I continue to distract myself from the pandemic and my isolation from my family with work on the model.

As you know, I’ve been experimenting with Liquitex Extra Heavy Gel medium. At first, I was trying to brush it in place, but I lack a fine enough brush, and all art stores are closed for the foreseeable future.

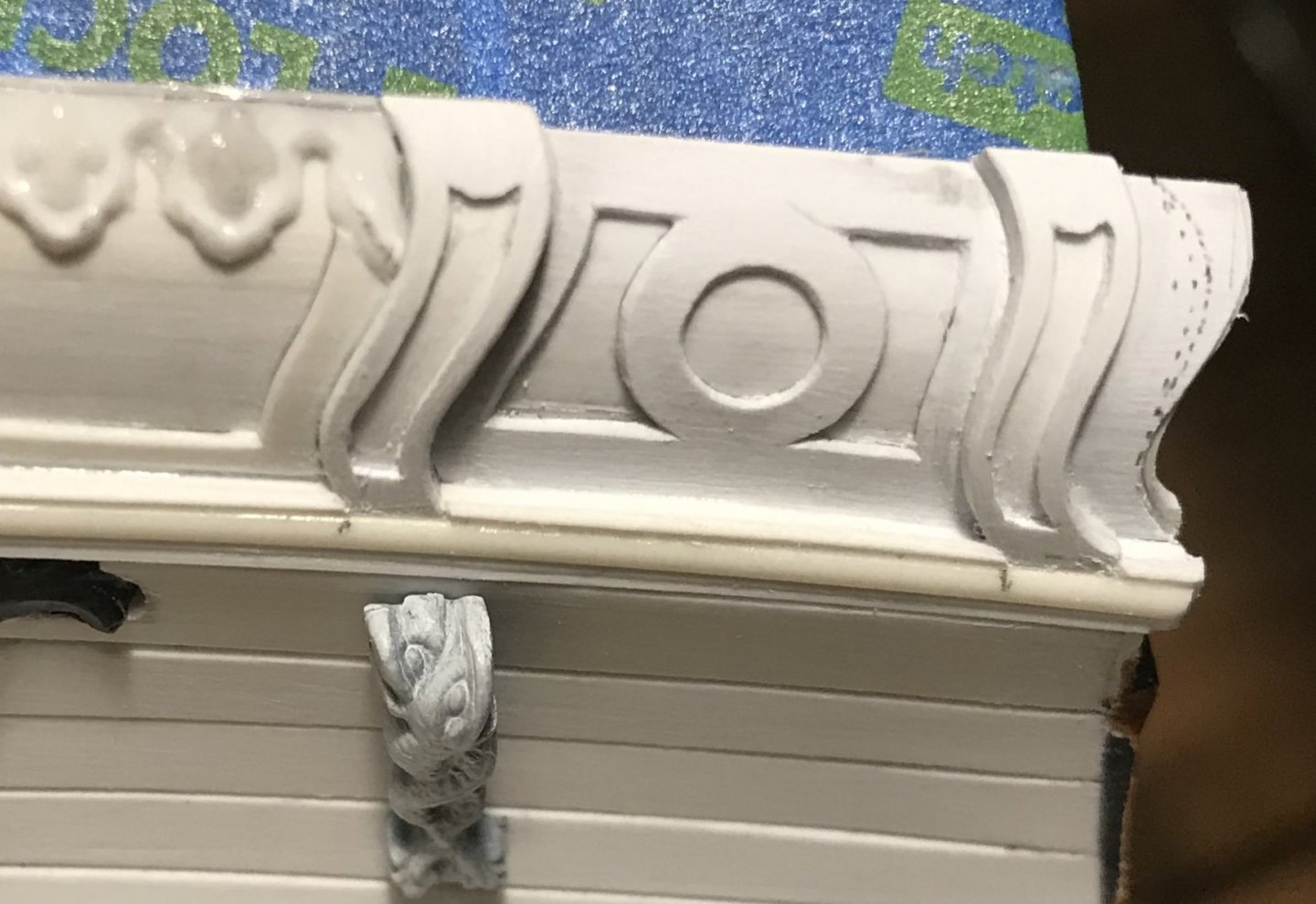

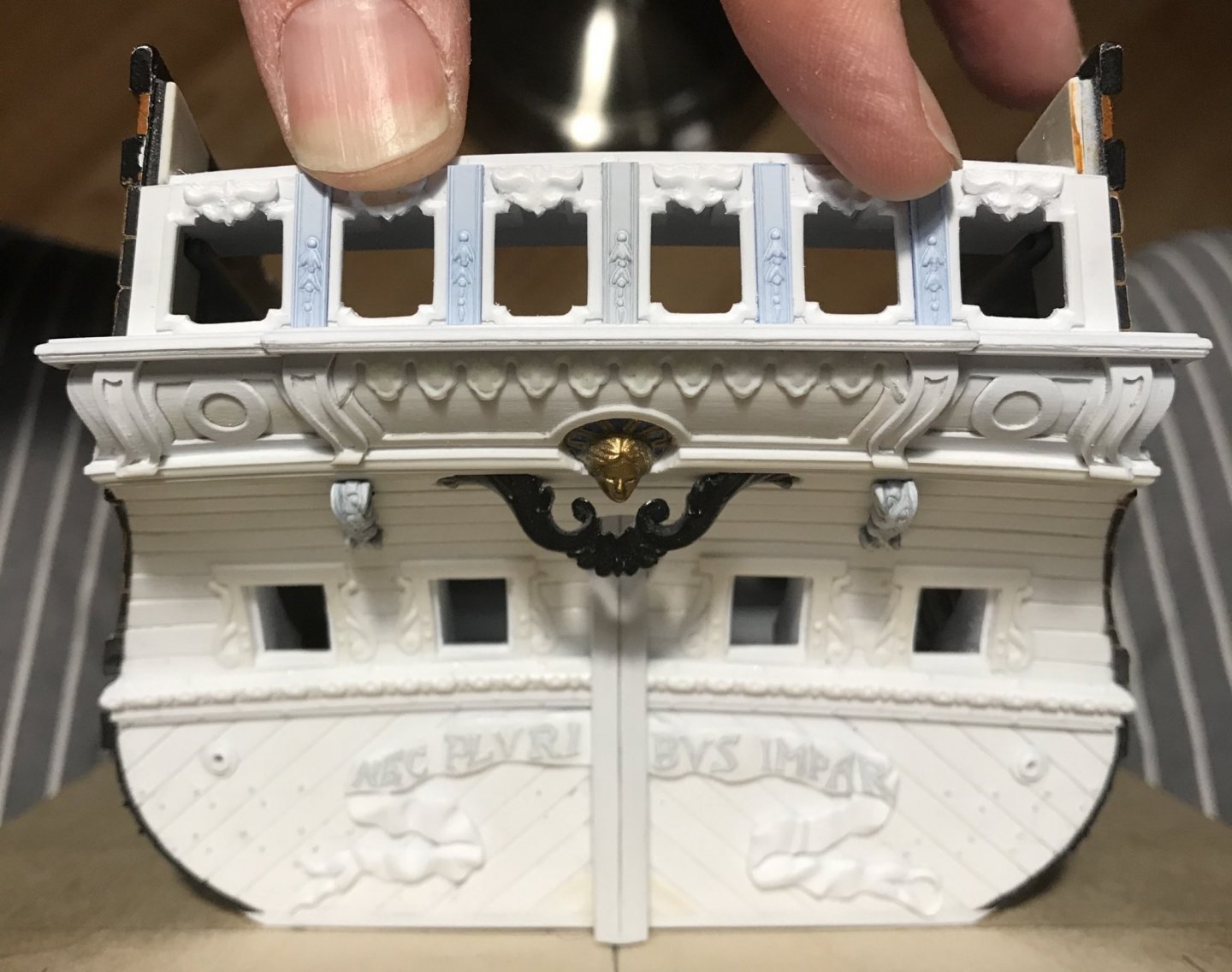

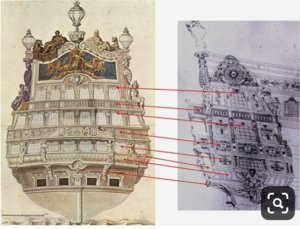

But then, I happened upon this build video on YouTube, and I was fascinated by his use of common toothpicks to paint in the fine statuary on this Revell 1:150 kit of the Vasa:

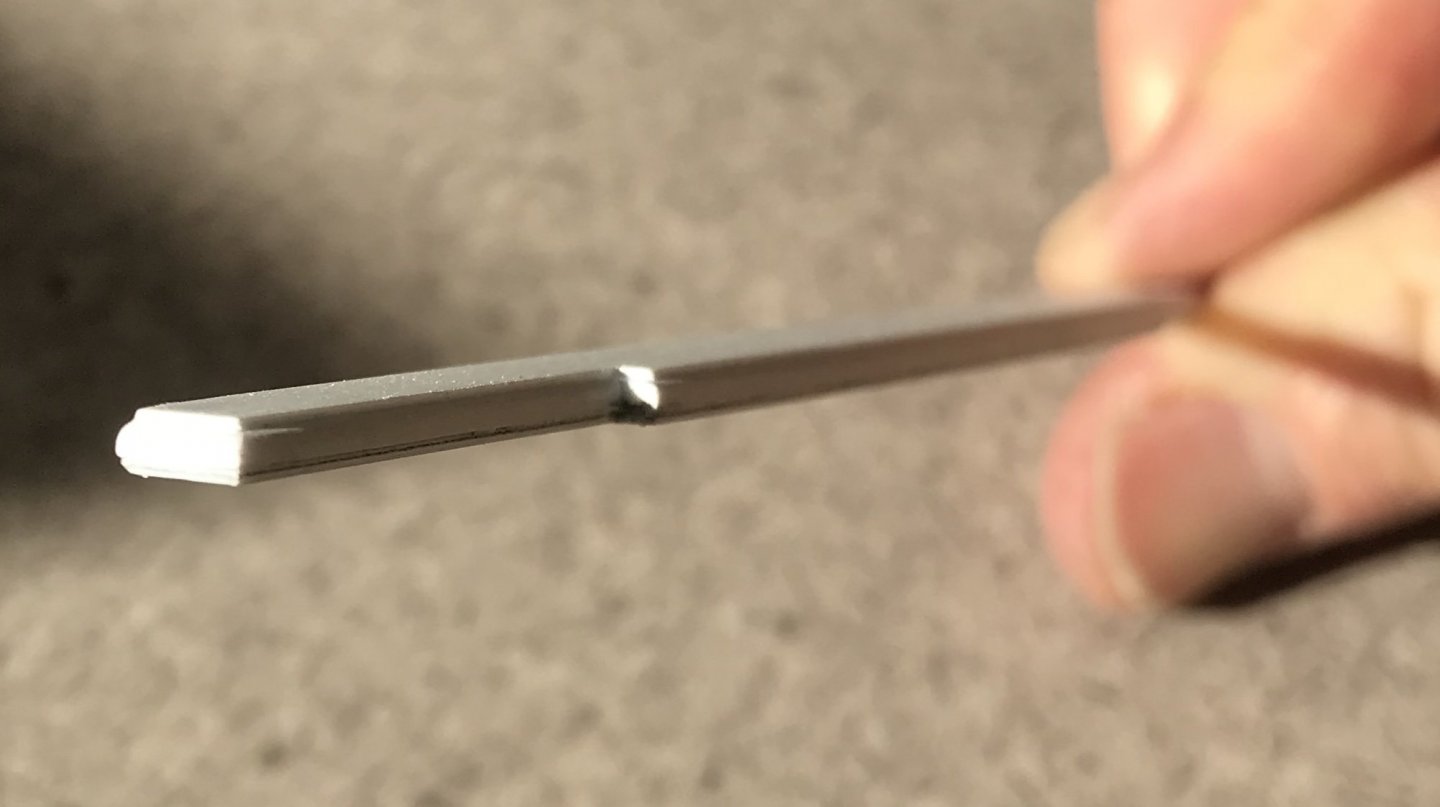

This inspired me to sharpen the end of a toothpick and try that as an application method.

