 17:30 Swiftsure was close enough to open fire again, using the bow-chasers for an hour and a half until Atalante once more pulled out of range. During the evening the French frigate was able to keep 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) in front of Swiftsure, but at midnight Linois switched his course to the south, hoping that the darkness would cloak the manoeuvre and that Atlante would be able to escape Boyles.

At 02:00 it became clear that Linois's ploy had failed and that Swiftsure was still following Atalante. More importantly, the manoeuvre had severely slowed the frigate. Although Linois hauled closer to the wind, Boyles was able to come within range at 02:30, firing his starboard guns into the smaller ship. Although his crew were exhausted by the extended chase Linois returned fire, the warships exchanging shot at long-range and the frigate suffering far more serious damage during the brief engagement. By 03:25 Linois was forced to surrender, his ship's rigging in tatters and casualties mounting among his crew. Boyles then provided a prize crew to the frigate and took most of the surviving French crew aboard his own ship as prisoners of war. Casualties on the French ship were heavy, with ten killed and 32 wounded from the 274 men aboard, compared to a single man lost on Swiftsure, which had also suffered some damage to its rigging.

Aftermath

Boyles was not long able to enjoy his victory undisturbed: at 10:00 on 7 May, shortly after the removal of the French prisoners had been completed, sails were spotted on the horizon. These were rapidly identified as three French ships of the line that were making all haste to intercept and capture Swiftsure and Atalante. These ships were part of a squadron under Contre-Admiral Joseph-Marie Nielly that had sailed from Rochefort the day before in search of the American grain convoy shortly due in European waters. Issuing rapid orders, Boyles instructed Atalante's prize crew to separate their ship from Swiftsure in order to force the French to split their forces; the frigate and the ship of the line fleeing on different courses. Atalante soon outran pursuit and escaped into the Atlantic, the prize crew even managing to replace the damaged main topsail in the midst of the chase with the assistance of the French prisoners on board. Swiftsure was slower but Boyles was still able to increase the distance between his vessel and the French during the day, finally losing sight of his pursuers at 22:00.

Both ships arrived safely at Cork on 17 May, Rear-Admiral Robert Kingsmill informing the Admiralty of the action by letter. Atalante subsequently served the Royal Navy as a 36-gun frigate under the name HMS Espion as there was already a ship named HMS Atalanta in service. For his lengthy and brave resistance, Linois was highly praised, particularly by the historian William James, who wrote in 1827 that Linois' "endeavours . . . were highly meritorious" and considered that in an engagement against a British frigate "the Atalante, if conquered at all, would have been dearly purchased." Shortly after his arrival in Britain, Linois was exchanged and returned to France.

