How FUN is this exchange! Congratulations, Waldemar, for a significant contribution, and to you, Fred, for the discussion and engagement! Just great stuff!

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Vasa 1628 – engineering a ship

- Thread starter -Waldemar-

- Start date

- Watchers 25

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2020

- Messages

- 80

- Points

- 103

Vasa is the length it was intended to be, within a meter or so. It is also the height it was intended to be from the earliest design discussions, the major change from specification is in breadth.

Does the height in this context includes the depth of the hull underwater? Was there an initial limitation for the drаught that could not have been exceeded?

.

Thank you very much, Fred, for all the detailed information about the hull shape. As it is not possible to verify all possible variants in one "deal", so I will most likely nevertheless check the verlanger option first, but not in the classic scenario, i.e. the reworking of an already completely built hull, but rather of the variety of a dramatic change of the design concept already after the start of construction at some stage, with the building material already prepared for the original variant, as you write about it. The inappropriate, too-low run of the line of greatest breadth symmetrically on both sides, the extended stem post, the extended stern post and perhaps something else, is already a number of indications that can hardly be easily ignored (for greater clarity: it's for the assumption that Vasa is a reworked still during construction of a smaller ship of the whole, complete contract, if I remember the circumstances correctly).However, I am away from home for a few more days and do not have access to all the material I should be consulting while making this attempt. I apologise for this delay.

Was there an initial limitation for the drаught that could not have been exceeded?

It may even be possible to write a doctoral dissertation on the subject, but in practical terms it is probably the shortest way to say that a ship of 'similar' size (and sporting tumblehome) should not be submerged more than two-three feet below the line of greatest breadth (admittedly, one of the royal French ordinances of the second half of the 17th century provided for an equalisation of these levels, but it is not entirely clear whether this should be interpreted quite literally, and even less whether the designers complied with this ordinance in such a literal way at all, especially as they must have been aware of its potentially very dangerous consequences).

.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

There was no operational requirement that limited draught, the navigable water in the ship's operational area had plenty of depth to allow a deeper hull. Relatively speaking, Dutch designs of the 17th century have shallower draught than English or French designs of the same displacement, which is related to local conditions in the Low Countries. Dutch designers working in Scandinavia continued to build shallow draught ships, no doubt because these were the hull forms they knew.Does the height in this context includes the depth of the hull underwater? Was there an initial limitation for the drаught that could not have been exceeded?

Fred

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

I would really like to avoid using the term verlanger here, as it has a specific meaning in 17th-century terms that does not apply to Vasa. However, the basic idea of a design that was reworked while the ship was being built is entirely appropriate. The significant changes that can be observed in the ship itself are the increase in width over the contract specification, the lengthening of the sterncastle decks and cabins, and the relocation of the mizzenmast. The extension of the sternpost may be a design change, although it could be result of a timber that was too short, although there are associated changes in the deck structure that suggest that this is a design alteration. We do know that Vasa's sister, Äpplet, is about 1 meter wider overall than Vasa and has a higher sterncastle, so the increase in stern height may well be a design alteration. There is no indication of an increase in height at the bow, there is no extension of the stem..Thank you very much, Fred, for all the detailed information about the hull shape. As it is not possible to verify all possible variants in one "deal", so I will most likely nevertheless check the verlanger option first, but not in the classic scenario, i.e. the reworking of an already completely built hull, but rather of the variety of a dramatic change of the design concept already after the start of construction at some stage, with the building material already prepared for the original variant, as you write about it. The inappropriate, too-low run of the line of greatest breadth symmetrically on both sides, the extended stem post, the extended stern post and perhaps something else, is already a number of indications that can hardly be easily ignored (for greater clarity: it's for the assumption that Vasa is a reworked still during construction of a smaller ship of the whole, complete contract, if I remember the circumstances correctly).

However, I am away from home for a few more days and do not have access to all the material I should be consulting while making this attempt. I apologise for this delay.

