Part I

The

Battle of the Basque Roads, also known as the

Battle of Aix Roads (

French:

Bataille de l'île d'Aix, also

Affaire des brûlots, rarely

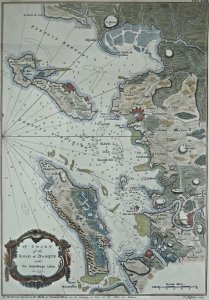

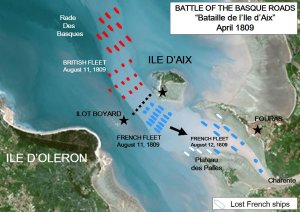

Bataille de la rade des Basques) was a major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars, fought in the narrow Basque Roads at the mouth of the Charente River on the

Biscay coast of

France. The battle, which lasted from

11–25 April 1809, was unusual in that it pitted a hastily-assembled squadron of small and unorthodox British Royal Navy warships against the main strength of the French Atlantic Fleet, the circumstances dictated by the cramped, shallow coastal waters in which the battle was fought. The battle is also notorious for its controversial political aftermath in both Britain and France.

In February 1809 the French Atlantic Fleet,

blockaded in

Brest on the Breton coast by the British Channel Fleet, attempted to break out into the

Atlantic and reinforce the garrison of Martinique. Sighted and chased by British blockade squadrons, the French were unable to escape the Bay of Biscay and eventually anchored in the Basque Roads, near the naval base of Rochefort. There they were kept under observation during March by the British fleet under the dour Admiral Lord Gambier. The Admiralty, desiring an attack on the French fleet, ordered Lord Cochrane, an outspoken and popular junior captain, to lead an attack, over the objections of a number of senior officers. Cochrane organised an inshore squadron of fireships and bomb vessels, including a converted frigate, and personally led this force into Basque Roads on the evening of 11 April.

Destruction of the French Fleet in Basque Roads - April 12th 1809

Destruction of the French Fleet in Basque Roads - April 12th 1809.

The attack caused little direct damage, but in the narrow waters of the channel the fireships panicked the sailors of the French fleet and most of their ships

grounded and were left immobile. Cochrane expected Gambier to follow his attack with the main fleet, which could then destroy the vulnerable French force, but Gambier refused. Cochrane continued the battle over the next several days, successfully destroying several French ships, but with little support from Gambier. This allowed most of the French fleet to refloat and retreat up the Charente to safety. Gambier recalled Cochrane on 14 April and sent him back to Britain, withdrawing most of the inshore squadron at the same time, although scattered fighting continued until 25 April. The increasingly marginalised French fleet was badly damaged and trapped in its home ports; several captains were court-martialed for cowardice and one was

shot.

In Britain the battle was celebrated as a victory, but many in the Navy were dissatisfied with Gambier's behaviour and Cochrane used his position as a

Member of Parliament to publicly protest Gambier's leadership. Incensed, Gambier requested a court-martial to disprove Cochrane's accusations and the admiral's political allies ensured that the jury was composed of his supporters. After bitter and argumentative proceedings Gambier was exonerated of any culpability for failings during the battle. Cochrane's naval career was ruined, although the irrepressible officer remained a prominent figure in Britain for decades to come. Historians have almost unanimously condemned Gambier for his failure to support Cochrane; even Napoleon opined that he was an "

imbécile".

Background

By 1809 the

Royal Navy was dominant in the

Atlantic. During the Trafalgar Campaign of 1805 and the Atlantic Campaign of 1806 the French Atlantic Fleet had suffered severe losses and the survivors were trapped in the French Biscay ports under a close

blockade from the British

Channel Fleet. The largest French base was at

Brest in

Brittany, where the main body of the French fleet lay at anchor under the command of Contre-amiral Jean-Baptiste Willaumez, with smaller French detachments stationed at Lorient and Rochefort. These ports were under observation by the Channel Fleet, led off Brest by Admiral Lord Gambier. Gambier was an unpopular officer, whose reputation rested on being the first captain to break the French line at the Glorious First of June in 1794 in HMS

Defence. Since then he had spent most of his career as an administrator at the

Admiralty, earning the title Baron Gambier for his command of the fleet at the

Bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807. A strict

Methodist, Gambier was nicknamed "Dismal Jimmy" by his men.

