-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Well, a brass railing would be a huge improvement over brads and thread, for sure. It looks like a nice model that would benefit from the upgrade you're considering. See: https://shipsofscale.com/sosforums/threads/the-juanita-sternwheeler-1-24.16419/page-3#post-440700

If you want the old-fashioned look of the turn of the last century board room models, there's nothing for it but brass. There's a learning curve to it, but well worth taking a shot at learning. It's not rocket science, but there are techniques with which you'll need to become familiar.

Some of the aftermarket parts retailers offer stanchions in various scales. These have round balls on top and halfway up with holes drilled in them through which you run wire to make up railings. That avoids turning your own stanchions, drilling them, and soldering them up.

If you aren't familiar with working with brass and copper detail parts, I suggest you get a copy of Model Building with Brass by Kenneth Foran. It's a great book on the subject. See: https://www.amazon.com/Model-Building-Brass-Kenneth-Foran/dp/0764340042

Also, as a basic how-to book, applicable to jewelry, rather than models, but invaluable for brassworking for models as well, you may want to check out Metalworker's Workbench: Demystifying the Jeweler's Saw, by Thomas Mann. See: https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/Bo...-naa&msclkid=3d607abb760a1209814512c46dacf1d0

If you want the old-fashioned look of the turn of the last century board room models, there's nothing for it but brass. There's a learning curve to it, but well worth taking a shot at learning. It's not rocket science, but there are techniques with which you'll need to become familiar.

Some of the aftermarket parts retailers offer stanchions in various scales. These have round balls on top and halfway up with holes drilled in them through which you run wire to make up railings. That avoids turning your own stanchions, drilling them, and soldering them up.

If you aren't familiar with working with brass and copper detail parts, I suggest you get a copy of Model Building with Brass by Kenneth Foran. It's a great book on the subject. See: https://www.amazon.com/Model-Building-Brass-Kenneth-Foran/dp/0764340042

Also, as a basic how-to book, applicable to jewelry, rather than models, but invaluable for brassworking for models as well, you may want to check out Metalworker's Workbench: Demystifying the Jeweler's Saw, by Thomas Mann. See: https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/Bo...-naa&msclkid=3d607abb760a1209814512c46dacf1d0

Another option that would not be quite as classy as turned stanchions, but would be cheaper to do, is brass pins for stanchions, notched with a jeweler’s file or rotary tool where the rails meet them. Fine brass wire for the rails is then soldered to the notches. By using soldering paste instead of wire solder, you can really control how much solder is used and avoid unsightly blobs.

Thanks Bob. I have thought about that. your railing is very beatifull. But is a modern ship beleive 1925 or so. Mine is a 837 paddel steamer. there are no blueprints or so. only historical paintings. those show a lot of differences. Railings where made in that era of Wrought iron .I made your kind of railings for modelrailroad in HO.Well, a brass railing would be a huge improvement over brads and thread, for sure. It looks like a nice model that would benefit from the upgrade you're considering. See: https://shipsofscale.com/sosforums/threads/the-juanita-sternwheeler-1-24.16419/page-3#post-440700

If you want the old-fashioned look of the turn of the last century board room models, there's nothing for it but brass. There's a learning curve to it, but well worth taking a shot at learning. It's not rocket science, but there are techniques with which you'll need to become familiar.

Some of the aftermarket parts retailers offer stanchions in various scales. These have round balls on top and halfway up with holes drilled in them through which you run wire to make up railings. That avoids turning your own stanchions, drilling them, and soldering them up.

If you aren't familiar with working with brass and copper detail parts, I suggest you get a copy of Model Building with Brass by Kenneth Foran. It's a great book on the subject. See: https://www.amazon.com/Model-Building-Brass-Kenneth-Foran/dp/0764340042

Also, as a basic how-to book, applicable to jewelry, rather than models, but invaluable for brassworking for models as well, you may want to check out Metalworker's Workbench: Demystifying the Jeweler's Saw, by Thomas Mann. See: https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/Bo...-naa&msclkid=3d607abb760a1209814512c46dacf1d0

I like youre idea. especialy for the 1837 build ship looks more like it is forged from wrought iron. am thinking about replacing the nails for headless.Another option that would not be quite as classy as turned stanchions, but would be cheaper to do, is brass pins for stanchions, notched with a jeweler’s file or rotary tool where the rails meet them. Fine brass wire for the rails is then soldered to the notches. By using soldering paste instead of wire solder, you can really control how much solder is used and avoid unsightly blobs.

Thanks Bob. I have thought about that. your railing is very beatifull. But is a modern ship beleive 1925 or so. Mine is a 837 paddel steamer. there are no blueprints or so. only historical paintings. those show a lot of differences. Railings where made in that era of Wrought iron .I made your kind of railings for modelrailroad in HO.

I thought you were finishing the wood "bright" and going with brass. If you want an iron railing, "blacken" or paint the brass railing to suit your taste.