It may even be possible to write a doctoral dissertation on the subject, but in practical terms it is probably the shortest way to say that a ship of 'similar' size (and sporting tumblehome) should not be submerged more than two-three feet below the line of greatest breadth (admittedly, one of the royal French ordinances of the second half of the 17th century provided for an equalisation of these levels, but it is not entirely clear whether this should be interpreted quite literally, and even less whether the designers complied with this ordinance in such a literal way at all, especially as they must have been aware of its potentially very dangerous consequences).

.

I think that it is important to distinguish between two different moments in the design development. I believe that because Hybertsson had not previously built a ship with multiple gundecks (as far as we know), he had no good starting point for Vasa's design other than his experience with ships with a single gundeck. So his initial design, as intended in the contract, may well have been a vertically "stretched" version of a successful earlier design, such as Tre Kronor, the large single-decker he was completing in 1625, but it should be emphasized that the initial design was an integrated concept (even if a bad one), not simply a single decker with a deck added.

The second moment was the alteration in width and other details after construction began. I believe it is possible to identify the specific canges made, and even to determine at what point in the construction the changes were made. For example, I think that it is clear that the increase in breadth was decided after the stem and transom had been erected. The change in the configuration of the stern is in two phases, both associated with the construction of the decks and internal accommodation.. The lengthening of the sternpost is associated with the addition of a secondary wing transom and an increase in the headroom in the after end of the orlop, while the extension forward of the cabins has to have occurred later in the construction of the upper parts of the sterncastle.

One of the interesting aspects of these changes can be seen in Äpplet. That ship has the upward extension of the transom incorp0rated as an integrated feature of the design rather than as an alteration of the structure, and the increase in breadth appears to extend all the way to the transom, giving Äpplet a different shape towards the stern.

Fred

Warning: Sea Story follows

The modern term in American English for verlanger is "jumboed", from the colloquial term "jumbo" which means "extra large". It essentially means cutting a ship in half and inserting an extra center section of the ship to make it longer. This was done to may T2 tanker ships after WWII to make the more useful after the war, instead of building new ships which was more expensive. Unfortunately, the welding of the T2 tankers was not very strong, given that the technology was new, and those tankers which were jumboed frequently broke in half in bad seas. The radio officer on one of my ships, the S.S. Arco Alaska, related to me that he was supposed to work on board one of those modified WWII relics, and was going to fly down to Texas to board the ship. Luckily for him, he missed his plane flight, the only flight he had EVER missed in his entire life, and the ship broke in half in the Gulf of Mexico, taking all hands with it to the bottom.

My thanks to all those contributing to one of the most interesting research posts found in this forum.

The modern term in American English for verlanger is "jumboed", from the colloquial term "jumbo" which means "extra large". It essentially means cutting a ship in half and inserting an extra center section of the ship to make it longer. This was done to may T2 tanker ships after WWII to make the more useful after the war, instead of building new ships which was more expensive. Unfortunately, the welding of the T2 tankers was not very strong, given that the technology was new, and those tankers which were jumboed frequently broke in half in bad seas. The radio officer on one of my ships, the S.S. Arco Alaska, related to me that he was supposed to work on board one of those modified WWII relics, and was going to fly down to Texas to board the ship. Luckily for him, he missed his plane flight, the only flight he had EVER missed in his entire life, and the ship broke in half in the Gulf of Mexico, taking all hands with it to the bottom.

My thanks to all those contributing to one of the most interesting research posts found in this forum.

- Joined

- Apr 2, 2021

- Messages

- 601

- Points

- 198

Very Interesting discussion. I’ve been to the Vasa Museum and my take away then was it appeared more attention was given the prow and sterncastle design which put so much “Baroque Warship” into the design that the symmetry and stability of the entire ship was compromised. It looked like form vs function was at play. Fred and Waldemar…thanks for the insightful info!

