Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

6 September 1842 – Launch of HMS Superb, a 80 gun Vanguard-class Ship of the Line

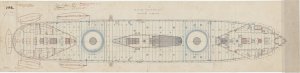

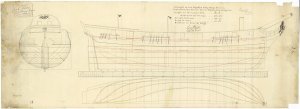

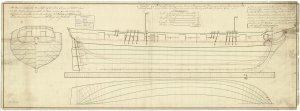

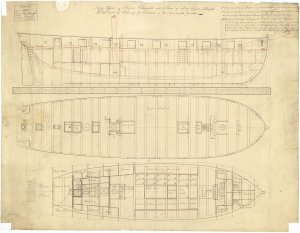

HMS Superb was a two-deck 80-gun second rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 6 September 1842 at Pembroke Dockyard.

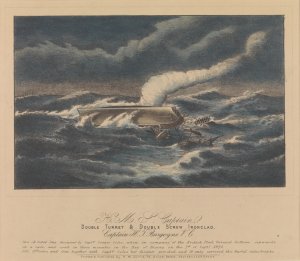

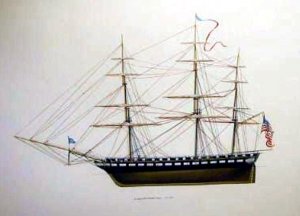

H.M.S Superb, (80 guns) sailing from Spithead, June 23rd 1845...(shows H.M.Y. Victoria & Albert and H.M.Steamer Black Eagle) (PAH0920)

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/140867.html#1eOmO0xuLMuWTlkg.99

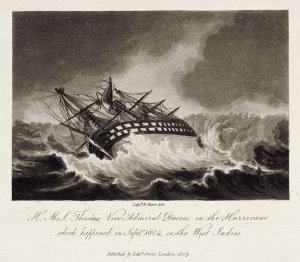

She was one of the Vanguard class, designed by Sir William Symonds, Surveyor of the Navy and an innovative and controversial naval architect. Each ship of the class was designed with a slightly different hull shape, aiming to optimise speed and handling characteristics. After Commissioning, Superb joined the Channel Fleet under the command of Captain Armar Lowry Corry. In February 1845, she joined the Experimental Squadron of eight ships, four of them built by Symonds. They engaged in three competitive cruises to test Symonds’ new hull designs against older, traditionally built warships. The whole Squadron was reviewed by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Spithead on 22 June and the trials were completed by December, Superb having proved to be the fastest ship in the last cruise. Overall, the results were inconclusive and became mired by political wrangling and professional rivalry, with the result that Symonds resigned. Superb took part in further trials the following year with yet more ships, this time called The Squadron of Evolution. The whole project was made irrelevant by the advent of steam propulsion and the Vanguard class were some of the last major Royal Navy warships to rely solely on sail propulsion.

Spithead June 19th 1845. Albion, Superb, Queen, Rodney, Trafalgar, Victoria & Albert, Canopus, St Vincent, Vanguard (PAD7790)

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/111941.html#iV12dU2Q7J0yXKtt.99

Returning to duties with the Channel Fleet, she saw action in the Portuguese "Little Civil War" or Patuleia in 1847, as part of a British squadron commanded by Sir William Parker, which was sent to support Queen Maria II. In May, a division of rebel troops commanded by the Conde das Antas was being ferried by sea along the coast, with the aim of securing the mouth of the River Tagus, thus blockading the capital. The convoy was intercepted by the British squadron and ordered to surrender. When Antas refused, boats’ crews put off from the British warships and boarded and captured all the transports, despite coming under fire from coastal batteries. Some three thousand rebel soldiers were disarmed and held in Fort St Julian under a guard of Royal Marines until relieved by loyal Portuguese troops.

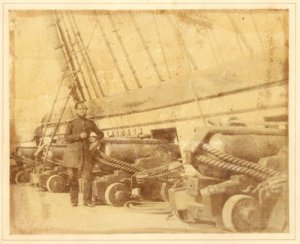

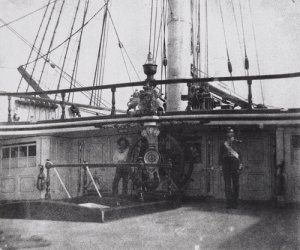

Officer on board the HMS Superb 1845

In November 1848, the Superb under Captain Edward Purcell joined the Mediterranean Fleet, and continued there until paying off into the reserve at Chatham in June 1852.

Superb was broken up in 1869.

The Vanguard-class ships of the line were a class of two-deck 80-gun second rates, designed for the Royal Navy by Sir William Symonds, of which nine were completed as sailing ships of the line, although another two of these were completed as (and others converted into) steam warships.

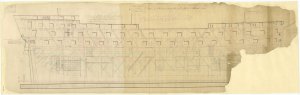

Royal Navy battleship HMS Collingwood (1841)

They were originally planned as 78-gun third rates. Two ships were ordered in 1832 and another two in 1833, although one of the latter was intended to be a rebuilding of the second rate Union, and this was subsequently cancelled. At this point the design was modified and they were re-designated as 80-gun second rates. Another ship was ordered to this design in 1838, another seven in 1839 (of which two were subsequently re-ordered three months later as 90-gun ships to a new design - the Albion and Aboukir) and another two in 1840. Two of the above ships were re-ordered and completed as steam battleships - Majesticand Irresistible. A final ship to this design, the Brunswick, was ordered in 1844 but in 1847 she was re-ordered to a modified design.

