.

It can be said that the work of Portuguese shipwright Manoel Fernandes from 1616, Livro de Traças de Carpintaria, a particularly attractive collection of designs for various vessels, from the largest merchant nao, through sailing warships and rowing galleys, to the smallest boats, accompanied by technical descriptions and fairly detailed dimensional specifications for specific types of vessels, is not widely known to the general public, and even those actively involved in this field refer to this work extremely rarely and in a rather cursory manner, particularly without delving deeper into strictly technical issues. My investigation of one of the cases contained therein, too, had to be paused for a few years due to the exceptional linguistic hermeticism of Fernandes' text. It was only with the help of a native speaker, @Arthur Goulart, who recently translated the long-transcribed text, that I was finally able to unblock this project.The choice of this particular project for analysis, among all the others in this collection, was admittedly quite random, but from the point of view of recognising the design method employed by Fernandes, this is of little importance, since in this conceptual sense it is universal, i.e. identical for all other Fernandes' projects. For other types of ships described by Fernandes, of different proportions, only the specific values entered into this universal parametric model change.

This is about a design method in the general Mediterranean tradition, which was also adopted in England in the second half of the 16th century, and as a result, the fundamental features of this Mediterranean method are also described in the earliest English shipbuilding manuals up to the second quarter of the 17th century, and can also be identified in plans of English origin from that period.

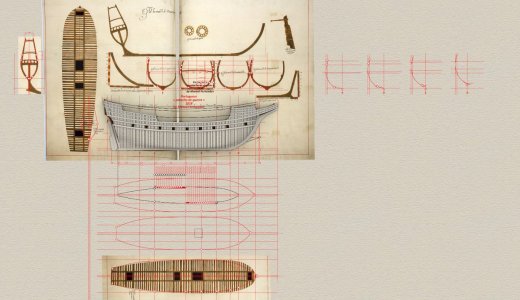

Among these fundamental features, which testify to the above conceptual similarity, the following should be noted: geometric construction of the master frame normally consisting of three sweeps of constant radius (sometimes more or even less — just two, which is not particularly significant for the essence of this method); forming the hull shape by a single set of master frame template, transformed (transversally moved and rotated) over the ‘entire’ length of the hull, or at least between the quarter frames, and guided by the specific set of rising and narrowing lines — the line of the floor and the so-called ‘bocca’ line, the latter coinciding with or parallel to the deck line; and finally — geometric elements of the hull bottom (so-called hollowing/bottom curves), connecting the hull body proper with the keel assembly, defined at the end of the design process.

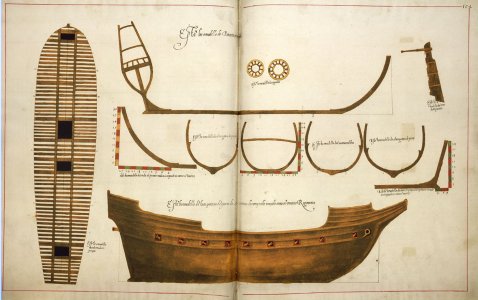

Fernandes' drawings, although visually impressive on the one hand, are not the epitome of precision and are primarily illustrative in nature, apparently to facilitate and encourage a favourable assessment by a decision-making body. However, they did not need to be dimensionally accurate, since this particular design method, due to its relative procedural simplicity, did not actually require the prior preparation of reduced-scale plans on paper, and the actual construction could be started immediately on a real scale, while the written dimensional specifications prepared in advance could be completely sufficient to commence the work.

Examining this case was by no means an easy task of just following a given recipe, as Fernandes basically limited himself to providing the dimensions of various components of the structure. Ultimately, however, this specific investigation allowed for the discovery of further, previously unknown details or design subtleties proper for this design method.

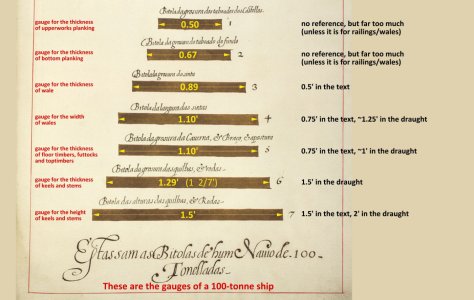

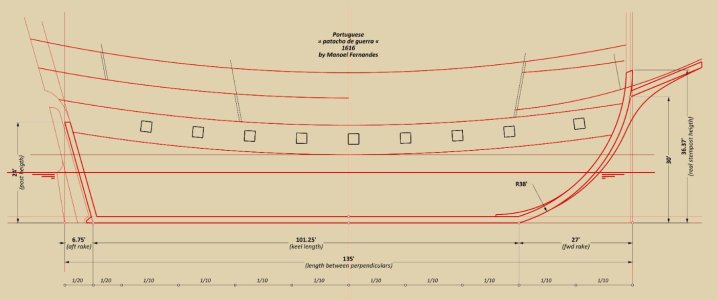

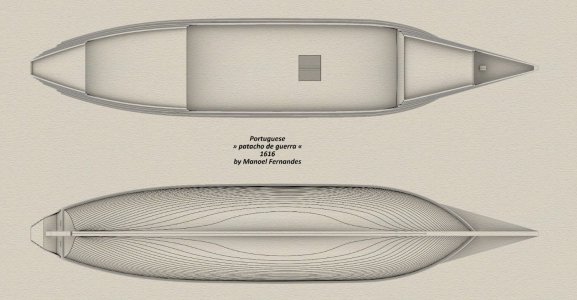

The ship in question was intended to be armed with 18 guns and its basic dimensions are as follows:

