Is there any reason the frames cannot be drawn up by tracing the body plan station lines as a starting point?

To be honest, I am not particularly fond of this supposedly fast or easy method. Let me explain:

— Firstly, it is inherently inaccurate, which must be taken into account by adding a large allowance for further processing, and as a result, it takes on more of a carpentry, as opposed to a design or drafting, character (while the latter was the original requirement, for example — for precise laser or CNC cutting).

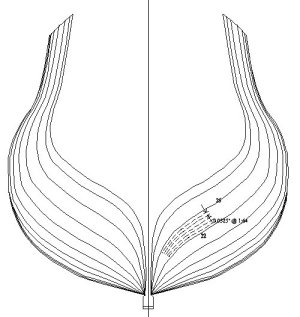

— Secondly, it carries a real and high risk of so-called ‘cow ribs’ forming on the surface of the hull (characteristic of paper models and POBs with too few bulkheads).

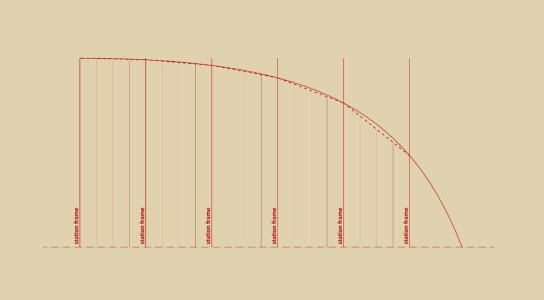

— Thirdly, especially at the extremities of the hull, it is practically impossible for someone without experience in such work to achieve even reasonably approximate contours.

— Fourthly, in general, this rather chaotic method is likely to produce a rather chaotic result, if the whole process can be completed at all without applying orderly procedures.

— Fifthly, this method does not allow for verification of the correctness of the base plans (in particular fairness), which are almost invariably wanting in this respect.

— Sixthly, it may ultimately turn out that the entire effort required by this method will not be less or much less than that required by a methodologically proper method.

.