Greetings all! My previous post about Oils and their variations would be incomplete without a discussion about other finishes and their techniques. while I am in no way claiming to be an export in wood finishes, I will simply relay what I have researched from the real experts, and what they are saying. They are Christophe Pourny and Bob Flexner. You can get all of the details in their books.

Staining the wood

Staining colors the wood’s surface in order to highlight its natural tone, enhance it with a decorative cast, or give it a different character completely Staining can also serve as a strategic purpose, helping to even the tone between different cuts of the wood used on a piece of furniture or to help patches and repairs blend in. Of all the steps in finishing, staining, causes the most problems. Because of such difficulties as splotching, streaking, color unevenness, and incompatibility between stain and finish, many peoples avoid the use of stains altogether.

You probably think of staining as simply applying a colored liquid to bare wood. Staining is this, but it is also much more. It includes glazing, toning, and shading, all ways of applying a colorant so that you can still see the wood through the color. In all cases, the key to staining is translucency; the goal is not to obscure the wood like paint, but to add a wash of color that lets the grain show through. Most likely, you choose a stain for its color. You're probably not thinking about other important considerations, such as what the stain is made of, how fast it dries, or how it will behave on the wood.

Some stains, such as Watco and Minwax, penetrate deep into the wood; others, such as Woodcote and Bartley, very little. Some stains, such as Behlen 15 Minute, dry fast; others, such as Red Devil, slowly. Some stains, such as Carver Tripp Safe and Simple, raise the grain of the wood; others, such as Carver Tripp Wood Stain, don't. If you've done much staining, you've surely noticed some of these differences.

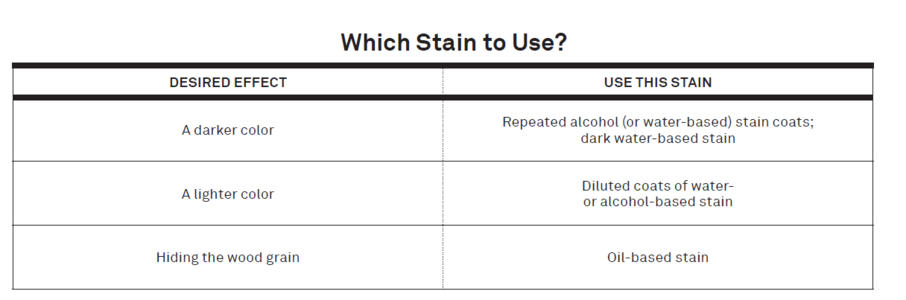

In the following posts, we will get deep dive into each of the available types of stains available on the market. For now please check the table below, it describes each of the stains its properties and use.

To be continued in the next post...

Staining the wood

Staining colors the wood’s surface in order to highlight its natural tone, enhance it with a decorative cast, or give it a different character completely Staining can also serve as a strategic purpose, helping to even the tone between different cuts of the wood used on a piece of furniture or to help patches and repairs blend in. Of all the steps in finishing, staining, causes the most problems. Because of such difficulties as splotching, streaking, color unevenness, and incompatibility between stain and finish, many peoples avoid the use of stains altogether.

You probably think of staining as simply applying a colored liquid to bare wood. Staining is this, but it is also much more. It includes glazing, toning, and shading, all ways of applying a colorant so that you can still see the wood through the color. In all cases, the key to staining is translucency; the goal is not to obscure the wood like paint, but to add a wash of color that lets the grain show through. Most likely, you choose a stain for its color. You're probably not thinking about other important considerations, such as what the stain is made of, how fast it dries, or how it will behave on the wood.

Some stains, such as Watco and Minwax, penetrate deep into the wood; others, such as Woodcote and Bartley, very little. Some stains, such as Behlen 15 Minute, dry fast; others, such as Red Devil, slowly. Some stains, such as Carver Tripp Safe and Simple, raise the grain of the wood; others, such as Carver Tripp Wood Stain, don't. If you've done much staining, you've surely noticed some of these differences.

In the following posts, we will get deep dive into each of the available types of stains available on the market. For now please check the table below, it describes each of the stains its properties and use.

To be continued in the next post...