- Joined

- Jun 17, 2021

- Messages

- 3,205

- Points

- 588

What makes an "extreme clipper" "extreme"?

|

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering. |

|

|

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026! Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue. NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026 |

|

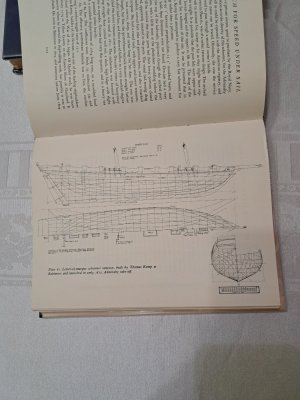

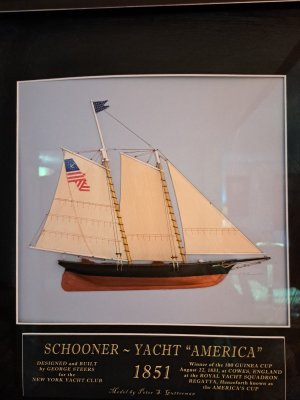

"Madam, there is no second." Although, later scholarship attributes much of "Americas" ' speed to her lightweight cotton sails, which also held a more efficient airfoil, allowing for greater speed close to the wind.

"Madam, there is no second." Although, later scholarship attributes much of "Americas" ' speed to her lightweight cotton sails, which also held a more efficient airfoil, allowing for greater speed close to the wind.

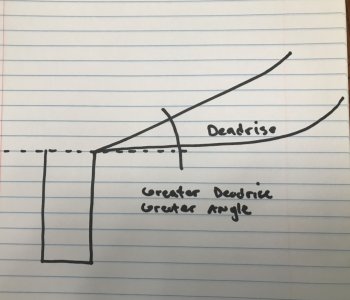

Bill...the *extreme* category has many interpretations...from many sources.Thanks for the replies. I read an article that said because the Flying Cloud only had a 30 inch dead rise, it was not considered a extreme clipper. Also, I read another article that stated to be considered an extreme clipper, a ship had to have a dead rise of at least 40 inches. I’m somewhat confused. My understanding is the dead rise on a ship is the angle between a horizontal line and the keel. ????

Bill

Indeed there is......and since the *Era* lasted only 20 years....much talk has gone into what defined a clipper and those which were extreme and medium.There seem to be a lot of weeds to get lost in in the world of Clippers. (Would those be seaweeds?)

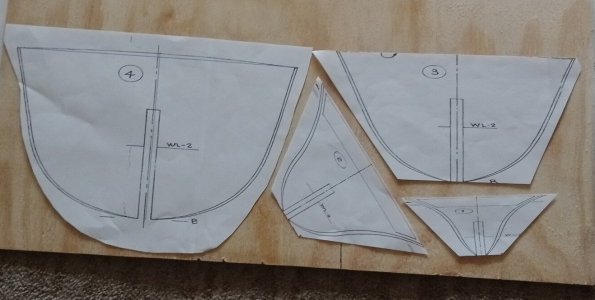

Here is a crude example. The greater the angle of hull the greater the deadrise.Thanks Peter and Rob for the information. I spent some time trying to find a definitive answer to my question about dead rise and the best I could do is get several answers. Sometimes I tend to get focused on something that is more of a point of curiosity and end up spending a lot of time. That's what happens sometimes when you are retired. It does seem interesting that you always find the term dead rise being mentioned around the design of clipper ships, but finding out how it is calculated is difficult. I even broke out one of my marine architecture books from 50 years ago and did not find the answer. I did find one possible answer: 180 - (angle of the hull along a horizontal line from the keel) / 2. It will give you a number, but I still don't know for sure what that number represents. I could speculate on what that number is from other information I got from an internet search, but I think I've gotten too boring already.

Sorry for being long winded.

Bill

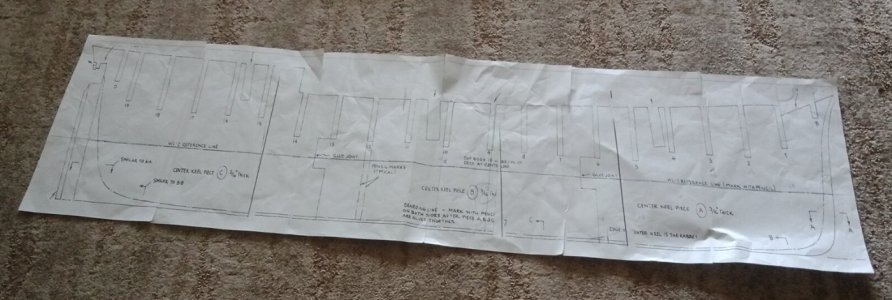

They were purchased from Model Shipways. The first time I've done that. The only thing I had to do is factor all information to the size I wantedHi Clink,

I will be following along with your build. What plans are these or are they your own design.

Bill