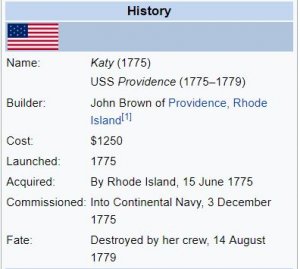

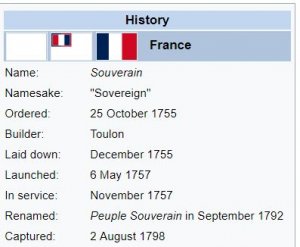

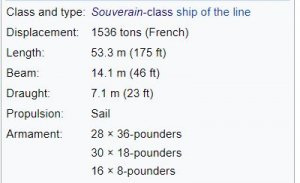

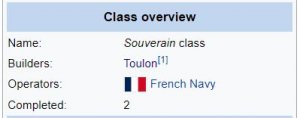

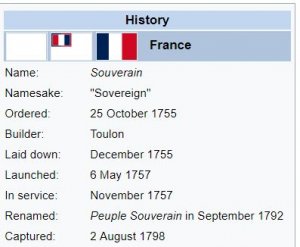

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

7 May 1694 - Henry Every (also spelled Avery) leads a mutiny aboard the privateer Charles II anchored off La Coruna, Spain.

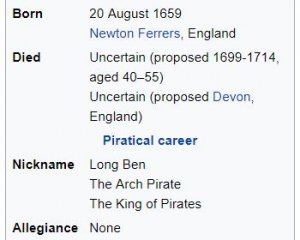

Henry Every, also

Avery or

Evory (20 August 1659 – time of death uncertain), sometimes erroneously given as

Jack Avery or

John Avery, was an English

pirate who operated in the

Atlantic and

Indian oceans in the mid-1690s. He probably used several aliases throughout his career, including

Benjamin Bridgeman, and was known as

Long Ben to his crewmen and associates.

Dubbed "The Arch Pirate" and "The King of Pirates" by contemporaries, Every was infamous for being one of few major pirate captains to escape with his loot without being arrested or killed in battle, and for being the perpetrator of what has been called the most profitable pirate heist in history. Although Every's career as a pirate lasted only two years, his exploits captured the public's imagination, inspired others to take up piracy, and spawned works of literature.

Every began his pirate career while he was

first mate aboard the warship

Charles II. As the ship lay anchored in the northern Spanish harbor of

Corunna, the crew grew discontented as Spain failed to deliver a

letter of marque and

Charles II's owners failed to pay their wages, and they mutinied.

Charles II was renamed the

Fancy and Every elected as the new captain.

A

woodcut from

A General History of the Pyrates (1725) showing a

moor escorting Captain Every

His most famous raid was on a 25-ship convoy of

Grand Mughal vessels making the

annual pilgrimage to

Mecca, including the treasure-laden

Ghanjah dhowGanj-i-sawai and its escort, the

Fateh Muhammed. Joining forces with several pirate vessels, Every found himself in command of a small pirate squadron, and they were able to capture up to £600,000 in precious metals and jewels, equivalent to around £89.6 million in 2019, making him the richest pirate in the world. This caused considerable damage to England's fragile

relations with the Mughals, and a combined bounty of £1,000—an immense sum at the time—was offered by the

Privy Council and the

East India Company for his capture, leading to the first worldwide

manhunt in recorded history.

Although a number of his crew were subsequently arrested, Every himself eluded capture, vanishing from all records in 1696; his whereabouts and activities after this period are unknown. Unconfirmed accounts state he may have changed his name and retired, quietly living out the rest of his life in either Britain or an unidentified tropical island, while alternative accounts consider Every may have squandered his riches. He is considered to have died anywhere between 1699 and 1714; his treasure has never been recovered.

Piratical career

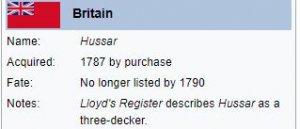

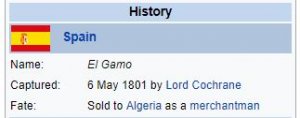

Spanish Expedition Shipping

In the spring of 1693, several London-based investors led by Sir

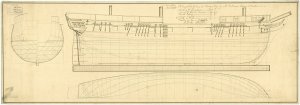

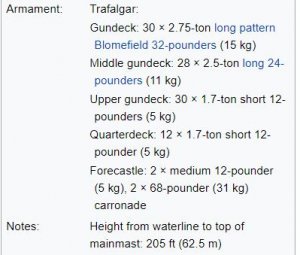

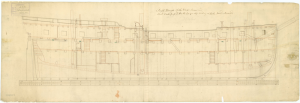

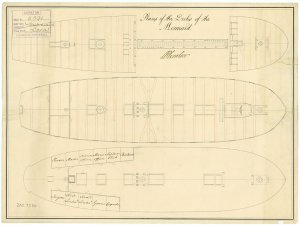

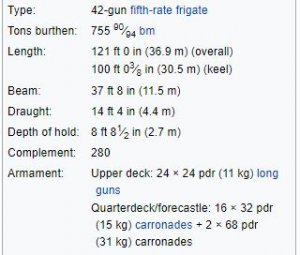

James Houblon, a wealthy merchant hoping to reinvigorate the stagnating English economy, assembled an ambitious venture known as the Spanish Expedition Shipping. The venture consisted of four warships: a

pink, the

Seventh Son, as well as the

frigates Dove (of which famed navigator

William Dampier was second mate), the

James and the

Charles II (sometimes erroneously given as

Duke).