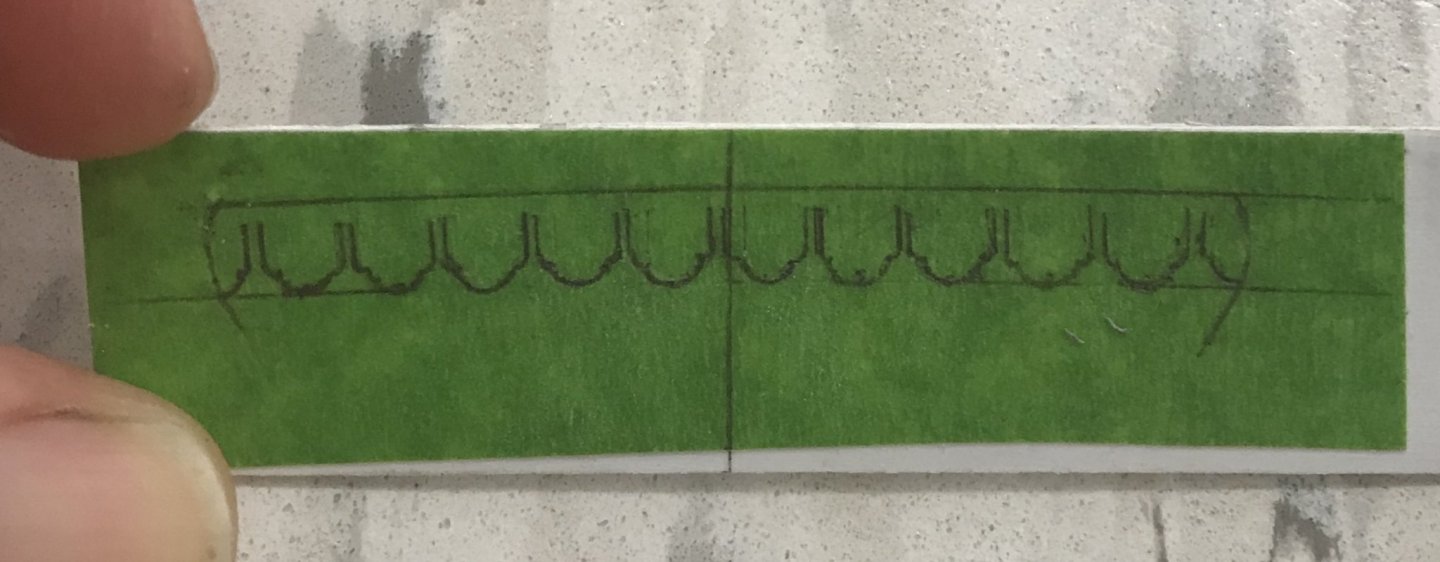

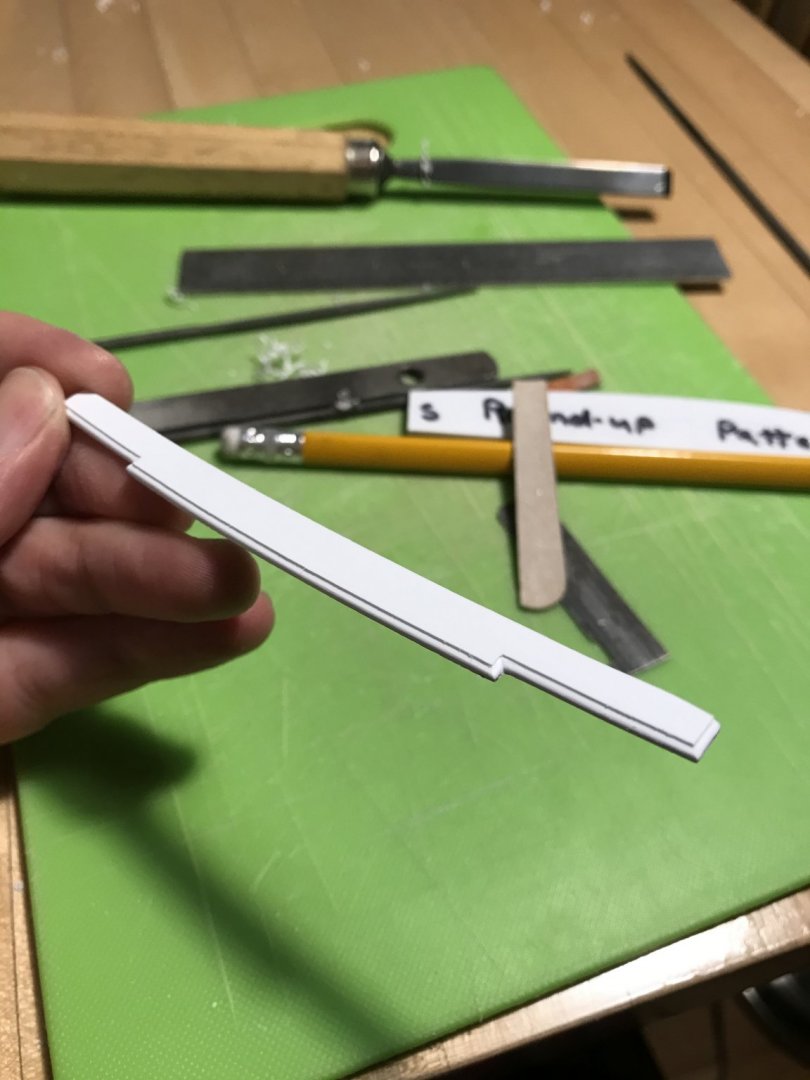

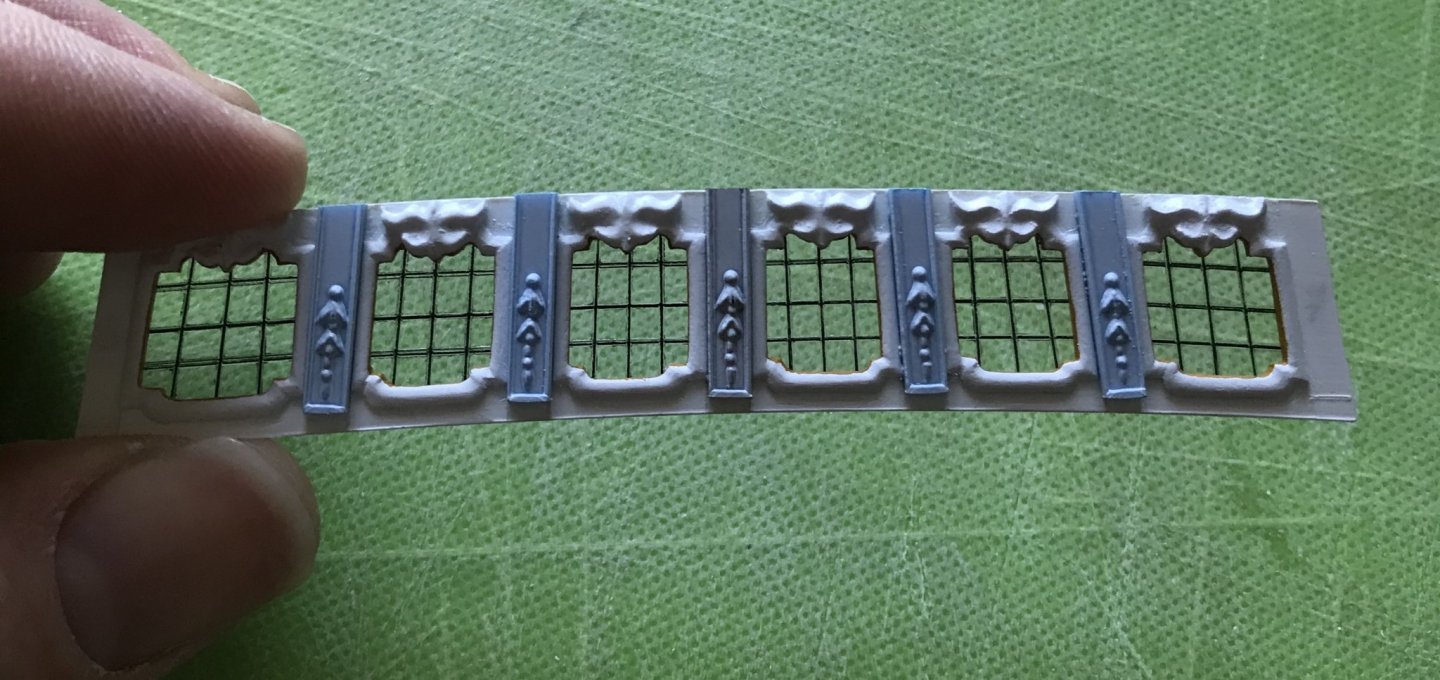

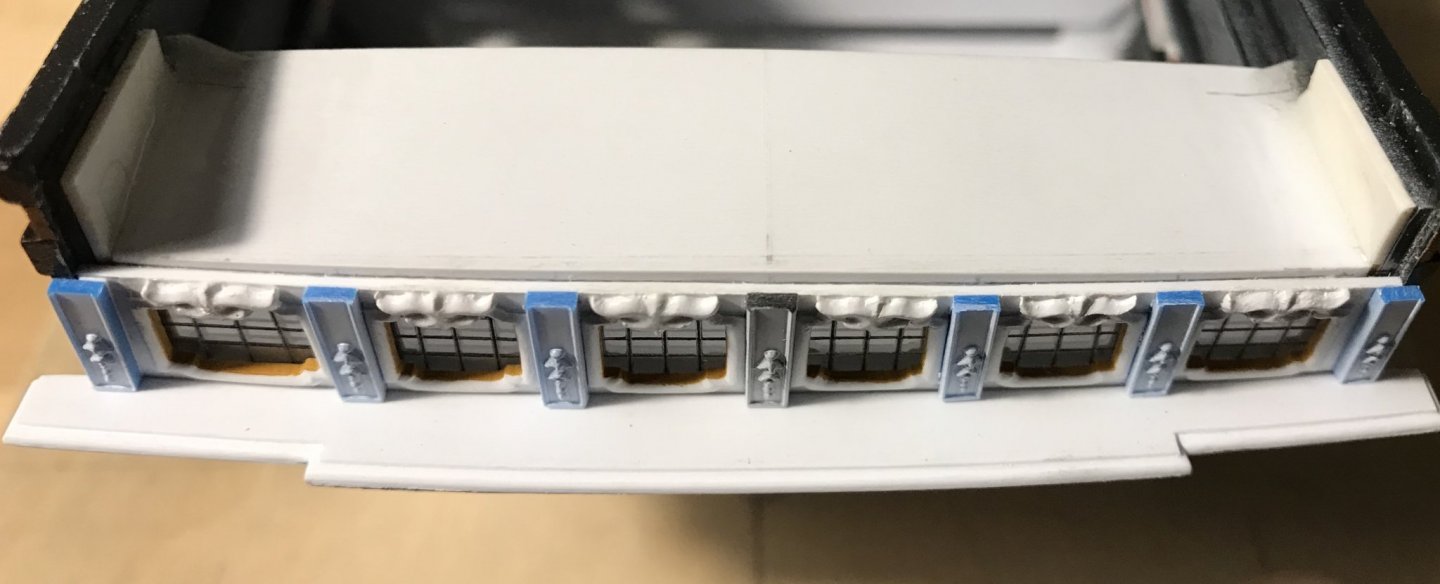

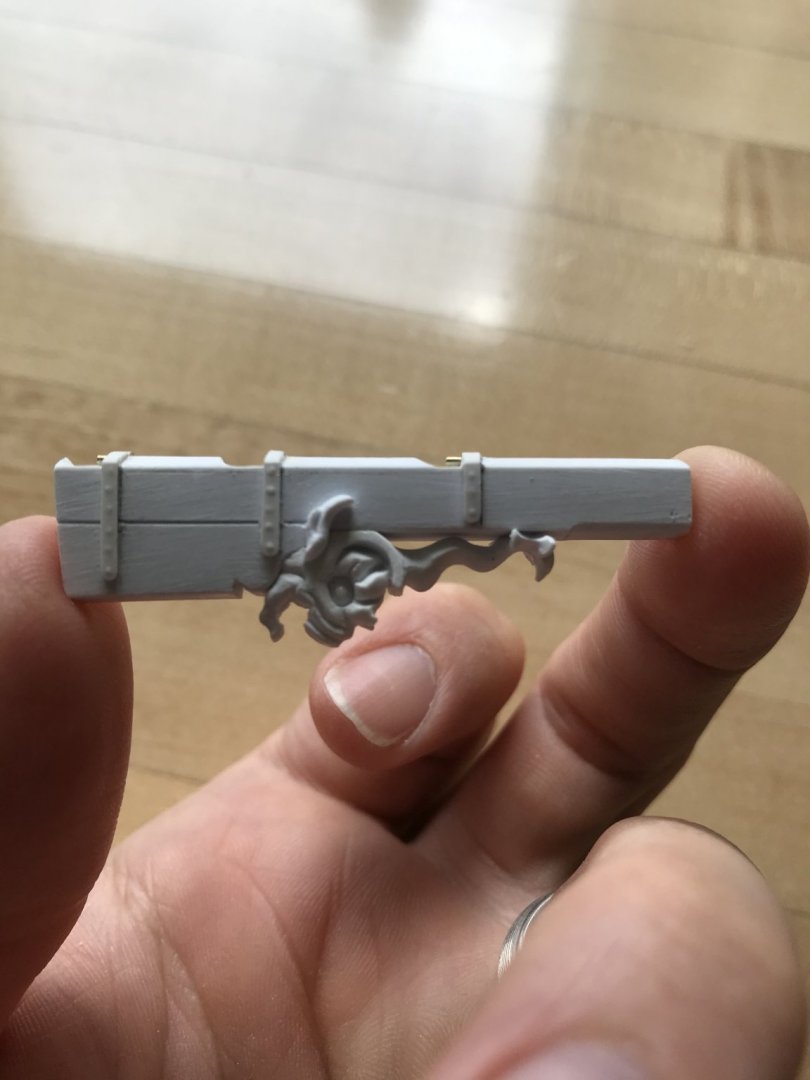

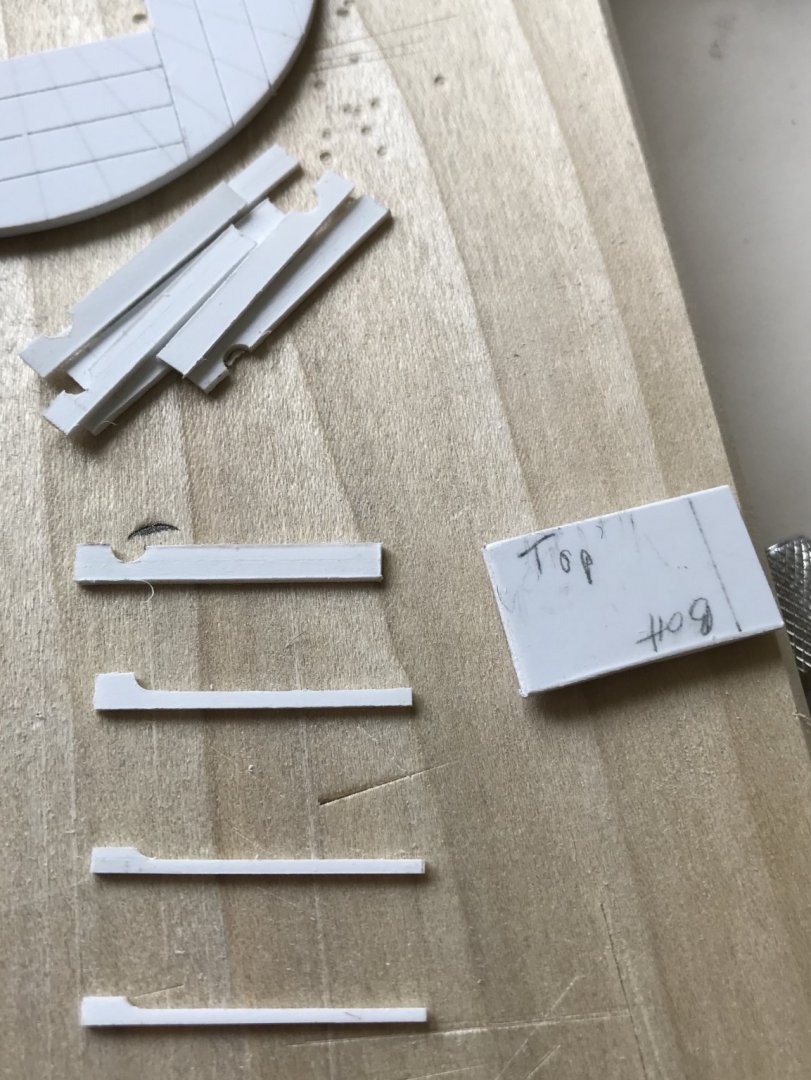

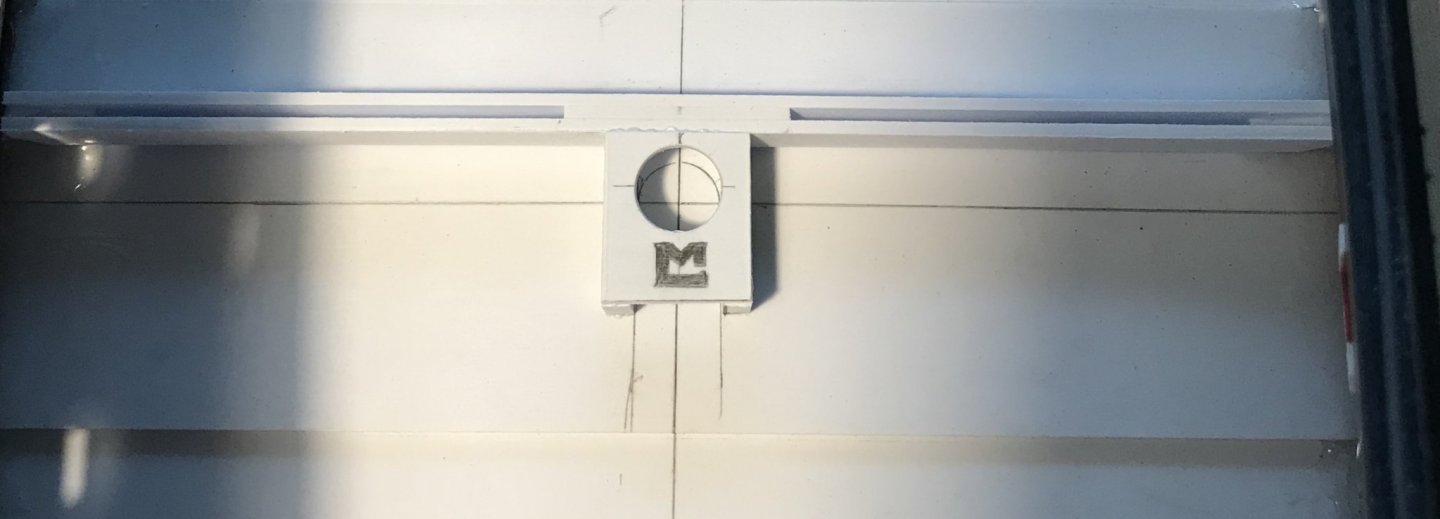

First, I made up a piece of scrap that gave me the spacing I need for the tasseling:

The Liquitex is an interesting product. It has the consistency of thick moisturizing cream, and I found that the dime-sized dollops that I would dole-out onto a paper towel, would skin-over within a few minutes. It was necessary to “stir” the dollop every few minutes, in order to apply the product with ease. After a few stirrings, a new dollop would be necessary, but there is an entire lifetime of product in one small jar, so it is not a big deal.

