Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

28 May 1588 – The Spanish Armada, with 130 ships and 30,000 men, sets sail from Lisbon, Portugal, heading for the English Channel.

(It will take until May 30 for all ships to leave port.)

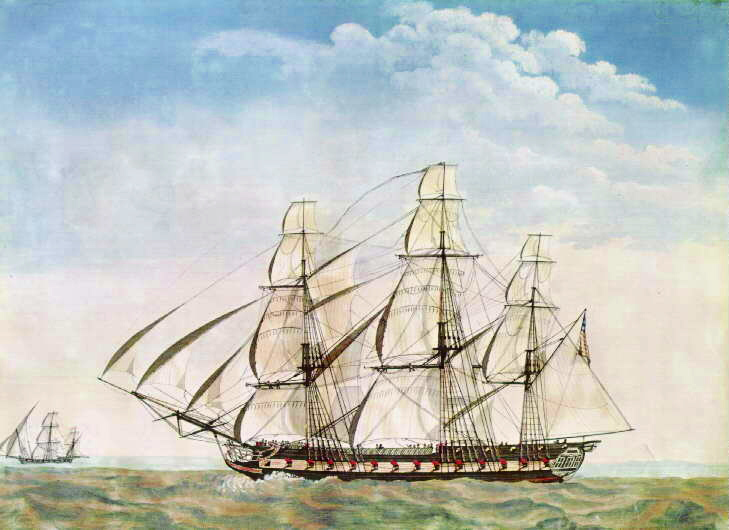

The Spanish Armada (Spanish: Grande y Felicísima Armada, lit. 'Great and Most Fortunate Navy') was a Habsburg Spanish fleet of 130 ships that sailed from Corunna in late May 1588, under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia, with the purpose of escorting an army from Flanders to invade England. Medina Sidonia was an aristocrat without naval command experience but was made commander by King Philip II. The aim was to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I and her establishment of Protestantism in England, to stop English interference in the Spanish Netherlands and to stop the harm caused by English and Dutch privateering ships that interfered with Spanish interests in America.

English ships sailed from Plymouth to attack the Armada and were faster and more manoeuvrable than the larger Spanish Galleons, enabling them to fire on the Armada without loss as it sailed east off the south coast of England. Armada could have anchored in the Solent between the Isle of Wight and the English mainland and occupied the Isle of Wight, but Medina Sidonia was under orders from King Philip II to meet up with the Duke of Parma's forces in The Netherlands so England could be invaded by Parma's soldiers and other soldiers carried in ships of the Armada. English guns damaged the Armada and a Spanish ship was captured by Sir Francis Drake in the English Channel.

The Armada anchored off Calais. While awaiting communications from Duke of Parma, the Armada was scattered by an English fireship night attack and abandoned its rendezvous with Parma's army, that was blockaded in harbour by Dutch flyboats. In the ensuing Battle of Gravelines, the Spanish fleet was further damaged and was in risk of running aground on the Dutch coast when the wind changed. The Armada, driven by southwest winds, withdrew north, with the English fleet harrying it up the east coast of England. On return to Spain round the north of Scotland and south around Ireland, the Armada was disrupted further by storms. A large number of ships were wrecked on the coasts of Scotland and Ireland and more than a third of the initial 130 ships failed to return.[26] As Martin and Parker explain, "Philip II attempted to invade England, but his plans miscarried. This was due to his own mismanagement, including appointing an aristocrat without naval experience as commander of the Armada, unfortunate weather, and the opposition of the English and their Dutch allies including the use of fire-ships sailed into the anchored Armada.".

The expedition was the largest engagement of the undeclared Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). The following year, England organised a similar large-scale campaign against Spain, the English Armada, sometimes called the "counter-Armada of 1589".