Charles II had been commissioned by England's ally,

Charles II of Spain (the ship's namesake), to prey on French vessels in the

West Indies. Under a trading and salvage license from the Spanish, the venture's mission was to sail to the

Spanish West Indies, where the convoy would conduct trade, supply the Spanish with arms, and recover treasure from wrecked galleons while plundering the

French possessions in the area. The investors promised to pay the sailors well: the contract stipulated a guaranteed monthly wage to be paid every six months throughout deployment, with the first month's pay paid in advance before the start of the mission. Houblon personally went aboard the ships and met the crew, reassuring them of their pay. Indeed, all wages up to 1 August 1693, not long before the start of the mission, were paid on that date.

An 1837 woodcut from

The Pirates Own Book by

Charles Ellms depicting Henry Every receiving three chests of treasure on board his ship, the

Fancy

As a result of his previous experience in the navy, Every was promoted to first mate after joining the Spanish Expedition. The convoy's four ships were commanded by Admiral Sir Don Arturo O'Byrne, an Irish nobleman who had previously served in the

Spanish Navy Marines. This was an odd occurrence at the time and many people thought it boded ill for an Irishman to control an English fleet. Indeed, the voyage was soon in trouble, as the

flag captain,

John Strong, a career mariner who had previously served with Sir

William Phips, died while the ship was still in port. Although he was replaced by Captain Charles Gibson, this would not be the last of the venture's misfortunes.

By early August 1693, the four warships were sailing down the

River Thames en route to Spain's northern city of

Corunna. The journey to Corunna should have taken two weeks, but for some reason the ships did not arrive in Spain until five months later. Worse still, the necessary legal documents had apparently failed to arrive from

Madrid, so the ships were forced to wait. As months passed and the documents still did not arrive, the sailors found themselves in an unenviable position: with no money to send home to support their families and unable to find alternative sources of employment, they had become virtual prisoners in Corunna.

After a few months in port, the men petitioned their captain for the pay they should have received since their employment began. If this request had been granted, the men would no longer have been tied to the ship and could easily have left, so predictably their petition was denied. After a similar petition to James Houblon by the men's wives had also failed, many of the sailors became desperate, believing that they had been sold into slavery to the Spanish.

On 1 May, as the fleet was finally preparing to leave Corunna, the men demanded their six months of pay or threatened to strike. Houblon refused to acquiesce to these demands, but Admiral O'Byrne, seeing the seriousness of the situation, wrote to England asking for the money owed to his men. However, on 6 May some of the sailors were involved in an argument with Admiral O'Byrne, and it was probably around this time that they conceived of a plan to mutiny and began recruiting others. One of the men recruiting others was Henry Every. As William Phillips, a mariner on the

Dove, would later testify, Every went "up & down from Ship to Ship & persuaded the men to come on board him, & he would carry them where they should get money enough." Since Every had a great deal of experience and was also born in a lower social rank, he was the natural choice to command the mutiny, as the crew believed he would have their best interests at heart.

Mutiny and ascension to captaincy

On Monday, 7 May 1694, Admiral O'Byrne was scheduled to sleep ashore, which gave the men the opportunity they were looking for. At approximately 9:00 p.m., Every and about twenty-five other men rushed aboard the

Charles II and surprised the crew on board. Captain Gibson was bedridden at the time, so the mutiny ended bloodlessly. One account states that the extra men from the

James pulled up in a

longboat beside the ship and gave the password, saying, "Is the drunken boatswain on board?" before joining in the mutiny. Captain Humphreys of the

James is also said to have called out to Every that the men were deserting, to which Every calmly replied that he knew perfectly well. The

James then fired on the

Charles II, alerting the Spanish Night Watch, and Every was forced to make a run to the open sea, quickly vanishing into the night.

Declaration of Henry Every to English ship commanders

:To all English Commanders lett this Satisfye that I was Riding here att this Instant in ye Ship fancy man of Warr formerly the Charles of ye Spanish Expedition who departed from Croniae [Corunna] ye 7th of May. 94: Being and am now in A Ship of 46 guns 150 Men & bound to Seek our fortunes I have Never as Yett Wronged any English or Dutch nor never Intend while I am Commander. Wherefore as I Commonly Speake wth all Ships I Desire who ever Comes to ye perusal of this to take this Signall that if you or aney whome you may informe are desirous to know wt wee are att a Distance then make your Antient [i.e., ensign, flag] Vp in a Ball or Bundle and hoyst him att ye Mizon Peek ye Mizon Being furled I shall answere wth ye same & Never Molest you: for my Men are hungry Stout and Resolute: & should they Exceed my Desire I cannott help my selfe.as Yett

An Englishman's friend,At Johanna [Anjouan] February 28th, 1694/5

Henry Every

Here is 160 od french Armed men now att Mohilla who waits for Opportunity of getting aney ship, take Care of your Selves.