Like everyone else, I am thoroughly enjoying this exchange. Among us, I think it’s fair to say that Waldemar stands among a very few with both a broad and nuanced understanding of these 17th C. design principles. His arguments are always compelling, and I continue to learn so much from his explorations. That Mr. Hocker shares his particular insights so freely with this community, fulfills what I think is the noblest calling of researchers and historians; to share, to elucidate and educate, and to acknowledge that there may yet be an angle of this problem that he/she has not yet considered. I have not often seen that degree of humility and honesty in the academic community. That’s a pretty cool thing, and thank you Mr. Hocker for making all of this so accessible.

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

Happy to be a part of this discussion! There are a lot of knowledgeable people in the world who are not professional academics, and as a professional academic (formerly a tenured professor of archaeology, before I moved to the museum world), I am aware that some (not all) of my learned colleagues do not take people with practical knowledge seriously. Since I started out as a wooden shipwright and machinist before I was an archaeologist, I hope I am smarter than that.

This discussion has not only been entertaining, it is also helping us to refine our approach to the study of Äpplet, now that we have access to the wreck. We can, for example, investigate if the same error in max breadth was built into that ship, although preliminary measurements suggest that it was not, they corrected the error by incorporating many of the changes made to Vasa as integrated parts of the initial design for Äpplet, allowing for the inherent limitations of rough-shaped timbers already in hand when construction started.

I will add in answer to WDO that understanding the sinking is not as simple a question as most people think, and one of the problems that has dogged the investigation of the loss in modern times is that almost everyone who has looked at it is looking for a monocausal explanation, a "smoking gun", since that is how most modern History Channel-type documentaries approach this kind of problem. So, not surprisingly, people who are interested in sculptures believe that the problem is too many sculptures, people who are interested in guns believe that there are too many guns, and there has even been a person interested in provisioning who published an article claiming that the sinking was caused by loose casks of provisions rolling around in the decks! No evidence for loose casks actually found, if you were wondering.

In fact, modern accident investigation is based on the premise that accidents result from a chain of errors in most cases, not a single cause. In Vasa's case, the ship was certainly a bad ship (and Waldemar has identified a previously unnoticed contributing factor to its badness), but that is not the only or even proximate cause of the accident. The navy knew the ship was bad and sent it to sea anyway, and the captain made a fundamental error in sailing the ship (leaving the lower gunports open) even though he was the person who had informed the admiralty that the ship was dangerous. In modern boards of inquiry and legal suits, one often speaks of the "chain of causality" in assessing liability. I have recently discussed the Vasa case with an admiralty law barrister who specializes in these kinds of cases, and she agrees that a modern court would find a clear chain of causality that starts with a bad design but also includes an unfavorable decision-making environment which led the admiralty to hesitate to tell the king that there was a problem. We are working on a publication of all of this, to explain how the accident occurred and how blame might be apportioned in a modern context (which is surprisingly close to how it was understood in 1628), and Waldemar's discovery will help to clarify one of the contributing causes of the loss.

So I will keep listening to modelbuilders and sailors and boatbuilders, because it pays off!

Fred

This discussion has not only been entertaining, it is also helping us to refine our approach to the study of Äpplet, now that we have access to the wreck. We can, for example, investigate if the same error in max breadth was built into that ship, although preliminary measurements suggest that it was not, they corrected the error by incorporating many of the changes made to Vasa as integrated parts of the initial design for Äpplet, allowing for the inherent limitations of rough-shaped timbers already in hand when construction started.

I will add in answer to WDO that understanding the sinking is not as simple a question as most people think, and one of the problems that has dogged the investigation of the loss in modern times is that almost everyone who has looked at it is looking for a monocausal explanation, a "smoking gun", since that is how most modern History Channel-type documentaries approach this kind of problem. So, not surprisingly, people who are interested in sculptures believe that the problem is too many sculptures, people who are interested in guns believe that there are too many guns, and there has even been a person interested in provisioning who published an article claiming that the sinking was caused by loose casks of provisions rolling around in the decks! No evidence for loose casks actually found, if you were wondering.