Ships

Launched: 25 August 1835

Fate: Broken up, 1875

Launched: 17 August 1841

Fate: Sold, 1867

Launched: 25 July 1842

Fate: Burnt, 1875

Launched: 6 September 1842

Fate: Broken up, 1869

Launched: 11 November 1848

Fate: Broken up, 1906

Launched: 2 May 1844

Fate: Sold, 1870

Launched: 29 July 1847

Fate: Sold, 1905

Launched: 1 June 1848

Fate: Sold, 1867

Launched: 1 July 1848

Fate: Sold, 1929

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Superb_(1842)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vanguard-class_ship_of_the_line

6 September 1842 – Launch of HMS Superb, a 80 gun Vanguard-class Ship of the Line

HMS Superb was a two-deck 80-gun second rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 6 September 1842 at Pembroke Dockyard.

H.M.S Superb, (80 guns) sailing from Spithead, June 23rd 1845...(shows H.M.Y. Victoria & Albert and H.M.Steamer Black Eagle) (PAH0920)

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/140867.html#1eOmO0xuLMuWTlkg.99

She was one of the Vanguard class, designed by Sir William Symonds, Surveyor of the Navy and an innovative and controversial naval architect. Each ship of the class was designed with a slightly different hull shape, aiming to optimise speed and handling characteristics. After Commissioning, Superb joined the Channel Fleet under the command of Captain Armar Lowry Corry. In February 1845, she joined the Experimental Squadron of eight ships, four of them built by Symonds. They engaged in three competitive cruises to test Symonds’ new hull designs against older, traditionally built warships. The whole Squadron was reviewed by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Spithead on 22 June and the trials were completed by December, Superb having proved to be the fastest ship in the last cruise. Overall, the results were inconclusive and became mired by political wrangling and professional rivalry, with the result that Symonds resigned. Superb took part in further trials the following year with yet more ships, this time called The Squadron of Evolution. The whole project was made irrelevant by the advent of steam propulsion and the Vanguard class were some of the last major Royal Navy warships to rely solely on sail propulsion.

Spithead June 19th 1845. Albion, Superb, Queen, Rodney, Trafalgar, Victoria & Albert, Canopus, St Vincent, Vanguard (PAD7790)

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/111941.html#iV12dU2Q7J0yXKtt.99

Returning to duties with the Channel Fleet, she saw action in the Portuguese "Little Civil War" or Patuleia in 1847, as part of a British squadron commanded by Sir William Parker, which was sent to support Queen Maria II. In May, a division of rebel troops commanded by the Conde das Antas was being ferried by sea along the coast, with the aim of securing the mouth of the River Tagus, thus blockading the capital. The convoy was intercepted by the British squadron and ordered to surrender. When Antas refused, boats’ crews put off from the British warships and boarded and captured all the transports, despite coming under fire from coastal batteries. Some three thousand rebel soldiers were disarmed and held in Fort St Julian under a guard of Royal Marines until relieved by loyal Portuguese troops.

Officer on board the HMS Superb 1845

In November 1848, the Superb under Captain Edward Purcell joined the Mediterranean Fleet, and continued there until paying off into the reserve at Chatham in June 1852.

Superb was broken up in 1869.

The Vanguard-class ships of the line were a class of two-deck 80-gun second rates, designed for the Royal Navy by Sir William Symonds, of which nine were completed as sailing ships of the line, although another two of these were completed as (and others converted into) steam warships.

Royal Navy battleship HMS Collingwood (1841)

They were originally planned as 78-gun third rates. Two ships were ordered in 1832 and another two in 1833, although one of the latter was intended to be a rebuilding of the second rate Union, and this was subsequently cancelled. At this point the design was modified and they were re-designated as 80-gun second rates. Another ship was ordered to this design in 1838, another seven in 1839 (of which two were subsequently re-ordered three months later as 90-gun ships to a new design - the Albion and Aboukir) and another two in 1840. Two of the above ships were re-ordered and completed as steam battleships - Majesticand Irresistible. A final ship to this design, the Brunswick, was ordered in 1844 but in 1847 she was re-ordered to a modified design.

Ships

Launched: 25 August 1835

Fate: Broken up, 1875

Launched: 17 August 1841

Fate: Sold, 1867

Launched: 25 July 1842

Fate: Burnt, 1875

Launched: 6 September 1842

Fate: Broken up, 1869

Launched: 11 November 1848

Fate: Broken up, 1906

Launched: 2 May 1844

Fate: Sold, 1870

Launched: 29 July 1847

Fate: Sold, 1905

Launched: 1 June 1848

Fate: Sold, 1867

Launched: 1 July 1848

Fate: Sold, 1929

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Superb_(1842)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vanguard-class_ship_of_the_line

paper

paper