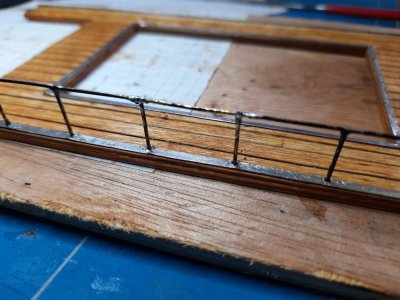

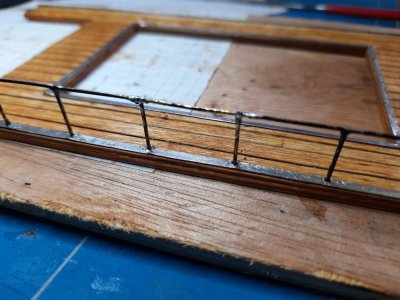

Hi, after quite some studying and trying came to the conclusion that i needed to raise the paddle boxxes in order to better resemble the original drawing of the Sirius. so had to make new walkway as wel. also by using a 0.85 mm brass wire 1:60 scale would have been right size for railing and stanchions. so went ahead and soldered the brass wire to stanchions. for bottom plank i used file hanger paper and glued copper tape on top then applied some solder. this makes it extra stiff. everything needs to be painted Stained and some solder cleaned up. Final assembly wil be done after i finish all the rigging so i have enough acces.sure looks a lot better than the nails and rope i used before. any suggestions comments welcome

Nice job! looks good. Years ago I tried to do metal railings , just couldn't get the soldering right.Hi, after quite some studying and trying came to the conclusion that i needed to raise the paddle boxxes in order to better resemble the original drawing of the Sirius. so had to make new walkway as wel. also by using a 0.85 mm brass wire 1:60 scale would have been right size for railing and stanchions. so went ahead and soldered the brass wire to stanchions. for bottom plank i used file hanger paper and glued copper tape on top then applied some solder. this makes it extra stiff. everything needs to be painted Stained and some solder cleaned up. Final assembly wil be done after i finish all the rigging so i have enough acces.sure looks a lot better than the nails and rope i used before. any suggestions comments welcome

View attachment 537349

View attachment 537350

View attachment 537351

View attachment 537352

View attachment 537353

Great job ! Nice, even and consistent

If you can import them, Ages Of Sail in California has a large selection of brass stanchions of great quality. I used piano wire for the railings..Amati and caldercraft also great. Used a lot for my OKESA.

- Joined

- Jun 29, 2024

- Messages

- 1,520

- Points

- 438

Tinned brass wire (wire coated with a fine even coat of solder) is available in various diameters. I have some that is only .010”. I have not yet used it to make metal railings but intend to do so.

Amazon lists this but their source is Remington Industries in Illinois.

Roger

Amazon lists this but their source is Remington Industries in Illinois.

Roger

You've definitely got the hang of it now! It's looking much better than before.

Since you've asked for recommendations, and since ship modeling is essentially an exercise in the pursuit of unattainable perfection ( ,) I suggest for your consideration the following:

,) I suggest for your consideration the following:

You can straighten malleable wire, especially short pieces, by rolling them between two flat plates of heavy hard material. Hardwood, if nothing else, but better if you use metal or thick plate glass. Anything you have around the shop will work. When I can't find any thing better close at hand, I use the sole of a heavy iron plane (with the blade retracted!) and the top of my table saw. I lay the piece of wire on the table saw and, placing the plane sole on top of it, roll the wire between the two flat iron surfaces by pushing the plane back and forth while applying downward pressure with the plane. The wire is thus straightened perfectly as it is forced to roll back and forth between the two flat iron surfaces. If you don't have a plane or a table saw, you could even use a couple of flat-bottomed frying pans from the "cook's galley" placed back to back when she isn't looking!

If you are working with yellow metal (brass or copper,) and you find the wire is too stiff to work with easily, it can be annealed (made soft) by heating with a torch until it is red hot and then allowed to cool slowly. (I.e., Let it cool on its own, not by quenching in water.) This will take the hardness ("spring") out of it and it will bend easily and stay bent where you want it to.

Soldering goes much more smoothly where:

(1) The surfaces to be joined are perfectly clean. This means either sanded with fine abrasive to bright, bare surface, or cleaned carefully with acetone or at least vinegar (acetic acid.) (There are other "pickling" concoctions on the market, but these cost money and I always hesitate to spend money on such things when I can replicate the desired effect with something generic from my shop stores or the kitchen cabinet.) Surface cleanliness is essential.

(2) If possible, avoid using rosin core solder electrical solder. This is a soft solder in wire form that contains flux in the solder wire. Solder will only adhere where the flux is present on the metal to be joined. Rosin core solder is made to flow anywhere there is metal, as in joining electrical connections. Modeling demands much more precise control of the solder flow to prevent too much solder on the joint running far beyond where you want it to be, occasioning a lot of subsequent filing to clean up the excess solder. Two approaches can be used to avoid this. (A) use paste form silver solder. This is a gray "grease" made of fine silver solder powder mixed in a greasy flux. It's applied by brushing a bit of it precisely where you want the solder joint to occur. A tiny dab will do it. Then apply heat. Note that when using silver solder, the metal parts to be joined must be in contact with each other. (A diagonal wire cutter will leave a chisel edged end to the cut wire which will not join well; file the ends flat. Silver solder is not "gap filling." Filing the faying surfaces of the desired joint flat for good contact is required, but silver solder is much stronger than soft solder, so only a very small amount of contact surface is required. (B) Separate flux paste can be used, which allows brushing the flux onto the surface where you want the solder to flow. No flux on the surface, no solder will flow onto and adhere to it. This makes it possible to apply solder precisely without later having to clean up excess blobs of solder on your joints. When using flux paste, use solder without flux incorporated into it.