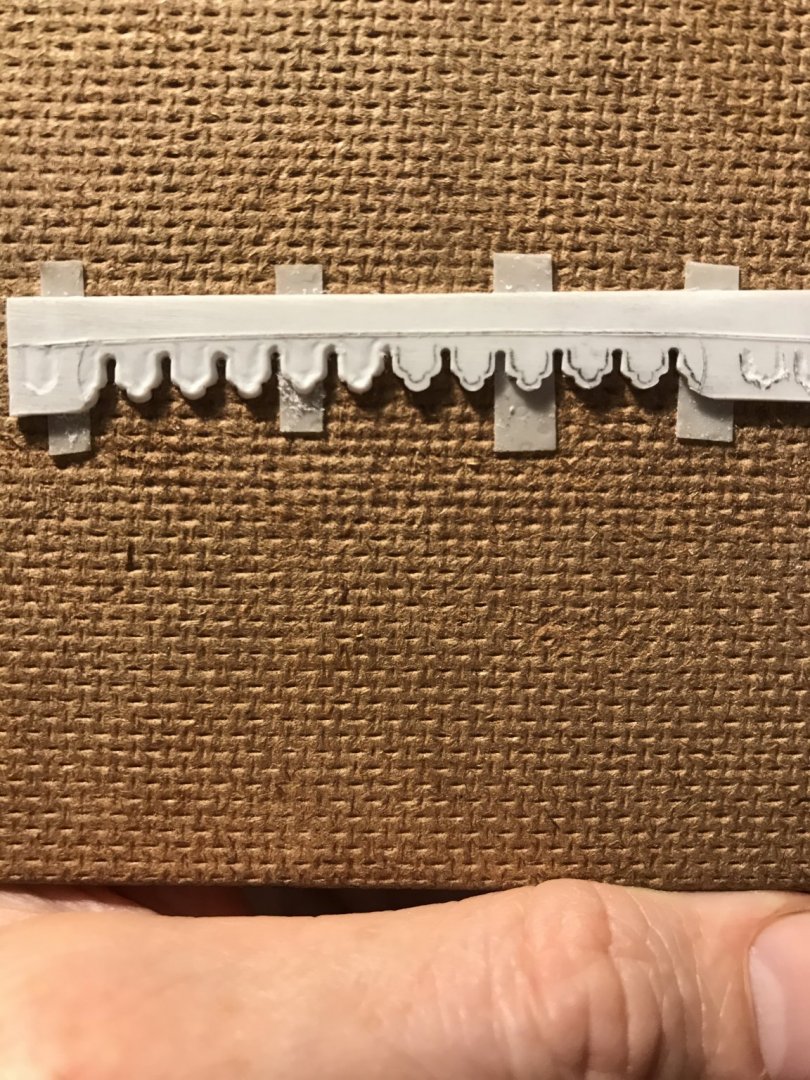

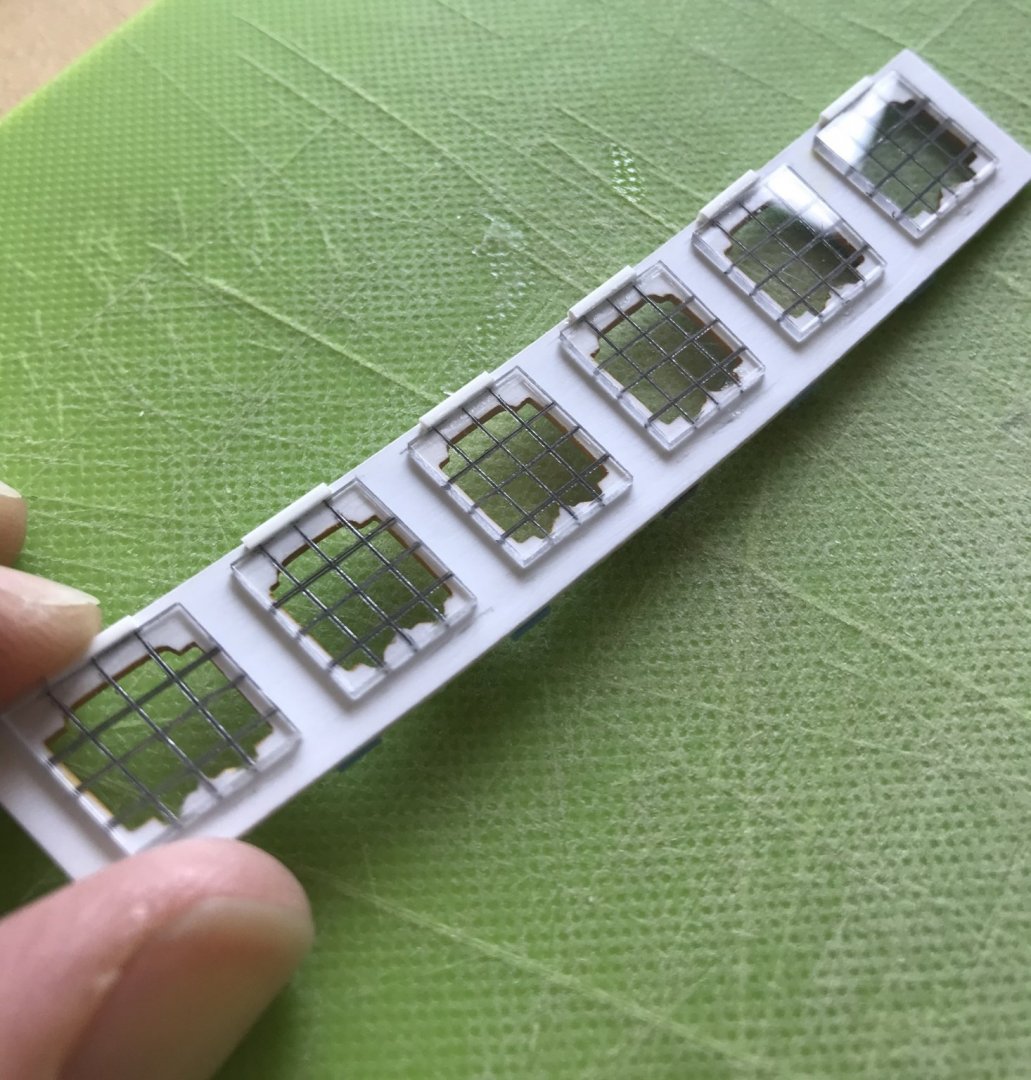

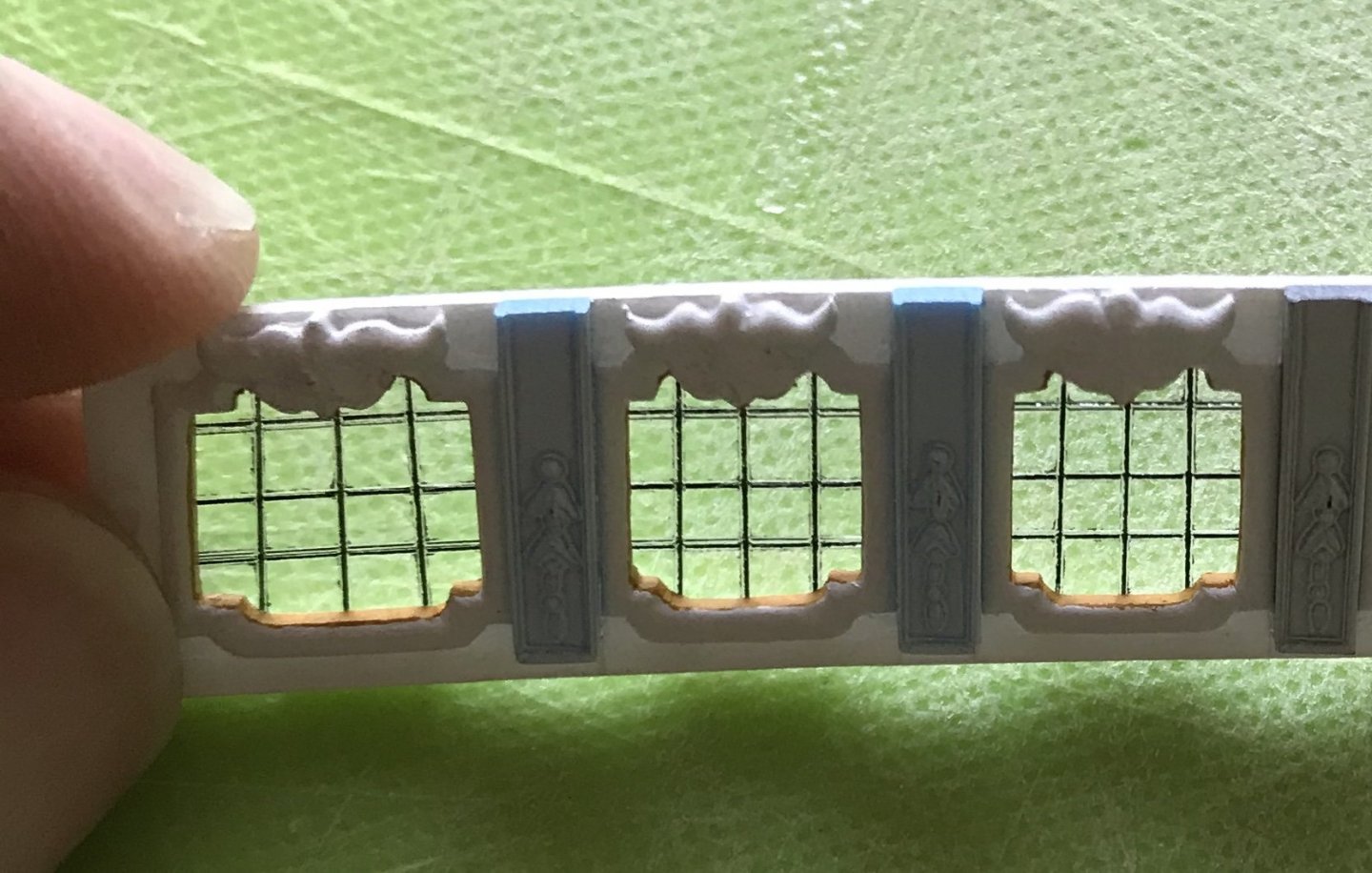

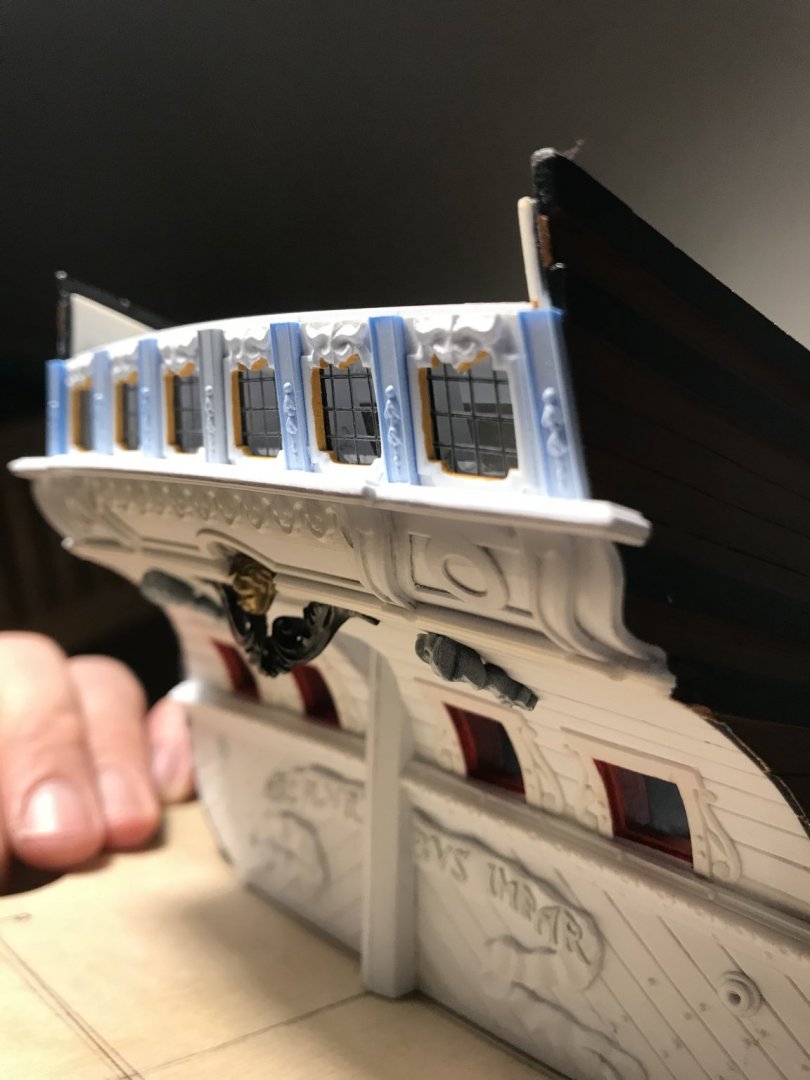

What I was aiming for was a sort of Hershey Kiss, triangular shape. I found that three applications gave enough depth of relief that I will not have trouble picking the tassels out with a brush, or maybe a toothpick

I found that the cured gel medium could be scraped away from my sample strip, without too much effort, using your finger nail. The counter area on the model, however, is more coarsely sanded and should provide a better mechanical bond. That being said, I will probably paint over the finished tassels with thin cyano, just for the added insurance that provides. I am sure the eventual paint film would he sufficient, but this cyano treatment is fast becoming part of my process.

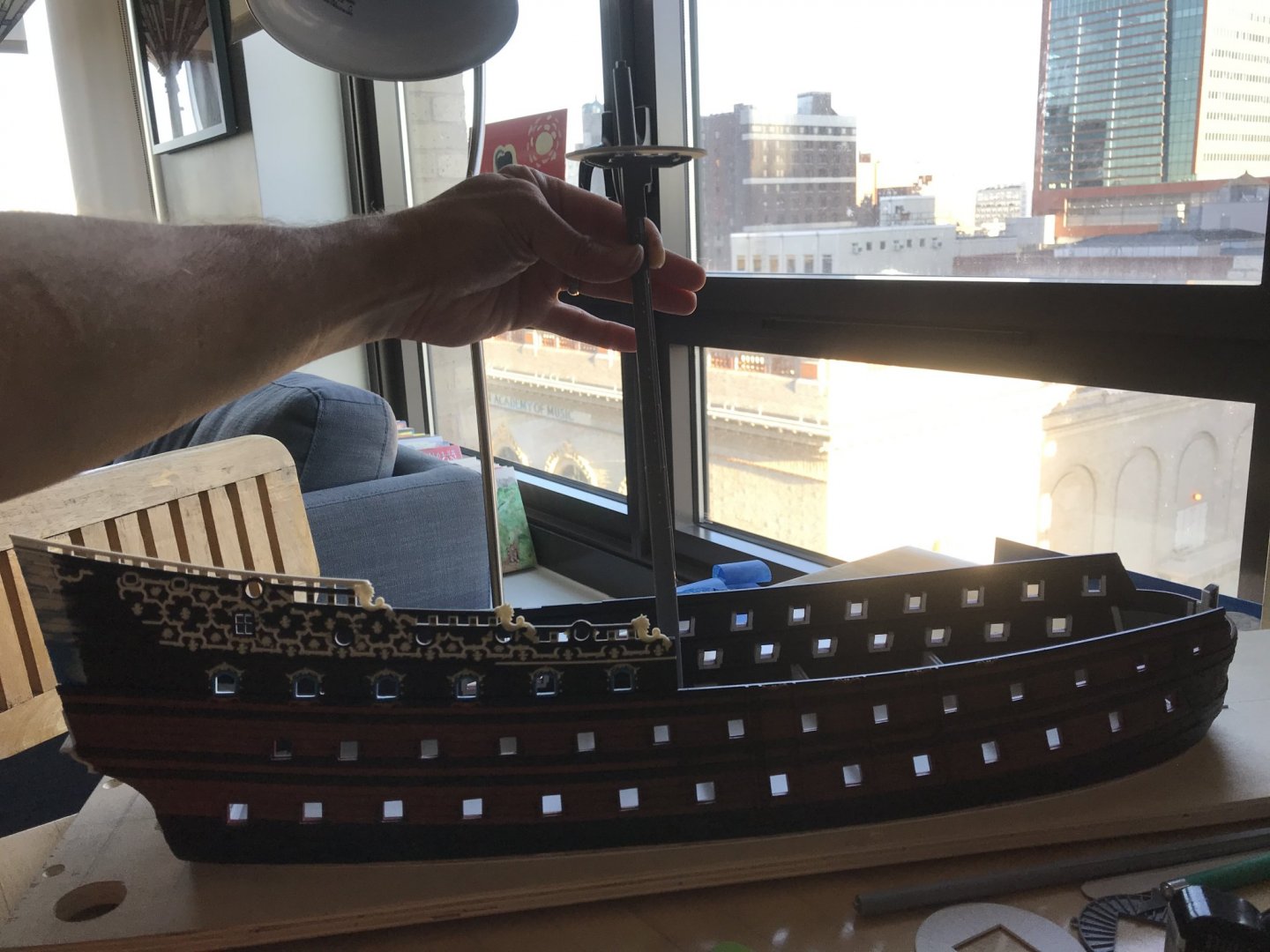

So, at this stage, I became free to focus on building up the lower gun deck. Before I can do that, I needed to cut the lower main mast to height, and create a boxed footing for the mast.

I also wanted to mock up, and then make the larger diameter main top, in order to get a sense for what the slightly increased height above deck needs to be.

If you are new to this log and wondering why I am increasing the main top diameter, I will ask you to consider that my addition of 5/8” to the breadth of the hull makes the stock tops seem even more in-adequate than they were to begin with. The other consideration is that I hope to improve the spread of the topmast shrouds; on the stock kit, the slope is negligible.

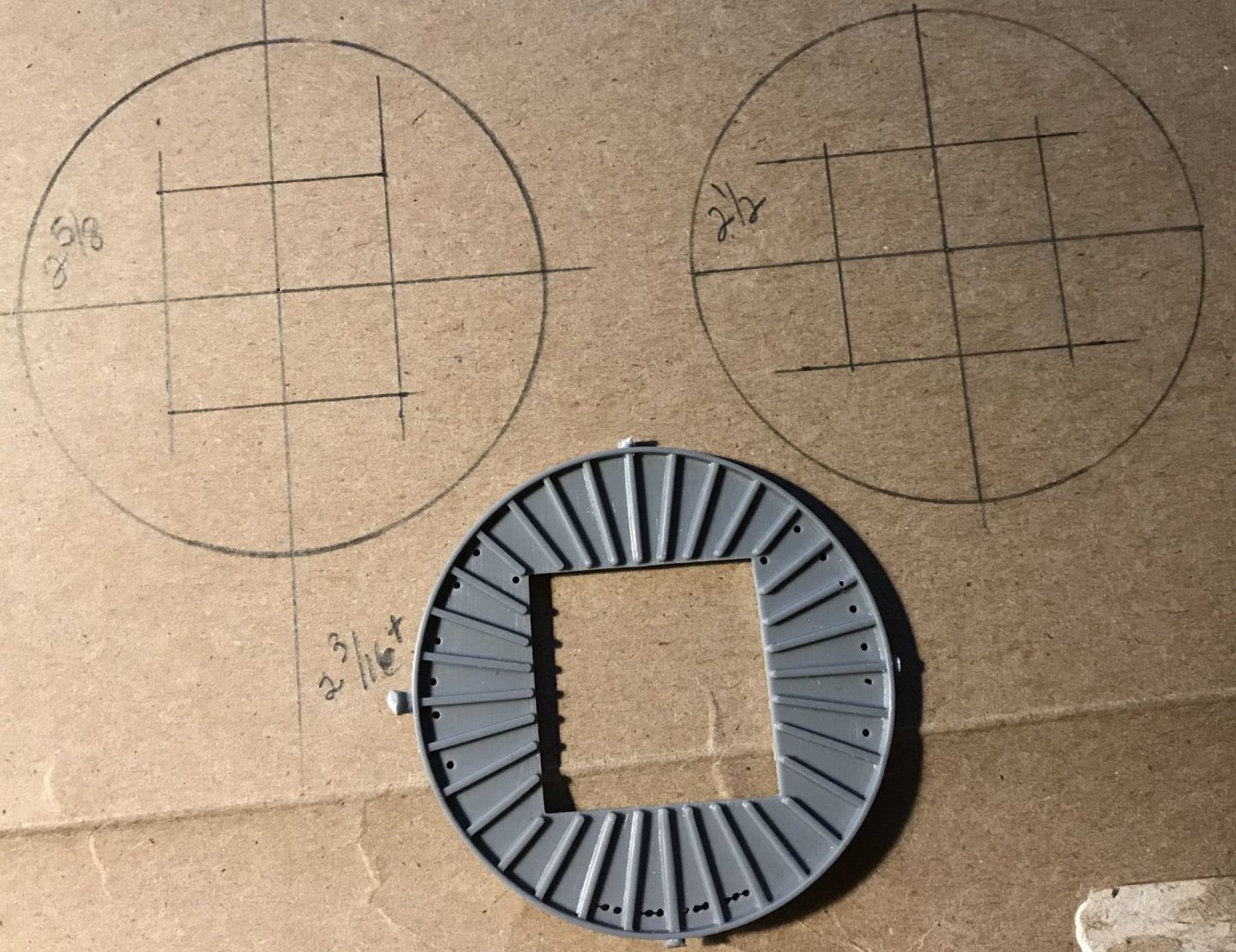

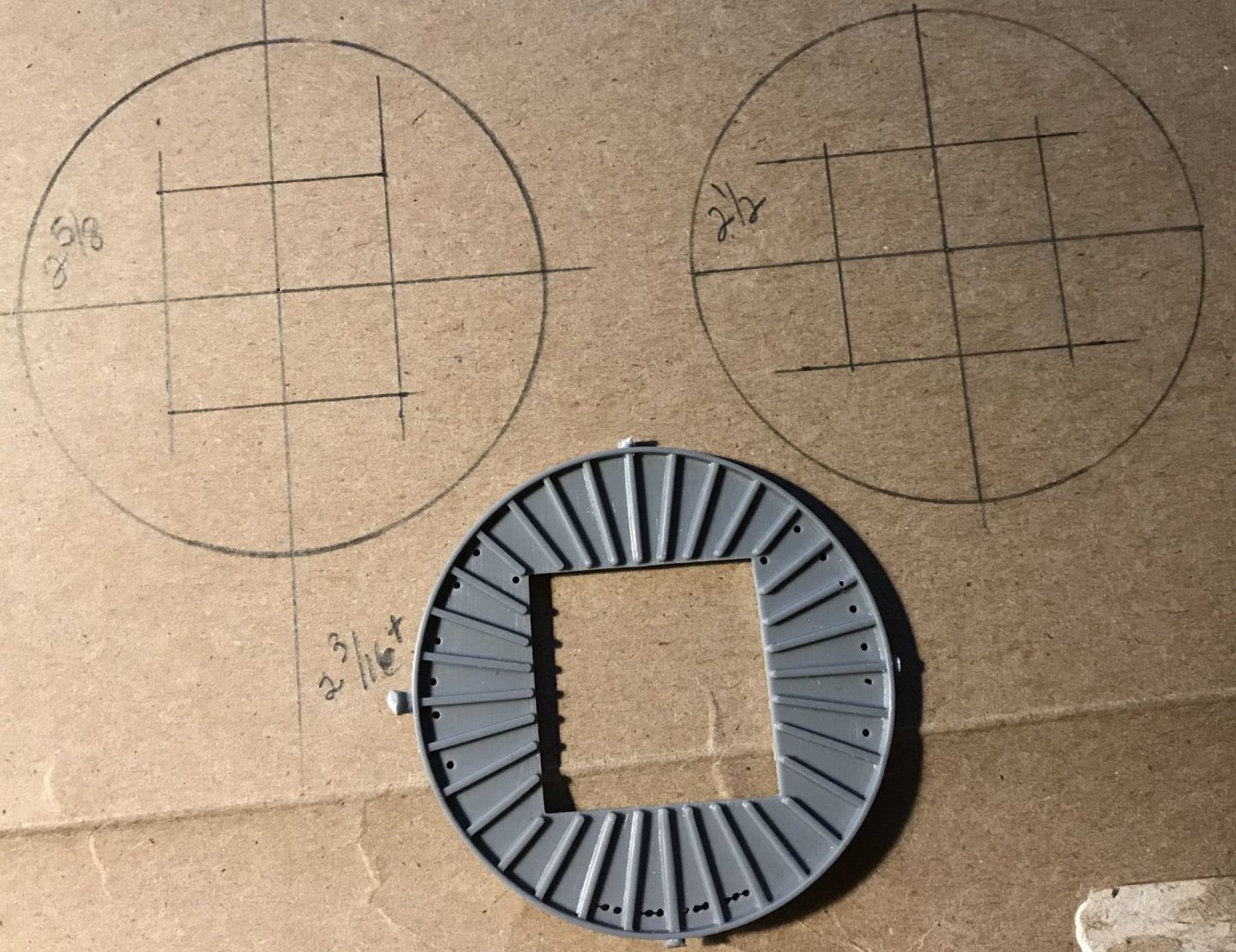

I began by drawing a few different diameters onto a scrap of cardboard:

The stock main top is 2 3/16”. As you see, I went up from there to 2 5/8”. Then, I took each size and placed them on the stock cross trees:

Then, 2 1/2”:

Then, 2 5/8”:

This may seem to be a big jump in diameter, but not so much when you consider the height of the masthead, above the top, and the scale of the cheeks, supporting it.

