Unfortunately, now that the magic of a quick elapsed-time update is over, you will have to adjust to my usually slow pace of working. If all goes well, tonight, I’ll fit and glue the port side transom plank that abuts the head. I will spend hours doing this.

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Soleil Royal by Heller - an Extensive Modification and Partial Scratch-Build by Hubac’s Historian

- Thread starter Hubac’s Historian

- Start date

- Watchers 80

-

- Tags

- 1689 heller hubac refit soleil royal

It is amazing what you showed us already - and we can easily wait for the next updates - a little bit like before christmas, waiting for the coming update

Very detailed and nice work Marc!

Many thanks, Zoly!

So very glad to see you here Marc, as always I'll be following your incredible build. I have so much enjoyed following this build log throughout the years, Thanks Again

Haha! It is so nice to see familiar friends, here, on SOS! Thank you, Don. I wasn’t going to post the project, here, but I decided to because, going forward, I will compose my posts in Google Drive, before copying and posting to MSW and SOS. Because I do a lot of my blogging on the subway, I was having all kinds of glitchy headaches, as the editor would sometimes lose my content and I’d then have to re-construct it - and YOU know how I can wax on and on! This way, it’s much easier to simply up-load pics into both pages.

I think I will stop at two logs, though . It is a pleasure to join this site, as the community is so welcoming and engaging -just as on MSW. So much great work, here!

I think I will stop at two logs, though . It is a pleasure to join this site, as the community is so welcoming and engaging -just as on MSW. So much great work, here!

Believe it or not, aside from heat-bending the bow extension pieces, the aspect of this whole project that has given me the most trepidation is the planking of the stern counter/false balcony. The reason being that this feature of stern architecture took me the longest time to even understand.

Initially, I thought this reverse curve was a seamless transition into the lower tier of lights. The St. Philippe monograph, on the other hand, illustrated that, no, there needs to be a slight projection away from the plane of lights; a sort of shelf, if you will, that ultimately supports a fairly substantial transitional moulding.

This transitional moulding/shelf supports the four seasons figures that support the walkable balcony above. Not only that, but the run of the counter must smoothly accommodate the compound curves of camber and round-up, around one particularly tight bulkhead radius.

Taking a look back, before paint, and in relation to Mr. Lemineur’s drawing of the stern, you can see that my extension piece is absent of this ledge:

Once I realized this mistake, I grafted a ledge extension into the existing plank rebate of my first extension, and then recut that planking rebate into the shelf extension; all very fiddly business, and in the absence of a comprehensive plan to work from, the shape I patterned for this shelf was something of an aesthetic approximation. As fairing of these bulkheads has progressed, the extension pieces were pared down to their final shape.

As a side note, it is kind of hilarious to me that I took such pains to cut this plank rebate into the ends of the lower hull and upper bulwarks - both to provide a glue ledge for the plank ends, and also to bring the side plank butt ends down to scale - only to realize that in the end, they will mostly be covered. Except for the area between the waterline and the transom moulding, everything above gets covered; first by the wrap-around of the quarter gallery lower finishing, and then, by pilaster mouldings, all above. At least the beakhead bulkhead will still show this detail

Digressions aside - one must finally add to this equation the fact that I want to seamlessly incorporate Louis’ angelic little head into the run of the counter, and all of that becomes quite challenging to make look right.

While laying the lowest, first course of counter planking, I realized that I would be better served by simply butting the planks flush with the edges of the head ornament, and not adding that slight bevel to the plank edges around the head. The reason for this is that the border that the head creates is kind of irregular and a little jagged.

Following all of that closely with a bevel - no matter how carefully done - would look jagged and horrible. Because there will be at least another two planking layers around the head, I can create a smooth radius around the head, with those layers, and then bevel them, inward toward the head, in order to give it a sense of concavity.

With that all settled, the first two courses went down smoothly. The run, along the bulkheads, there, is fairly flat. I was very careful to let-in as closely as I could around the crown. For the third, and top-most course, around the tight radius of the bulkhead frames, I discovered that I needed a plank just a little bit wider than the 5/32” that I used for the two coarses above.

I was hoping to avoid laying two very narrow planks, so instead I ripped one plank to 3/16”+, and then engraved a line down it’s center, on the plank backside. This effectively created a bending crease that eased the transition around this tight radius, while eliminating any possibility of plank gaps. So, the rough, before fairing, was looking pretty promising:

After fairing, things were looking a lot better. I sanded the top edge of the counter planking so that I would have an even 1/16” space, beneath the window frames, for the transitional moulding. This enabled me to fit and glue-in the pilasters between windows. I will be trimming the tops of these pilasters flush with the window plate, before glueing, and the outer pilasters will be glued in after the plate is installed, because they overlay the ship’s side planking:

I can now go ahead and spray-prime the window plate, so that I can paint-in the inner edges of the window frames with yellow ocher, before installing the glass panes.

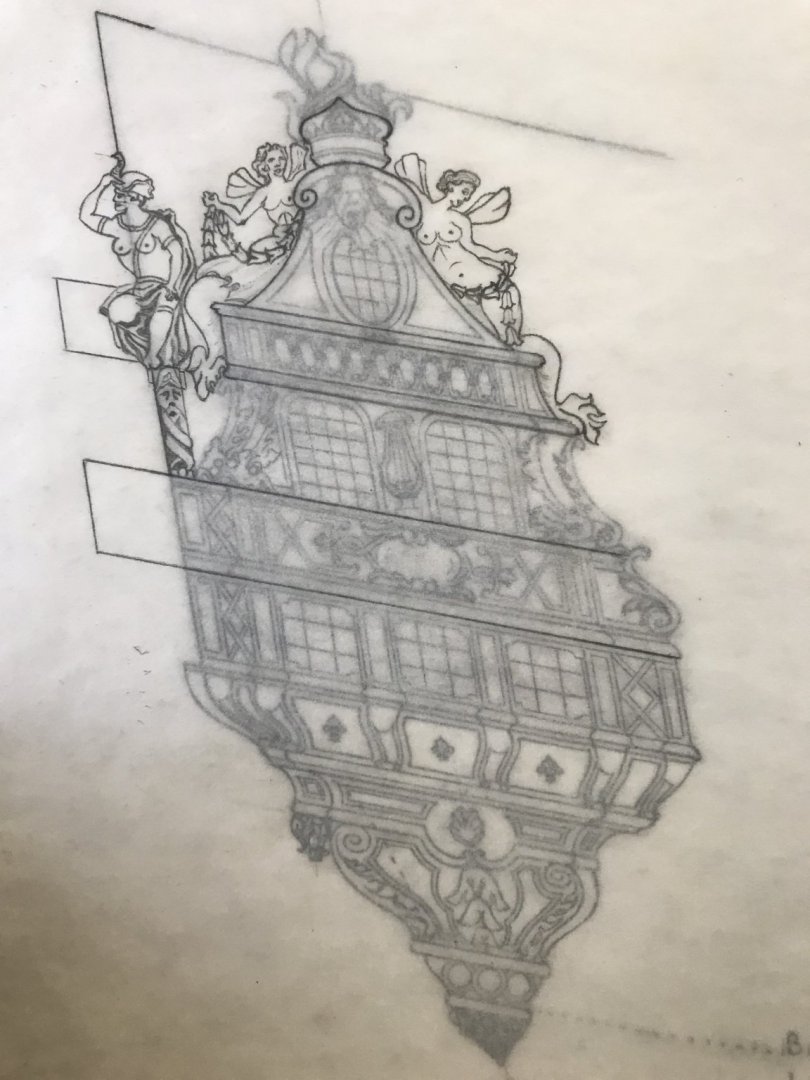

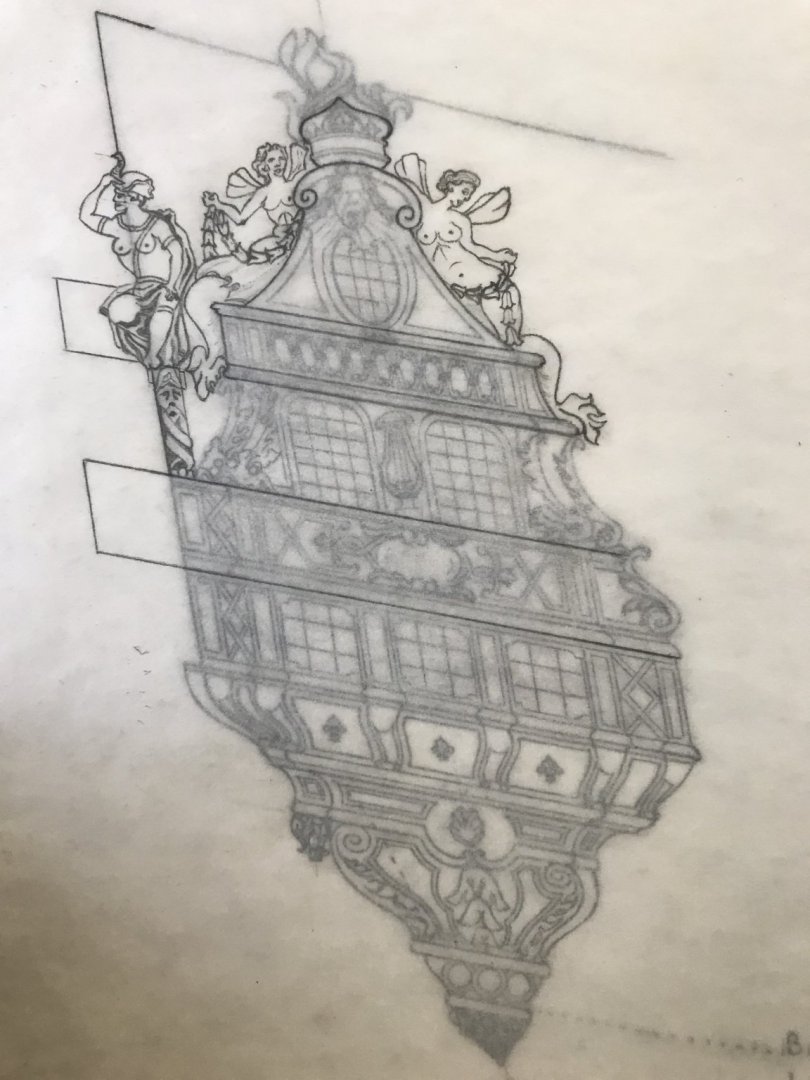

So, now that we have a good and fair foundation to work from, I can begin playing with the artistic layout of the counter. Here is what Berain drew:

The layout revolves around this central panel, spanning the middle four windows, which projects further outboard than the paneled sides. Interspersed along the counter, are the four pedestal bases that visually support the Four Seasons figures. These pedestals will stand proud of their respective backing surfaces, and the central two must project far enough that they are just proud of the lambrequin carving that bridges between them.