(3) Control the amount of solder to be applied to a joint by applying solid bits of solder to the joint and then applying heat. Applying solder by heating a solder in wire form directly from the coil at the joint doesn't permit you to control the amount of solder that's being applied and will cause a messy "blob" that you'll have to file down. Most solder comes in coiled wire form and the wire is often thicker and harder than to be suitable for cutting very small bits from the wire. The solution is to put the end of the wire on the spool onto your anvil and hammer the end of the solder wire flat and paper thin. Very small bits of solder, called "pallions" by jewelers, can then be snipped off the flattened solder wire end with your small diagonal cutters. (Make a sufficient number and store them in a small container so you don't have to interrupt your soldering session to cut them one at a time.) Using a fine pointed tweezers (or a fine pointed paintbrush moistened with a bit of flux) these tiny pallions are picked up and applied to (or with) the flux right at the contact joint of the pieces to be soldered. Heat is then applied, which liquifies the flux and then, at its higher melting temperature, the solder, which should run into the joint. Remember, if you are using silver solder, it will only form a joint where the parts are actually touching each other, so they have to be filed flat to make as much physical contact as possible. If you are using soft solder (tin and lead, etc., not silver) the process is the same, but silver solder produces a much stronger bond.

(4) When a number of joints must be soldered on a single small piece, it is sometimes the case that an adjacent previously soldered joint will liquify from the heat of the adjacent next one, which can be maddingly frustrating. In such instance, a heat sink should cure the problem. A heat sink is just something to draw the heat from the workpiece so as to insulate the previous joint from the next one. Commonly, a metal hemostat or other clamp, or two, will be sufficient. Some use a chunk of cold raw potato or apple to good effect. (And some have been known to squirt liquid nitrogen on the previous joints, but that's a bit above my pay grade.) If a heat sink doesn't work, there are also a range of solders available distinguished by their different melting points: low, medium, and high heat. The first joints are soldered with the highest temperature solder and you work your way down from there. You can still melt a previous joint using different melting points if you don't move fast enough doing the subsequent joints, but at least the temperature differences give you a running head start. (There is a third approach to this problem called "resistance soldering." This method involves running a high-amperage electrical current through the parts to be joined, causing the resistance of the joint to cause the joint to heat sufficiently to melt solder. The equipment is expensive and while I am familiar with the technique, I am not experienced with it, so I'll leave its story for another night.)

(5) I've found modeling soldering far easier using a jeweler's torch than a soldering iron or gun. A torch is easier to direct high heat to a smaller point than an iron or gun, which require heating a much larger area of the parts to be joined. A torch is much hotter and the torch's temperature can be adjusted easily by adjusting its flame and the distance the flame is held from the joint. Also, a torch permits applying heat without touching the parts to be joined, which can be a big issue because a joint that moves while cooling, called a "cold joint," recognizable because it is dull and not shiny when cooled (and which also often isn't visible when a joint is hidden by the pieces,) is very weak and liable to break. There are many models of jeweler's torches available from jewelry supply houses. One of the most popular for modeling purposes is the Smith Little Torch. This high-quality U.S.A.-made jeweler's torch will burn oxy/propane, oxy/mapp, and oxy/acetelene mixtures. The Smith Little Torch is sold separately, or in a kit which includes the torch and necessary gas regulators and the full kit will run you about $275.00 USD from Amazon. [See: https://www.amazon.com/Smith-Little-Torch-Soldering-Welding/dp/B000T43L30] That said, if you dare, there is an identically-appearing "Little Torch" made by the Patriotic Revolutionary Chinese People's Jeweler's Torch-Making Collective that sells for a third the price or less. [See: https://www.amazon.com/AeKeatDa-Soldering-Welding-Construction-Hobbyists/dp/B08XGJGP7B/ref=sr_1_1_sspa?adgrpid=1334808847558900&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.CQ13byqyP58mIPw1XRjv0jE8Iceiye-lzDORcNMCtZmeDZJbG7CI5iXoAvWXWdY6hwP5OE-wCFJx4zTghPek2KIA6SmDsxv5mdahLh6aIFdB9fAgAmgc3YORV9R-rm5zYDM6hxfOZ7yMpTBYHB1JNNjkqnBXugF1OhqxD3LZQmHQxYzvJNkNfAGICMWyPx8l13zFjYLrXVMyRShjKR37LPocorU2RtlFPXIuMRVRmlGAo2NU7wy5s--t9u7hCcP8Qxrq39G_1phk96HpjtjCoAH5-ECiZfRclDWHdQys7Ls.1IHrSO59BieaFwX9hr5Z0-qsYqEwVl9dYKUJAKMydVU&dib_tag=se&hvadid=83425841660837&hvbmt=be&hvdev=c&hvlocphy=88716&hvnetw=o&hvqmt=e&hvtargid=kwd-83426611059650:loc-190&hydadcr=1608_13458094&keywords=little+torch&mcid=c2a2e441071730048dc689a6df1b966e&msclkid=3dc77e191c6118f0b8b2168341b8227c&qid=1754947040&s=hi&sr=1-1-spons&sp_csd=d2lkZ2V0TmFtZT1zcF9hdGY&psc=1] I bought one, thinking they were the same, but they are not the same by a long shot! They look identical, but the Chinese knock off is made of inferior material and the critical machining of the tips is reportedly quite variable. The one I bought had a serious leak in the oxy hose due to a faulty hose clamp. I hate to admit it, but took me some time to test for the obvious: a leak in the supply hose. I just assumed that wasn't a defect any manufacturer would allow to leave their factory. (I've learned a lot about doing business with Chinese manufacturers since.) The price of the American original is probably steep for many beginning modelers, but while there are lots of less expensive alternatives, it's been my experience that a soldering rig is one of those tools that one is better off buying the best they can afford. Those will last a lifetime and hold a solid resale value if you ever want to get rid of them. My knock off works great now that I've gone over it with a fine toothed comb, but I would never have bought it had I realized at the time that it was not the "little torch" everybody recommended. If you get one, make sure it is a Made in USA Smith's Little Torch and save yourself the worry about an accident caused by Chinese export quality control.