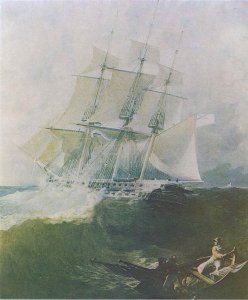

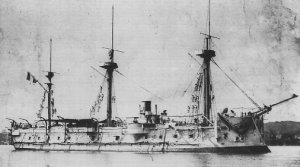

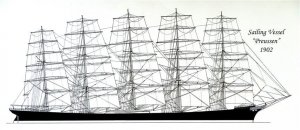

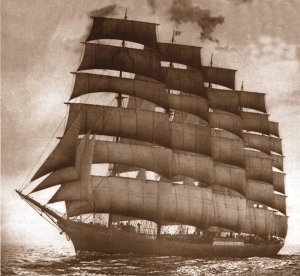

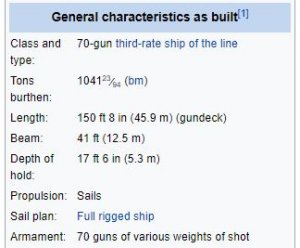

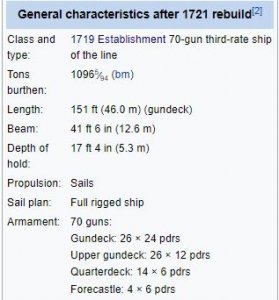

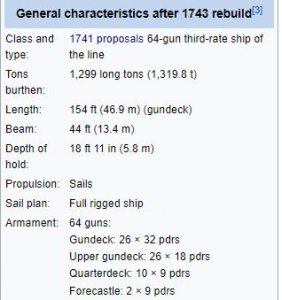

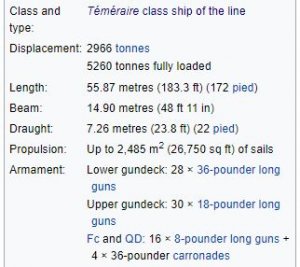

HMS Swiftsure was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the British Royal Navy. She spent most of her career serving with the British, except for a brief period when she was captured by the French during the Napoleonic Wars in the Action of 24 June 1801. She fought in several of the most famous engagements of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, fighting for the British at the Battle of the Nile, and the French at the Battle of Trafalgar

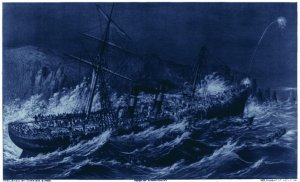

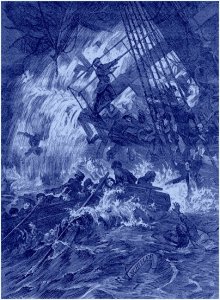

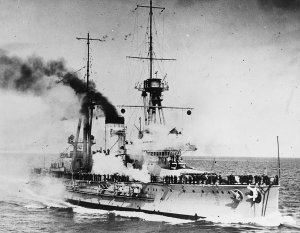

Orient explodes at the Nile. HMS Swiftsure is in the centre of the picture, sails billowing in the blast, and riding the wave caused by the force of the explosion.

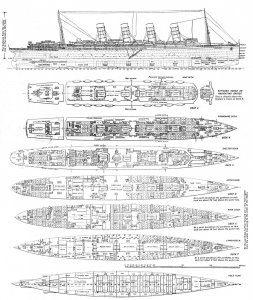

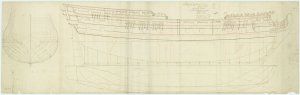

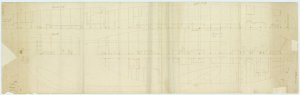

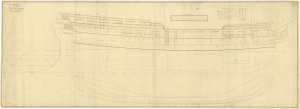

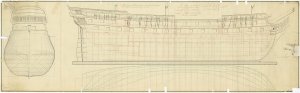

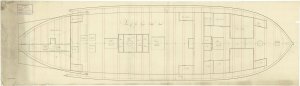

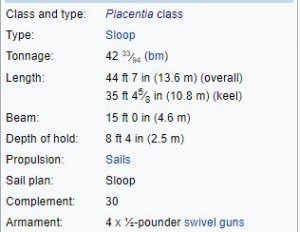

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Elizabeth' (1769), and with alterations for 'Resolution' (1770), 'Cumberland' (1774), 'Berwick' (1775), 'Bombay Castle' (1782), 'Defiance' (1783), 'Powerful' (1783), and 'Swiftsure' (1787), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers

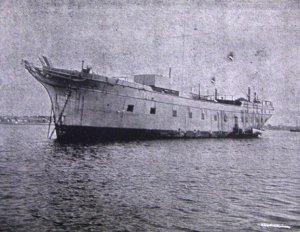

HMS St Albans was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 12 September 1764 at Blackwall Yard, London. She served in the American War of Independence from 1777 and was part of the fleet that captured St Lucia and won victories at Battle of St. Kitts and The Saintes. She was converted to a floating battery in 1803 and was broken up in 1814.

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Swiftsure_(1787)

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Swiftsure_(1787)

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-352020;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=S

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_St_Albans_(1764)

7 May 1794 - The Action of 7 May 1794 was a minor naval action fought between a British ship of the line and a French frigate early in the French Revolutionary Wars.