If I get the proportions of all of this right, and the shape and raking angles of the pedestal bases aesthetically right, then the entire ensemble will convey a similar sense of elegant proportion, even though the profile of my stern is more vertically oriented, and less sloping than what Berain drew. This is an artistic process that begins, simply by sketching a few primary parameters directly onto the model; in this case, the outside edges of the central panel, as well as the circular framework of the paneled sides:

It is the pilasters between the 1st and 2nd/5th and 6th windows that mark the location for the figures of Spring and Summer, and thus delineate the outside breadth of the central panel.

In the Tanneron version, there is no circular paneling to the sides of the central panel. He seems, instead, to have created these circular medallions:

To include this detail on my model, I will have to strike a delicate balance between the diameter of those circles, so that there is enough space left over for the paneled sections to either side of the circles. This may mean reducing the outer breadth of the central section, and simplifying the design to only include the raised cyma projection of the pedestals, themselves.

In my rough sketching, above, I’ve drawn two dotted lines. The outer line represents the raised ground to which the pedestal is mounted, as Berain designed it. If I eliminate that line, I’ll have a little extra room for the side panels. Tonight, I’ll make better sketches and see where I end up.

Once I like the spacing of all the various elements, I’ll make an oak tag tracing pattern for the center pedestals, and a pattern for the outer pedestals, which are raked at a different angle. I can then use the middle pedestal pattern to draw the outer breadth of the center section, so that I can begin planking that section.

The oak tag patterns, together, can then be used to frame-in the side panel shapes onto slightly thinner styrene sheet. All will become clearer, as I go.

As ever, thank you for your likes, comments and looking in.

-HH

Initially, I thought this reverse curve was a seamless transition into the lower tier of lights. The St. Philippe monograph, on the other hand, illustrated that, no, there needs to be a slight projection away from the plane of lights; a sort of shelf, if you will, that ultimately supports a fairly substantial transitional moulding.

This transitional moulding/shelf supports the four seasons figures that support the walkable balcony above. Not only that, but the run of the counter must smoothly accommodate the compound curves of camber and round-up, around one particularly tight bulkhead radius.

Taking a look back, before paint, and in relation to Mr. Lemineur’s drawing of the stern, you can see that my extension piece is absent of this ledge:

Once I realized this mistake, I grafted a ledge extension into the existing plank rebate of my first extension, and then recut that planking rebate into the shelf extension; all very fiddly business, and in the absence of a comprehensive plan to work from, the shape I patterned for this shelf was something of an aesthetic approximation. As fairing of these bulkheads has progressed, the extension pieces were pared down to their final shape.

As a side note, it is kind of hilarious to me that I took such pains to cut this plank rebate into the ends of the lower hull and upper bulwarks - both to provide a glue ledge for the plank ends, and also to bring the side plank butt ends down to scale - only to realize that in the end, they will mostly be covered. Except for the area between the waterline and the transom moulding, everything above gets covered; first by the wrap-around of the quarter gallery lower finishing, and then, by pilaster mouldings, all above. At least the beakhead bulkhead will still show this detail

Digressions aside - one must finally add to this equation the fact that I want to seamlessly incorporate Louis’ angelic little head into the run of the counter, and all of that becomes quite challenging to make look right.

While laying the lowest, first course of counter planking, I realized that I would be better served by simply butting the planks flush with the edges of the head ornament, and not adding that slight bevel to the plank edges around the head. The reason for this is that the border that the head creates is kind of irregular and a little jagged.

Following all of that closely with a bevel - no matter how carefully done - would look jagged and horrible. Because there will be at least another two planking layers around the head, I can create a smooth radius around the head, with those layers, and then bevel them, inward toward the head, in order to give it a sense of concavity.

With that all settled, the first two courses went down smoothly. The run, along the bulkheads, there, is fairly flat. I was very careful to let-in as closely as I could around the crown. For the third, and top-most course, around the tight radius of the bulkhead frames, I discovered that I needed a plank just a little bit wider than the 5/32” that I used for the two coarses above.

I was hoping to avoid laying two very narrow planks, so instead I ripped one plank to 3/16”+, and then engraved a line down it’s center, on the plank backside. This effectively created a bending crease that eased the transition around this tight radius, while eliminating any possibility of plank gaps. So, the rough, before fairing, was looking pretty promising:

After fairing, things were looking a lot better. I sanded the top edge of the counter planking so that I would have an even 1/16” space, beneath the window frames, for the transitional moulding. This enabled me to fit and glue-in the pilasters between windows. I will be trimming the tops of these pilasters flush with the window plate, before glueing, and the outer pilasters will be glued in after the plate is installed, because they overlay the ship’s side planking:

I can now go ahead and spray-prime the window plate, so that I can paint-in the inner edges of the window frames with yellow ocher, before installing the glass panes.

So, now that we have a good and fair foundation to work from, I can begin playing with the artistic layout of the counter. Here is what Berain drew:

The layout revolves around this central panel, spanning the middle four windows, which projects further outboard than the paneled sides. Interspersed along the counter, are the four pedestal bases that visually support the Four Seasons figures. These pedestals will stand proud of their respective backing surfaces, and the central two must project far enough that they are just proud of the lambrequin carving that bridges between them.

If I get the proportions of all of this right, and the shape and raking angles of the pedestal bases aesthetically right, then the entire ensemble will convey a similar sense of elegant proportion, even though the profile of my stern is more vertically oriented, and less sloping than what Berain drew. This is an artistic process that begins, simply by sketching a few primary parameters directly onto the model; in this case, the outside edges of the central panel, as well as the circular framework of the paneled sides:

It is the pilasters between the 1st and 2nd/5th and 6th windows that mark the location for the figures of Spring and Summer, and thus delineate the outside breadth of the central panel.

In the Tanneron version, there is no circular paneling to the sides of the central panel. He seems, instead, to have created these circular medallions:

To include this detail on my model, I will have to strike a delicate balance between the diameter of those circles, so that there is enough space left over for the paneled sections to either side of the circles. This may mean reducing the outer breadth of the central section, and simplifying the design to only include the raised cyma projection of the pedestals, themselves.

In my rough sketching, above, I’ve drawn two dotted lines. The outer line represents the raised ground to which the pedestal is mounted, as Berain designed it. If I eliminate that line, I’ll have a little extra room for the side panels. Tonight, I’ll make better sketches and see where I end up.

Once I like the spacing of all the various elements, I’ll make an oak tag tracing pattern for the center pedestals, and a pattern for the outer pedestals, which are raked at a different angle. I can then use the middle pedestal pattern to draw the outer breadth of the center section, so that I can begin planking that section.

The oak tag patterns, together, can then be used to frame-in the side panel shapes onto slightly thinner styrene sheet. All will become clearer, as I go.

As ever, thank you for your likes, comments and looking in.

-HH

Last edited:

Marc what an amazing project you have here.

What is the material you use for all your alterations and carvings.

See you are familiar with the work of the Thomesen brothers. They build a complete fleet of resin vessels to display the Dutch fleet in the 17th century at anchor before the island of Texel.

It is a pitty they don't sell these ships as a kit whereas they sell a lot of other models as kit.

See below de reede van Texel.

What is the material you use for all your alterations and carvings.

See you are familiar with the work of the Thomesen brothers. They build a complete fleet of resin vessels to display the Dutch fleet in the 17th century at anchor before the island of Texel.

It is a pitty they don't sell these ships as a kit whereas they sell a lot of other models as kit.

See below de reede van Texel.

Hello Maarten! Thank you for your interest - it is much appreciated!

To answer your question, all of the planking and structural work is white polly-styrene; styrene sheet in various thicknesses, or strip, or rod, or any number of profiled shapes. The repetitive ornaments were cast in resin, from original styrene master carvings. Each individual carving, though, is cleaned up and chased, almost like a metal casting, so they all end up looking a little different.

When I was really starting the fabrication of this project, I thought that I would quickly become proficient in polymerized clay sculpting like the famous card modeler, Doris. She has produced so many instructional videos that I thought I’d just be teasing out incredible sculptures in no time - one after the other!

In practice, of course, what Doris makes to look quite simple, is the product of endless hours of focused skill development. I was quickly frustrated in my attempts at familiarity with Sculpy, and reverted to what I know.

Interestingly, I was just recently looking at closeups of the model that really put Doris on the world stage - The Sovereign of the Seas - and I was struck by how far her sculpture talents have progressed from then to her current build of the Royal Katherine. There is an extra level of refinement to her work, now, that has evolved from the Sovereign, to the Royal Yacht Caroline, to the Katherine. Simply put - it didn’t happen overnight.

As for Herbert Thomesan - he truly is a special individual. I sought him out, in 2003, because I was working as a volunteer at Batavia Werf. He had made a small-scale diorama showing the masting of a mid-rate Dutch frigate for the Werf. I went to visit him at his workshop, in Amsterdam, where he was constructing the Texel diorama, at the time.

He spent about three hours with me, and showed me his entire fabrication process, and even challenged me to use my remaining time in Holland to build a small model of a “Botter” boat, using the techniques that he showed me. He supplied me with vacuu-formed shells, sheet styrene, glue and a resin casting of the finished model that I was copying.

I was learning so many things, in my three months at the Werf, that I never completed the model. I got about half-way there.

In addition to the model, the carving shop master, Timmon, allowed me into his shop at the end of the day, so that I could chip away at my first relief carving. Between working on Batavia in the day, carving in the evening, and working on the model whenever I had enough energy left-over - as well as discovering Belgian ales and traveling around the country... Let’s just say that I was quite busy.

I brought my attempt at the Botter boat back to Herbert, before I left Holland, and he was satisfied that I could eventually become proficient in his technique. What he was looking for was someone who might be interested in modeling the French fleet. He had covered representation of the Dutch and English ships, but he really wanted to incorporate the French portion of the narrative for supremacy of the 17th C. seas.

The essential things that Herbert taught me were that your only limitations were your imagination. Also, that one does not need to get thoroughly bogged-down in drawing out every last detail, as long as the architecture is correct. Lastly, he taught me that truly excellent weathered finishes are much easier to attain than they may seem.

In the end, I came home to New York and got busy trying to become a much better woodworker, and I succeeded at that. After my kids were born, though, I had little time or energy left to master the French fleet. Now that my kids are a little older, I’m really trying (perhaps, foolishly ) to master this one, great French ship.

) to master this one, great French ship.

Occasionally, I’m still in touch with Herbert, and he remains exceedingly helpful to this day.

To answer your question, all of the planking and structural work is white polly-styrene; styrene sheet in various thicknesses, or strip, or rod, or any number of profiled shapes. The repetitive ornaments were cast in resin, from original styrene master carvings. Each individual carving, though, is cleaned up and chased, almost like a metal casting, so they all end up looking a little different.

