Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

8 September1934 – Off the New Jersey coast, a fire aboard the passenger liner SS Morro Castle kills 137 people.

EL Morro Castle was an ocean liner of the 1930s that was built for the Ward Line for voyages between New York City and Havana, Cuba. The ship was named for the Morro Castle fortress that guards the entrance to Havana Bay. On the morning of September 8, 1934, en route from Havana to New York, the ship caught fire and burned, killing 137 passengers and crew members. The ship eventually beached herself near Asbury Park, New Jersey, and remained there for several months until she was towed off and scrapped.

The devastating fire aboard the TEL Morro Castle was a catalyst for improved shipboard fire safety. Today, the use of fire-retardant materials, automatic fire doors, ship-wide fire alarms, and greater attention to fire drills and procedures resulted directly from the Morro Castle disaster.

Building of TEL Morro Castle

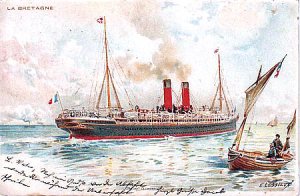

On May 22, 1928, the U.S. Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1928, creating a $250 million construction fund to be lent to U.S. shipping companies to replace old and outdated ships with new ones. Each of these loans, which could subsidize as much as 75% of the cost of the ship, was to be paid back over 20 years at very low interest rates. One company that quickly availed itself of this opportunity was the Ward Line (officially: the New York and Cuba Mail Steam Ship Company), which had been carrying passengers, cargo and mail to and from Cuba since the mid-19th century. Naval architects were hired by the line to design a pair of passenger and cargo liners to be named TEL Morro Castle after the stone fortress and lighthouse in Havana and TEL Oriente after Oriente Province in Cuba.

At the Newport Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, work was begun on Morro Castle in January 1929. In March 1930 Morro Castle was christened, followed in May by her sister ship Oriente. Each ship was 508 feet (155 metres) long, measured 11,520 gross register tons (GRT) and had turbo-electric transmission, with General Electric twin turbo generators supplying current to propulsion motors on twin propeller shafts. Each ship was luxuriously finished to accommodate 489 passengers in first and tourist class, along with 240 crew members and officers. The cost of each ship was estimated at about $5 million. In a growing age of passenger ships having cruiser sterns, Morro Castle and Oriente were constructed with the classic counter sterns.

Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, work was begun on Morro Castle in January 1929. In March 1930 Morro Castle was christened, followed in May by her sister ship Oriente. Each ship was 508 feet (155 metres) long, measured 11,520 gross register tons (GRT) and had turbo-electric transmission, with General Electric twin turbo generators supplying current to propulsion motors on twin propeller shafts. Each ship was luxuriously finished to accommodate 489 passengers in first and tourist class, along with 240 crew members and officers. The cost of each ship was estimated at about $5 million. In a growing age of passenger ships having cruiser sterns, Morro Castle and Oriente were constructed with the classic counter sterns.

Disaster strikes the TEL Morro Castle

Impending nor'easter

The final voyage of Morro Castle began in Havana on September 5, 1934. On the afternoon of the 6th, as the ship paralleled the southeastern coast of the United States, it began to encounter increasing clouds and wind. By the morning of the 7th, the clouds had thickened and the winds had shifted to easterly, the first indication of a developing nor'easter. Throughout that day, the winds increased and intermittent rains began, causing many to retire early to their berths.

Captain's death

Early that evening, Captain Robert Willmott had his dinner delivered to his quarters. Shortly thereafter, he complained of stomach trouble and, not long after that, died of an apparent heart attack. Command of the ship passed to the Chief Officer, William Warms. During the overnight hours, the winds increased to over 30 miles per hour as the Morro Castle plodded its way up the eastern seaboard.

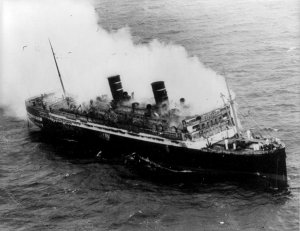

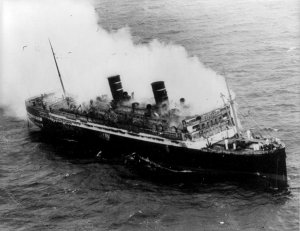

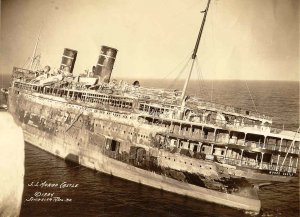

TEL Morro Castle on fire, September 8, 1934.