(6.) Treat yourself to a Quadhands soldering stand. These clever "helping hands" tools are made for holding parts like printed circuit boards for soldering in the high-tech industry. Get one and you'll never use your classic "helping hands" stand with the ball joints tightened with the perpetually loosening wingnuts for anything other than a paperweight. I would put this in my list of essential ship modeling tools. Not only is it infinitely adjustable with its arms set anywhere on the heavy metal base courtesy of rare earth magnets, but its strong bendable arms and alligator clip ends will firmly hold not only multiple parts for soldering but also are really handy for all sorts of rigging chores like stropping and whipping blocks and holding spars for rigging off their mast. Unfortunately, like the Little Torch mentioned above, the internet is full of identically appearing Far Eastern Quadhands knock-offs made by twelve-year-olds chained to their workbenches. As usual, the quality of the counterfeits is below that of the real McCoy. Quadhands come in a variety of sizes and configurations and additional arms can be purchased separately. Prices are very reasonable. Accept no substitutes! (See: https://www.quadhands.com/)

With soldering, as most things, practice makes perfect. The more you practice, the better, and faster, you'll get. It's entirely possible to solder near invisible joints with a bit of practice and care. Don't be intimidated. Once you've got it down, you'll probably find yourself replacing a lot of kit-provided white metal castings with scratch-built brass and copper parts!

A good book on model soldering to have on your research library shelf is Model Building with Brass by Kenneth Foran. (See: https://www.amazon.com/Model-Building-Brass-Kenneth-Foran/dp/0764340042 )

Since you've asked for recommendations, and since ship modeling is essentially an exercise in the pursuit of unattainable perfection (

You can straighten malleable wire, especially short pieces, by rolling them between two flat plates of heavy hard material. Hardwood, if nothing else, but better if you use metal or thick plate glass. Anything you have around the shop will work. When I can't find any thing better close at hand, I use the sole of a heavy iron plane (with the blade retracted!) and the top of my table saw. I lay the piece of wire on the table saw and, placing the plane sole on top of it, roll the wire between the two flat iron surfaces by pushing the plane back and forth while applying downward pressure with the plane. The wire is thus straightened perfectly as it is forced to roll back and forth between the two flat iron surfaces. If you don't have a plane or a table saw, you could even use a couple of flat-bottomed frying pans from the "cook's galley" placed back to back when she isn't looking!

If you are working with yellow metal (brass or copper,) and you find the wire is too stiff to work with easily, it can be annealed (made soft) by heating with a torch until it is red hot and then allowed to cool slowly. (I.e., Let it cool on its own, not by quenching in water.) This will take the hardness ("spring") out of it and it will bend easily and stay bent where you want it to.

Soldering goes much more smoothly where:

(1) The surfaces to be joined are perfectly clean. This means either sanded with fine abrasive to bright, bare surface, or cleaned carefully with acetone or at least vinegar (acetic acid.) (There are other "pickling" concoctions on the market, but these cost money and I always hesitate to spend money on such things when I can replicate the desired effect with something generic from my shop stores or the kitchen cabinet.) Surface cleanliness is essential.

(2) If possible, avoid using rosin core solder electrical solder. This is a soft solder in wire form that contains flux in the solder wire. Solder will only adhere where the flux is present on the metal to be joined. Rosin core solder is made to flow anywhere there is metal, as in joining electrical connections. Modeling demands much more precise control of the solder flow to prevent too much solder on the joint running far beyond where you want it to be, occasioning a lot of subsequent filing to clean up the excess solder. Two approaches can be used to avoid this. (A) use paste form silver solder. This is a gray "grease" made of fine silver solder powder mixed in a greasy flux. It's applied by brushing a bit of it precisely where you want the solder joint to occur. A tiny dab will do it. Then apply heat. Note that when using silver solder, the metal parts to be joined must be in contact with each other. (A diagonal wire cutter will leave a chisel edged end to the cut wire which will not join well; file the ends flat. Silver solder is not "gap filling." Filing the faying surfaces of the desired joint flat for good contact is required, but silver solder is much stronger than soft solder, so only a very small amount of contact surface is required. (B) Separate flux paste can be used, which allows brushing the flux onto the surface where you want the solder to flow. No flux on the surface, no solder will flow onto and adhere to it. This makes it possible to apply solder precisely without later having to clean up excess blobs of solder on your joints. When using flux paste, use solder without flux incorporated into it.