When I was really starting the fabrication of this project, I thought that I would quickly become proficient in polymerized clay sculpting like the famous card modeler, Doris. She has produced so many instructional videos that I thought I’d just be teasing out incredible sculptures in no time - one after the other!

In practice, of course, what Doris makes to look quite simple, is the product of endless hours of focused skill development. I was quickly frustrated in my attempts at familiarity with Sculpy, and reverted to what I know.

Interestingly, I was just recently looking at closeups of the model that really put Doris on the world stage - The Sovereign of the Seas - and I was struck by how far her sculpture talents have progressed from then to her current build of the Royal Katherine. There is an extra level of refinement to her work, now, that has evolved from the Sovereign, to the Royal Yacht Caroline, to the Katherine. Simply put - it didn’t happen overnight.

As for Herbert Thomesan - he truly is a special individual. I sought him out, in 2003, because I was working as a volunteer at Batavia Werf. He had made a small-scale diorama showing the masting of a mid-rate Dutch frigate for the Werf. I went to visit him at his workshop, in Amsterdam, where he was constructing the Texel diorama, at the time.

He spent about three hours with me, and showed me his entire fabrication process, and even challenged me to use my remaining time in Holland to build a small model of a “Botter” boat, using the techniques that he showed me. He supplied me with vacuu-formed shells, sheet styrene, glue and a resin casting of the finished model that I was copying.

I was learning so many things, in my three months at the Werf, that I never completed the model. I got about half-way there.

In addition to the model, the carving shop master, Timmon, allowed me into his shop at the end of the day, so that I could chip away at my first relief carving. Between working on Batavia in the day, carving in the evening, and working on the model whenever I had enough energy left-over - as well as discovering Belgian ales and traveling around the country... Let’s just say that I was quite busy.

I brought my attempt at the Botter boat back to Herbert, before I left Holland, and he was satisfied that I could eventually become proficient in his technique. What he was looking for was someone who might be interested in modeling the French fleet. He had covered representation of the Dutch and English ships, but he really wanted to incorporate the French portion of the narrative for supremacy of the 17th C. seas.

The essential things that Herbert taught me were that your only limitations were your imagination. Also, that one does not need to get thoroughly bogged-down in drawing out every last detail, as long as the architecture is correct. Lastly, he taught me that truly excellent weathered finishes are much easier to attain than they may seem.

In the end, I came home to New York and got busy trying to become a much better woodworker, and I succeeded at that. After my kids were born, though, I had little time or energy left to master the French fleet. Now that my kids are a little older, I’m really trying (perhaps, foolishly

Occasionally, I’m still in touch with Herbert, and he remains exceedingly helpful to this day.

Last edited:

Marc aside from your great work,your log makes very interesting reading.

Looking at Berain's drawing,what is your take on the side galleries?To me,they are portrayed open in the drawing which contradicts some information on the internet I stumbled upon a good while ago.

There was a picture of an original document issued by Louis ordering that all stern galleries were to be enclosed.This document predated the rebuild of Soleil Royal.

Kind Regards

Nigel

Looking at Berain's drawing,what is your take on the side galleries?To me,they are portrayed open in the drawing which contradicts some information on the internet I stumbled upon a good while ago.

There was a picture of an original document issued by Louis ordering that all stern galleries were to be enclosed.This document predated the rebuild of Soleil Royal.

Kind Regards

Nigel

Hi Marc, so you learned from the master himself, that is obvious in your excellent work.Hello Maarten! Thank you for your interest - it is much appreciated!

To answer your question, all of the planking and structural work is white polly-styrene; styrene sheet in various thicknesses, or strip, or rod, or any number of profiled shapes. The repetitive ornaments were cast in resin, from original styrene master carvings. Each individual carving, though, is cleaned up and chased, almost like a metal casting, so they all end up looking a little different.

When I was really starting the fabrication of this project, I thought that I would quickly become proficient in polymerized clay sculpting like the famous card modeler, Doris. She has produced so many instructional videos that I thought I’d just be teasing out incredible sculptures in no time - one after the other!

In practice, of course, what Doris makes to look quite simple, is the product of endless hours of focused skill development. I was quickly frustrated in my attempts at familiarity with Sculpy, and reverted to what I know.

Interestingly, I was just recently looking at closeups of the model that really put Doris on the world stage - The Sovereign of the Seas - and I was struck by how far her sculpture talents have progressed from then to her current build of the Royal Katherine. There is an extra level of refinement to her work, now, that has evolved from the Sovereign, to the Royal Yacht Caroline, to the Katherine. Simply put - it didn’t happen overnight.

As for Herbert Thomesan - he truly is a special individual. I sought him out, in 2003, because I was working as a volunteer at Batavia Werf. He had made a small-scale diorama showing the masting of a mid-rate Dutch frigate for the Werf. I went to visit him at his workshop, in Amsterdam, where he was constructing the Texel diorama, at the time.

He spent about three hours with me, and showed me his entire fabrication process, and even challenged me to use my remaining time in Holland to build a small model of a “Botter” boat, using the techniques that he showed me. He supplied me with vacuu-formed shells, sheet styrene, glue and a resin casting of the finished model that I was copying.

I was learning so many things, in my three months at the Werf, that I never completed the model. I got about half-way there.

In addition to the model, the carving shop master, Timmon, allowed me into his shop at the end of the day, so that I could chip away at my first relief carving. Between working on Batavia in the day, carving in the evening, and working on the model whenever I had enough energy left-over - as well as discovering Belgian ales and traveling around the country... Let’s just say that I was quite busy.

I brought my attempt at the Botter boat back to Herbert, before I left Holland, and he was satisfied that I could eventually become proficient in his technique. What he was looking for was someone who might be interested in modeling the French fleet. He had covered representation of the Dutch and English ships, but he really wanted to incorporate the French portion of the narrative for supremacy of the 17th C. seas.

The essential things that Herbert taught me were that your only limitations were your imagination. Also, that one does not need to get thoroughly bogged-down in drawing out every last detail, as long as the architecture is correct. Lastly, he taught me that truly excellent weathered finishes are much easier to attain than they may seem.

In the end, I came home to New York and got busy trying to become a much better woodworker, and I succeeded at that. After my kids were born, though, I had little time or energy left to master the French fleet. Now that my kids are a little older, I’m really trying (perhaps, foolishly) to master this one, great French ship.

Occasionally, I’m still in touch with Herbert, and he remains exceedingly helpful to this day.

Doris is indeed also a master in her art of papermodeling, as she is a school teacher I think a lot of us would love to go back to school for some modeling lessons from her.

Although it is not what I ended up doing with my life, my father trained me, first and foremost to be a writer. The absence of boredom is, perhaps, the highest compliment of all. Thank you, Nigel! I am glad that you are enjoying the log.

I am going to begin by answering your question, in brief:

With the absence of a walkable, lower stern balcony, at this later date in 1689, I believe that the lowest tier of the quarter gallery (middle deck level) is fully closed-in. As the functional officers’ toilet, it would make sense that that were so. I also think that, apart from a removable (to the inside) panel, all the lights on this level are false windows.

At the main deck level, I believe that there is a walkable balcony, with access from the stern, that wraps to the quarters. Desclouseaux’s signed survey sketches from 1688, suggest as much.

The two side lights, at this level, were also likely vestigial, with perhaps only a small 4-pane window insert, within the aft vestigial window. I also think it is possible that there was a removable port lid in the forward vestigial window, for an extra couple of artillery pieces.

As a side note, Nigel - I stumbled upon your log and SOS, when I was actually trying to find the most remarkable modern model of L’Ambiteaux that I have ever seen. The model was made by a gentleman whom I seem to remember, called himself Der Admiral. The arsenal site was Italian, as I recall.

I joined the site, in the hope of striking up a correspondence with Der Admiral, because while his wooden model was painted - and very authentically distressed, I might add - his sensitivity to the carved work of the times was absolutely peerless. Better than Tanneron. There - I’ve said it and, so-doing, committed a sacrilege! In my opinion, though, it is the truth.

Because the ornament was also painted, it seemed to me that he must have made it from modeling clay. I wanted to pick his brains about that. He also seemed to represent these particularities of the false side gallery lights to great effect. He had achieved a stylized painting of the glass panes that I would very much like to emulate on my model.

Anyway, I suppose that I was not active enough, early enough on the site, and the administrators shut my account down. Within a week. I had a hot-link to the site on my home computer, but this particular MAC is so old, now, that it just recently died. The screen sort of resembles that stylized glass, when you turn it on - a scramble of jagged lines. Anyway, I was lost, but then I found something equally interesting in your log of the SP, and SOS, at large.

Again - sorry for the digression...

From the stern, the archway supporting the large figures of Africa and the Americas, I believe, is an open pass-through between stern and quarters.

Lastly, at the quarter deck level, I believe that the oval window is an actual glazing set into the shallow relief of the amortisement.

In summary, I think that SR of 1689, has the same basic relationship of stern to quarter, as represented on the St. Philippe of 1693. That is why I became so excited when I first found a few really grainy pictures of Tussett’s model from the Rochefort conference, in 2012.

All of the early reglements, including the one that specified that quarters should be closed, were largely ignored by the master builders in each of the main yards. Laurent Hubac was, perhaps, the most intransigent of all. It is reasonable to suppose that his son, Etienne, was also less inclined to acquiesce to Colbert and the King’s building council, which was largely composed of the ships’ commissioned officers. After all, what did they know about ship-building?! Or, so young Etienne may have thought, at the time.

It appears more likely that the transition to fully closed quarters did not happen until the Second-marine building program was well underway. In fact, it is the second drawing of SR’s quarters, which does correspond very closely to Berain’s stern, that I believe to be an updating of styles for SR2, of 1693. These, I believe to be fully closed in.

That was my “brief” answer to the question. In my next post, I will copy and paste a much more expansive analysis that effectively condenses one half of the 37-page, main build-log into one cogent A-HA! moment, when my thinking on the subject of drawing incongruities really came into focus.

It’s interesting reading...

to those who are interested.

I am going to begin by answering your question, in brief:

With the absence of a walkable, lower stern balcony, at this later date in 1689, I believe that the lowest tier of the quarter gallery (middle deck level) is fully closed-in. As the functional officers’ toilet, it would make sense that that were so. I also think that, apart from a removable (to the inside) panel, all the lights on this level are false windows.

At the main deck level, I believe that there is a walkable balcony, with access from the stern, that wraps to the quarters. Desclouseaux’s signed survey sketches from 1688, suggest as much.

The two side lights, at this level, were also likely vestigial, with perhaps only a small 4-pane window insert, within the aft vestigial window. I also think it is possible that there was a removable port lid in the forward vestigial window, for an extra couple of artillery pieces.