Length (between posts): 135 palmos (4.5 x breadth)

Keel length: 102 palmos (3/4 x length between posts)

Breadth: 30 palmos

Depth (distance from the upper edge of the keel to the greatest breadth): 15 palmos (1/2 x breadth)

Waldemar Gurgul

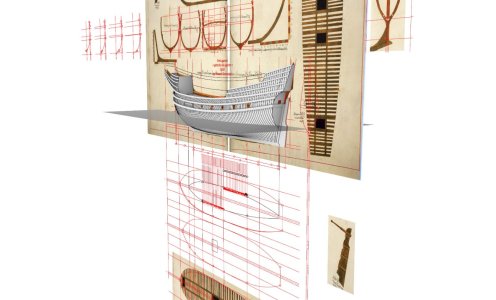

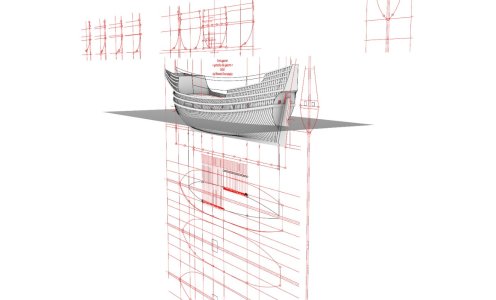

Drawing of the design in question on page 104 from the Livro de Traças de Carpintaria:

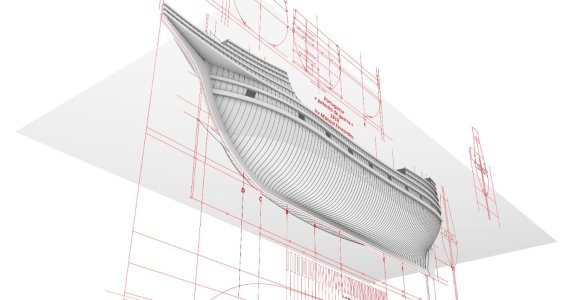

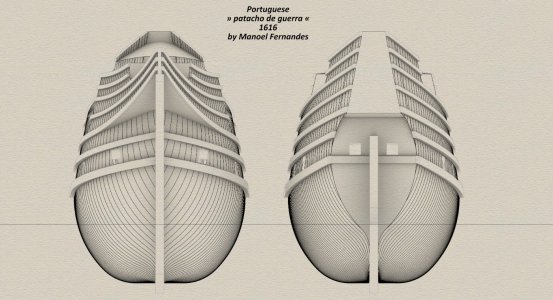

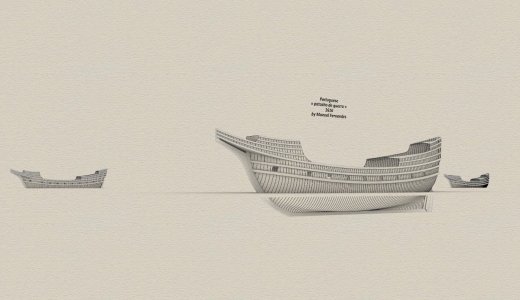

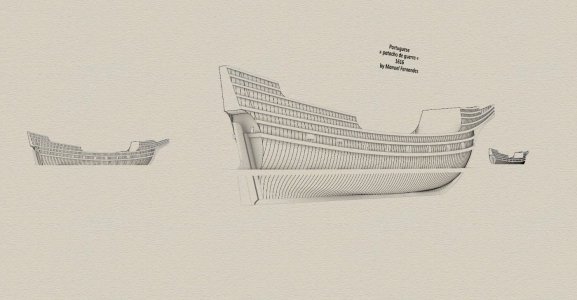

Reconstruction graphics:

.

Last edited:

I use SoS way less frequently, evidently. I have about a thousand questions, but, I think the big one would be: how is the master frame moved and rotated along the boca and rise of the floor lines? The patacho 3D model looks incredible btw, I'd love to see that further developed, and well, maybe a set of plans!

I use SoS way less frequently, evidently. I have about a thousand questions, but, I think the big one would be: how is the master frame moved and rotated along the boca and rise of the floor lines? The patacho 3D model looks incredible btw, I'd love to see that further developed, and well, maybe a set of plans!