.

Four years of the most intensive research I could muster has led me to realise that tired rhetoric, devoid of any substantial basis is all that the "students" of naval history is interested in hearing. Inconsistent findings, blatantly misinterpreted information, national misrepresentation, glaring omissions, extreme rudeness and a general disinterest in going beyond the known are all justified at the hand of authored works produced with the sole aim of monetary gain and personal fame - certainly not at finding the facts.

Somehow, I'm still in my thoughts with the archaeological monograph of La Belle 1684 by Texas A&M University Press. Maybe it's because it's a new acquisition, but probably more because I can't get out of my amazement how the analysis and conclusions about the ship itself (as hopefully opposed to its cargo and equipment) can be so badly messed up. The conceptual method was not recognised correctly, the structural features (limber holes) were not recognised correctly, in fact the general type of ship was not even recognised correctly.

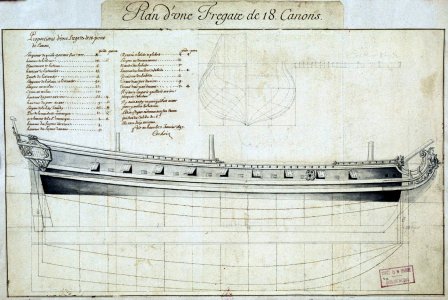

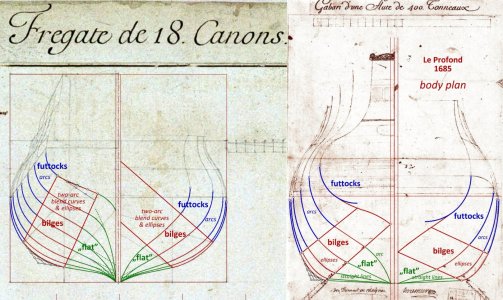

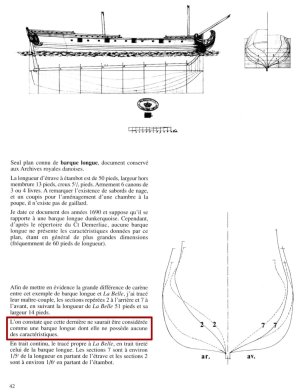

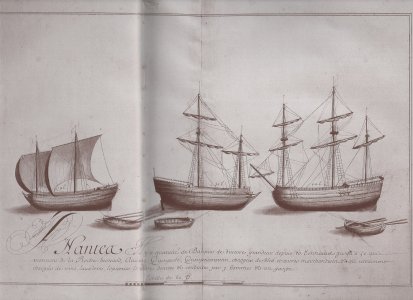

The latter is actually evidenced by the fact that completely inappropriate iconography and ship types of the period (barque longue or light frigate) are reproduced and – necessarily quite chaotically – discussed in the monograph, but there is not even a single depiction and commentary on the right type, i.e. the merchant barque of the Atlantic coast of France (Ponant), after all, with so many examples available in a very close chronologically album of ships — Dessins des différentes maniéres de vaisseaux que l'on voit dans les havres, ports et riviéres depuis Nantes jusqu'à Bayonne qui servent au commerce des sujets de Sa Majesté, 1679.

Be that as it may, here are some relevant examples from this album, which could be already included, together with an appropriate commentary, in a possible second edition of the monograph:

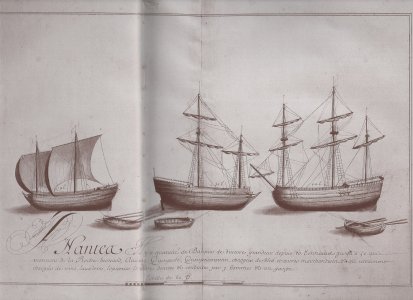

Planche 4. Nantes (samples of merchant barques):

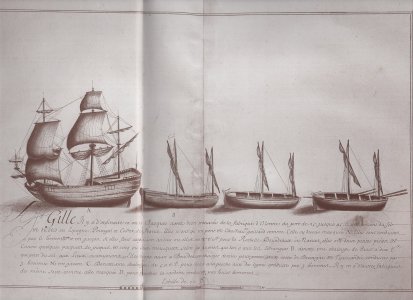

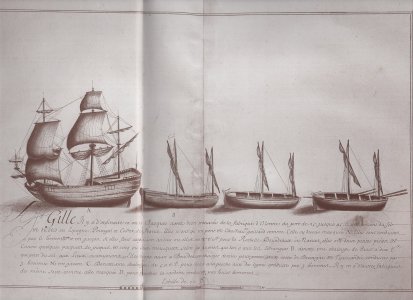

Planche 6. Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie (sample of merchant barque):

* * *

Planche 6. Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie (sample of merchant barque):

* * *

Taking this opportunity, I cannot deny myself a few quotes from a post-publication review of the La Belle monograph (International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 2017.46.2, p. 468–470):

'[…] magnum opus has now arrived […]'.

'[…] meticulously analysed finds underlines both the significance of the wreck and the thoroughness of its investigation'.

'[…] informed mentoring by some of the world’s foremost scholars in the field (not just individual supervisors, but the entire faculty was available for consultation), working within a critical academic culture and drawing on the resources of INA has proven highly productive'.

'The close study and detailed recording of the structure has yielded comprehensive data about a specialized exploratory vessel [? – mine] at a crucial period in global history, and students of naval architecture will appreciate its significance'.

'As well as its outstanding archaeological worth within the wider discipline and for a more nautically focused readership, this project and its three different but related publications are strong additions to our ethical armoury. For a myriad of reasons […], no treasure-hunting venture could ever hope to emulate such an achievement. The challenge is to convince our terrestrial colleagues, and the public at large, that the glossy self-justifying reports treasure-hunters sometimes produce and call archaeology are not what they purport to be. The La Belle publication trilogy — particularly this volume — counters such falsehoods by example and, in doing so, places the powerful sword of truth in our hands'.

I liked most the phrase ‘The La Belle publication […] places the powerful sword of truth in our hands’.

.