As a side note, Nigel - I stumbled upon your log and SOS, when I was actually trying to find the most remarkable modern model of L’Ambiteaux that I have ever seen. The model was made by a gentleman whom I seem to remember, called himself Der Admiral. The arsenal site was Italian, as I recall.

I joined the site, in the hope of striking up a correspondence with Der Admiral, because while his wooden model was painted - and very authentically distressed, I might add - his sensitivity to the carved work of the times was absolutely peerless. Better than Tanneron. There - I’ve said it and, so-doing, committed a sacrilege! In my opinion, though, it is the truth.

Because the ornament was also painted, it seemed to me that he must have made it from modeling clay. I wanted to pick his brains about that. He also seemed to represent these particularities of the false side gallery lights to great effect. He had achieved a stylized painting of the glass panes that I would very much like to emulate on my model.

Anyway, I suppose that I was not active enough, early enough on the site, and the administrators shut my account down. Within a week. I had a hot-link to the site on my home computer, but this particular MAC is so old, now, that it just recently died. The screen sort of resembles that stylized glass, when you turn it on - a scramble of jagged lines. Anyway, I was lost, but then I found something equally interesting in your log of the SP, and SOS, at large.

Again - sorry for the digression...

From the stern, the archway supporting the large figures of Africa and the Americas, I believe, is an open pass-through between stern and quarters.

Lastly, at the quarter deck level, I believe that the oval window is an actual glazing set into the shallow relief of the amortisement.

In summary, I think that SR of 1689, has the same basic relationship of stern to quarter, as represented on the St. Philippe of 1693. That is why I became so excited when I first found a few really grainy pictures of Tussett’s model from the Rochefort conference, in 2012.

All of the early reglements, including the one that specified that quarters should be closed, were largely ignored by the master builders in each of the main yards. Laurent Hubac was, perhaps, the most intransigent of all. It is reasonable to suppose that his son, Etienne, was also less inclined to acquiesce to Colbert and the King’s building council, which was largely composed of the ships’ commissioned officers. After all, what did they know about ship-building?! Or, so young Etienne may have thought, at the time.

It appears more likely that the transition to fully closed quarters did not happen until the Second-marine building program was well underway. In fact, it is the second drawing of SR’s quarters, which does correspond very closely to Berain’s stern, that I believe to be an updating of styles for SR2, of 1693. These, I believe to be fully closed in.

That was my “brief” answer to the question. In my next post, I will copy and paste a much more expansive analysis that effectively condenses one half of the 37-page, main build-log into one cogent A-HA! moment, when my thinking on the subject of drawing incongruities really came into focus.

It’s interesting reading...

to those who are interested.

Last edited:

Thank you, Maarten!

Yes, Doris truly is incredible in what she manages to achieve. Yes, she works. She plays music. She travels. She builds the Royal Katherine. And she also manages to concurrently build any number of plastic kits, as side builds.

On SOS, she once posted pics of a wholly card model that she had made of her particular Mazda sedan that she has been personally doing all of the mechanical work on for the past, umpteen years! Oh, yeah - Doris is also an accomplished mechanic and completely restored the car

The model of the car? ‘Prolly equally impressive to any of her ship models. It is impossible to believe that she made the thing out of cardboard.

And if all of that weren’t enough, she is humble and exceedingly giving of her time and advice.

She is marveloso!

Yes, Doris truly is incredible in what she manages to achieve. Yes, she works. She plays music. She travels. She builds the Royal Katherine. And she also manages to concurrently build any number of plastic kits, as side builds.

On SOS, she once posted pics of a wholly card model that she had made of her particular Mazda sedan that she has been personally doing all of the mechanical work on for the past, umpteen years! Oh, yeah - Doris is also an accomplished mechanic and completely restored the car

The model of the car? ‘Prolly equally impressive to any of her ship models. It is impossible to believe that she made the thing out of cardboard.

And if all of that weren’t enough, she is humble and exceedingly giving of her time and advice.

She is marveloso!

So, here is that earlier post from the MSW build-log:

__

Now that I have completed my light re-design of the Berain/Vary quarter galleries, I also had time to reflect upon some of the questions and criticisms that scholars levy against the likelihood that they are the rightful companion to the known Berain stern drawing, for this time that I have targeted in 1689.

In correspondence I have held with these individuals, they cite anomalies in the scale and execution of this drawing.

The lower false stern balcony, for example, is grossly exaggerated. They also mention that the relative proportion of the windows at each of the three levels does not neatly correspond with the relative proportions shown on the stern drawing. If that weren’t enough, the diamond-hatch, leaded cames of the lower gallery windows is of the antiquated (First Marine) style, and it does not match the cross-hatched mullions on the stern drawing. I agree that these anomalies are hard to jibe with what is clearly an exquisitely rendered stern drawing, where not one line or detail seems out of proportion or place.

All of these individuals point toward the missing elephantine head-dress of the figure of Africa; has Berain suddenly forgotten that what he shows from the stern perspective must also appear in the quarter view, they wonder? I wonder that too.

Not lastly, but also notably, these individuals point to the mermaid figures as being wholly inconsistent with the stern allegory, and more likely a relic of the earlier First Marine style of ornamentation. Again, I find it hard to argue against these observations.

In fact, I will probably never be able to definitively say that this QG rendering is the hand of Berain, because as these men also point out, it is not archived as a set with the stern drawing. Nevertheless, these considerations won’t stop me from attempting to bolster my central argument - that these stern and quarter drawings do correspond.

And so, ever remaining consistent with my approach to research, I am always studying SR’s better documented contemporaries and near contemporaries in search of structural and ornamental patterns of consistency.

This book, Floating Baroque (thanks again to Heinrich) has been an invaluable resource because it provides me with archival quality reproductions of ornamental sets that are known to correspond with each other, from a specific time, and originating at the hand of Jean Berain.

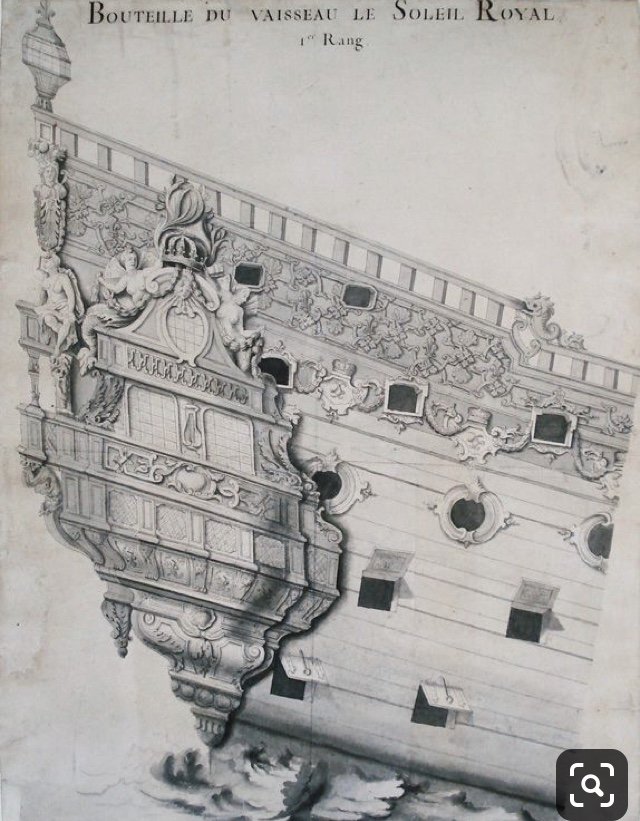

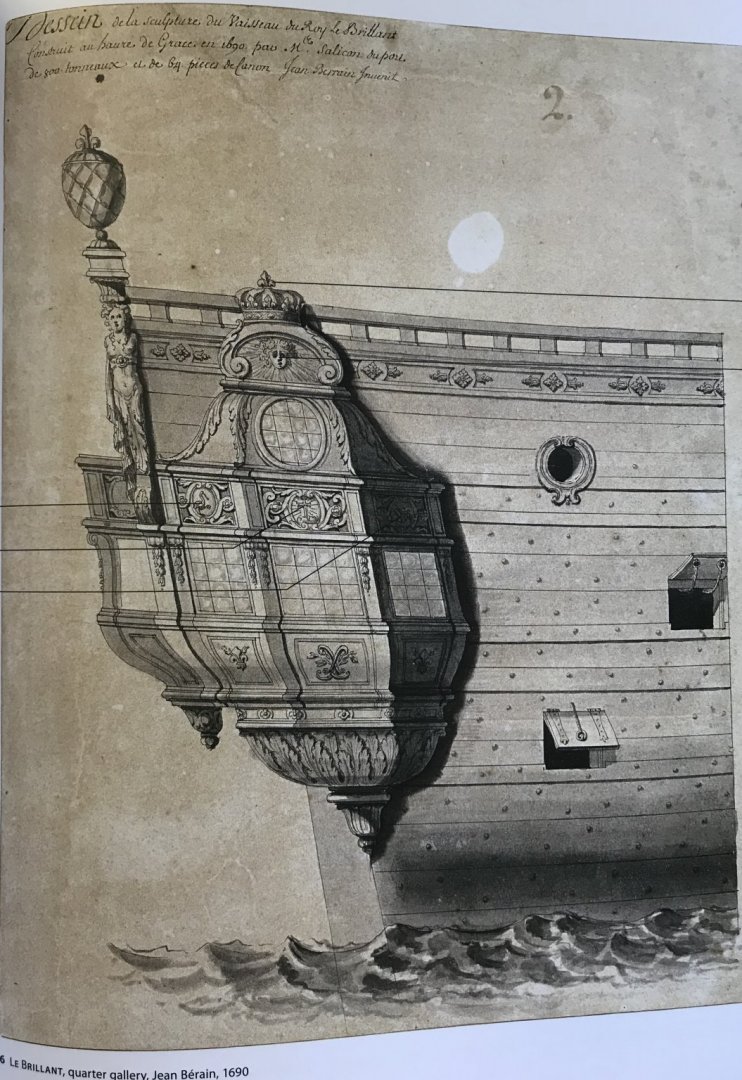

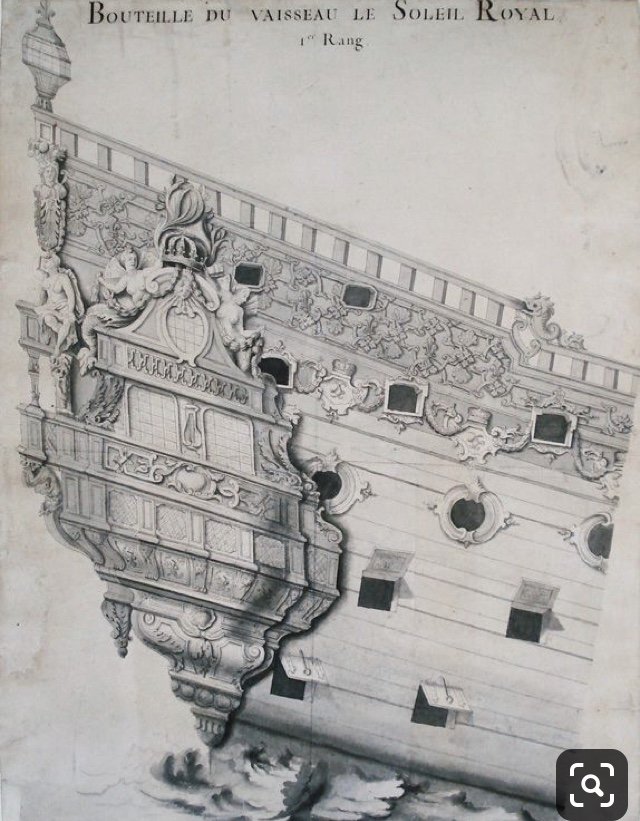

For the first time, I am able to closely examine exquisite renderings of the sets for Le Brillant, for example:

The coronation of the QG upper finishing, and the ovoid window, at the quarter deck level are closely consistent with that of the SR drawing. The same can be said for the filigree banding, along the upper balcony level, and the paneling beneath the lower gallery level of windows. These are all familiar elements of Jean Berain's oeuvre, arranged in his characteristic style.