Now, I know that purists may be appalled that I am not referencing known tables for correct dimensions relative to the height and breadth of the main mast, etc and so forth. On this go-around, though, that is not the kind of rigidly accurate model that I am building.

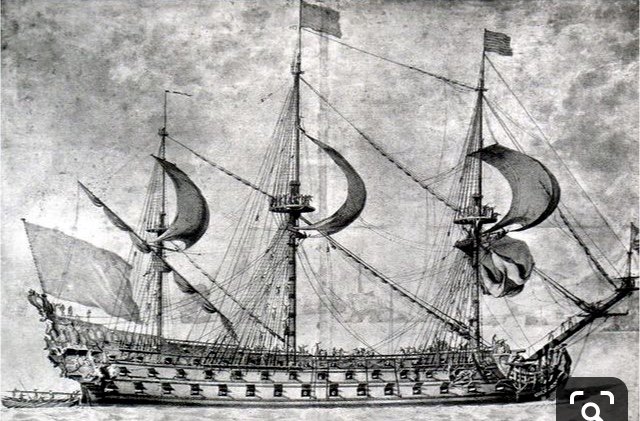

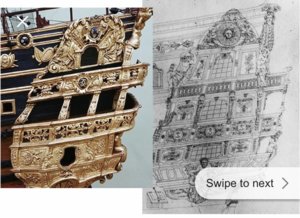

In many ways, this is an artistic and impressionistic model, in which I am trusting my eye and sense for the proportion of these things to arrive at a better overall impression. With specific regard to the tops, what I am going for is what you see in this Puget portrait of what I believe is the Royal Louis of 1692:

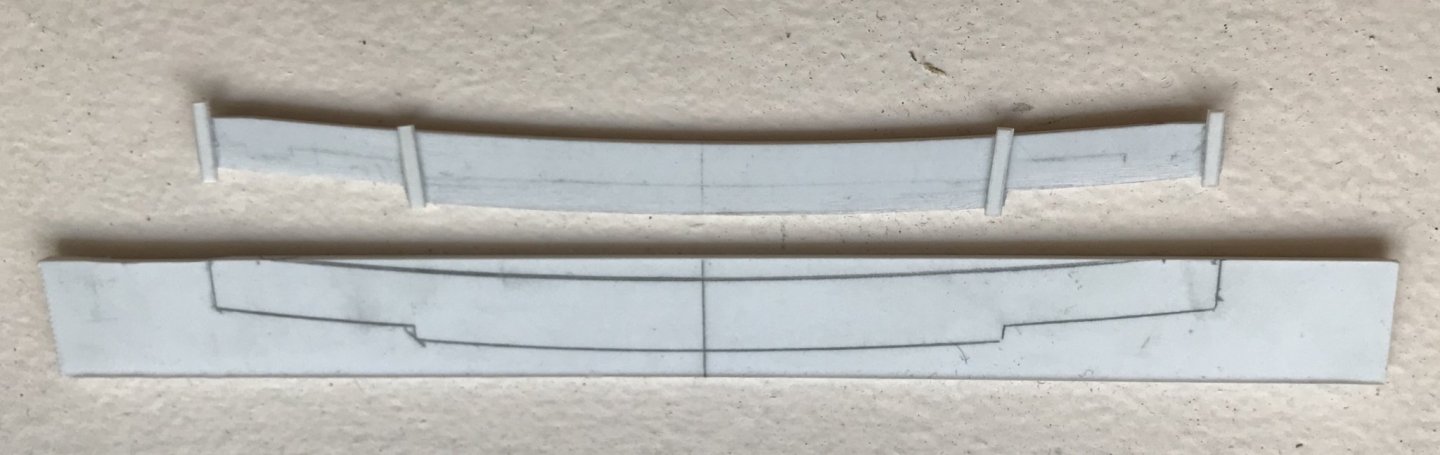

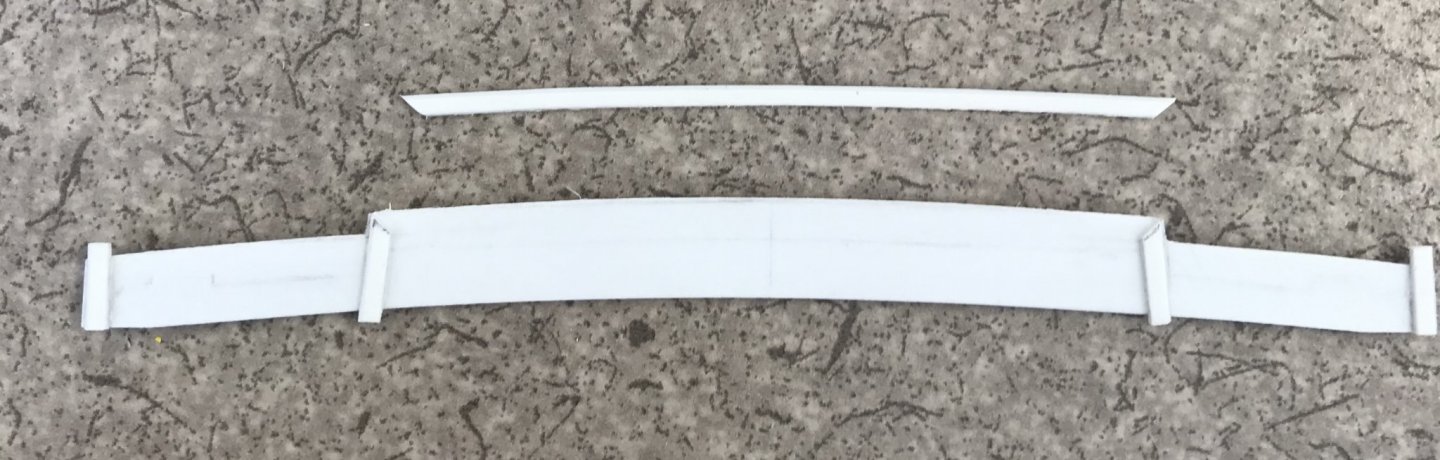

Ultimately, I decided to go ahead and pattern the largest top in styrene. The tops are not difficult to make, but they present an opportunity to incorporate a wealth of detail that is missing from the stock tops.