(3) Control the amount of solder to be applied to a joint by applying solid bits of solder to the joint and then applying heat. Applying solder by heating a solder in wire form directly from the coil at the joint doesn't permit you to control the amount of solder that's being applied and will cause a messy "blob" that you'll have to file down. Most solder comes in coiled wire form and the wire is often thicker and harder than to be suitable for cutting very small bits from the wire. The solution is to put the end of the wire on the spool onto your anvil and hammer the end of the solder wire flat and paper thin. Very small bits of solder, called "pallions" by jewelers, can then be snipped off the flattened solder wire end with your small diagonal cutters. (Make a sufficient number and store them in a small container so you don't have to interrupt your soldering session to cut them one at a time.) Using a fine pointed tweezers (or a fine pointed paintbrush moistened with a bit of flux) these tiny pallions are picked up and applied to (or with) the flux right at the contact joint of the pieces to be soldered. Heat is then applied, which liquifies the flux and then, at its higher melting temperature, the solder, which should run into the joint. Remember, if you are using silver solder, it will only form a joint where the parts are actually touching each other, so they have to be filed flat to make as much physical contact as possible. If you are using soft solder (tin and lead, etc., not silver) the process is the same, but silver solder produces a much stronger bond.

(4) When a number of joints must be soldered on a single small piece, it is sometimes the case that an adjacent previously soldered joint will liquify from the heat of the adjacent next one, which can be maddingly frustrating. In such instance, a heat sink should cure the problem. A heat sink is just something to draw the heat from the workpiece so as to insulate the previous joint from the next one. Commonly, a metal hemostat or other clamp, or two, will be sufficient. Some use a chunk of cold raw potato or apple to good effect. (And some have been known to squirt liquid nitrogen on the previous joints, but that's a bit above my pay grade.) If a heat sink doesn't work, there are also a range of solders available distinguished by their different melting points: low, medium, and high heat. The first joints are soldered with the highest temperature solder and you work your way down from there. You can still melt a previous joint using different melting points if you don't move fast enough doing the subsequent joints, but at least the temperature differences give you a running head start. (There is a third approach to this problem called "resistance soldering." This method involves running a high-amperage electrical current through the parts to be joined, causing the resistance of the joint to cause the joint to heat sufficiently to melt solder. The equipment is expensive and while I am familiar with the technique, I am not experienced with it, so I'll leave its story for another night.)

(5) I've found modeling soldering far easier using a jeweler's torch than a soldering iron or gun. A torch is easier to direct high heat to a smaller point than an iron or gun, which require heating a much larger area of the parts to be joined. A torch is much hotter and the torch's temperature can be adjusted easily by adjusting its flame and the distance the flame is held from the joint. Also, a torch permits applying heat without touching the parts to be joined, which can be a big issue because a joint that moves while cooling, called a "cold joint," recognizable because it is dull and not shiny when cooled (and which also often isn't visible when a joint is hidden by the pieces,) is very weak and liable to break. There are many models of jeweler's torches available from jewelry supply houses. One of the most popular for modeling purposes is the Smith Little Torch. This high-quality U.S.A.-made jeweler's torch will burn oxy/propane, oxy/mapp, and oxy/acetelene mixtures. The Smith Little Torch is sold separately, or in a kit which includes the torch and necessary gas regulators and the full kit will run you about $275.00 USD from Amazon. [See: https://www.amazon.com/Smith-Little-Torch-Soldering-Welding/dp/B000T43L30] That said, if you dare, there is an identically-appearing "Little Torch" made by the Patriotic Revolutionary Chinese People's Jeweler's Torch-Making Collective that sells for a third the price or less. [See: https://www.amazon.com/AeKeatDa-Soldering-Welding-Construction-Hobbyists/dp/B08XGJGP7B/ref=sr_1_1_sspa?adgrpid=1334808847558900&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.CQ13byqyP58mIPw1XRjv0jE8Iceiye-lzDORcNMCtZmeDZJbG7CI5iXoAvWXWdY6hwP5OE-wCFJx4zTghPek2KIA6SmDsxv5mdahLh6aIFdB9fAgAmgc3YORV9R-rm5zYDM6hxfOZ7yMpTBYHB1JNNjkqnBXugF1OhqxD3LZQmHQxYzvJNkNfAGICMWyPx8l13zFjYLrXVMyRShjKR37LPocorU2RtlFPXIuMRVRmlGAo2NU7wy5s--t9u7hCcP8Qxrq39G_1phk96HpjtjCoAH5-ECiZfRclDWHdQys7Ls.1IHrSO59BieaFwX9hr5Z0-qsYqEwVl9dYKUJAKMydVU&dib_tag=se&hvadid=83425841660837&hvbmt=be&hvdev=c&hvlocphy=88716&hvnetw=o&hvqmt=e&hvtargid=kwd-83426611059650:loc-190&hydadcr=1608_13458094&keywords=little+torch&mcid=c2a2e441071730048dc689a6df1b966e&msclkid=3dc77e191c6118f0b8b2168341b8227c&qid=1754947040&s=hi&sr=1-1-spons&sp_csd=d2lkZ2V0TmFtZT1zcF9hdGY&psc=1] I bought one, thinking they were the same, but they are not the same by a long shot! They look identical, but the Chinese knock off is made of inferior material and the critical machining of the tips is reportedly quite variable. The one I bought had a serious leak in the oxy hose due to a faulty hose clamp. I hate to admit it, but took me some time to test for the obvious: a leak in the supply hose. I just assumed that wasn't a defect any manufacturer would allow to leave their factory. (I've learned a lot about doing business with Chinese manufacturers since.) The price of the American original is probably steep for many beginning modelers, but while there are lots of less expensive alternatives, it's been my experience that a soldering rig is one of those tools that one is better off buying the best they can afford. Those will last a lifetime and hold a solid resale value if you ever want to get rid of them. My knock off works great now that I've gone over it with a fine toothed comb, but I would never have bought it had I realized at the time that it was not the "little torch" everybody recommended. If you get one, make sure it is a Made in USA Smith's Little Torch and save yourself the worry about an accident caused by Chinese export quality control.