HMS Swiftsure (74), Captain Charles Boyles, captured Atalante (36), Cptn. Charles-Alexandre-Leon Durand-Linois

The Action of 7 May 1794 was a minor naval action fought between a British ship of the line and a French frigate early in the French Revolutionary Wars. The French Navy sought to disrupt British trade by intercepting and capturing merchant ships with roving frigates, a strategy countered by protecting British convoys with heavier warships, particularly in European waters. On 5 May 1794, the British escorts of a convoy from Cork sighted two French ships approaching and gave chase. The ships, a frigate and a corvette, outmatched by their opponents, separated and the convoy escorts did likewise, each following one of the raiders on a separate course.

By the evening one of the French ships had successfully escaped, but the other was still under pursuit, Captain Charles Linois of Atalante attempting a number of tactics to drive off his opponent but without success. Eventually, after a chase lasting nearly two days, the French ship came within range of the much larger British 74-gun third rate HMS Swiftsure and despite a brave defence was soon forced to surrender after suffering more than 40 casualties. Although he had surrendered his ship, Linois was widely praised for his actions in defending his ship against such heavy odds.

In the aftermath of the engagement, a French battle squadron that formed part of the developing Atlantic campaign of May 1794 pursued both ships for the rest of the day; their quarry eventually escaped after dark. Atalante was later taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Espion.

lines NMM, Progress Book, volume 5, folio 543, states that 'Espion' was at Plymouth Dockyard between March and My 1795 being fitted and having defects rectified, and there again in November 1795. She was in Sheerness Dockyard between 1 December 1796 and 16 January 1797 having further defects made good. In 1798 she was fitted as a floating battery and in 1799 as a troopship

Background

The outbreak of war between Britain and France in the spring of 1793 came at a time of differing fortunes for the navies of the two countries. The Royal Navy had been at a state of heightened readiness since 1792 in preparation for the conflict, while the French Navy had still not recovered from the upheavals of the French Revolution, which had resulted in the collapse of the naval hierarchy and a dearth of experienced officers and seamen. French naval strategy early in the war was to send squadrons and light vessels to operate along British trade routes, in order to disrupt British mercantile operations. This resulted in Britain forming its merchant ships into convoys for mutual protection, escorted by warships while in European waters to defend against roving attacks by French ships.

By the spring of 1794, France was in turmoil following the failure of the harvest, which threatened the country with starvation. In order to secure food supplies, France turned to its American colonies and the United States, which assembled a large grain convoy in Hampton Roads. To ensure the security of this convoy, the French Navy dispatched most of its Atlantic Fleet to sea during May 1794, operating in a series of large squadrons, independent cruisers and one major fleet under Villaret de Joyeuse. On 5 May, two French ships operating independently, the 36-gun frigate Atalante under Captain Charles Linois and the corvette Levrette, spied a British convoy sailing south-west, three days out from Cork, and closed to investigate.

Pursuit

The convoy that Linois had sighted was under the protection of two ships of the line, the Swiftsure under Captain Charles Boyles and the 64-gun HMS St Albans under Captain James Vashon. At 17:45, with the French frigates closing from the west and aware that they could not defend the whole convoy without immediate direct action, Boyles turned Swiftsure and St Albans towards the newcomers, hoisting their colours and Swiftsure firing three shots in the direction of the larger ship, Atalante. Together the British ships hugely outweighed and outmatched the French vessels, and as soon as Linois realised his mistake he gave orders for his ships to turn and make all sail to escape pursuit, raising the French tricolour and firing his stern-chasers, guns fitted in the rear of the ship, at his pursuers.