Willaumez's cruise

British superiority at sea allowed the Royal Navy to launch operations against the French Overseas Empire with impunity, in particular against the lucrative French colonies in the

Caribbean. In late 1808, the French learned that a British invasion of Martinique was in preparation, and so orders were sent to Willaumez to take his fleet to sea, concentrate with the squadrons from Lorient and Rochefort and reinforce the island. With Gambier's fleet off Ushant Willaumez was powerless to act, and it was only when winter storms forced the blockade fleet to retreat into the Atlantic in February 1809 that the French admiral felt able to put to sea, passing southwards through the Raz de Sein at dawn on 22 February with eight ships of the line and two frigates. Gambier had left a single ship of the line, Captain

Charles Paget's HMS

Revenge to keep watch on Brest, and Paget observed the French movements at 09:00, correctly deducing Willaumez's next destination.

The blockade squadron off Lorient comprised the ships of the line HMS

Theseus, HMS

Triumph and HMS

Valiant under Commodore John Poo Beresford, watching three ships in the harbour under Contre-amiral Amable Troude. At 15:15 Paget, who had lost sight of the French, reached the waters off Lorient and

signaled a warning to Beresford. At 16:30, Beresford's squadron sighted Willaumez's fleet,

tacking to the southeast. Willaumez ordered his second-in-command, Contre-amiral Antoine Louis de Gourdon to drive Beresford away and Gourdoun brought four ships around to chase the British squadron, with the remainder of the French fleet following more distantly. Beresford turned away to the northwest, thus clearing the route to Lorient. His objective achieved, Gourdan rejoined Willaumez and the fleet sailed inshore, anchoring near the island of

Groix.

In the early morning of 23 February, Willaumez sent the dispatch schooner

Magpye into Lorient with instructions for Troude to sail when possible and steer for the

Pertuis d'Antioche near Rochefort, where the fleet was due to assemble. Willaumez then took his fleet southwards, followed from 09:00 by Beresford's squadron. The French fleet passed between Belle Île and Quiberon and then around Île d'Yeu, passing the Phares des Baleines on Île de Ré at 22:30. There the fleet was sighted by frigate

HMS Amethyst under Captain

Michael Seymour, the scout for the Rochefort blockade squadron of HMS

Caesar, HMS

Defiance and HMS

Donegal under Rear-Admiral Robert Stopford, which was anchored off the Phare de Chassiron on

Ile d'Oléron. Signal rockets from

Amethyst alerted Stopford to Willaumez's presence and Stopford closed with Willaumez during the night but was not strong enough to oppose his entry into the

Basque Roads at the mouth of the Charente River on the morning of 24 February.

Gambier's blockade

Assuming that the French fleet had sailed from Brest, Stopford sent the frigate HMS

Naiad under Thomas Dundas to warn Gambier. The British commander had discovered the French fleet missing from its anchorage on 23 February and responded by sending eight ships under Rear-Admiral John Thomas Duckworth south to block any French attempt to enter the Mediterranean while Gambier turned his flagship, the 120-gun first rate HMS

Caledonia, back to Plymouth for reinforcements. In the English Channel

Naiad located

Caledonia and passed on Stopford's message. Gambier continued to Plymouth, collected four ships of the line anchored there, and immediately sailed back into the Bay of Biscay, joining Stopford on 7 March to form a fleet of 13 ships, later reduced to 11 after

Defiance and

Triumph were detached.