(6.) Treat yourself to a Quadhands soldering stand. These clever "helping hands" tools are made for holding parts like printed circuit boards for soldering in the high-tech industry. Get one and you'll never use your classic "helping hands" stand with the ball joints tightened with the perpetually loosening wingnuts for anything other than a paperweight. I would put this in my list of essential ship modeling tools. Not only is it infinitely adjustable with its arms set anywhere on the heavy metal base courtesy of rare earth magnets, but its strong bendable arms and alligator clip ends will firmly hold not only multiple parts for soldering but also are really handy for all sorts of rigging chores like stropping and whipping blocks and holding spars for rigging off their mast. Unfortunately, like the Little Torch mentioned above, the internet is full of identically appearing Far Eastern Quadhands knock-offs made by twelve-year-olds chained to their workbenches. As usual, the quality of the counterfeits is below that of the real McCoy. Quadhands come in a variety of sizes and configurations and additional arms can be purchased separately. Prices are very reasonable. Accept no substitutes! (See: https://www.quadhands.com/)

With soldering, as most things, practice makes perfect. The more you practice, the better, and faster, you'll get. It's entirely possible to solder near invisible joints with a bit of practice and care. Don't be intimidated. Once you've got it down, you'll probably find yourself replacing a lot of kit-provided white metal castings with scratch-built brass and copper parts!

A good book on model soldering to have on your research library shelf is Model Building with Brass by Kenneth Foran. (See: https://www.amazon.com/Model-Building-Brass-Kenneth-Foran/dp/0764340042 )

I live in Aruba no modelshops. If I order from USA Shipping to Aruba (if they do. most do not) has at least a40$ shippingcharge plus customs etc. If i have freinds traveling to Holland i try to order things there so they can just bring it back in their bags.If you can import them, Ages Of Sail in California has a large selection of brass stanchions of great quality. I used piano wire for the railings..Amati and caldercraft also great. Used a lot for my OKESA.

Thanks for your expert advice, most of the tools you mentioned are not available here in Aruba. So i go with what i have. I use the oatay nr 95 flux with thin and a high quality solder thin used for electronics. main problem was that my tip of the soldering iron was in bad shape and was getting too hot. sed the 35watt iron. last ones i did where with the 25 watt iron and that made uge difference.. I used the bright collored brass wire. straightened it in vise with drill on other end this makes it straiht and much stiffer. firt part of railing i did on pice of paper but the pieses kept moving. So rest i drillied the holes first in walkway. then inserted stanchions straightened it with metal ruler. then soldered 1st and last pin then rest. so far so good only need to go over the whole thing to remove exxes solder and straingthen some pins here and ther.You've definitely got the hang of it now! It's looking much better than before.

Since you've asked for recommendations, and since ship modeling is essentially an exercise in the pursuit of unattainable perfection (,) I suggest for your consideration the following:

You can straighten malleable wire, especially short pieces, by rolling them between two flat plates of heavy hard material. Hardwood, if nothing else, but better if you use metal or thick plate glass. Anything you have around the shop will work. When I can't find any thing better close at hand, I use the sole of a heavy iron plane (with the blade retracted!) and the top of my table saw. I lay the piece of wire on the table saw and, placing the plane sole on top of it, roll the wire between the two flat iron surfaces by pushing the plane back and forth while applying downward pressure with the plane. The wire is thus straightened perfectly as it is forced to roll back and forth between the two flat iron surfaces. If you don't have a plane or a table saw, you could even use a couple of flat-bottomed frying pans from the "cook's galley" placed back to back when she isn't looking!

If you are working with yellow metal (brass or copper,) and you find the wire is too stiff to work with easily, it can be annealed (made soft) by heating with a torch until it is red hot and then allowed to cool slowly. (I.e., Let it cool on its own, not by quenching in water.) This will take the hardness ("spring") out of it and it will bend easily and stay bent where you want it to.

Soldering goes much more smoothly where:

(1) The surfaces to be joined are perfectly clean. This means either sanded with fine abrasive to bright, bare surface, or cleaned carefully with acetone or at least vinegar (acetic acid.) (There are other "pickling" concoctions on the market, but these cost money and I always hesitate to spend money on such things when I can replicate the desired effect with something generic from my shop stores or the kitchen cabinet.) Surface cleanliness is essential.