Fire

At around 2:50 a.m. on September 8, while the ship was sailing around eight nautical miles off Long Beach Island, a fire was detected in a storage locker within the First Class Writing Room on B Deck. Within the next 30 minutes, the Morro Castle became engulfed in flames. As the fire grew in intensity, Acting Captain Warms attempted to beach the ship, but the growing need to launch lifeboats and abandon ship forced him to give up this strategy. Within 20 minutes of the fire's discovery (at about 3:10), the fire burned through the ship's main electrical cables, plunging the ship into darkness. As all power was lost, the radio stopped working as well, so that the crew were cut off from radio contact after issuing a single SOS transmission. At about the same time, the wheelhouse lost the ability to steer the ship, as those hydraulic lines were severed by the fire as well.[5]:40 Cut off by the fire amidships, passengers tended to gravitate toward the stern. Most crew members, on the other hand, moved to the forecastle.[5]:48 On the ship, no one could see anything. In many places, the deck boards were hot to the touch, and breathing was challenging in the thick smoke. As conditions grew steadily worse, the decision became either "jump or burn" for many passengers. However, jumping into the water was problematic as well. The sea, whipped by high winds, churned in great waves that made swimming extremely difficult.

On the decks of the burning ship, the crew and passengers exhibited the full range of reactions to the disaster at hand. Some crew members were incredibly brave as they tried to fight the fire. Others tossed deck chairs and life rings overboard to provide persons in the water with makeshift flotation devices.[5]:50

Only six of the ship's 12 lifeboats were launched: boats 1, 3, 5, 9, and 11 on the starboard side, and boat 10 on the port side. Although the combined capacity of these boats was 408, they carried only 85 people, most of them crew members. Many passengers died for lack of knowledge of how to use the life preservers. As they hit the water, life preservers knocked many persons unconscious, leading to subsequent death by drowning, or broke victims' necks from the impact, killing them instantly.

Rescue efforts at sea

The rescuers were slow to react. The first rescue ship to arrive on the scene was the SS Andrea F. Luckenbach. Two other ships—the SS Monarch of Bermuda and the SS City of Savannah—were slow in taking action after receiving the SOS but eventually did arrive on the scene. The fourth ship to participate in the rescue operations was the SS President Cleveland, which launched a motor boat that made a cursory circuit around the Morro Castle and, upon seeing nobody in the water along her route, retrieved her motor boat and left the scene.

The Coast Guard vessels Tampa and Cahoone positioned themselves too far away to see the victims in the water and rendered little assistance. The Coast Guard's aerial station at Cape May, New Jersey, failed to send their float planes until local radio stations started reporting that dead bodies were washing ashore on the New Jersey beaches, from Point Pleasant Beach to Spring Lake.

In time, additional small boats arrived on the scene. The large ocean swells presented a major problem, making it very difficult to see people in the water. A plane piloted by Harry Moore, Governor of New Jersey and Commander of the New Jersey Guard,[clarification needed] helped boats to find survivors and bodies by dipping its wings and dropping markers.

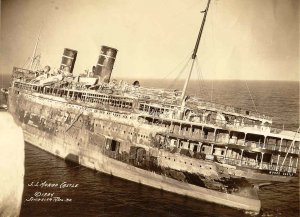

SS Morro Castle after the fire; photo taken from the seaward end of the Asbury Park Convention Hall pier, November 1934.

Recovery efforts on shore

As telephone calls and radio stations spread news of the disaster along the New Jersey coast, local citizens assembled on the coastline to nurse the wounded, retrieve the dead, and try to unite families that had been scattered among different rescue boats that landed on the New Jersey beaches.

By mid-morning, the ship was totally abandoned and its burning hull drifted ashore, coming to a stop in shallow water off Asbury Park, New Jersey, late that afternoon at almost the exact spot where the New Era had wrecked in 1854. The fires continued to smoulder for the next two days, and in the end, 135 passengers and crew (out of a total of 549) were lost.

The ship was declared a total loss, and its charred hulk was finally towed away from the Asbury Park shoreline on March 14, 1935. According to one account, it later started settling by the stern and sank while being towed.

In the intervening months, because of its proximity to the boardwalk and the Asbury Park Convention Hall pier, from which it was possible to wade out and touch the wreck with one's hands, the wreck was treated as a destination for sightseeing trips, complete with stamped penny souvenirs and postcards for sale.[8] (Other accounts have it that the ship was towed to Gravesend Bay on March 14, 1935, after serving as an Asbury Park attraction, and then to Baltimore on the 29th, where it was scrapped.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Morro_Castle_(1930)

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/ss-morro-castle-burnt-1934/

8 September1934 – Off the New Jersey coast, a fire aboard the passenger liner SS Morro Castle kills 137 people.

EL Morro Castle was an ocean liner of the 1930s that was built for the Ward Line for voyages between New York City and Havana, Cuba. The ship was named for the Morro Castle fortress that guards the entrance to Havana Bay. On the morning of September 8, 1934, en route from Havana to New York, the ship caught fire and burned, killing 137 passengers and crew members. The ship eventually beached herself near Asbury Park, New Jersey, and remained there for several months until she was towed off and scrapped.