While it is known that this set corresponds with each other, it can quickly be observed, however, that there are also strange anomalies between the stern and quarter views.

As in the SR stern drawing, at the quarter deck level, there is a shadow line that suggests an overhanging stern balcony for Le Brillant. The quarter view confirms this. There is, however, nothing in the stern view of Le Brillant to suggest that the stern counter also projects as an open, walkable balcony, and yet, that is precisely what the quarter view shows. In fact, this lower balcony seems to project even a small bit further than the upper balcony.

The trouble, here (so far as my research seems to indicate), is that by this time in 1690, the French had long abandoned walkable stern balconies at the counter level. They remained, only, as vestigial shelfs for corbels supporting open galleries above.

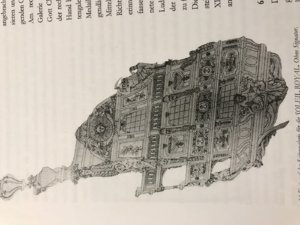

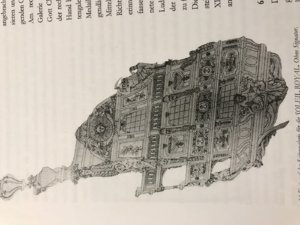

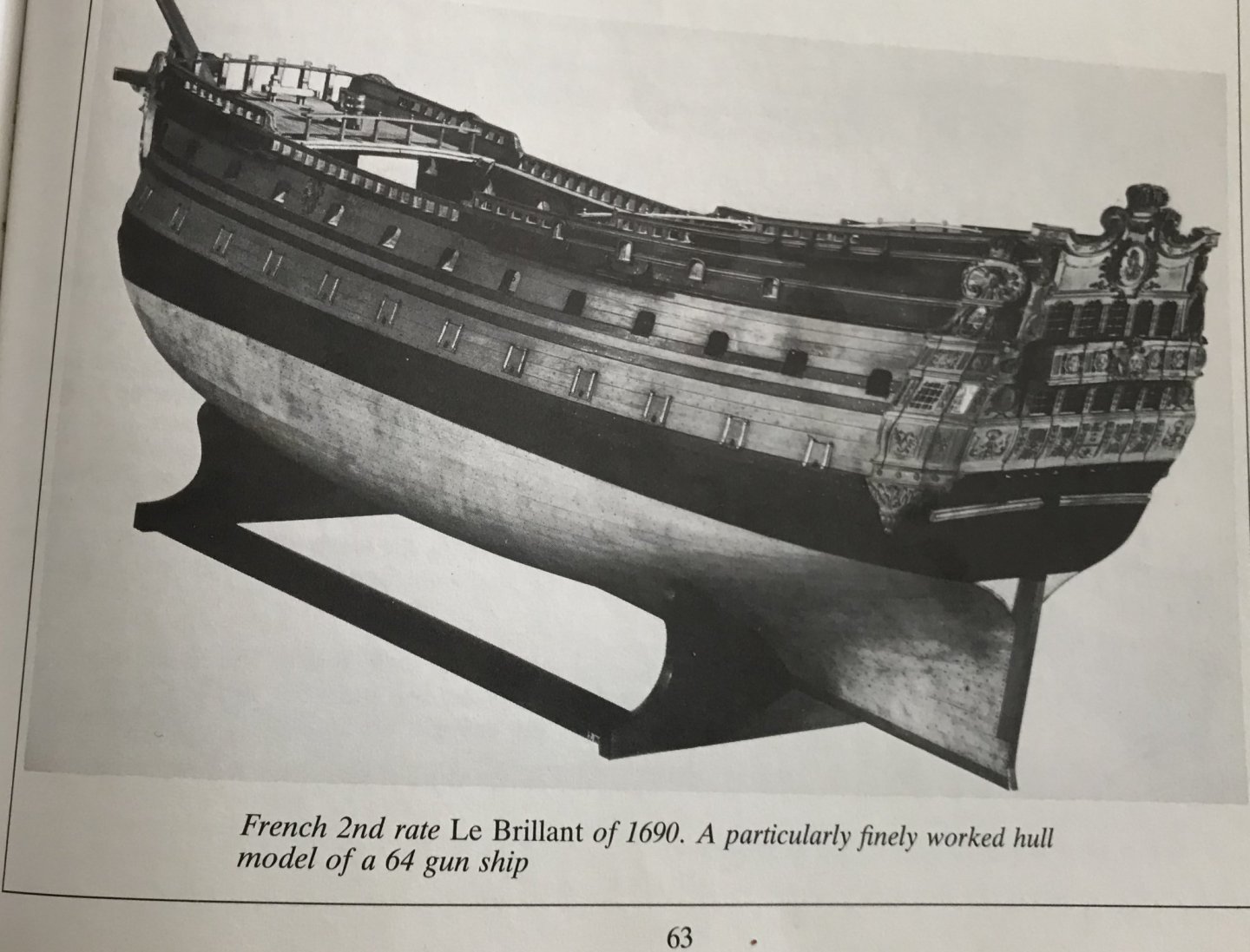

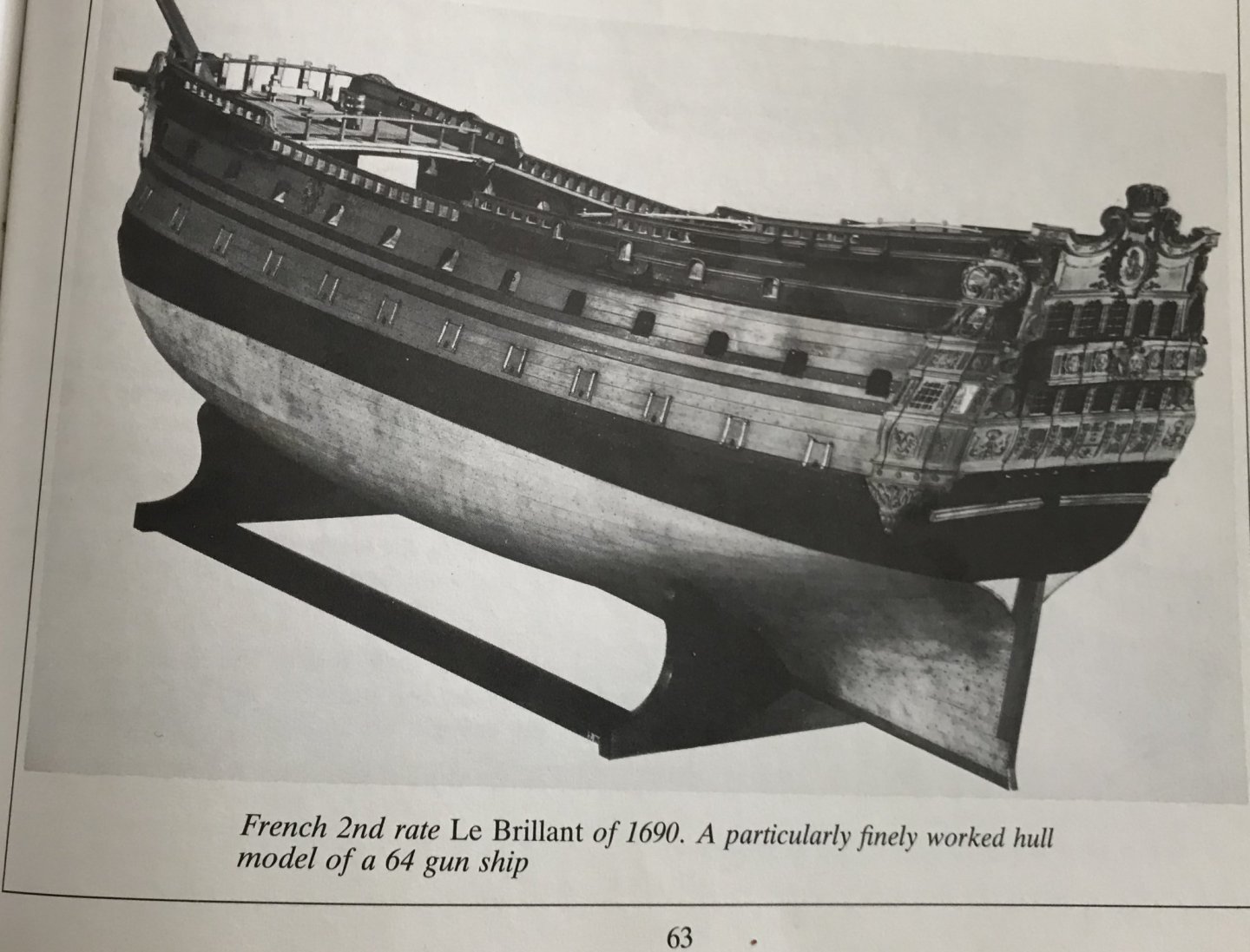

During his illustrious career as a model maker at La Musee, Tanneron also made a model of Le Brillant. His resolution of these incongruities is, I think, the correct one:

(Pic from Wolfram Zu Mondfeld)

Curiously, though, while his execution of the ornament is, for the most part, extremely close to what was drawn, for some reason he chose not to include the royal drapery swag that flanks the central medallion of Louis, on the tafferal. He also chose to replace the lambrequin tasseling above the medallion, as it was drawn by Berain, with a foliate garland. Certainly, the relative complexity of execution could not have been a deciding factor for a talent like Tanneron. He must have settled on this interpretation for other reasons.