(2) If possible, avoid using rosin core solder electrical solder. This is a soft solder in wire form that contains flux in the solder wire. Solder will only adhere where the flux is present on the metal to be joined. Rosin core solder is made to flow anywhere there is metal, as in joining electrical connections. Modeling demands much more precise control of the solder flow to prevent too much solder on the joint running far beyond where you want it to be, occasioning a lot of subsequent filing to clean up the excess solder. Two approaches can be used to avoid this. (A) use paste form silver solder. This is a gray "grease" made of fine silver solder powder mixed in a greasy flux. It's applied by brushing a bit of it precisely where you want the solder joint to occur. A tiny dab will do it. Then apply heat. Note that when using silver solder, the metal parts to be joined must be in contact with each other. (A diagonal wire cutter will leave a chisel edged end to the cut wire which will not join well; file the ends flat. Silver solder is not "gap filling." Filing the faying surfaces of the desired joint flat for good contact is required, but silver solder is much stronger than soft solder, so only a very small amount of contact surface is required. (B) Separate flux paste can be used, which allows brushing the flux onto the surface where you want the solder to flow. No flux on the surface, no solder will flow onto and adhere to it. This makes it possible to apply solder precisely without later having to clean up excess blobs of solder on your joints. When using flux paste, use solder without flux incorporated into it.

(3) Control the amount of solder to be applied to a joint by applying solid bits of solder to the joint and then applying heat. Applying solder by heating a solder in wire form directly from the coil at the joint doesn't permit you to control the amount of solder that's being applied and will cause a messy "blob" that you'll have to file down. Most solder comes in coiled wire form and the wire is often thicker and harder than to be suitable for cutting very small bits from the wire. The solution is to put the end of the wire on the spool onto your anvil and hammer the end of the solder wire flat and paper thin. Very small bits of solder, called "pallions" by jewelers, can then be snipped off the flattened solder wire end with your small diagonal cutters. (Make a sufficient number and store them in a small container so you don't have to interrupt your soldering session to cut them one at a time.) Using a fine pointed tweezers (or a fine pointed paintbrush moistened with a bit of flux) these tiny pallions are picked up and applied to (or with) the flux right at the contact joint of the pieces to be soldered. Heat is then applied, which liquifies the flux and then, at its higher melting temperature, the solder, which should run into the joint. Remember, if you are using silver solder, it will only form a joint where the parts are actually touching each other, so they have to be filed flat to make as much physical contact as possible. If you are using soft solder (tin and lead, etc., not silver) the process is the same, but silver solder produces a much stronger bond.

(4) When a number of joints must be soldered on a single small piece, it is sometimes the case that an adjacent previously soldered joint will liquify from the heat of the adjacent next one, which can be maddingly frustrating. In such instance, a heat sink should cure the problem. A heat sink is just something to draw the heat from the workpiece so as to insulate the previous joint from the next one. Commonly, a metal hemostat or other clamp, or two, will be sufficient. Some use a chunk of cold raw potato or apple to good effect. (And some have been known to squirt liquid nitrogen on the previous joints, but that's a bit above my pay grade.) If a heat sink doesn't work, there are also a range of solders available distinguished by their different melting points: low, medium, and high heat. The first joints are soldered with the highest temperature solder and you work your way down from there. You can still melt a previous joint using different melting points if you don't move fast enough doing the subsequent joints, but at least the temperature differences give you a running head start. (There is a third approach to this problem called "resistance soldering." This method involves running a high-amperage electrical current through the parts to be joined, causing the resistance of the joint to cause the joint to heat sufficiently to melt solder. The equipment is expensive and while I am familiar with the technique, I am not experienced with it, so I'll leave its story for another night.)