Etymology

The word armada is from the Spanish: armada, which is cognate with English army. Originally from the Latin: armāta, the past participle of armāre, 'to arm', used in Romance languages as a noun for armed force, army, navy, fleet. Armada Española is still the Spanish term for the modern Spanish Navy. Armada (originally from its armadas) was also the Portuguese traditional term (now alternative, but in common use) of the Portuguese Navy.

History

Background

Henry VIII began the English Reformation as a political exercise over his desire to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Over time, it became increasingly aligned with the Protestant reformation taking place in Europe, especially during the reign of Henry's son, Edward VI. Edward died childless and his half-sister, Mary I, ascended the throne. A devout Catholic, Mary, with her co-monarch and husband, Philip II of Spain, began to reassert Roman influence over church affairs. Her attempts led to more than 260 people being burned at the stake, earning her the nickname 'Bloody Mary'.

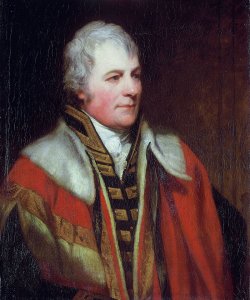

Philip II of Spain c. 1580, National Portrait Gallery, London

Mary's death in 1558 led to her half-sister, Elizabeth I, taking the throne. Unlike Mary, Elizabeth was firmly in the reformist camp, and quickly reimplemented many of Edward's reforms. Philip, no longer co-monarch, deemed Elizabeth a heretic and illegitimate ruler of England. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, Henry had never officially divorced Catherine, making Elizabeth illegitimate. It is alleged that Phillip supported plots to have Elizabeth overthrown in favour of her Catholic cousin and heir presumptive, Mary, Queen of Scots. These plans were thwarted when Elizabeth had the Queen of Scots imprisoned and executed in 1587. Elizabeth retaliated against Philip by supporting the Dutch revoltagainst Spain, as well as funding privateers to raid Spanish ships across the Atlantic.

In retaliation, Philip planned an expedition to invade England in order to overthrow Elizabeth and, if the Armada was not entirely successful, at least negotiate freedom of worship for Catholics and financial compensation for war in the Low Countries.[30] Through this endeavor, English material support for the United Provinces, the part of the Low Countries that had successfully seceded from Spanish rule, and English attacks on Spanish trade and settlements in the New World would end. The King was supported by Pope Sixtus V, who treated the invasion as a crusade, with the promise of a subsidy should the Armada make land.

A raid on Cádiz, led by Francis Drake in April 1587, had captured or destroyed about 30 ships and great quantities of supplies, setting preparations back by a year. Philip initially favoured a triple attack, starting with a diversionary raid on Scotland, while the main Armada would capture the Isle of Wight, or Southampton, to establish a safe anchorage in the Solent. The Duke of Parma would then follow with a large army from the Low Countries crossing the English Channel. Parma was uneasy about mounting such an invasion without any possibility of surprise. The appointed commander of the Armada was the highly experienced Álvaro de Bazán, Marquis of Santa Cruz, but he died in February 1588, and the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a high-born courtier, took his place. While a competent soldier and distinguished administrator, Medina Sidonia had no naval experience. He wrote to Philip expressing grave doubts about the planned campaign, but his message was prevented from reaching the King by courtiers on the grounds that God would ensure the Armada's success.

Planned invasion of England

See also: List of ships of the Spanish Armada

Route taken by the Spanish Armada

Prior to the undertaking, Pope Sixtus V allowed Philip II of Spain to collect crusade taxes and granted his men indulgences. The blessing of the Armada's banner on 25 April 1588 was similar to the ceremony used prior to the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