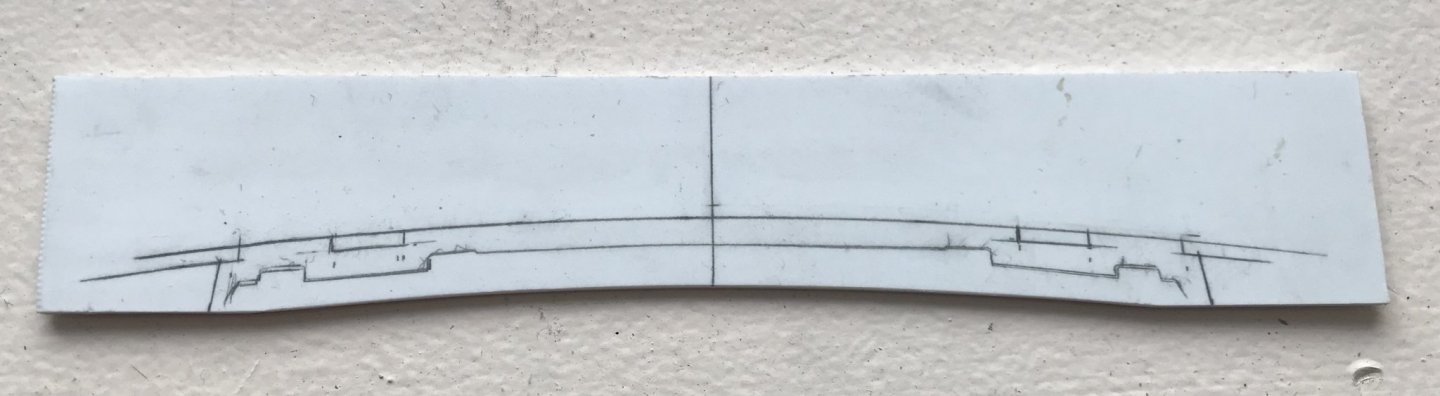

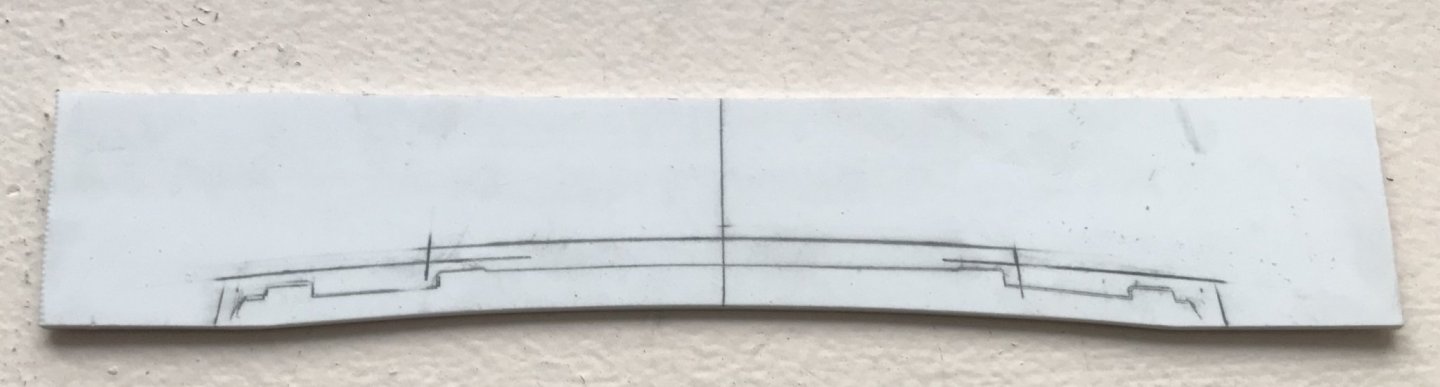

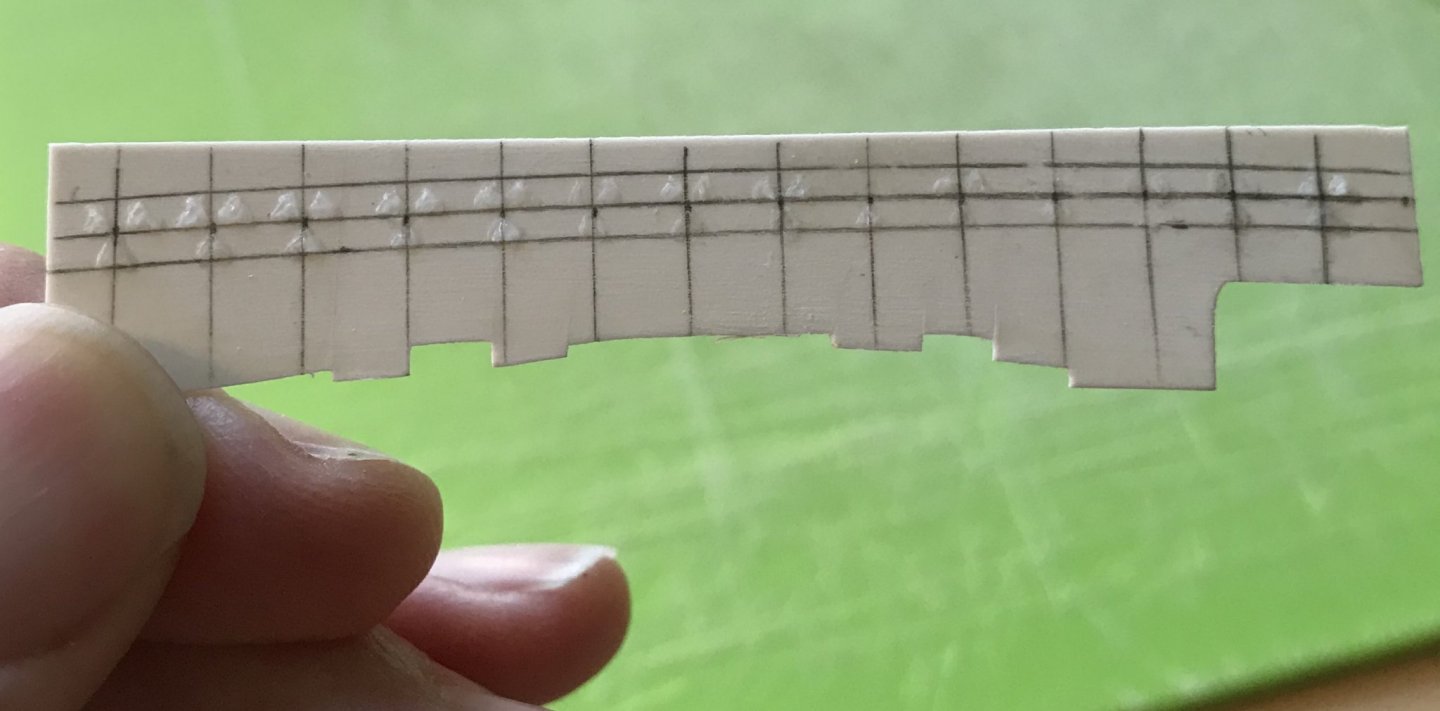

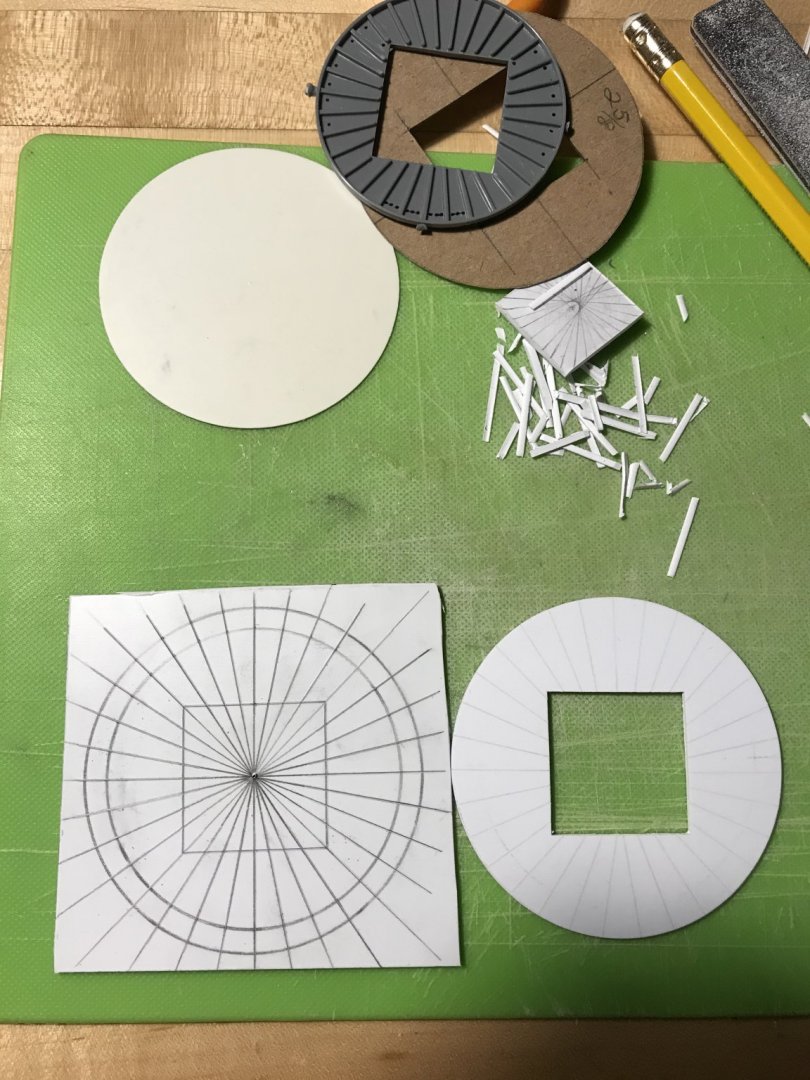

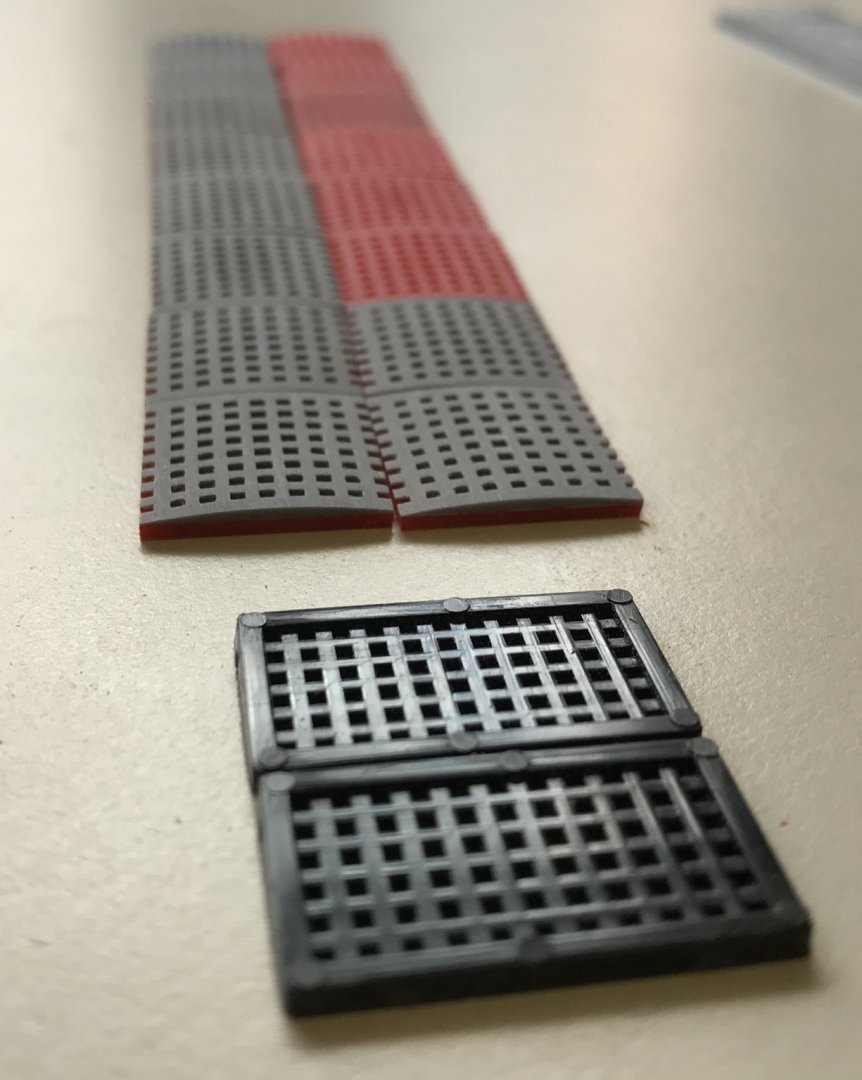

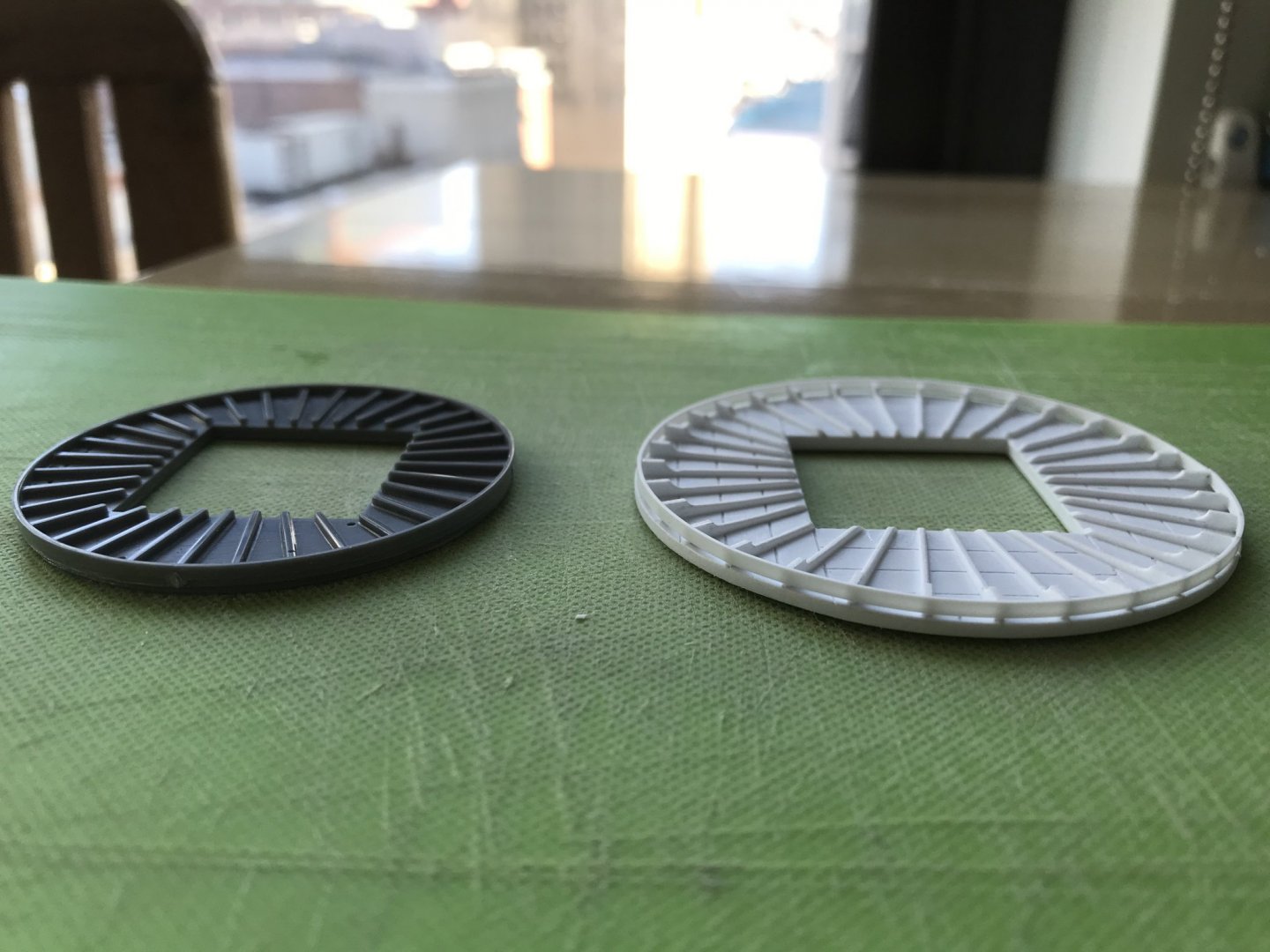

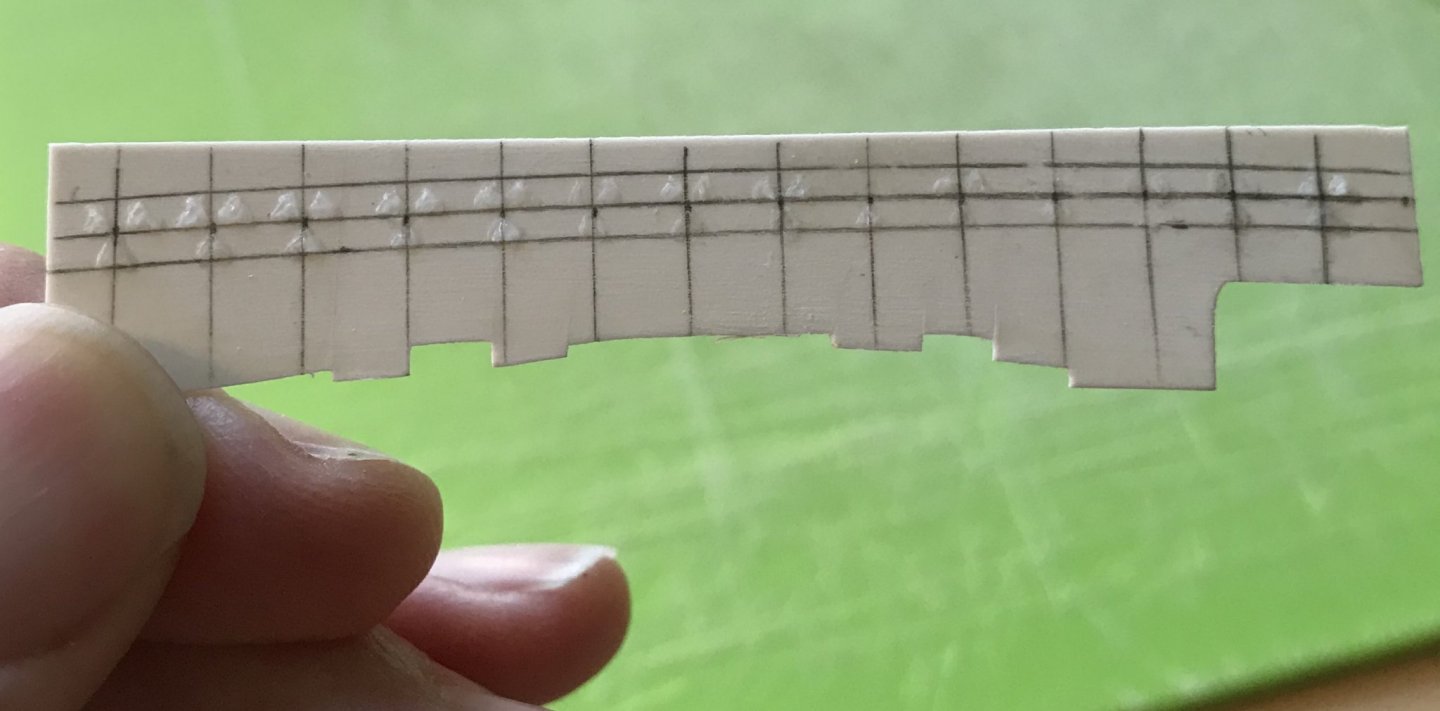

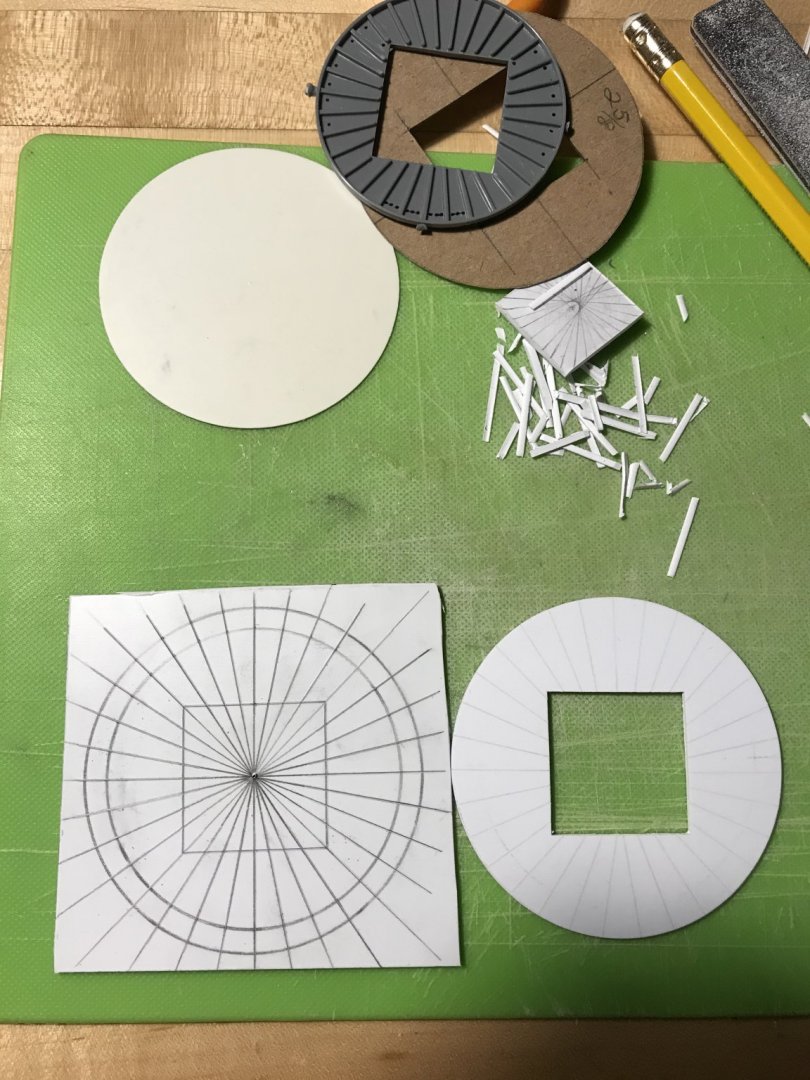

My first attempt at laying out the ribs wasn’t quite right, though:

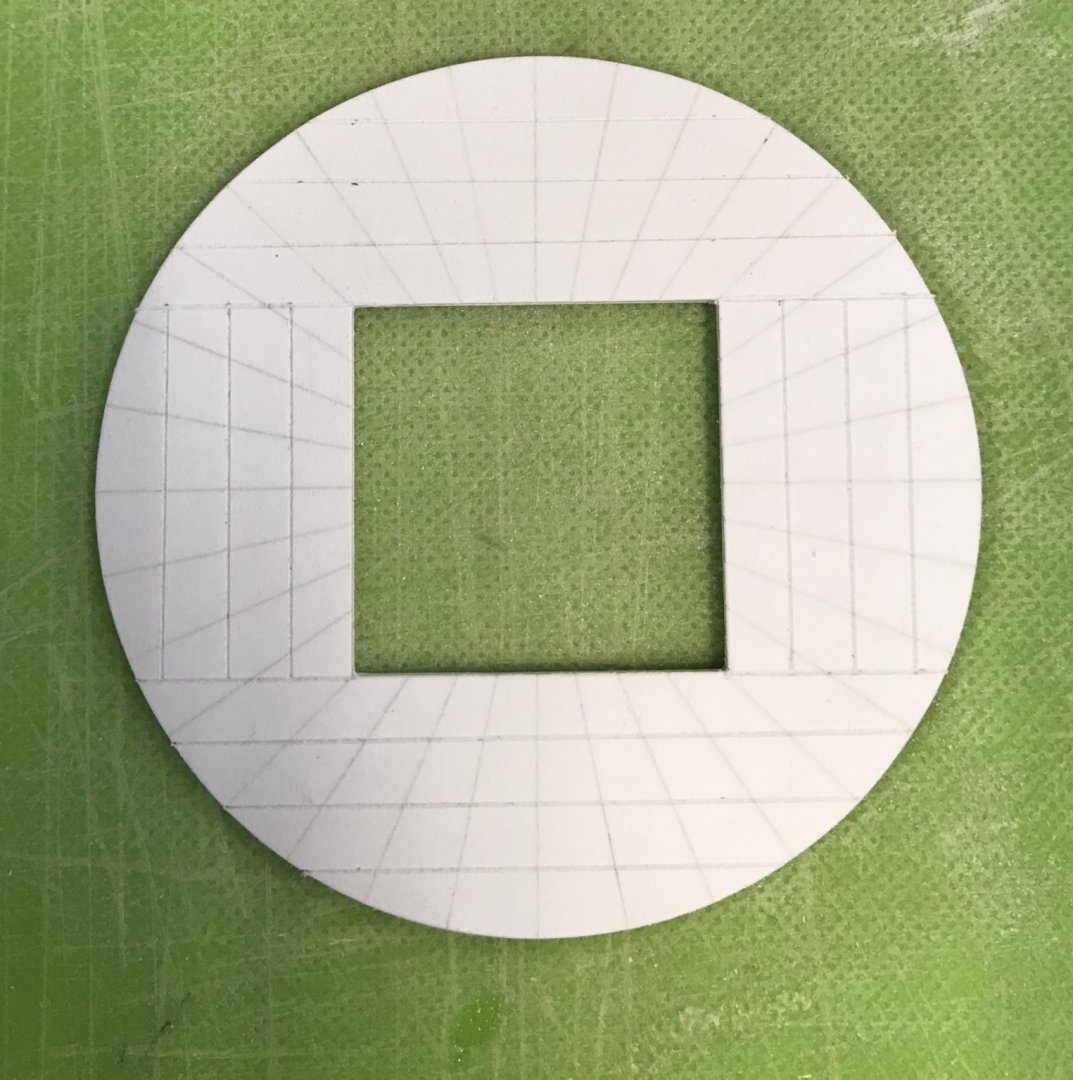

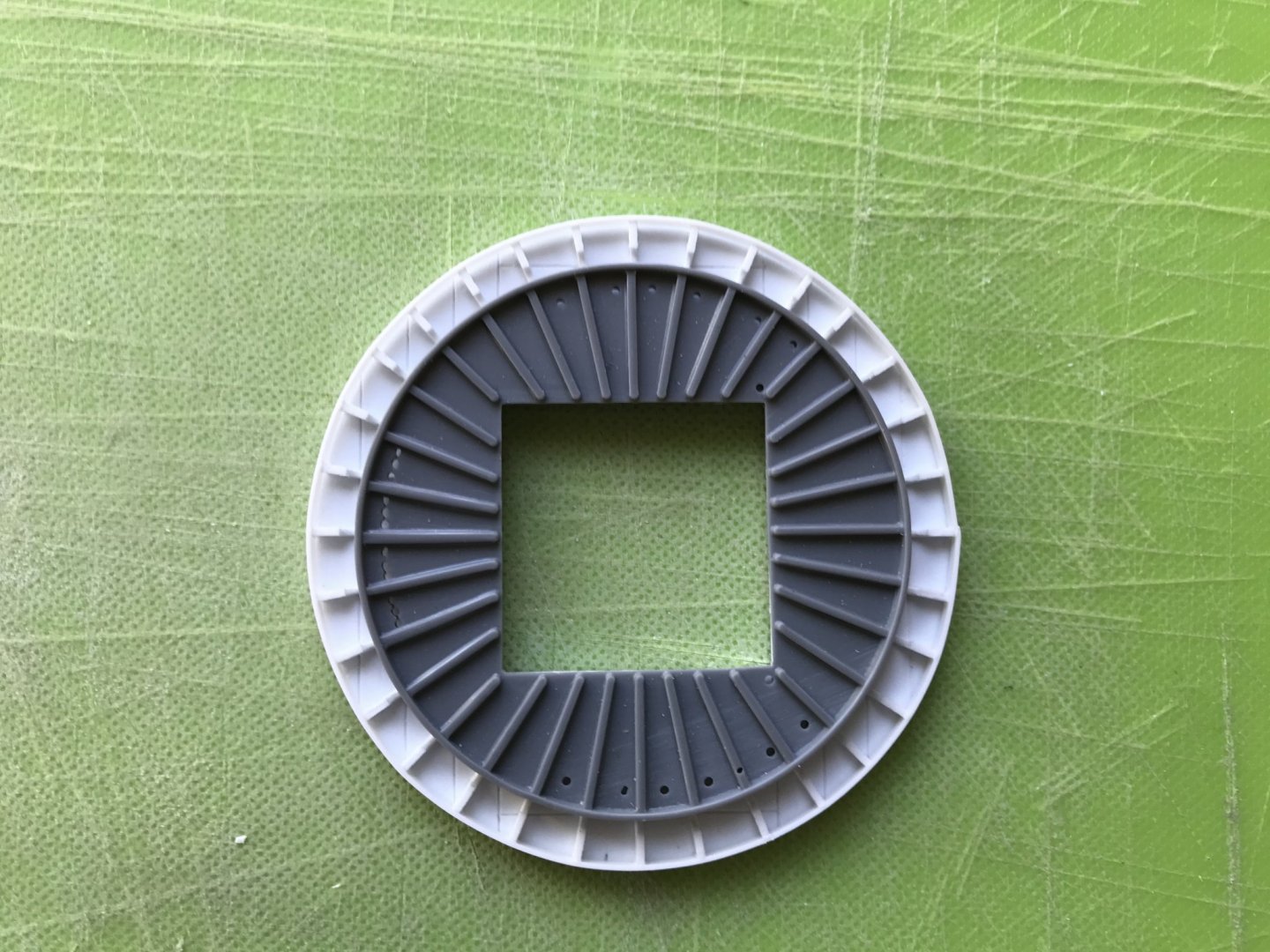

On the right, you can see that the rib layout is slightly off-center; there should be a rib radiating from each corner of the lubber hole. Rather than expend all of that effort to carefully make and glue all of those ribs to a wrong layout, I decided to just make a new top (on the left)

Each top will have a lower, base layer of thinner styrene, that is of a slightly smaller diameter than the main layer.