Shortly after departing Stopford's squadron off the Basque Roads,

Naiad had sighted three sail approaching from the north at 07:00 on 24 February. These were

Italienne,

Calypso and

Cybèle; a French frigate squadron sent from Lorient by Troude, whose ships of the line had been delayed by unfavourable tides. The lighter frigates had put to sea without the battle squadron and sailed to join Willaumez the previous morning. Their passage had been observed by the British frigate

HMS Amelia and the sloop HMS

Doterel, which had shadowed the French during the night. To the south, Dundas had signaled Stopford and the admiral left

Amethyst and HMS

Emerald to observe the French fleet while he took his main squadron in pursuit of the French frigates. Trapped between the two British forces, French Commodore Pierre-Roch Jurien took his ships inshore under the batteries of Les Sables d'Olonne. Stopford followed the French into the anchorage and in the

ensuing battle drove all three French ships ashore where they were damaged beyond repair.

Willaumez made no move to challenge Stopford or Gambier, although he had successfully united with the Rochefort squadron of three ships of the line, two frigates and an armed storeship, the captured British fourth rate ship

Calcutta, commanded by Commodore Gilbert-Amable Faure. Together the French fleet, now numbering 11 ships of the line, withdrew from the relatively open Basque Roads anchorage into the narrow channel under the batteries of the

Île-d'Aix known as the Aix Roads. These waters offered greater protection from the British fleet, but were also extremely hazardous; on 26 February, as the French manoeuvred into the shallower waters of their new anchorage the 74-gun

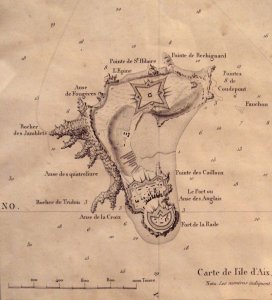

Jean-Bart grounded on the Palles Shoal off Île Madame, and was wrecked. The channel in which Willaumez chose to position his fleet formed a strong defensive position: an assailant had to cross the open Basque Roads and advance past the long and dangerous Boyart Shoal hidden just below the surface. On entering the channel, an attacking force would then come under fire from fortified gun batteries on Île-d'Aix before finally encountering the French fleet. The anchorage had been successfully attacked before, such as during the Raid on Rochefort in 1757, but more recent efforts in 1803, and 1807 had ended in failure.

The developing stalemate saw activity on both sides of the bay. Among the French fleet there was dissatisfaction that Willaumez had not attacked Stopford when he enjoyed numerical superiority, taking the opportunity to break out of the anchorage and pursue his objectives in the Caribbean. Captain Jacques Bergeret was so incensed that he wrote a letter criticising Willaumez to the Minister of Marine Denis Decrès, and warning that the Aix Roads were highly vulnerable to British attack. Although Emperor Napoleon apparently shared Willaumez's opinion, Decrès removed and censured both Willaumez and Bergeret, replacing the admiral with Zacharie Allemand on 16 March. Word had arrived that a British expeditionary force had captured Martinique in late February, and so Allemand, lacking further instructions, prepared his defences.

The French position was strengthened with a heavy

boom formed from chains and tree trunks laid between the Boyart shoal and Île-d'Aix. This boom measured 0.5 nautical miles (1,000 yd) long and 31.5 inches (80 cm) wide, weighted in place with 5 1/4 tons of anchors, and yet was installed so subtly that the British fleet did not observe it. More than 2,000 French conscripts were deployed on the Île-d'Aix, supporting batteries of 36-pounder long guns, although attempts to build a fort on the Boyart Shoal were identified, and on 1 April

Amelia attacked the battery, drove off the construction crew and destroyed the half-finished fortification. Allemand also ordered his captains to take up a position known as a

lignée endentée, in which his ships anchored to form a pair of alternating lines across the channel so that approaching warships could come under the combined fire of several ships at once, in effect crossing the T of any attempt to assault the position, with the frigates stationed between the fleet and the boom.