The devastating fire aboard the TEL Morro Castle was a catalyst for improved shipboard fire safety. Today, the use of fire-retardant materials, automatic fire doors, ship-wide fire alarms, and greater attention to fire drills and procedures resulted directly from the Morro Castle disaster.

Building of TEL Morro Castle

On May 22, 1928, the U.S. Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1928, creating a $250 million construction fund to be lent to U.S. shipping companies to replace old and outdated ships with new ones. Each of these loans, which could subsidize as much as 75% of the cost of the ship, was to be paid back over 20 years at very low interest rates. One company that quickly availed itself of this opportunity was the Ward Line (officially: the New York and Cuba Mail Steam Ship Company), which had been carrying passengers, cargo and mail to and from Cuba since the mid-19th century. Naval architects were hired by the line to design a pair of passenger and cargo liners to be named TEL Morro Castle after the stone fortress and lighthouse in Havana and TEL Oriente after Oriente Province in Cuba.

At the Newport

Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, work was begun on Morro Castle in January 1929. In March 1930 Morro Castle was christened, followed in May by her sister ship Oriente. Each ship was 508 feet (155 metres) long, measured 11,520 gross register tons (GRT) and had turbo-electric transmission, with General Electric twin turbo generators supplying current to propulsion motors on twin propeller shafts. Each ship was luxuriously finished to accommodate 489 passengers in first and tourist class, along with 240 crew members and officers. The cost of each ship was estimated at about $5 million. In a growing age of passenger ships having cruiser sterns, Morro Castle and Oriente were constructed with the classic counter sterns.

Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, work was begun on Morro Castle in January 1929. In March 1930 Morro Castle was christened, followed in May by her sister ship Oriente. Each ship was 508 feet (155 metres) long, measured 11,520 gross register tons (GRT) and had turbo-electric transmission, with General Electric twin turbo generators supplying current to propulsion motors on twin propeller shafts. Each ship was luxuriously finished to accommodate 489 passengers in first and tourist class, along with 240 crew members and officers. The cost of each ship was estimated at about $5 million. In a growing age of passenger ships having cruiser sterns, Morro Castle and Oriente were constructed with the classic counter sterns.Disaster strikes the TEL Morro Castle

Impending nor'easter

The final voyage of Morro Castle began in Havana on September 5, 1934. On the afternoon of the 6th, as the ship paralleled the southeastern coast of the United States, it began to encounter increasing clouds and wind. By the morning of the 7th, the clouds had thickened and the winds had shifted to easterly, the first indication of a developing nor'easter. Throughout that day, the winds increased and intermittent rains began, causing many to retire early to their berths.

Captain's death

Early that evening, Captain Robert Willmott had his dinner delivered to his quarters. Shortly thereafter, he complained of stomach trouble and, not long after that, died of an apparent heart attack. Command of the ship passed to the Chief Officer, William Warms. During the overnight hours, the winds increased to over 30 miles per hour as the Morro Castle plodded its way up the eastern seaboard.

TEL Morro Castle on fire, September 8, 1934.

Fire

At around 2:50 a.m. on September 8, while the ship was sailing around eight nautical miles off Long Beach Island, a fire was detected in a storage locker within the First Class Writing Room on B Deck. Within the next 30 minutes, the Morro Castle became engulfed in flames. As the fire grew in intensity, Acting Captain Warms attempted to beach the ship, but the growing need to launch lifeboats and abandon ship forced him to give up this strategy. Within 20 minutes of the fire's discovery (at about 3:10), the fire burned through the ship's main electrical cables, plunging the ship into darkness. As all power was lost, the radio stopped working as well, so that the crew were cut off from radio contact after issuing a single SOS transmission. At about the same time, the wheelhouse lost the ability to steer the ship, as those hydraulic lines were severed by the fire as well.[5]:40 Cut off by the fire amidships, passengers tended to gravitate toward the stern. Most crew members, on the other hand, moved to the forecastle.[5]:48 On the ship, no one could see anything. In many places, the deck boards were hot to the touch, and breathing was challenging in the thick smoke. As conditions grew steadily worse, the decision became either "jump or burn" for many passengers. However, jumping into the water was problematic as well. The sea, whipped by high winds, churned in great waves that made swimming extremely difficult.