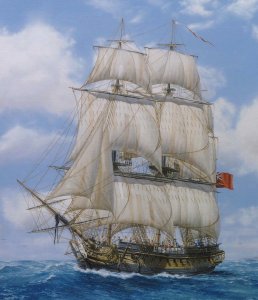

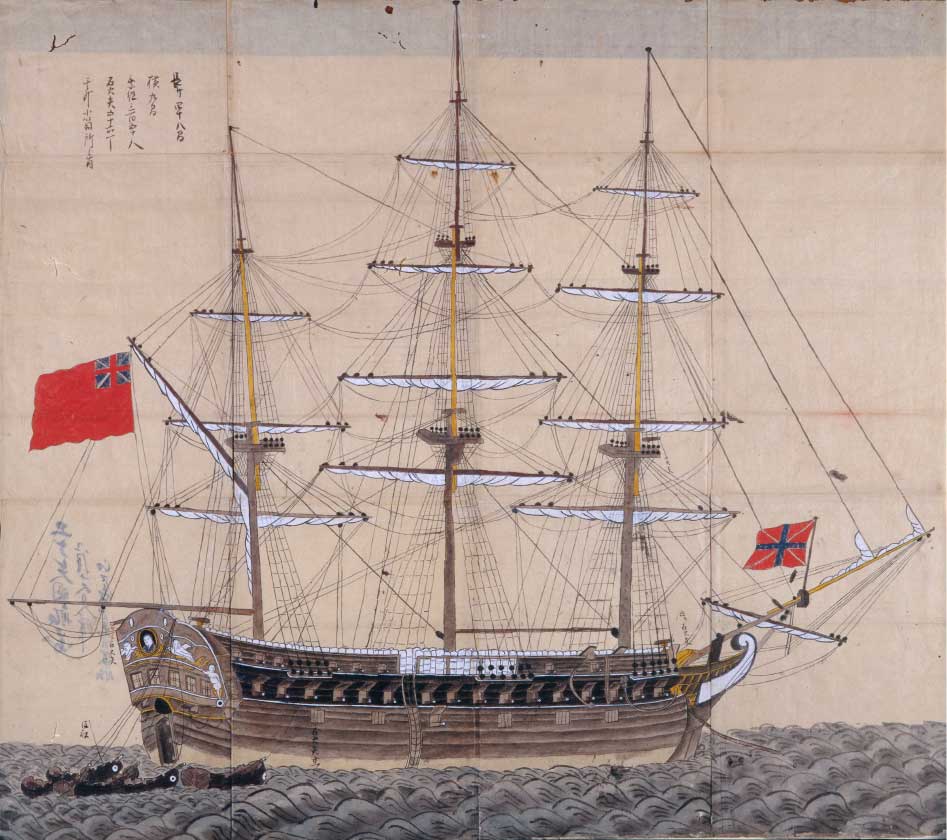

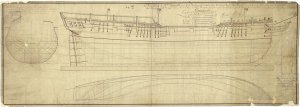

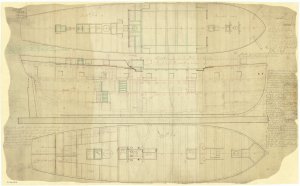

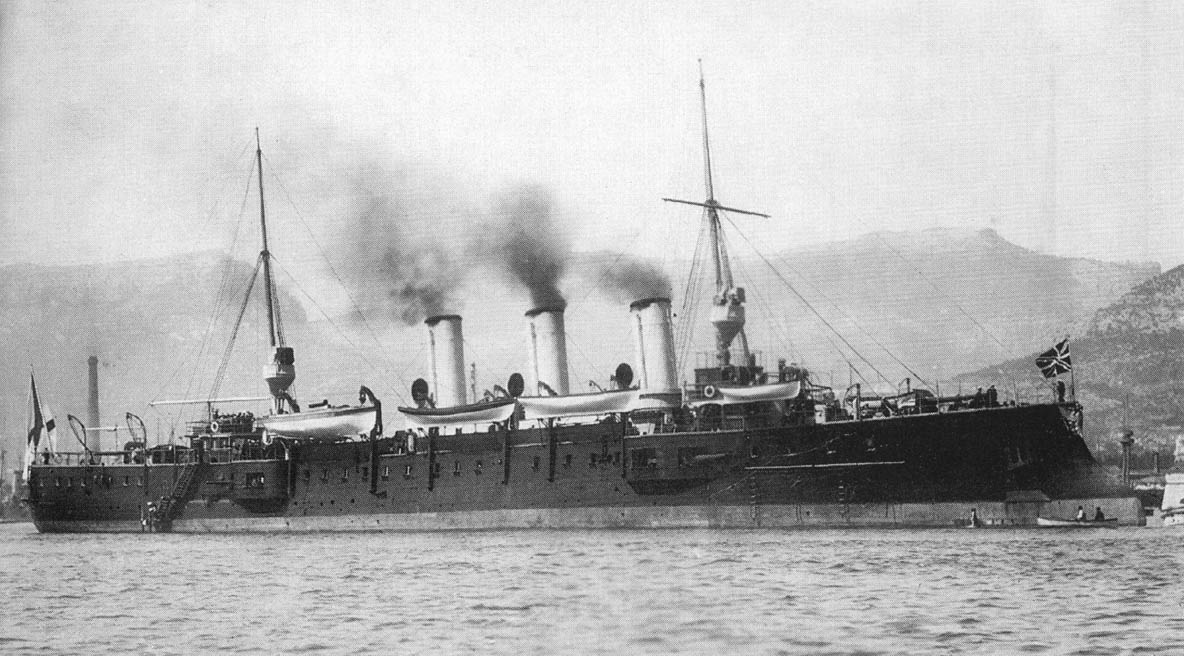

On 28 May 1588, the Armada set sail from Lisbon and headed for the English Channel. The fleet was composed of 130 ships, 8,000 sailors and 18,000 soldiers, and bore 1,500 brass guns and 1,000 iron guns. The full body of the fleet took two days to leave port. It included 28 purpose-built warships, of which 20 were galleons, four galleys and four (Neapolitan) galleasses. The remainder of the heavy vessels were mostly armed carracks and hulks together with 34 light ships.

In the Spanish Netherlands, 30,000 soldiers awaited the arrival of the Armada, the plan being to use the cover of the warships to convey the army on barges to a place near London. In all, 55,000 men were to have been mustered, a huge army for that time. On the day the Armada set sail, Elizabeth's ambassador in the Netherlands, Valentine Dale, met Parma's representatives in peace negotiations. The English made a vain effort to intercept the Armada in the Bay of Biscay. On 6 July negotiations were abandoned and the English fleet stood prepared, if ill-supplied, at Plymouth, awaiting news of Spanish movements. The English fleet outnumbered the Spanish, 200 ships to 130,[37] while the Spanish fleet outgunned the English. The Spanish available firepower was 50 percent more than that of the English.