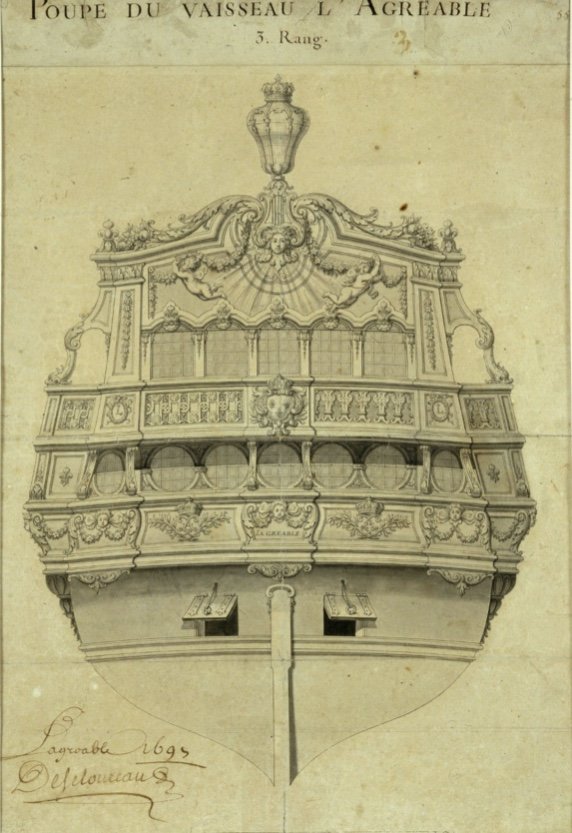

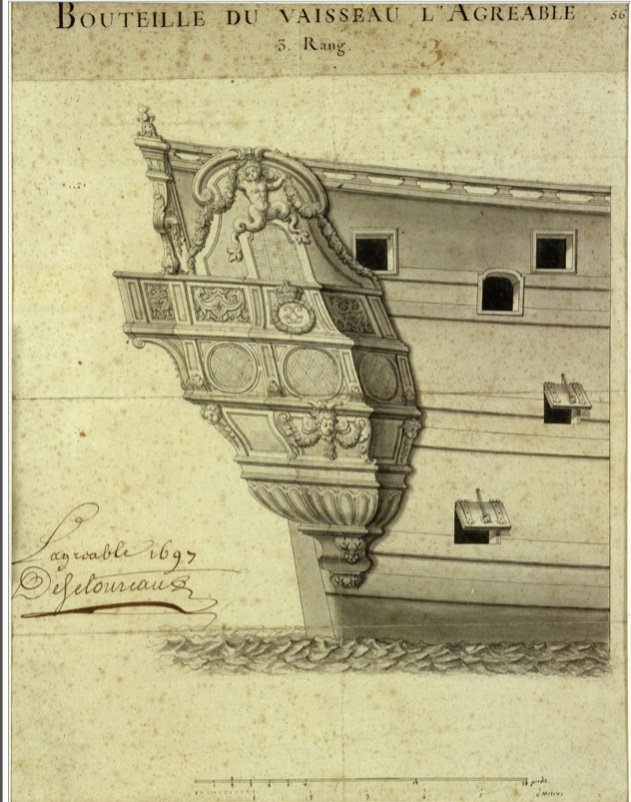

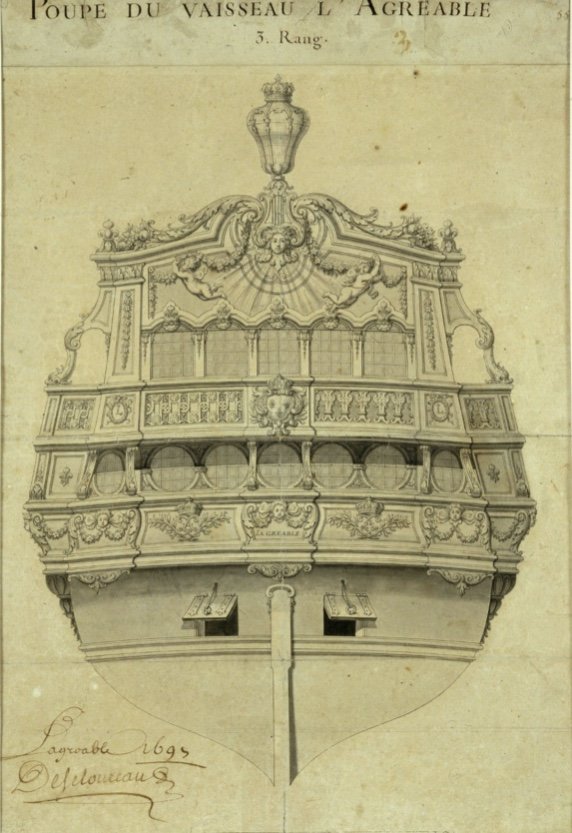

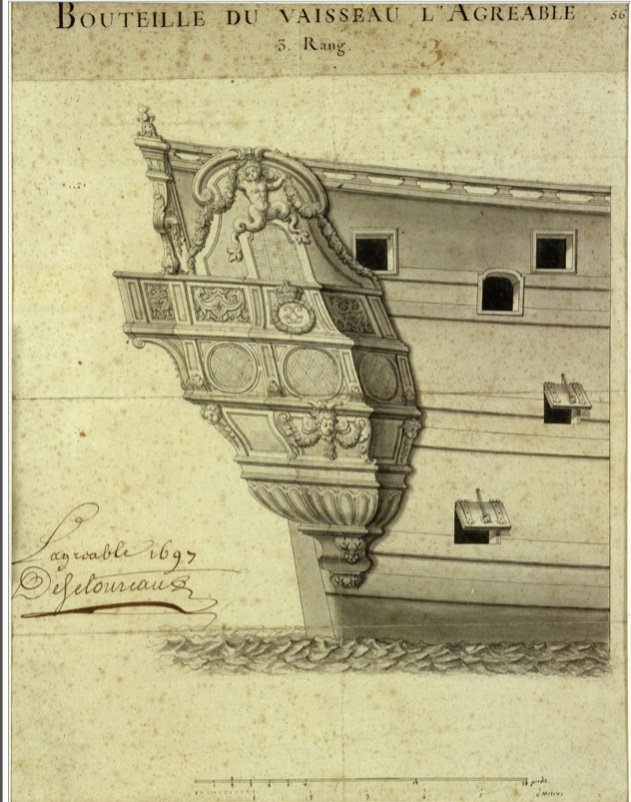

Likewise, I have found the stern and quarter views of L’Agreable to be equally fascinating. Following are studies drawn by Berain for the ship’s major refit in 1696/97:

They are signed and dated by Desclouseaux, the intendant at Brest at the time, where the work was performed. As an interesting side note, L’Agreable was originally a Toulon built ship from 1670, and she was one of the longest-lived ships of the French navy, serving faithfully until she was condemned in 1715.

It is also interesting to note that Berain drew the lower transom in the architectural manner of ships prior to the Reglement of 1672 - whereby, the wing transom that defines the widest span is located above the chase ports. This is also, notably, the case for Berain’s stern drawing of SR.

For those interested in period coloring, I also found a colored print of the stern, which gives an idea what that all may have looked like:

Anyway, what first drew me in with L’Agreable was the split-tailed triton above her quarter deck level, QG window. This figure, it seemed to me, was closely reminiscent of the First Marine stylings of Pierre Puget. Here, on Puget’s portrait of the Monarque (yes, I can hear the Royal Louis nay-sayers) are the very same sort of figures supporting the main deck quarter gallery walk:

Likewise, these figures are not un-related to the antiquated-seeming mermaid figures on the QG of Soleil Royal. Yet, here this figure appears on L’Agreable, in 1697, by the hand of Jean Berain.

So, what shall we make of that? Personally, as I have presented earlier, Jean Berain’s presentation of Soleil Royal’s stern isn’t a wholly original composition, but more an updating of the earlier execution of Puget, as first conceived by LeBrun. If it is true that some of the original ornament survived and was re-incorporated into the re-build, in 1689, why is it so far-fetched that these Puget-like mermaid figures might not also be re-imagined into Berain’s tableau?

Perhaps, in her first incarnation, split-tailed mermaid figures supported the main deck, open-walk of Soleil’s quarter galleries - as opposed to the tritons you see on the Monarque. Perhaps Berain has simply chosen to re-style them as low-reliefs that flank the upper finishing.

While none of this is certain, or even provable without a detailed and reliably attributed contemporary portrait of Soleil Royal, circa 1680, I think I have at least succeeded, with earlier posts, in demonstrating that ornamental motifs were carried over from one iteration of a ship, by a given name, to the next.

Returning to the drawings of L’Agreable, it is also of interest to me that the lower gallery windows are drawn with the antiquated diamond-hatch caming, in opposition to the cross-hatch mullions of the stern drawing - just as is illustrated in SR’s stern and quarter views. Perhaps, this diamond hatching isn’t so antiquated, after all - even in 1697.

Tanneron didn’t seem to think so. In fact, in his model of L’Agreable, he chose to represent the lower stern windows as diamond-hatched, instead of the cross-hatch that Berain drew. Why? It’s anyone’s guess:

What I really find fascinating about this Tanneron model, though, is the number of windows represented. Tanneron modeled five windows within the extension of the quarter galleries, from the ship’s sides. However, Berain’s drawing shows 7 window frames within the QG extensions!

Now, it is quite possible that the outer two frames are merely representational, and not actually glazed. They are of a more narrow silhouette. Whatever the case may be, Tanneron decided not to include them.

It could be that, with reference to whatever other sources were available to him, Tanneron decided that these two vestigial windows cluttered the presentation of the stern, since they did not also carry up to the quarter deck bank of stern windows. That would essentially amount to the same kind of artistic editing I performed with my drawing of SR’s QG, when I reduced the lower gallery tier from five to three gallery windows. I felt that the fifth, forward-most window was representational, at best.

All of these considerations, though, bring us full-circle to one of the fundamental questions about Tanneron’s model of Soleil Royal: just why did he choose to model a five-window stern, as opposed to the six-window stern that Berain drew? In truth, I can not say, but perhaps Tanneron demonstrated an artistic preference, there, for a lesser profusion of windows. Along that line of reasoning, he certainly simplified the tasseled lambrequin carving that Berain drew for the lower, false gallery.

Whatever the truths may be, I think it is clear that there is precedent for divergence in the model makers’ art when interpreting these primary source drawings - even when there is a high degree of congruence between stern and quarter views.

Until better sources emerge (and I’m always looking), I’m going to stick with this as my operating theory of the epoch.