On the decks of the burning ship, the crew and passengers exhibited the full range of reactions to the disaster at hand. Some crew members were incredibly brave as they tried to fight the fire. Others tossed deck chairs and life rings overboard to provide persons in the water with makeshift flotation devices.[5]:50

Only six of the ship's 12 lifeboats were launched: boats 1, 3, 5, 9, and 11 on the starboard side, and boat 10 on the port side. Although the combined capacity of these boats was 408, they carried only 85 people, most of them crew members. Many passengers died for lack of knowledge of how to use the life preservers. As they hit the water, life preservers knocked many persons unconscious, leading to subsequent death by drowning, or broke victims' necks from the impact, killing them instantly.

Rescue efforts at sea

The rescuers were slow to react. The first rescue ship to arrive on the scene was the SS Andrea F. Luckenbach. Two other ships—the SS Monarch of Bermuda and the SS City of Savannah—were slow in taking action after receiving the SOS but eventually did arrive on the scene. The fourth ship to participate in the rescue operations was the SS President Cleveland, which launched a motor boat that made a cursory circuit around the Morro Castle and, upon seeing nobody in the water along her route, retrieved her motor boat and left the scene.

The Coast Guard vessels Tampa and Cahoone positioned themselves too far away to see the victims in the water and rendered little assistance. The Coast Guard's aerial station at Cape May, New Jersey, failed to send their float planes until local radio stations started reporting that dead bodies were washing ashore on the New Jersey beaches, from Point Pleasant Beach to Spring Lake.

In time, additional small boats arrived on the scene. The large ocean swells presented a major problem, making it very difficult to see people in the water. A plane piloted by Harry Moore, Governor of New Jersey and Commander of the New Jersey Guard,[clarification needed] helped boats to find survivors and bodies by dipping its wings and dropping markers.

SS Morro Castle after the fire; photo taken from the seaward end of the Asbury Park Convention Hall pier, November 1934.

Recovery efforts on shore

As telephone calls and radio stations spread news of the disaster along the New Jersey coast, local citizens assembled on the coastline to nurse the wounded, retrieve the dead, and try to unite families that had been scattered among different rescue boats that landed on the New Jersey beaches.

By mid-morning, the ship was totally abandoned and its burning hull drifted ashore, coming to a stop in shallow water off Asbury Park, New Jersey, late that afternoon at almost the exact spot where the New Era had wrecked in 1854. The fires continued to smoulder for the next two days, and in the end, 135 passengers and crew (out of a total of 549) were lost.

The ship was declared a total loss, and its charred hulk was finally towed away from the Asbury Park shoreline on March 14, 1935. According to one account, it later started settling by the stern and sank while being towed.

In the intervening months, because of its proximity to the boardwalk and the Asbury Park Convention Hall pier, from which it was possible to wade out and touch the wreck with one's hands, the wreck was treated as a destination for sightseeing trips, complete with stamped penny souvenirs and postcards for sale.[8] (Other accounts have it that the ship was towed to Gravesend Bay on March 14, 1935, after serving as an Asbury Park attraction, and then to Baltimore on the 29th, where it was scrapped.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Morro_Castle_(1930)

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/ss-morro-castle-burnt-1934/

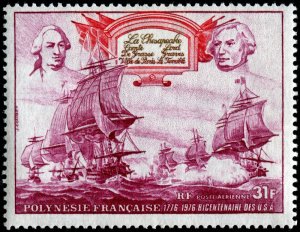

, and seizing me, holding naked Bayonets at my Breast, tied my Hands behind my back, and threatened instant destruction if I uttered a word. I however call'd loudly for assistance, but the conspiracy was so well laid that the Officers Cabbin Doors were guarded by Centinels, so Nelson, Peckover, Samuels or the Master could not come to me. I was now dragged on Deck in my Shirt & closely guarded – I demanded of Christian the case of such a violent act, & severely degraded for his Villainy but he could only answer – "not a word sir or you are Dead." I dared him to the act & endeavoured to rally some one to a sense of their duty but to no effect....

, and seizing me, holding naked Bayonets at my Breast, tied my Hands behind my back, and threatened instant destruction if I uttered a word. I however call'd loudly for assistance, but the conspiracy was so well laid that the Officers Cabbin Doors were guarded by Centinels, so Nelson, Peckover, Samuels or the Master could not come to me. I was now dragged on Deck in my Shirt & closely guarded – I demanded of Christian the case of such a violent act, & severely degraded for his Villainy but he could only answer – "not a word sir or you are Dead." I dared him to the act & endeavoured to rally some one to a sense of their duty but to no effect....

(1797 - 10), Edward Ellicot, wrecked on a reef near Sandy Island, Heligoland.

(1797 - 10), Edward Ellicot, wrecked on a reef near Sandy Island, Heligoland.