[38] The English fleet consisted of the 34 ships of the Royal Fleet, 21 of which were galleons of 200 to 400 tons, and 163 other ships, 30 of which were of 200 to 400 tons and carried up to 42 guns each. Twelve of the ships were privateers owned by Lord Howard of Effingham, Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake.

Signal station built in 1588, above the Devon village of Culmstock, to warn when the Armada was sighted

The Armada was delayed by bad weather. Storms in the Bay of Biscay forced four galleys and one galleon to turn back, and other ships had to put in for repairs, leaving only about 124 ships to actually make it to the English Channel. Nearly half the fleet were not built as warships and were used for duties such as scouting and dispatch work, or for carrying supplies, animals, and troops.

The fleet was sighted in England on 19 July, when it appeared off The Lizard in Cornwall. The news was conveyed to London by a system of beacons that had been constructed all the way along the south coast. On 19 July, the English fleet was trapped in Plymouth Harbour by the incoming tide. The Spanish convened a council of war, where it was proposed to ride into the harbour on the tide and incapacitate the defending ships at anchor. From Plymouth Harbour the Spanish would attack England, but Philip II explicitly forbidden Medina Sidonia to act, leaving the Armada to sail on to the east and toward the Isle of Wight. As the tide turned, 55 English ships set out to confront the Armada from Plymouth under the command of Lord Howard of Effingham, with Sir Francis Drake as Vice Admiral. The rear admiral was Sir John Hawkins.