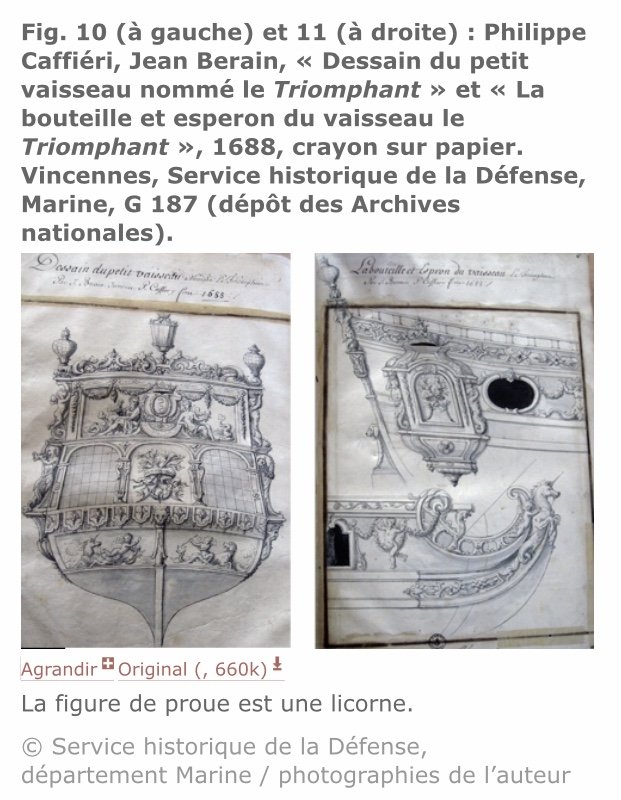

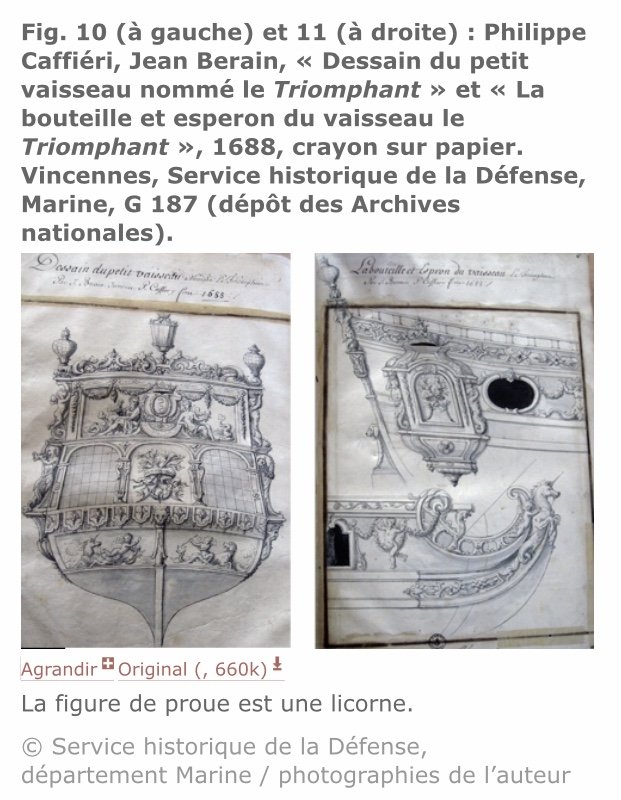

And just because they are interesting, here are a few drawings for the ornamentation of a Versailles fountain barge (I believe that’s what it represents) that Berain collaborated with Philippe Caffieri to create in 1688:

It is, in my view, a mixture of old and new styles, with a bulwark frieze that echoes that of Soleil Royal.

Edited September 10, 2019 by Hubac's Historian

__

Now that I have completed my light re-design of the Berain/Vary quarter galleries, I also had time to reflect upon some of the questions and criticisms that scholars levy against the likelihood that they are the rightful companion to the known Berain stern drawing, for this time that I have targeted in 1689.

In correspondence I have held with these individuals, they cite anomalies in the scale and execution of this drawing.

The lower false stern balcony, for example, is grossly exaggerated. They also mention that the relative proportion of the windows at each of the three levels does not neatly correspond with the relative proportions shown on the stern drawing. If that weren’t enough, the diamond-hatch, leaded cames of the lower gallery windows is of the antiquated (First Marine) style, and it does not match the cross-hatched mullions on the stern drawing. I agree that these anomalies are hard to jibe with what is clearly an exquisitely rendered stern drawing, where not one line or detail seems out of proportion or place.

All of these individuals point toward the missing elephantine head-dress of the figure of Africa; has Berain suddenly forgotten that what he shows from the stern perspective must also appear in the quarter view, they wonder? I wonder that too.

Not lastly, but also notably, these individuals point to the mermaid figures as being wholly inconsistent with the stern allegory, and more likely a relic of the earlier First Marine style of ornamentation. Again, I find it hard to argue against these observations.

In fact, I will probably never be able to definitively say that this QG rendering is the hand of Berain, because as these men also point out, it is not archived as a set with the stern drawing. Nevertheless, these considerations won’t stop me from attempting to bolster my central argument - that these stern and quarter drawings do correspond.

And so, ever remaining consistent with my approach to research, I am always studying SR’s better documented contemporaries and near contemporaries in search of structural and ornamental patterns of consistency.

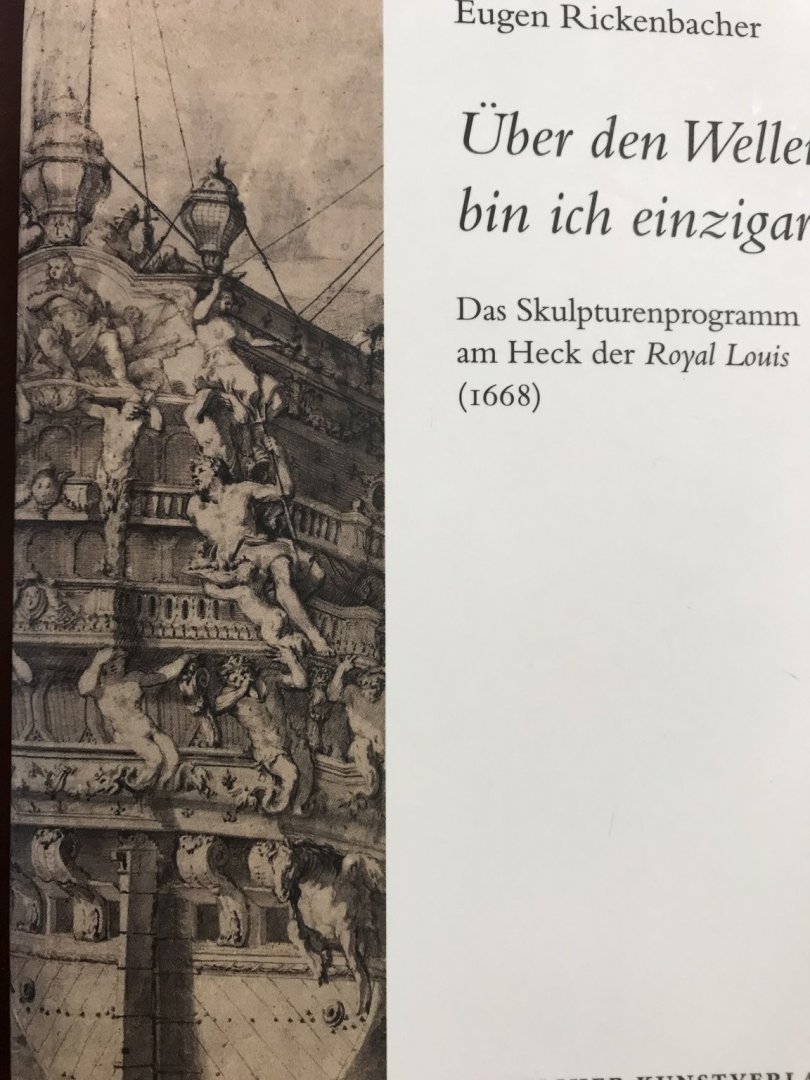

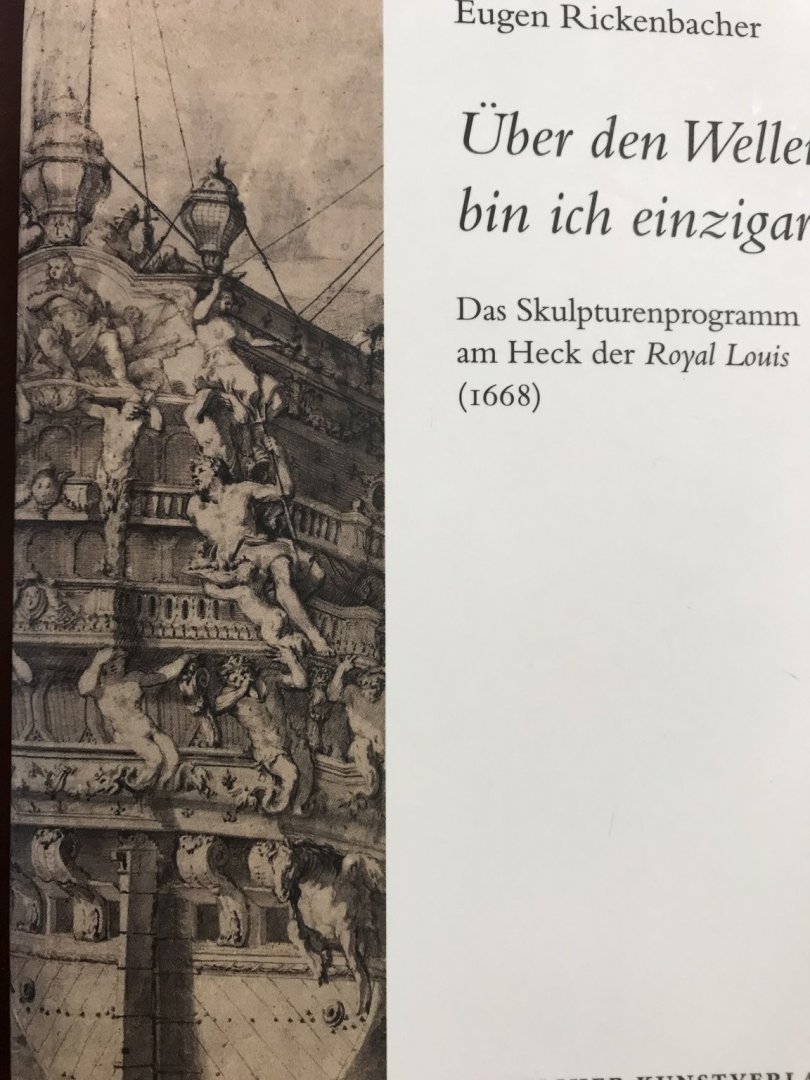

This book, Floating Baroque (thanks again to Heinrich) has been an invaluable resource because it provides me with archival quality reproductions of ornamental sets that are known to correspond with each other, from a specific time, and originating at the hand of Jean Berain.