After sailing far enough for safety, Every gave the non-conspirators a chance to go ashore, even deferentially offering to let Captain Gibson command the ship if he would join their cause. According to

Charles Ellms, Every's words to Gibson were, "if you have a mind to make one of us, we will receive you; and if you turn sober, and attend to business, perhaps in time I may make you up of my lieutenants; if not, here's a boat, and you shall be set on shore." The captain declined and was set ashore with several other sailors. The only man who was prevented from voluntarily leaving was the ship's surgeon, whose services were deemed too important to forgo. All of the men left on board the

Charles II unanimously elected Every captain of the ship. Some reports say that Every was much ruder in his dealings with Captain Gibson, but agree that he at least offered him the position of second mate. In either case, Every exhibited an amount of gentility and generosity in his operation of the mutiny that indicates his motives were not mere adventure.

Every was easily able to convince the men to sail to the Indian Ocean as pirates, since their original mission had greatly resembled piracy and Every was renowned for his powers of persuasion. He may have mentioned

Thomas Tew's success capturing an enormous prize in the

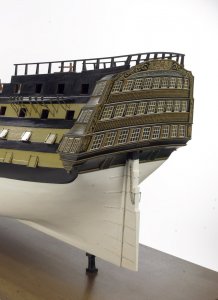

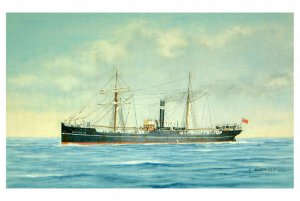

Red Sea only a year earlier. The crew quickly settled the subject of payment by deciding that each member would get one share of the treasure, and the captain would get two. Every then renamed the

Charles II the

Fancy—a name which reflected both the crew's renewed hope in their journey and the quality of the ship—and set a course for the

Cape of Good Hope.

The Pirate Round

At

Maio, the easternmost of the

Cape Verde's

Sotavento islands, Every committed his first piracy, robbing three English merchantmen from

Barbadosof provisions and supplies. Nine of the men from these ships were quickly persuaded to join Every's crew, who now numbered about ninety-four men. Every then sailed to the

Guinea coast, where he tricked a local chieftain into boarding the

Fancy under the false pretense of trade, and forcibly took his and his men's wealth, leaving them slaves. Continuing to hug the African coastline, Every then stopped at

Bioko in the

Bight of Benin, where the

Fancy was

careened and

razeed. By cutting away some of the

superstructure to improve the ship's speed, the

Fancy became one of the fastest vessels then sailing in the Atlantic Ocean. In October 1694, the

Fancy captured two Danish privateers near the island of

Príncipe, stripping the ships of

ivory and gold and welcoming approximately seventeen defecting Danes aboard.

In early 1695, the

Fancy finally rounded the Cape of Good Hope, stopping in Madagascar where the crew restocked supplies, likely in the area of St. Augustine's Bay. The

Fancy next stopped at the island of

Johanna in the

Comoros Islands. Here Every's crew rested and took on provisions, later capturing a passing French pirate ship, looting the vessel and recruiting some forty of the crew to join his own company. His total strength was now about 150 men.

At Johanna, Every wrote a letter addressed to the English ship commanders in the Indian Ocean, falsely stating that he had not attacked any English ships. His letter describes a signal English skippers could use to identify themselves so he could avoid them, and warns them that he might not be able to restrain his crew from plundering their ships if they failed to use the signal. It is unclear whether this document was true, but it may have been a ploy by Every to avoid the attention of the

East India Company, whose

large and powerful ships were the only threat the

Fancy faced in the Indian Ocean. Either way, the letter was unsuccessful in preventing the English from pursuing him.

......... read more about the career in wikipedia ........

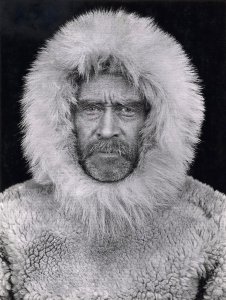

An 18th-century depiction of Henry Every, with the

Fancy shown engaging its prey in the background

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

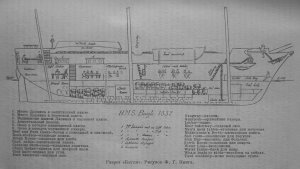

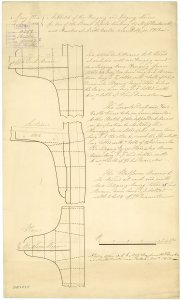

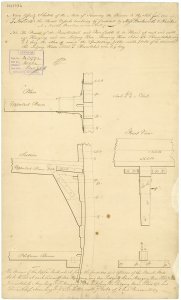

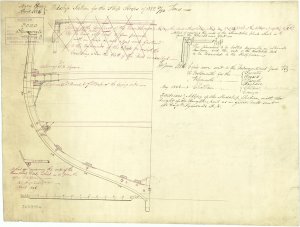

reel, showing the bow nearing the ground.

reel, showing the bow nearing the ground.