..... please read about the further process in wikipedia .....

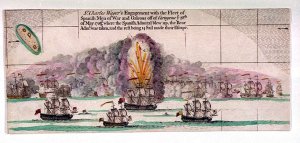

English fireships are launched at the Spanish armada off Calais

List of ships of the Spanish Armada

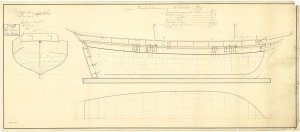

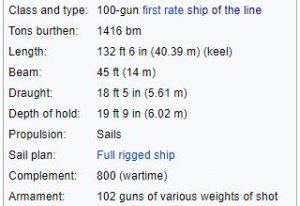

The armada that attempted to escort an army from Flanders and integrate the Habsburg Spanish invasion of England in 1588, was divided into ten "squadrons" (escuadras) The twenty galleons in the Squadrons of Portugal and of Castile, together with the four galleasses from Naples, constituted the only purpose-built warships (apart from the four galleys, which proved ineffective in the Atlantic waters and soon departed for safety in French ports); the rest of the Armada comprised armed merchantmen (mostly carracks) and various ancillary vessels including urcas (storeships, termed "hulks"), zabras and pataches, pinnaces, and (not included in the formal count) caravels. The division into squadrons was for administrative purposes only; upon sailing, the Armada could not keep to a formal order, and most ships sailed independently from the rest of their squadron.

This list is compiled by a survey drawn up by Medina Sidonia on the Armada's departure from Lisbon on 9 May 1588 and sent to Felipe II; it was then published and quickly became available to the English. The numbers of sailors and soldiers mentioned below are as given in the same survey and thus also relate to this date.

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ships_of_the_Spanish_Armada

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ships_of_the_Spanish_Armada

28 May 1588 – The Spanish Armada, with 130 ships and 30,000 men, sets sail from Lisbon, Portugal, heading for the English Channel.

(It will take until May 30 for all ships to leave port.)

The Spanish Armada (Spanish: Grande y Felicísima Armada, lit. 'Great and Most Fortunate Navy') was a Habsburg Spanish fleet of 130 ships that sailed from Corunna in late May 1588, under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia, with the purpose of escorting an army from Flanders to invade England. Medina Sidonia was an aristocrat without naval command experience but was made commander by King Philip II. The aim was to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I and her establishment of Protestantism in England, to stop English interference in the Spanish Netherlands and to stop the harm caused by English and Dutch privateering ships that interfered with Spanish interests in America.

English ships sailed from Plymouth to attack the Armada and were faster and more manoeuvrable than the larger Spanish Galleons, enabling them to fire on the Armada without loss as it sailed east off the south coast of England. Armada could have anchored in the Solent between the Isle of Wight and the English mainland and occupied the Isle of Wight, but Medina Sidonia was under orders from King Philip II to meet up with the Duke of Parma's forces in The Netherlands so England could be invaded by Parma's soldiers and other soldiers carried in ships of the Armada. English guns damaged the Armada and a Spanish ship was captured by Sir Francis Drake in the English Channel.

The Armada anchored off Calais. While awaiting communications from Duke of Parma, the Armada was scattered by an English fireship night attack and abandoned its rendezvous with Parma's army, that was blockaded in harbour by Dutch flyboats. In the ensuing Battle of Gravelines, the Spanish fleet was further damaged and was in risk of running aground on the Dutch coast when the wind changed. The Armada, driven by southwest winds, withdrew north, with the English fleet harrying it up the east coast of England. On return to Spain round the north of Scotland and south around Ireland, the Armada was disrupted further by storms. A large number of ships were wrecked on the coasts of Scotland and Ireland and more than a third of the initial 130 ships failed to return.[26] As Martin and Parker explain, "Philip II attempted to invade England, but his plans miscarried. This was due to his own mismanagement, including appointing an aristocrat without naval experience as commander of the Armada, unfortunate weather, and the opposition of the English and their Dutch allies including the use of fire-ships sailed into the anchored Armada.".