For the first time, I am able to closely examine exquisite renderings of the sets for Le Brillant, for example:

The coronation of the QG upper finishing, and the ovoid window, at the quarter deck level are closely consistent with that of the SR drawing. The same can be said for the filigree banding, along the upper balcony level, and the paneling beneath the lower gallery level of windows. These are all familiar elements of Jean Berain's oeuvre, arranged in his characteristic style.

While it is known that this set corresponds with each other, it can quickly be observed, however, that there are also strange anomalies between the stern and quarter views.

As in the SR stern drawing, at the quarter deck level, there is a shadow line that suggests an overhanging stern balcony for Le Brillant. The quarter view confirms this. There is, however, nothing in the stern view of Le Brillant to suggest that the stern counter also projects as an open, walkable balcony, and yet, that is precisely what the quarter view shows. In fact, this lower balcony seems to project even a small bit further than the upper balcony.

The trouble, here (so far as my research seems to indicate), is that by this time in 1690, the French had long abandoned walkable stern balconies at the counter level. They remained, only, as vestigial shelfs for corbels supporting open galleries above.

During his illustrious career as a model maker at La Musee, Tanneron also made a model of Le Brillant. His resolution of these incongruities is, I think, the correct one:

(Pic from Wolfram Zu Mondfeld)

Curiously, though, while his execution of the ornament is, for the most part, extremely close to what was drawn, for some reason he chose not to include the royal drapery swag that flanks the central medallion of Louis, on the tafferal. He also chose to replace the lambrequin tasseling above the medallion, as it was drawn by Berain, with a foliate garland. Certainly, the relative complexity of execution could not have been a deciding factor for a talent like Tanneron. He must have settled on this interpretation for other reasons.

Likewise, I have found the stern and quarter views of L’Agreable to be equally fascinating. Following are studies drawn by Berain for the ship’s major refit in 1696/97:

They are signed and dated by Desclouseaux, the intendant at Brest at the time, where the work was performed. As an interesting side note, L’Agreable was originally a Toulon built ship from 1670, and she was one of the longest-lived ships of the French navy, serving faithfully until she was condemned in 1715.

It is also interesting to note that Berain drew the lower transom in the architectural manner of ships prior to the Reglement of 1672 - whereby, the wing transom that defines the widest span is located above the chase ports. This is also, notably, the case for Berain’s stern drawing of SR.

For those interested in period coloring, I also found a colored print of the stern, which gives an idea what that all may have looked like:

Anyway, what first drew me in with L’Agreable was the split-tailed triton above her quarter deck level, QG window. This figure, it seemed to me, was closely reminiscent of the First Marine stylings of Pierre Puget. Here, on Puget’s portrait of the Monarque (yes, I can hear the Royal Louis nay-sayers) are the very same sort of figures supporting the main deck quarter gallery walk:

Likewise, these figures are not un-related to the antiquated-seeming mermaid figures on the QG of Soleil Royal. Yet, here this figure appears on L’Agreable, in 1697, by the hand of Jean Berain.

So, what shall we make of that? Personally, as I have presented earlier, Jean Berain’s presentation of Soleil Royal’s stern isn’t a wholly original composition, but more an updating of the earlier execution of Puget, as first conceived by LeBrun. If it is true that some of the original ornament survived and was re-incorporated into the re-build, in 1689, why is it so far-fetched that these Puget-like mermaid figures might not also be re-imagined into Berain’s tableau?

Perhaps, in her first incarnation, split-tailed mermaid figures supported the main deck, open-walk of Soleil’s quarter galleries - as opposed to the tritons you see on the Monarque. Perhaps Berain has simply chosen to re-style them as low-reliefs that flank the upper finishing.

While none of this is certain, or even provable without a detailed and reliably attributed contemporary portrait of Soleil Royal, circa 1680, I think I have at least succeeded, with earlier posts, in demonstrating that ornamental motifs were carried over from one iteration of a ship, by a given name, to the next.

Returning to the drawings of L’Agreable, it is also of interest to me that the lower gallery windows are drawn with the antiquated diamond-hatch caming, in opposition to the cross-hatch mullions of the stern drawing - just as is illustrated in SR’s stern and quarter views. Perhaps, this diamond hatching isn’t so antiquated, after all - even in 1697.

Tanneron didn’t seem to think so. In fact, in his model of L’Agreable, he chose to represent the lower stern windows as diamond-hatched, instead of the cross-hatch that Berain drew. Why? It’s anyone’s guess:

What I really find fascinating about this Tanneron model, though, is the number of windows represented. Tanneron modeled five windows within the extension of the quarter galleries, from the ship’s sides. However, Berain’s drawing shows 7 window frames within the QG extensions!

Now, it is quite possible that the outer two frames are merely representational, and not actually glazed. They are of a more narrow silhouette. Whatever the case may be, Tanneron decided not to include them.

It could be that, with reference to whatever other sources were available to him, Tanneron decided that these two vestigial windows cluttered the presentation of the stern, since they did not also carry up to the quarter deck bank of stern windows. That would essentially amount to the same kind of artistic editing I performed with my drawing of SR’s QG, when I reduced the lower gallery tier from five to three gallery windows. I felt that the fifth, forward-most window was representational, at best.

All of these considerations, though, bring us full-circle to one of the fundamental questions about Tanneron’s model of Soleil Royal: just why did he choose to model a five-window stern, as opposed to the six-window stern that Berain drew? In truth, I can not say, but perhaps Tanneron demonstrated an artistic preference, there, for a lesser profusion of windows. Along that line of reasoning, he certainly simplified the tasseled lambrequin carving that Berain drew for the lower, false gallery.

Whatever the truths may be, I think it is clear that there is precedent for divergence in the model makers’ art when interpreting these primary source drawings - even when there is a high degree of congruence between stern and quarter views.

Until better sources emerge (and I’m always looking), I’m going to stick with this as my operating theory of the epoch.

And just because they are interesting, here are a few drawings for the ornamentation of a Versailles fountain barge (I believe that’s what it represents) that Berain collaborated with Philippe Caffieri to create in 1688:

It is, in my view, a mixture of old and new styles, with a bulwark frieze that echoes that of Soleil Royal.

Edited September 10, 2019 by Hubac's Historian

One last addendum to the post above - it is my observation, among these catalogued sets of stern and quarter drawings - that Berain did not include any of the details of the quarter galleries, in his stern view - not even, if, say, the amortisement would be visible through the open archway to the quarters.

Another glaring example of this is that you never see any reference of the QG lower finishing in the stern drawing. You often will see the waste pipe, terminating in some form of foliate rosette, but only because it resides within the plane of the stern.

Take a closer look at the sets, above - particularly Le Brillant - and you will see what I mean. I think this drawing convention was intended to make the drawings appear less cluttered. If taken literally, though, these discrepancies can be quite confusing.

Puget drew every last detail, as though you were looking at a photograph.

Another glaring example of this is that you never see any reference of the QG lower finishing in the stern drawing. You often will see the waste pipe, terminating in some form of foliate rosette, but only because it resides within the plane of the stern.

Take a closer look at the sets, above - particularly Le Brillant - and you will see what I mean. I think this drawing convention was intended to make the drawings appear less cluttered. If taken literally, though, these discrepancies can be quite confusing.

Puget drew every last detail, as though you were looking at a photograph.

Last edited:

Detail details details, you do have considerable research behind this project.

Interesting for a future scratch build as I don't like any of the avalable kit drawings available for this vessel.

Interesting for a future scratch build as I don't like any of the avalable kit drawings available for this vessel.

Well, Maarten, that was partly the intent of the build-log. I wanted to create a one-stop repository for all of this fragmentary and related imagery, so that I could attempt, over time, to place it within some kind of coherent context. Assumptions I made, early on, have proved to be wrong. There have been portraits and vessels that I have mis-attributed (like many others before me), only to discover what they really are. The single most valuable addition to my library has been Winfield and Roberts’s, French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626-1786.

Another invaluable resource is Andrew Peters’s Ship Decoration 1630-1780.

The result of all of this is that I have already written large passages of what will some day be my conjectural monograph:

The Gilded Ghost

A Forensic Reconstruction of Laurent Hubac’s Soleil Royal of 1670

By Marc LaGuardia

Right now - there are at least two modelers who have re-constructed highly plausible hull forms for first-rates of this period:

Marc Yeu’s Soleil Royal in 1/72 (think that’s his scale)

Tony Devroude’s Dauphine Royal of 1668

The latter is a fully framed model, and the architecture is truly excellent and representative of the high-raking sheer of these early ships of the First Marine.

Marc Yeu’s model will soon become the new benchmark for all future builds of Soleil Royal; his achievement as a self-taught woodworker and modeler is absolutely staggering, IMO.

Another invaluable resource is Andrew Peters’s Ship Decoration 1630-1780.

The result of all of this is that I have already written large passages of what will some day be my conjectural monograph:

The Gilded Ghost

A Forensic Reconstruction of Laurent Hubac’s Soleil Royal of 1670

By Marc LaGuardia

Right now - there are at least two modelers who have re-constructed highly plausible hull forms for first-rates of this period:

Marc Yeu’s Soleil Royal in 1/72 (think that’s his scale)

Tony Devroude’s Dauphine Royal of 1668

The latter is a fully framed model, and the architecture is truly excellent and representative of the high-raking sheer of these early ships of the First Marine.

Marc Yeu’s model will soon become the new benchmark for all future builds of Soleil Royal; his achievement as a self-taught woodworker and modeler is absolutely staggering, IMO.

Last edited:

Marc

I agree with your decision regarding the glazing.This is the way I would portray her.

Not to detract from your log,I have to ask,do you refer to Nino Pizzichemi's model?I used to converse with him some years ago but he is now immersed in other hobbies and to my knowledge,no longer building models.The sculpture was done in modelling clay and the lanterns cast in clear resin.

Kind Regards

Nigel

I agree with your decision regarding the glazing.This is the way I would portray her.

Not to detract from your log,I have to ask,do you refer to Nino Pizzichemi's model?I used to converse with him some years ago but he is now immersed in other hobbies and to my knowledge,no longer building models.The sculpture was done in modelling clay and the lanterns cast in clear resin.

Kind Regards

Nigel

Yes, Nigel - this is the model! Are there more pictures you can post of her? That would he a shame, if a talent like that were no longer building ships.

Marc,I will see what I can find,I am still friends with Nino on Facebook.

Kind Regards

Nigel

Kind Regards

Nigel