The main layer is of 1/16” styrene. I’ll have to rip strip stock from 1/32” styrene sheet for the ribs, and I would like to use 1/2-round moulding for the banding that runs around the perimeter of the ribs.

I will also, eventually, make a lantern for the main top, but I haven’t figured out how I want to approach that, just yet.

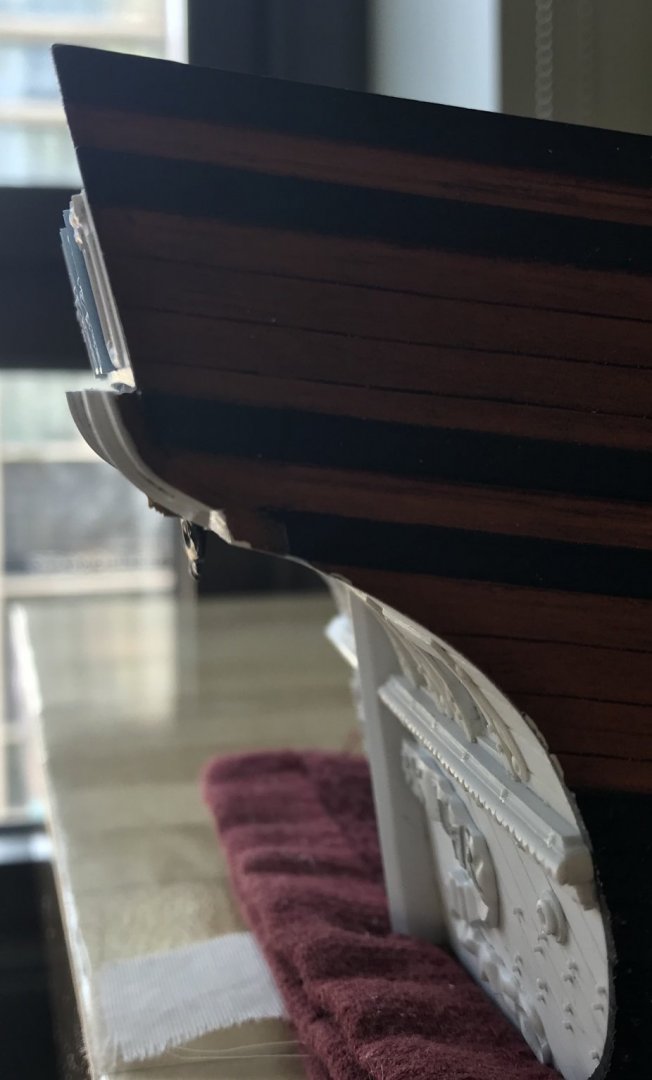

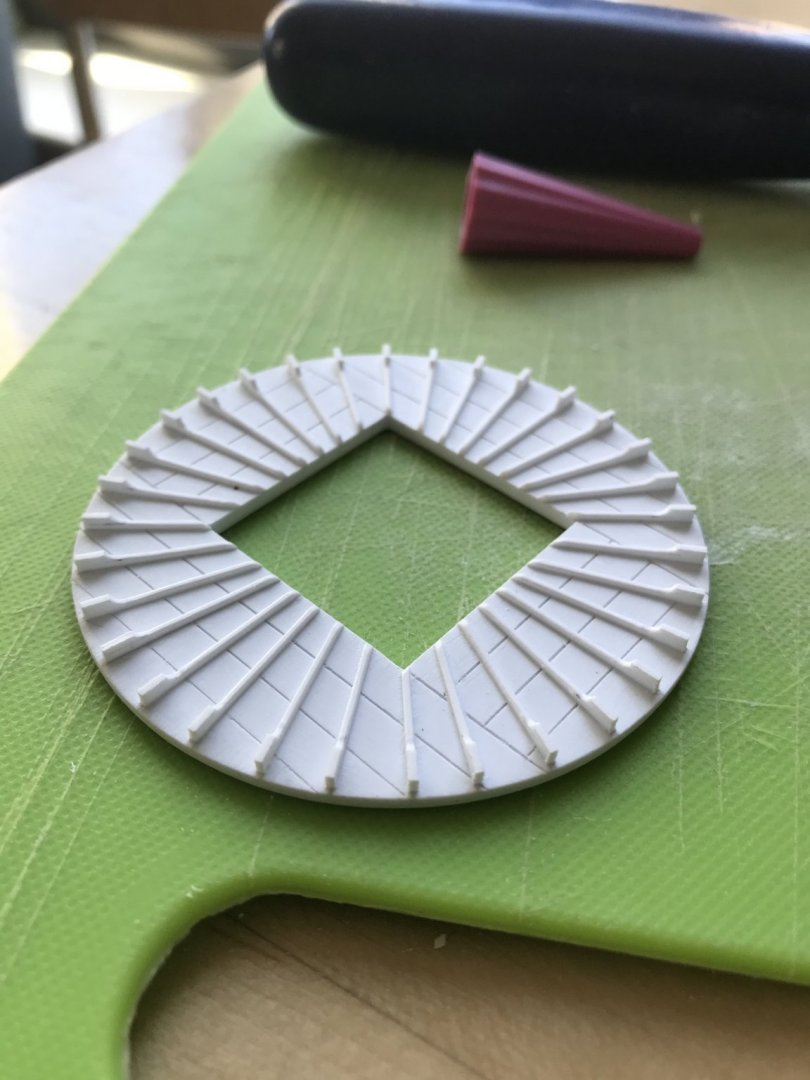

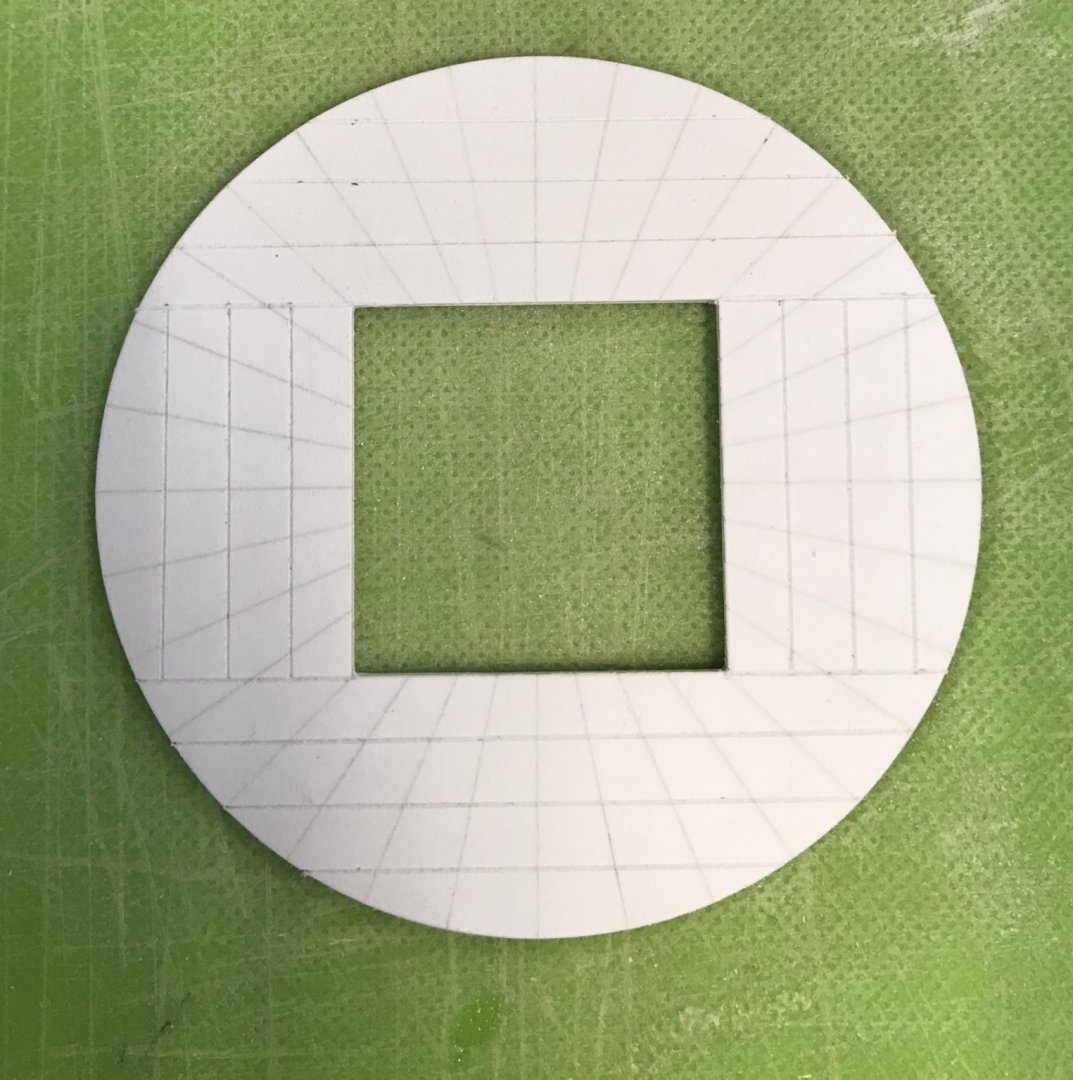

So, here is the top as it stands, now, with the lower and main layers glued together, as well as the rib and planking lines engraved into the plastic:

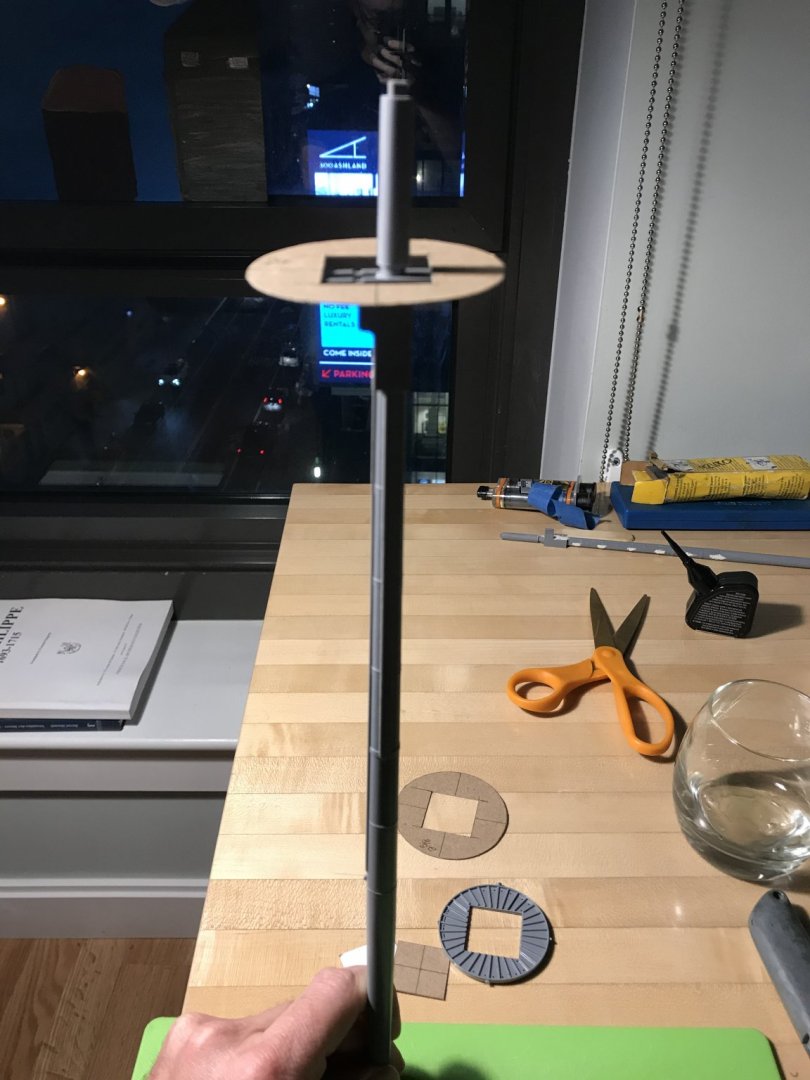

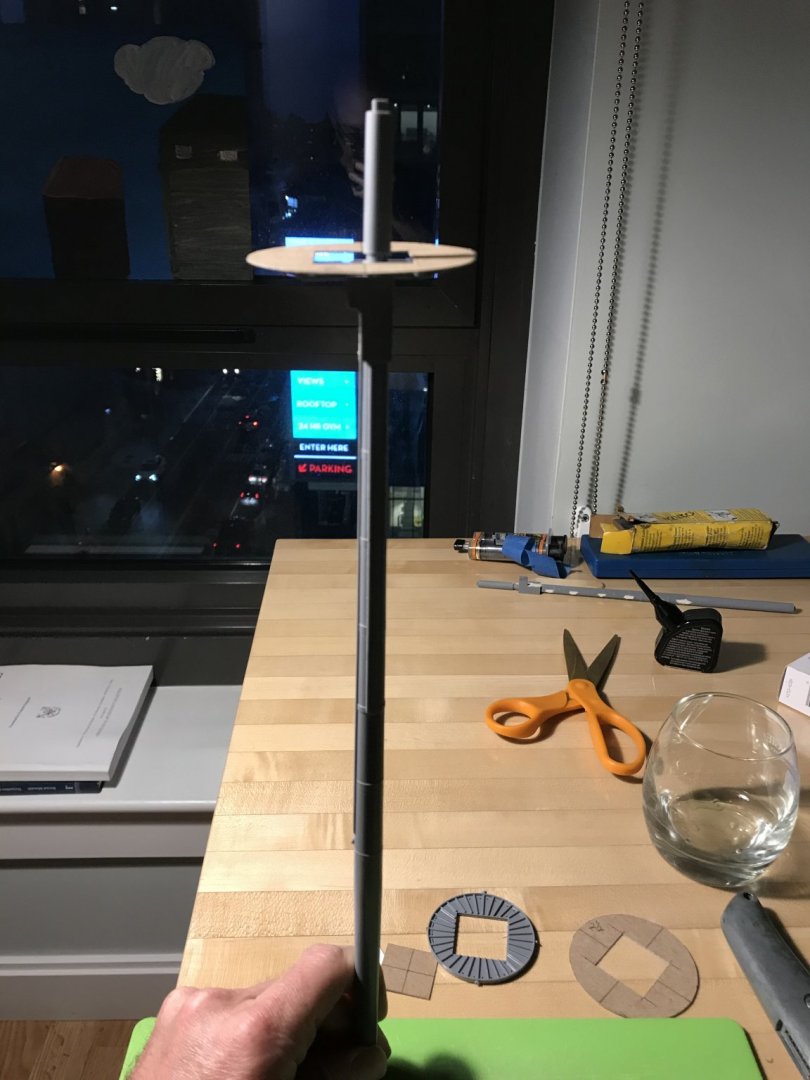

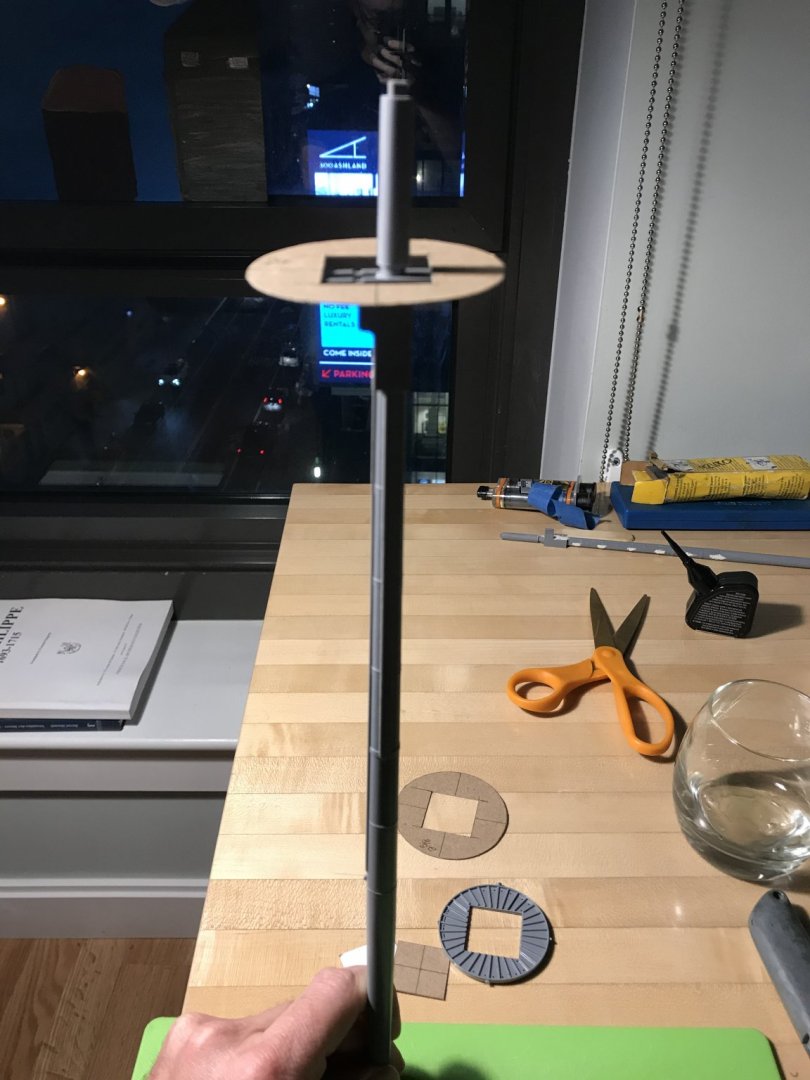

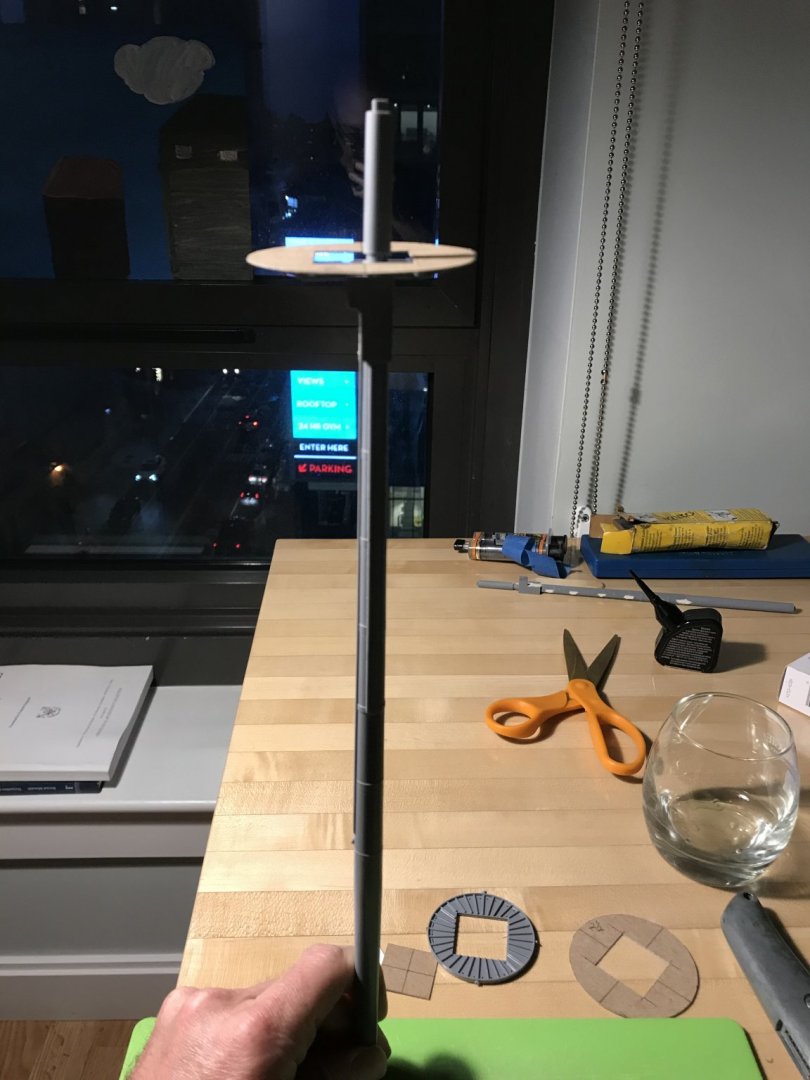

For a sense of scale, here is the top at the main deck level:

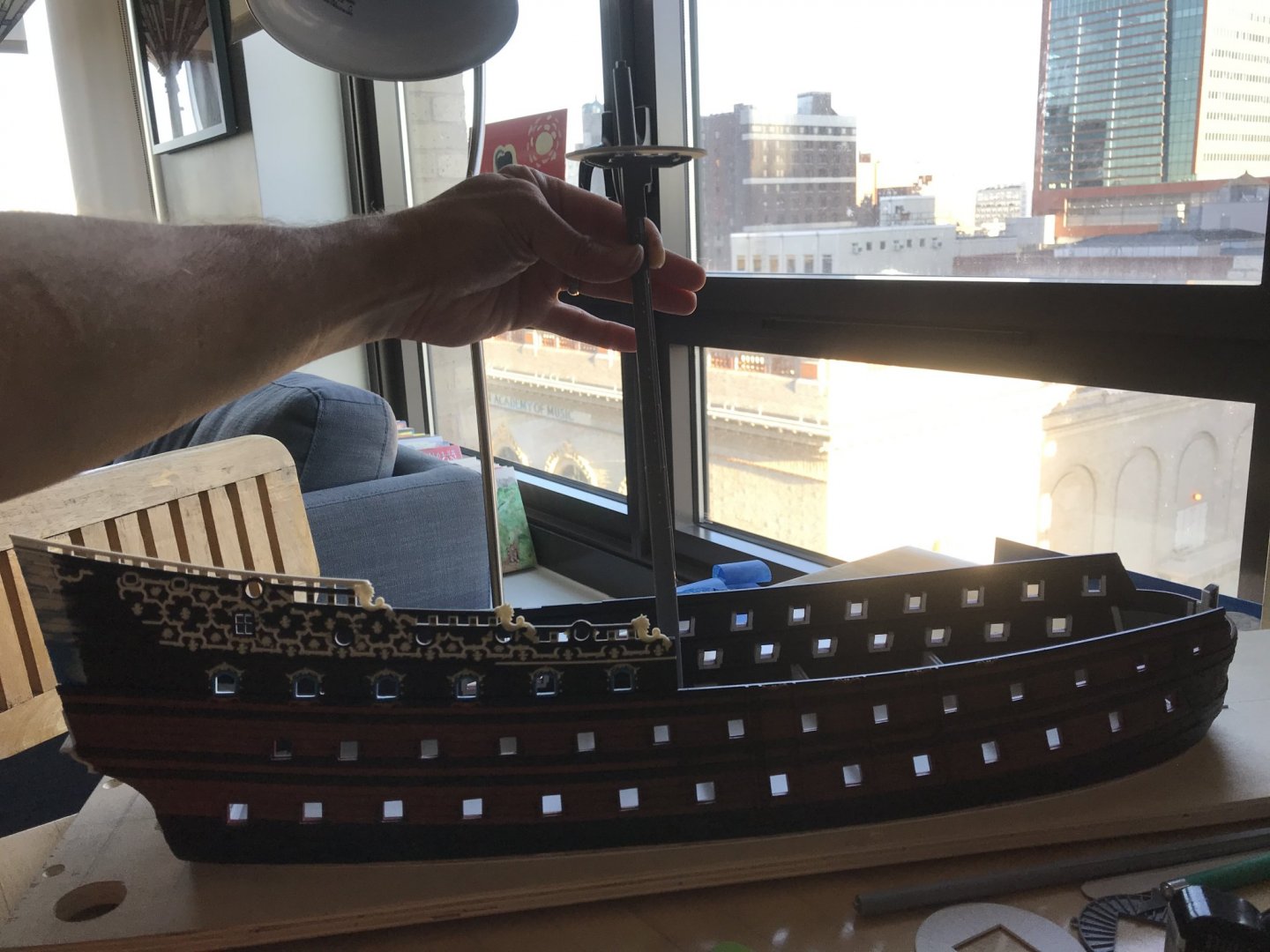

And here is the top on the masthead:

So, next, I was attempting to determine what the new height above the main deck should be.

On the stock main mast, there is a subtle transition where the mast tapers from it’s widest diameter to the narrowing of its foot. That place is where my thumb is in the picture above.

I was considering a 1/4”, 3/8” or 1/2” increase in height above the main deck.

using a straight edge, spanning the main deck ledges (clamps), in the location of the main mast, I determined that there was 2 3/8” to account for from the top of the deck to the plinth base if the model. This dimension includes both the thickness of the deck material, and the camber at the ship’s centerline.

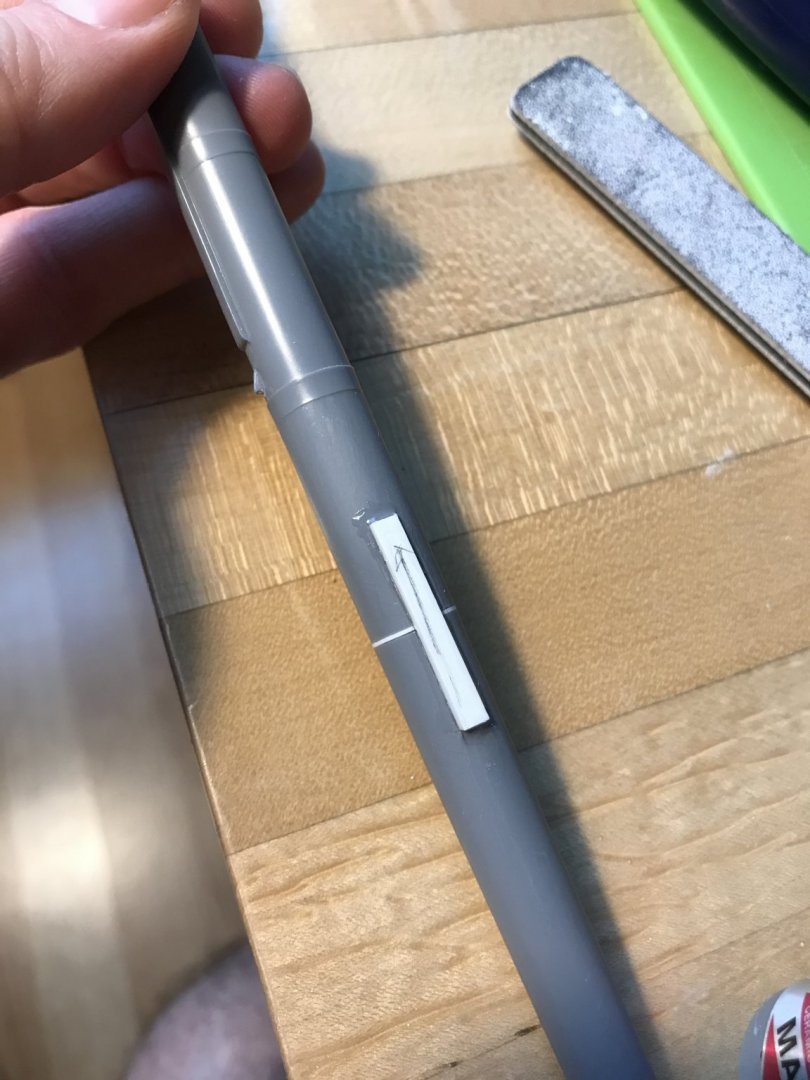

So, to begin with, I measured a 1/2” below where the mast tapers down to its footing, and then I measured down a further 2 3/8” from there. This was to be my first cut-down.

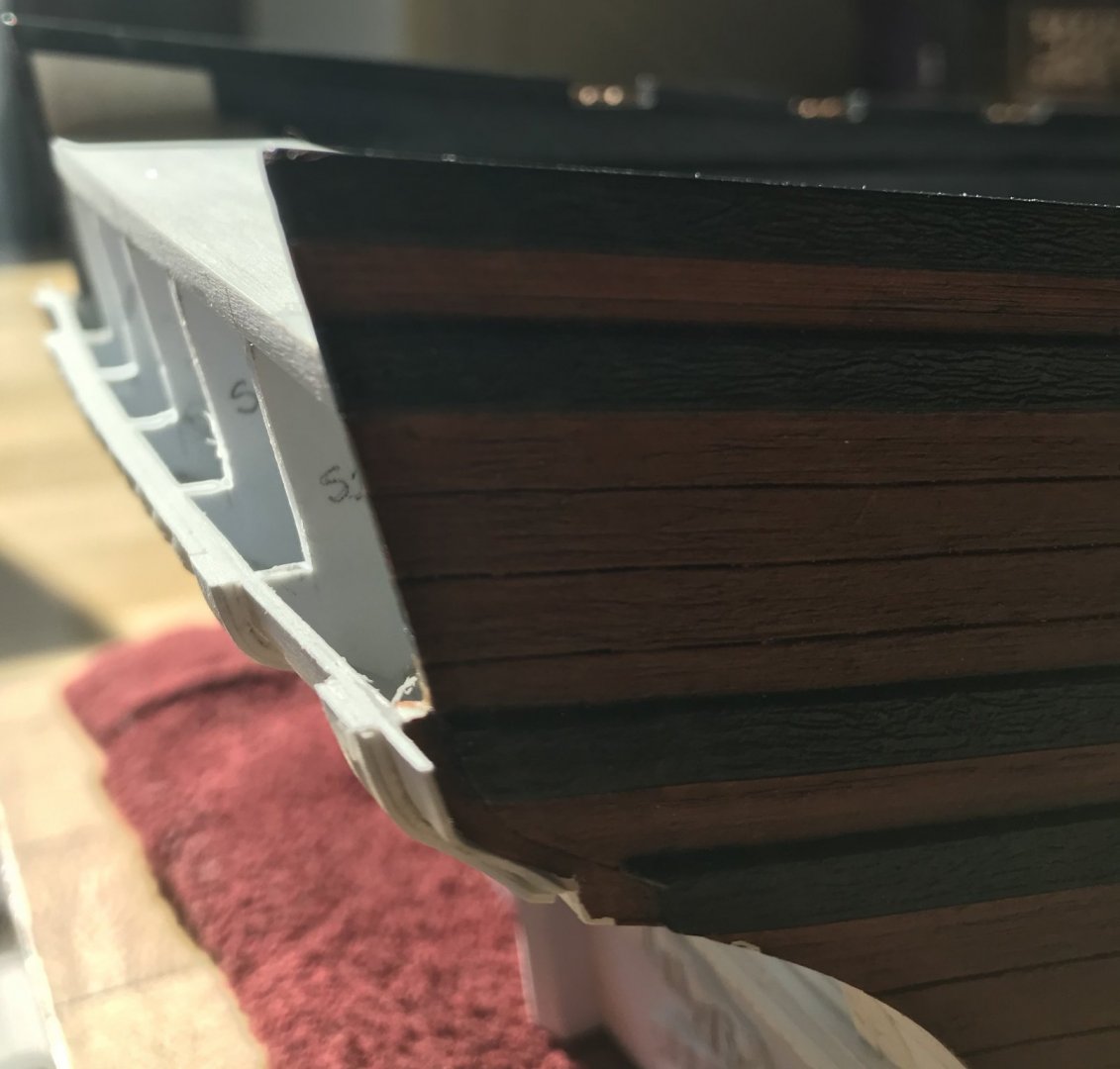

I attempted to account for the rake of the mast top in my cut of the footing. I also placed the starboard upper bulwark, so that I could get a truer sense of proportion:

I liked this. This looked good to my eye. I decided, though, to cut down an additional 1/8”, and I will explain why in a moment. Here’s what 3/8” looks like in better light, after the second cut:

This is what my main mast height will be, and I will use this dimension to establish the relative heights of the fore and mizzen mast tops.

Now, here is why I cut a little further. Bear in mind that I love the comedian Patton Oswalt, and I have recently discovered that Siri will play any stand-up I can think of in an endless loop, almost without repeats; this really helps me keep my mind off of the dreariness of what-all is going on.

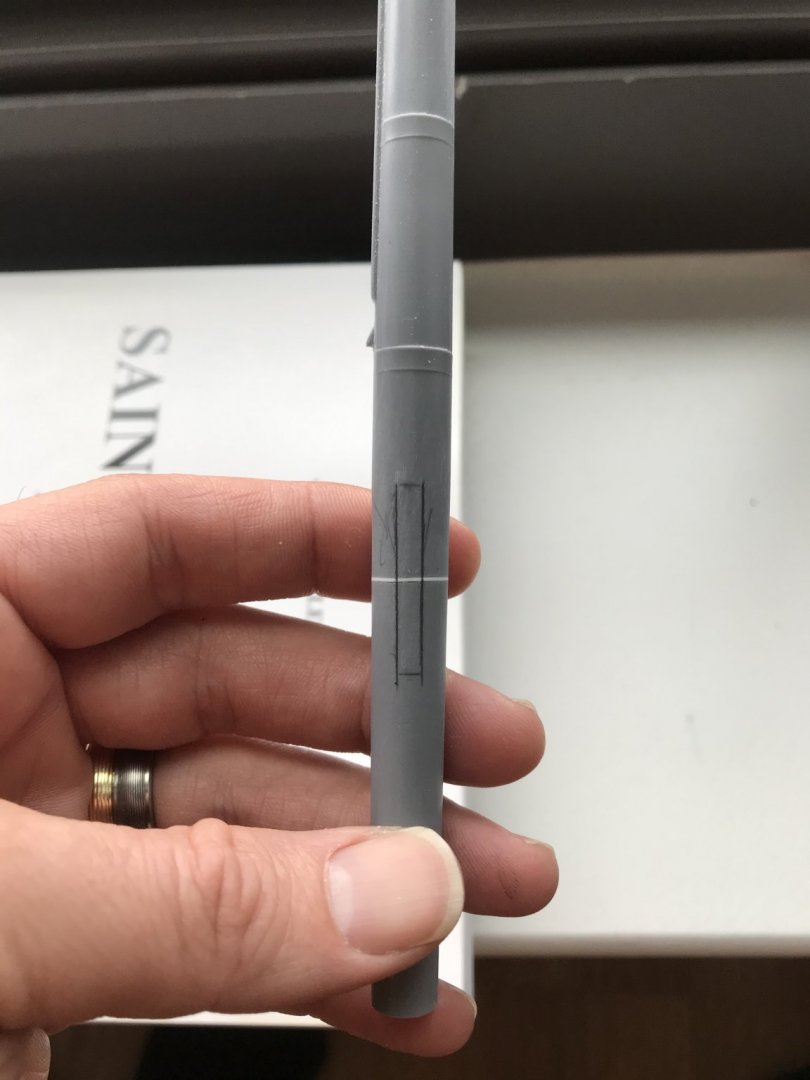

I was listening to Patton and laughing away, as I distractedly taped off my first cut. Unfortunately, I was a little past halfway through the mast when I realized that I had taped off the location where the mast rises above the deck, and not the footing!

Well, that is a BUMMER! I was so angry with myself for falling asleep at the saw, so to speak. I didn’t cut completely through the dowel, on the inside; there is maybe a 1/3 of that diameter still intact.