The expedition was the largest engagement of the undeclared Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). The following year, England organised a similar large-scale campaign against Spain, the English Armada, sometimes called the "counter-Armada of 1589".

Etymology

The word armada is from the Spanish: armada, which is cognate with English army. Originally from the Latin: armāta, the past participle of armāre, 'to arm', used in Romance languages as a noun for armed force, army, navy, fleet. Armada Española is still the Spanish term for the modern Spanish Navy. Armada (originally from its armadas) was also the Portuguese traditional term (now alternative, but in common use) of the Portuguese Navy.

History

Background

Henry VIII began the English Reformation as a political exercise over his desire to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Over time, it became increasingly aligned with the Protestant reformation taking place in Europe, especially during the reign of Henry's son, Edward VI. Edward died childless and his half-sister, Mary I, ascended the throne. A devout Catholic, Mary, with her co-monarch and husband, Philip II of Spain, began to reassert Roman influence over church affairs. Her attempts led to more than 260 people being burned at the stake, earning her the nickname 'Bloody Mary'.

Philip II of Spain c. 1580, National Portrait Gallery, London

Mary's death in 1558 led to her half-sister, Elizabeth I, taking the throne. Unlike Mary, Elizabeth was firmly in the reformist camp, and quickly reimplemented many of Edward's reforms. Philip, no longer co-monarch, deemed Elizabeth a heretic and illegitimate ruler of England. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, Henry had never officially divorced Catherine, making Elizabeth illegitimate. It is alleged that Phillip supported plots to have Elizabeth overthrown in favour of her Catholic cousin and heir presumptive, Mary, Queen of Scots. These plans were thwarted when Elizabeth had the Queen of Scots imprisoned and executed in 1587. Elizabeth retaliated against Philip by supporting the Dutch revoltagainst Spain, as well as funding privateers to raid Spanish ships across the Atlantic.

In retaliation, Philip planned an expedition to invade England in order to overthrow Elizabeth and, if the Armada was not entirely successful, at least negotiate freedom of worship for Catholics and financial compensation for war in the Low Countries.[30] Through this endeavor, English material support for the United Provinces, the part of the Low Countries that had successfully seceded from Spanish rule, and English attacks on Spanish trade and settlements in the New World would end. The King was supported by Pope Sixtus V, who treated the invasion as a crusade, with the promise of a subsidy should the Armada make land.

A raid on Cádiz, led by Francis Drake in April 1587, had captured or destroyed about 30 ships and great quantities of supplies, setting preparations back by a year. Philip initially favoured a triple attack, starting with a diversionary raid on Scotland, while the main Armada would capture the Isle of Wight, or Southampton, to establish a safe anchorage in the Solent. The Duke of Parma would then follow with a large army from the Low Countries crossing the English Channel. Parma was uneasy about mounting such an invasion without any possibility of surprise. The appointed commander of the Armada was the highly experienced Álvaro de Bazán, Marquis of Santa Cruz, but he died in February 1588, and the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a high-born courtier, took his place. While a competent soldier and distinguished administrator, Medina Sidonia had no naval experience. He wrote to Philip expressing grave doubts about the planned campaign, but his message was prevented from reaching the King by courtiers on the grounds that God would ensure the Armada's success.