The French ships immediately separated. St Albans then followed Levrette while Swiftsure concentrated on Atalante. Throughout the rest of the evening the two chases continued. Then after darkness fell Levrette was able to outrun and escape from St Albans. Swiftsure however remained in touch with Atalante so that by 04:00 on 6 May the French frigate was approximately 2.5 nautical miles (4.6 km) ahead of the ship of the line to the northwest, with the wind direction to the north-northeast. For the entire following day Linois could not escape Boyles' pursuit, and at 17:30 Swiftsure was close enough to open fire again, using the bow-chasers for an hour and a half until Atalante once more pulled out of range. During the evening the French frigate was able to keep 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) in front of Swiftsure, but at midnight Linois switched his course to the south, hoping that the darkness would cloak the manoeuvre and that Atlante would be able to escape Boyles.

At 02:00 it became clear that Linois's ploy had failed and that Swiftsure was still following Atalante. More importantly, the manoeuvre had severely slowed the frigate. Although Linois hauled closer to the wind, Boyles was able to come within range at 02:30, firing his starboard guns into the smaller ship. Although his crew were exhausted by the extended chase Linois returned fire, the warships exchanging shot at long-range and the frigate suffering far more serious damage during the brief engagement. By 03:25 Linois was forced to surrender, his ship's rigging in tatters and casualties mounting among his crew. Boyles then provided a prize crew to the frigate and took most of the surviving French crew aboard his own ship as prisoners of war. Casualties on the French ship were heavy, with ten killed and 32 wounded from the 274 men aboard, compared to a single man lost on Swiftsure, which had also suffered some damage to its rigging.

Aftermath

Boyles was not long able to enjoy his victory undisturbed: at 10:00 on 7 May, shortly after the removal of the French prisoners had been completed, sails were spotted on the horizon. These were rapidly identified as three French ships of the line that were making all haste to intercept and capture Swiftsure and Atalante. These ships were part of a squadron under Contre-Admiral Joseph-Marie Nielly that had sailed from Rochefort the day before in search of the American grain convoy shortly due in European waters. Issuing rapid orders, Boyles instructed Atalante's prize crew to separate their ship from Swiftsure in order to force the French to split their forces; the frigate and the ship of the line fleeing on different courses. Atalante soon outran pursuit and escaped into the Atlantic, the prize crew even managing to replace the damaged main topsail in the midst of the chase with the assistance of the French prisoners on board. Swiftsure was slower but Boyles was still able to increase the distance between his vessel and the French during the day, finally losing sight of his pursuers at 22:00.

Both ships arrived safely at Cork on 17 May, Rear-Admiral Robert Kingsmill informing the Admiralty of the action by letter. Atalante subsequently served the Royal Navy as a 36-gun frigate under the name HMS Espion as there was already a ship named HMS Atalanta in service. For his lengthy and brave resistance, Linois was highly praised, particularly by the historian William James, who wrote in 1827 that Linois' "endeavours . . . were highly meritorious" and considered that in an engagement against a British frigate "the Atalante, if conquered at all, would have been dearly purchased." Shortly after his arrival in Britain, Linois was exchanged and returned to France.

HMS Swiftsure was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the British Royal Navy. She spent most of her career serving with the British, except for a brief period when she was captured by the French during the Napoleonic Wars in the Action of 24 June 1801. She fought in several of the most famous engagements of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, fighting for the British at the Battle of the Nile, and the French at the Battle of Trafalgar

Orient explodes at the Nile. HMS Swiftsure is in the centre of the picture, sails billowing in the blast, and riding the wave caused by the force of the explosion.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Elizabeth' (1769), and with alterations for 'Resolution' (1770), 'Cumberland' (1774), 'Berwick' (1775), 'Bombay Castle' (1782), 'Defiance' (1783), 'Powerful' (1783), and 'Swiftsure' (1787), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers

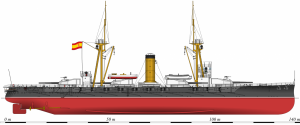

HMS St Albans was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 12 September 1764 at Blackwall Yard, London. She served in the American War of Independence from 1777 and was part of the fleet that captured St Lucia and won victories at Battle of St. Kitts and The Saintes. She was converted to a floating battery in 1803 and was broken up in 1814.

Action of 7 May 1794 - Wikipedia

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-352020;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=S

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_St_Albans_(1764)