In the British fleet there was much debate about how to proceed against the French. Gambier was concerned that an attack by French fireships on his fleet anchored in the Basque Roads might cause considerable destruction, and consequently ordered his captains to prepare to withdraw from the blockade at short notice should such an operation be observed. He also wrote to the Admiralty in London recommending British fireships be prepared but cautioning that "it is a horrible mode of warfare, and the attempt very hazardous, if not desperate". A number of officers in the fleet, in particular Rear-Admiral Eliab Harvey, volunteered to lead such an attack, but Gambier hesitated to act, failing to take soundings of the approaches or make any practical preparations for an assault.

Mulgrave's imperative

Lord Cochrane

Lord Cochrane Peter Edward Stroehling, 1807,

GAC

With Gambier vacillating in Basque Roads, First Lord of the Admiralty Lord Mulgrave interceded.

Prime Minister Lord Portland's administration was concerned by the risk posed by the French fleet to the profits of the British colonies in the West Indies, and had determined that an attack must be made. Thus on 7 March ten fireships were ordered to be prepared. In considering who would be best suited to lead such an attack Mulgrave then made a highly controversial decision. On 11 March the frigate HMS

Imperieuse anchored at Plymouth and a message instructed Captain Lord Cochrane to come straight to the Admiralty. Cochrane, eldest son of the Earl of Dundonald, was an aggressive and outspoken officer who had gained notoriety in 1801 when he captured the 32-gun Spanish privateer frigate

Gamo with the 14-gun brig HMS

Speedy. In the frigates HMS

Pallas and

Imperieuse he had caused havoc on the French and Spanish coasts with relentless attacks on coastal shipping and defences including, most relevantly, operations in the Rochefort area. He was also a highly active politician, elected as a Member of Parliament for Westminster in 1807 as a

Radical, he advocated parliamentary reform and was a fierce critic of Portland's administration.

At his meeting with Mulgrave, Cochrane was asked to explain a plan of attack on Basque Roads which he had drawn up some years previously. Cochrane enthusiastically described his intention to use fireships and massive floating bombs to destroy a fleet anchored in the roads. When he had finished, Mulgrave announced that the plan was going ahead and that Cochrane was to command it. Cochrane was in poor health, and under no illusions about Mulgrave's intentions: should the attack fail Cochrane would be blamed and his political career damaged. In addition, Cochrane was also well aware of the fury this decision would provoke in the naval hierarchy; the appointment of a relatively junior officer in command of such an important operation was calculated to cause offense. Cochrane refused, even though Mulgrave pleaded that he had been the only officer to present a practical plan for attacking Allemand's fleet. Again Cochrane refused the command, but the following day Mulgrave issued a direct order: "My Lord you must go. The board cannot listen to further refusal or delay. Rejoin your frigate at once."

Cochrane returned to

Imperieuse immediately and the frigate then sailed from Plymouth to join Gambier. The admiral had received direct orders from Mulgrave on 26 March ordering him to prepare for an attack, to which he sent two letters, one agreeing with the order and another disputing it on the grounds that the water was too shallow and the batteries on Île-d'Aix too dangerous. Gambier did not however learn of the leadership of the operation until Cochrane joined the fleet on 3 April and presented Mulgrave's orders to the admiral. The effect was dramatic; Harvey, one of Nelson's Band of Brothers who had fought at

Trafalgar, launched into a furious tirade directed at Gambier, accusing him of incompetence and malicious conduct, comparing him unfavourably to Nelson and calling Cochrane's appointment an "insult to the fleet". Gambier dismissed Harvey, sending him and his 80-gun HMS

Tonnant back to Britain in disgrace to face a court-martial, and then ordered Cochrane to begin preparations for the attack. Gambier also issued Cochrane with Methodist tracts to distribute to his crew. Cochrane ignored the order, but sent some of the tracts to his friend William Cobbett with a letter describing conditions with the fleet. Cobbett, a Radical journalist, wrote articles in response which later inflamed religious opinion in Britain against Cochrane during the scandal which followed the battle.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Basque_Roads