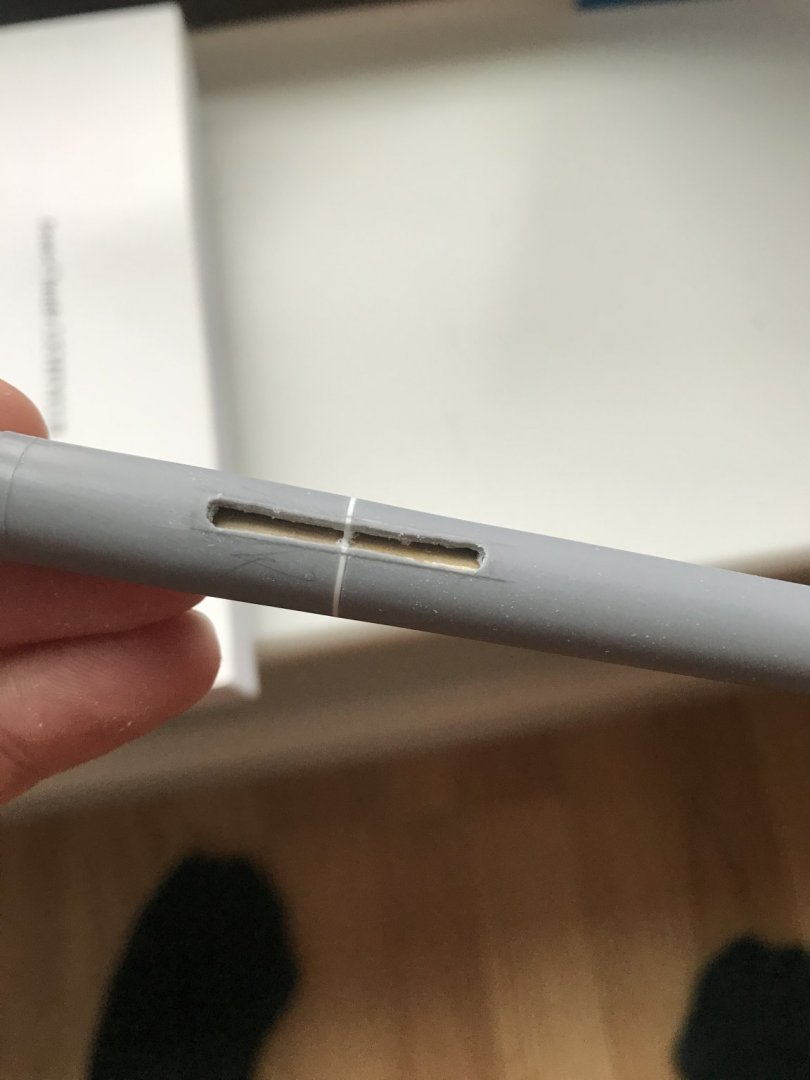

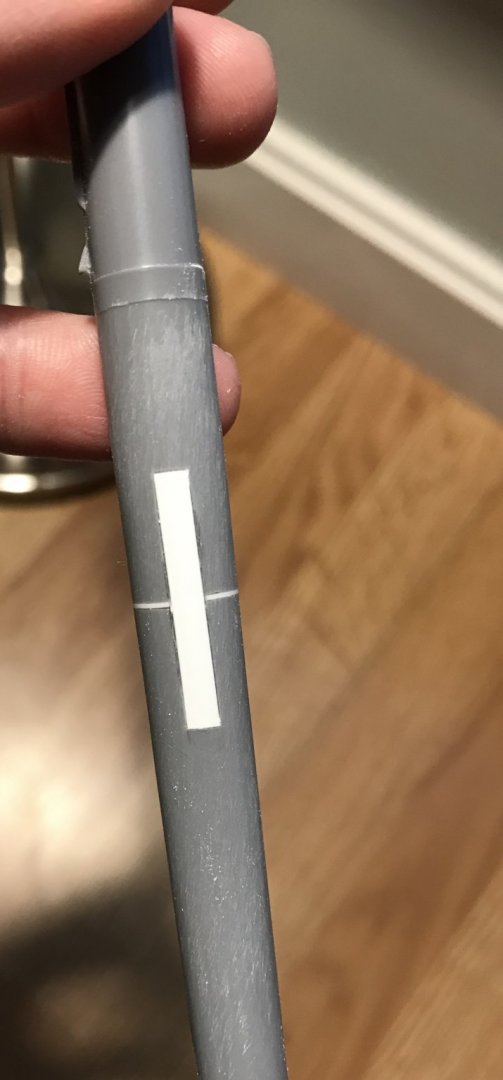

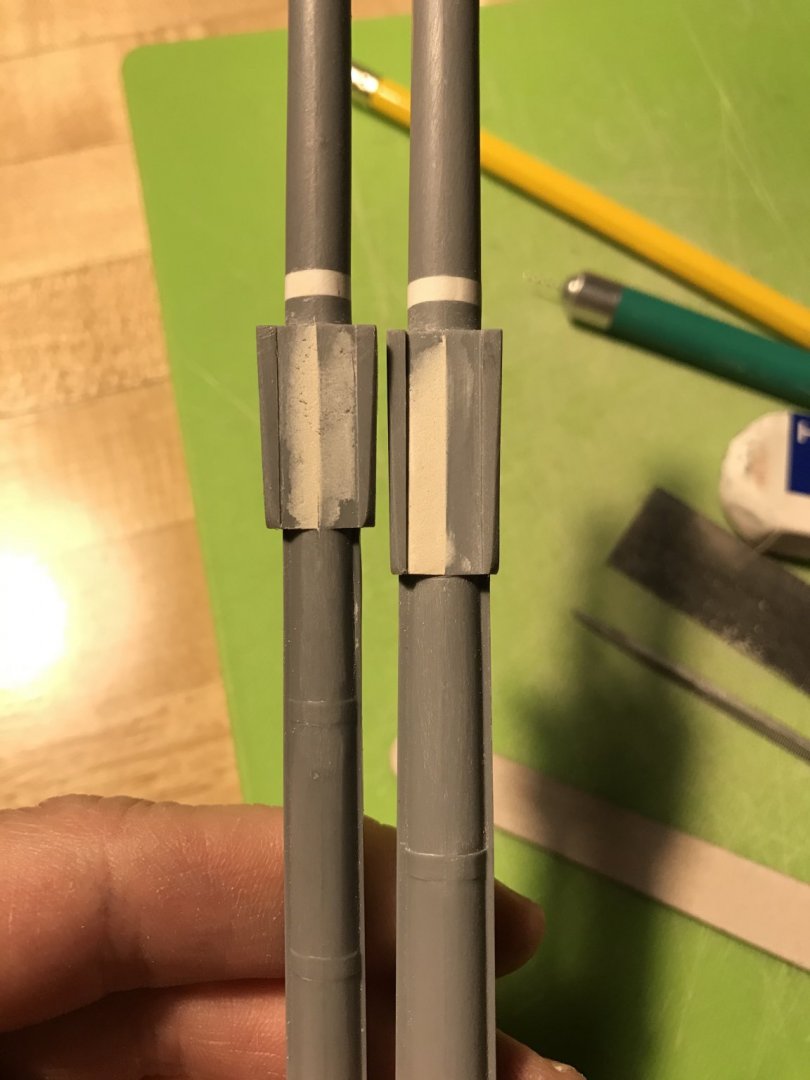

My initial solution was to pack the kerf with medium viscosity cyano and then fill the kerf with perfectly mating styrene sheet. After trimming and fairing the surface, the repair looks well enough. It will be un-detectable, anyway, because it will now sit below the deck surface (the reason for that extra 1/8” cut), and the repair seems strong:

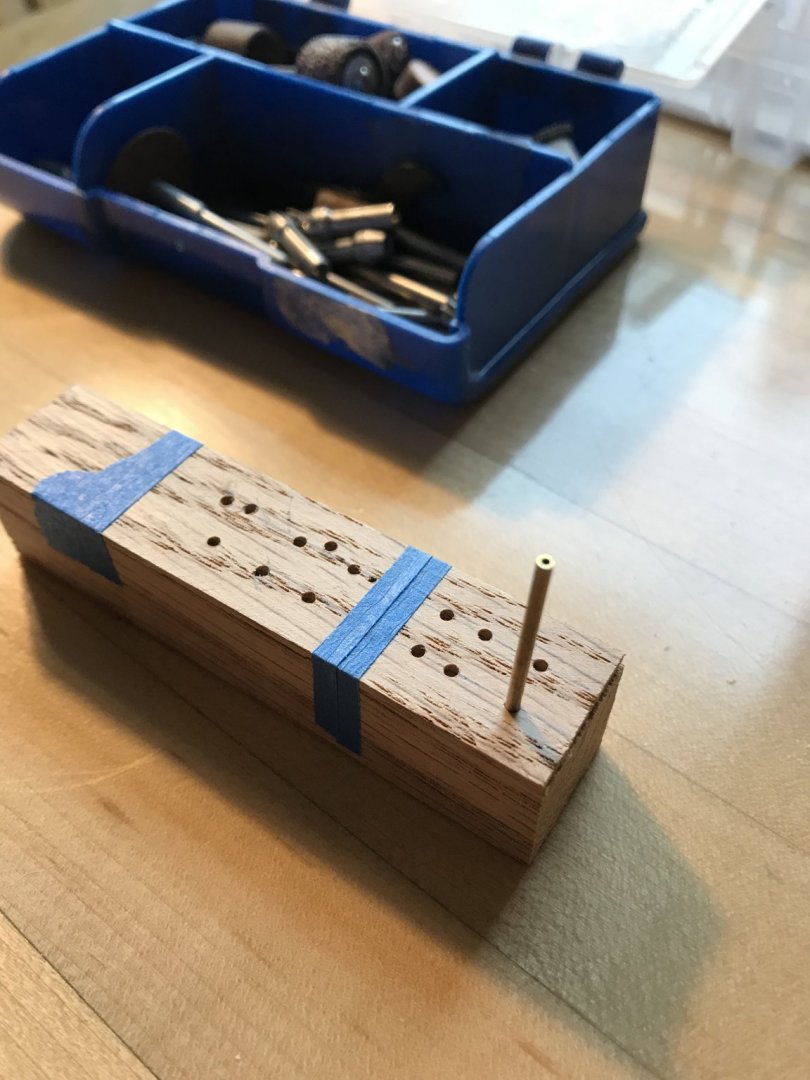

Me being me, though, I wish to ensure that it is extra strong. My first thought was to attempt to drill up through the end of the birch dowel, and into the repaired area, so that I could epoxy in a length of either 3/32” or 1/8” brass tubing:

I am skeptical, though, that even if I work through a progression of bits - that I will be able to keep a drill bit on-track through that expanse of end-grain.

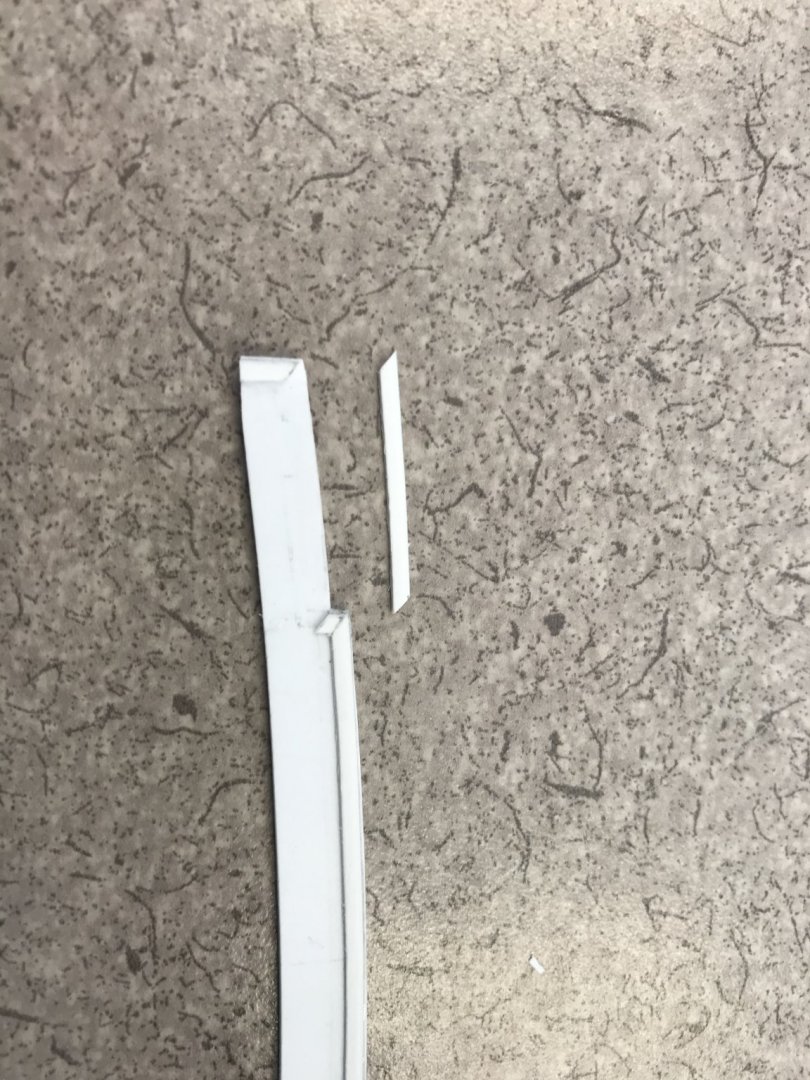

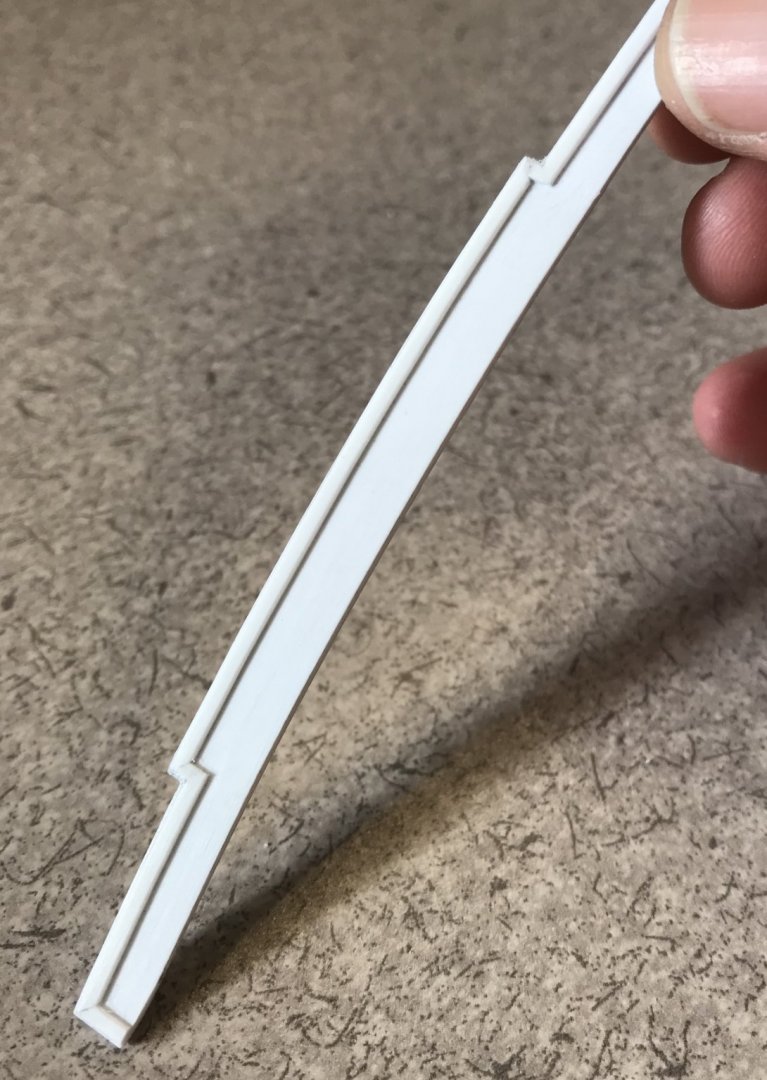

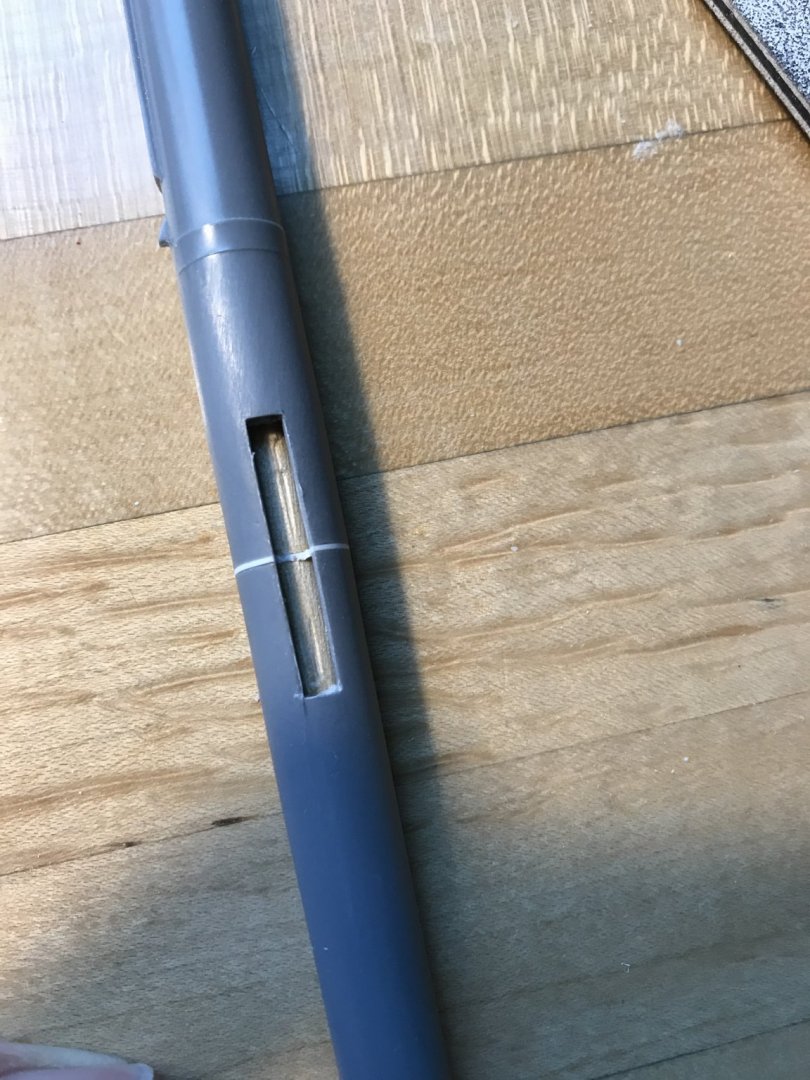

My woodworking background, on the other hand, has given me another, I think, safer idea. Much as you would to stop an end-check in a solid wood table top, for example, I can let-in a key (maybe dovetail, but considering the size, probably not) that crosses the repaired kerf. The goal is to get deep enough in the dowel to increase glueing surface area and unify the whole construction:

This 1/8” styrene extrusion should be up to the task, and it matches my smallest woodworking chisel. A half inch above and below the kerf will be more than enough, and my repair will never be in danger of failing. If I don’t do a perfect job of inletting, the gel cyano will pick up the slack, and this reinforcement will also be undetectable.

So, a Dremeling we will go! And with much greater care, this time

- I asked the dental tech at my last crown reconstruction whether he had hobbies, and if he had ever considered ship modeling, in particular.

- I asked the dental tech at my last crown reconstruction whether he had hobbies, and if he had ever considered ship modeling, in particular.