Planned invasion of England

See also: List of ships of the Spanish Armada

Route taken by the Spanish Armada

Prior to the undertaking, Pope Sixtus V allowed Philip II of Spain to collect crusade taxes and granted his men indulgences. The blessing of the Armada's banner on 25 April 1588 was similar to the ceremony used prior to the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

On 28 May 1588, the Armada set sail from Lisbon and headed for the English Channel. The fleet was composed of 130 ships, 8,000 sailors and 18,000 soldiers, and bore 1,500 brass guns and 1,000 iron guns. The full body of the fleet took two days to leave port. It included 28 purpose-built warships, of which 20 were galleons, four galleys and four (Neapolitan) galleasses. The remainder of the heavy vessels were mostly armed carracks and hulks together with 34 light ships.

In the Spanish Netherlands, 30,000 soldiers awaited the arrival of the Armada, the plan being to use the cover of the warships to convey the army on barges to a place near London. In all, 55,000 men were to have been mustered, a huge army for that time. On the day the Armada set sail, Elizabeth's ambassador in the Netherlands, Valentine Dale, met Parma's representatives in peace negotiations. The English made a vain effort to intercept the Armada in the Bay of Biscay. On 6 July negotiations were abandoned and the English fleet stood prepared, if ill-supplied, at Plymouth, awaiting news of Spanish movements. The English fleet outnumbered the Spanish, 200 ships to 130,[37] while the Spanish fleet outgunned the English. The Spanish available firepower was 50 percent more than that of the English.[38] The English fleet consisted of the 34 ships of the Royal Fleet, 21 of which were galleons of 200 to 400 tons, and 163 other ships, 30 of which were of 200 to 400 tons and carried up to 42 guns each. Twelve of the ships were privateers owned by Lord Howard of Effingham, Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake.

Signal station built in 1588, above the Devon village of Culmstock, to warn when the Armada was sighted

The Armada was delayed by bad weather. Storms in the Bay of Biscay forced four galleys and one galleon to turn back, and other ships had to put in for repairs, leaving only about 124 ships to actually make it to the English Channel. Nearly half the fleet were not built as warships and were used for duties such as scouting and dispatch work, or for carrying supplies, animals, and troops.

The fleet was sighted in England on 19 July, when it appeared off The Lizard in Cornwall. The news was conveyed to London by a system of beacons that had been constructed all the way along the south coast. On 19 July, the English fleet was trapped in Plymouth Harbour by the incoming tide. The Spanish convened a council of war, where it was proposed to ride into the harbour on the tide and incapacitate the defending ships at anchor. From Plymouth Harbour the Spanish would attack England, but Philip II explicitly forbidden Medina Sidonia to act, leaving the Armada to sail on to the east and toward the Isle of Wight. As the tide turned, 55 English ships set out to confront the Armada from Plymouth under the command of Lord Howard of Effingham, with Sir Francis Drake as Vice Admiral. The rear admiral was Sir John Hawkins.

..... please read about the further process in wikipedia .....

English fireships are launched at the Spanish armada off Calais

List of ships of the Spanish Armada

The armada that attempted to escort an army from Flanders and integrate the Habsburg Spanish invasion of England in 1588, was divided into ten "squadrons" (escuadras) The twenty galleons in the Squadrons of Portugal and of Castile, together with the four galleasses from Naples, constituted the only purpose-built warships (apart from the four galleys, which proved ineffective in the Atlantic waters and soon departed for safety in French ports); the rest of the Armada comprised armed merchantmen (mostly carracks) and various ancillary vessels including urcas (storeships, termed "hulks"), zabras and pataches, pinnaces, and (not included in the formal count) caravels. The division into squadrons was for administrative purposes only; upon sailing, the Armada could not keep to a formal order, and most ships sailed independently from the rest of their squadron.

This list is compiled by a survey drawn up by Medina Sidonia on the Armada's departure from Lisbon on 9 May 1588 and sent to Felipe II; it was then published and quickly became available to the English. The numbers of sailors and soldiers mentioned below are as given in the same survey and thus also relate to this date.

of San José during

of San José during