This turning into another fascinating discussion.

Going back to first principles, in the days when axe and adze were ruling, what do you do when you want to build a bigger curvier frame than any lump of wood in your yard or growing in your forest? You have to joint it from smaller stock. Now you have the difficulty that you have no glue capable of securing wood together. Like your shore based medieval carpenter then, you need to cut a joint which will resist the stresses on it, and you have no salt resisting metals. You already know about the rot that iron induces in oak, your preferred strong timber.

No glue, no iron - make oak nails. You can make flat bits to produce the holes, and your nails will swell to make them watertight. If you make your frames from overlapping layers and trenail them together you have your solution. An added benefit is that the material is ‘solid oak’ all the way through, so no problem if you need to adze away a bit later, but the added difficulty is that to give enough strength to your trenail you need a big hole - big enough to weaken the parts, so you have to be careful about placement, and you need to avoid lines of holes, so stagger the positions wherever possible.

You most definitely do not want metal fixings wherever you cannot monitor them for rot - either of themselves or the surrounding timber.

Move on a couple of centuries, and metallurgy makes progress enough to produce bronze screws and bolts, and gluetech produces casein’s and epoxies that don’t fall apart in the ocean. Now you can produce boats entirely differently. Diagonal planking! A new thing! Laminated frames - that stay together until the timber fibres themselves rot away.

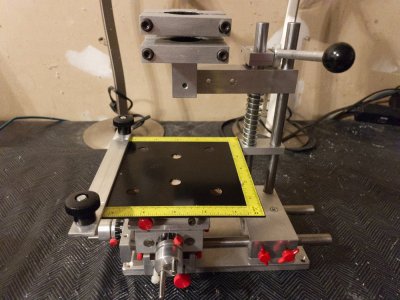

Going back to the plot though, as others have said - your model, your look. Harold Underhill talks of producing dowels in sizes down to number 80 (0.343mm) to secure deck fixings. He had a ‘thing’ about never relying on glue alone though. If you make up a dowel plate you too can produce your own trenails to scale sizes. Bamboo is useful at those scales, though you may find that boxwood gives a better appearance.

Personally,, I like the appearance of brass against timber, but it demands that you use solid backed abrasives, so have to make up slips by gluing metal grade abrasive (emery) to backing boards to prevent hollows forming. Over time, too, brass will oxidise, and it is impossible to polish up in some places. Still, Boulle work has had this problem for 300 years, and we have excellent lacquers nowadays, so as long as care is taken in pre finishing and assembly all will be well.

Summary:-

Do it your way.

J