(5) I've found modeling soldering far easier using a jeweler's torch than a soldering iron or gun. A torch is easier to direct high heat to a smaller point than an iron or gun, which require heating a much larger area of the parts to be joined. A torch is much hotter and the torch's temperature can be adjusted easily by adjusting its flame and the distance the flame is held from the joint. Also, a torch permits applying heat without touching the parts to be joined, which can be a big issue because a joint that moves while cooling, called a "cold joint," recognizable because it is dull and not shiny when cooled (and which also often isn't visible when a joint is hidden by the pieces,) is very weak and liable to break. There are many models of jeweler's torches available from jewelry supply houses. One of the most popular for modeling purposes is the Smith Little Torch. This high-quality U.S.A.-made jeweler's torch will burn oxy/propane, oxy/mapp, and oxy/acetelene mixtures. The Smith Little Torch is sold separately, or in a kit which includes the torch and necessary gas regulators and the full kit will run you about $275.00 USD from Amazon. [See: https://www.amazon.com/Smith-Little-Torch-Soldering-Welding/dp/B000T43L30] That said, if you dare, there is an identically-appearing "Little Torch" made by the Patriotic Revolutionary Chinese People's Jeweler's Torch-Making Collective that sells for a third the price or less. [See: https://www.amazon.com/AeKeatDa-Soldering-Welding-Construction-Hobbyists/dp/B08XGJGP7B/ref=sr_1_1_sspa?adgrpid=1334808847558900&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.CQ13byqyP58mIPw1XRjv0jE8Iceiye-lzDORcNMCtZmeDZJbG7CI5iXoAvWXWdY6hwP5OE-wCFJx4zTghPek2KIA6SmDsxv5mdahLh6aIFdB9fAgAmgc3YORV9R-rm5zYDM6hxfOZ7yMpTBYHB1JNNjkqnBXugF1OhqxD3LZQmHQxYzvJNkNfAGICMWyPx8l13zFjYLrXVMyRShjKR37LPocorU2RtlFPXIuMRVRmlGAo2NU7wy5s--t9u7hCcP8Qxrq39G_1phk96HpjtjCoAH5-ECiZfRclDWHdQys7Ls.1IHrSO59BieaFwX9hr5Z0-qsYqEwVl9dYKUJAKMydVU&dib_tag=se&hvadid=83425841660837&hvbmt=be&hvdev=c&hvlocphy=88716&hvnetw=o&hvqmt=e&hvtargid=kwd-83426611059650:loc-190&hydadcr=1608_13458094&keywords=little+torch&mcid=c2a2e441071730048dc689a6df1b966e&msclkid=3dc77e191c6118f0b8b2168341b8227c&qid=1754947040&s=hi&sr=1-1-spons&sp_csd=d2lkZ2V0TmFtZT1zcF9hdGY&psc=1] I bought one, thinking they were the same, but they are not the same by a long shot! They look identical, but the Chinese knock off is made of inferior material and the critical machining of the tips is reportedly quite variable. The one I bought had a serious leak in the oxy hose due to a faulty hose clamp. I hate to admit it, but took me some time to test for the obvious: a leak in the supply hose. I just assumed that wasn't a defect any manufacturer would allow to leave their factory. (I've learned a lot about doing business with Chinese manufacturers since.) The price of the American original is probably steep for many beginning modelers, but while there are lots of less expensive alternatives, it's been my experience that a soldering rig is one of those tools that one is better off buying the best they can afford. Those will last a lifetime and hold a solid resale value if you ever want to get rid of them. My knock off works great now that I've gone over it with a fine toothed comb, but I would never have bought it had I realized at the time that it was not the "little torch" everybody recommended. If you get one, make sure it is a Made in USA Smith's Little Torch and save yourself the worry about an accident caused by Chinese export quality control.

(6.) Treat yourself to a Quadhands soldering stand. These clever "helping hands" tools are made for holding parts like printed circuit boards for soldering in the high-tech industry. Get one and you'll never use your classic "helping hands" stand with the ball joints tightened with the perpetually loosening wingnuts for anything other than a paperweight. I would put this in my list of essential ship modeling tools. Not only is it infinitely adjustable with its arms set anywhere on the heavy metal base courtesy of rare earth magnets, but its strong bendable arms and alligator clip ends will firmly hold not only multiple parts for soldering but also are really handy for all sorts of rigging chores like stropping and whipping blocks and holding spars for rigging off their mast. Unfortunately, like the Little Torch mentioned above, the internet is full of identically appearing Far Eastern Quadhands knock-offs made by twelve-year-olds chained to their workbenches. As usual, the quality of the counterfeits is below that of the real McCoy. Quadhands come in a variety of sizes and configurations and additional arms can be purchased separately. Prices are very reasonable. Accept no substitutes! (See: https://www.quadhands.com/)

With soldering, as most things, practice makes perfect. The more you practice, the better, and faster, you'll get. It's entirely possible to solder near invisible joints with a bit of practice and care. Don't be intimidated. Once you've got it down, you'll probably find yourself replacing a lot of kit-provided white metal castings with scratch-built brass and copper parts!

A good book on model soldering to have on your research library shelf is Model Building with Brass by Kenneth Foran. (See: https://www.amazon.com/Model-Building-Brass-Kenneth-Foran/dp/0764340042 )

Thanks for your expert advice, most of the tools you mentioned are not available here in Aruba. ... main problem was that my tip of the soldering iron was in bad shape and was getting too hot. sed the 35watt iron. last ones i did where with the 25 watt iron and that made huge difference. I used the bright colored brass wire. straightened it in vise with drill on other end this makes it straight and much stiffer.

Kevin Kenny, who lives in Trinidad and posts a lot of nice ship modeling YouTube content, mentioned he had the same problem with sourcing tools and materials. He explained that he had a daughter living in the States and he'd have her order what he needed and then he'd bring it all back with him when he visited her.

A beat up soldering iron tip can usually be brought back to life by filing the point down to the bright metal (usually copper.) Once the tip is filed down to bright metal, it can be tinned with a bit of solder and you're good to go.

I'm always suspicious of "bright colored brass wire," especially the type bought at craft stores, until I can be sure it's not coated with anything to keep it looking bright. The coated stuff is impossible to solder until the coating is sanded off of it, which is a huge pain in the butt. Of course, if it's coated, it cannot be blackened with liver of sulfur, either.

Wire can also be straightened by putting one end in a vise and grabbing the other end with a pair of pliers and giving it a good hard pull. Twisting it with a drill motor probably does the same because the twists will shorten the wire, and that will harden it up, I expect, but it seems like more work than necessary to get a straight wire. Whatever works is fine, though. The twisting technique is news to me. I'll have to try it the next time I have an occasion to straighten a wire.

A vice and a hand drill are what I use for straightening copper and galvanized steel wire. Haven’t tried with brass since I can get grass rods up to 1m long locally.