In fact, modern accident investigation is based on the premise that accidents result from a chain of errors in most cases, not a single cause. In Vasa's case, the ship was certainly a bad ship (and Waldemar has identified a previously unnoticed contributing factor to its badness), but that is not the only or even proximate cause of the accident. The navy knew the ship was bad and sent it to sea anyway, and the captain made a fundamental error in sailing the ship (leaving the lower gunports open) even though he was the person who had informed the admiralty that the ship was dangerous. In modern boards of inquiry and legal suits, one often speaks of the "chain of causality" in assessing liability. I have recently discussed the Vasa case with an admiralty law barrister who specializes in these kinds of cases, and she agrees that a modern court would find a clear chain of causality that starts with a bad design but also includes an unfavorable decision-making environment which led the admiralty to hesitate to tell the king that there was a problem. We are working on a publication of all of this, to explain how the accident occurred and how blame might be apportioned in a modern context (which is surprisingly close to how it was understood in 1628), and Waldemar's discovery will help to clarify one of the contributing causes of the loss.

So I will keep listening to modelbuilders and sailors and boatbuilders, because it pays off!

Fred

.

Thank you very much for your very stimulating comments. They all must have made me get down to work on this project sooner, despite the ongoing state of not having access to my materials left at home. Anyway...* * *

... I am becoming more and more convinced that the Vasa 1628 was built from recycled timber, specifically intended originally for another, much smaller ship (unless information comes to light that rules out this possibility without any doubt).

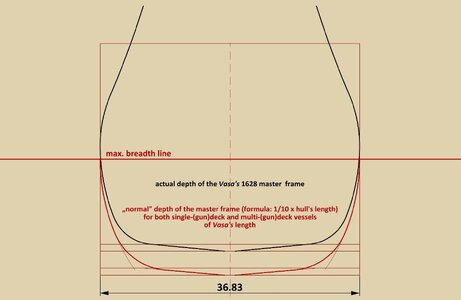

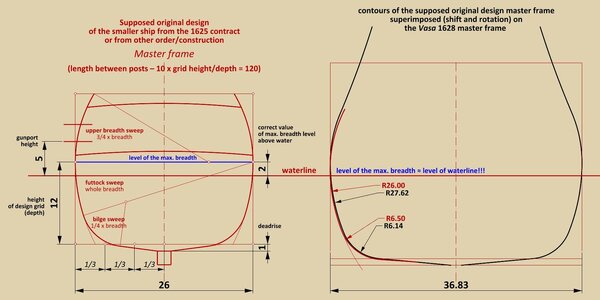

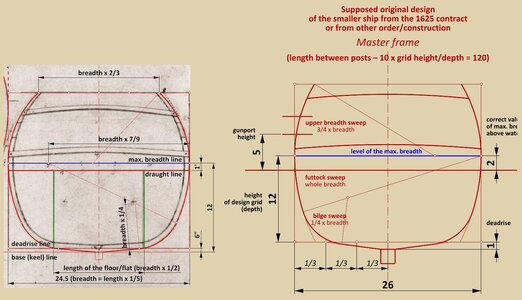

Well, looking for the reasons for the too low level of the line of maximum breadth and at the same time insufficient depth of the submerged part of the hull in relation to its above-water part, I checked the variant, basically suggested by Fred @fred.hocker, that is, for the already prepared building material, but with the consideration that for a much smaller ship. As a result, I was able to produce such a realistic, presumably original design, and in such a way that it not only has the quite standard design parameters for the period (see attached diagram). It also so happens that identical main dimensions and proportions were also present in an authentic ship from 1627 with proven successful (or at least good enough) sea qualities, specifically the flagship of the fleet of the then Swedish opponent.

As can be seen in the diagram, the conformity of the curves is very good, and could be even better, taking into account that the whole, complete contour is made up of several separate elements with possibly some slack in position relative to each other. However, the most important thing is that this particular building material with specific and basically already unchanging curves, if it allowed a fairly free increase in the breadth of the hull, did not at the same time give chance for any significant increase in height (depth) below the line of maximum breadth. Which could perfectly explain both the insufficient depth of the Vasa 1628 and the too low level of the maximum breadth line.

Quite a few structural clues also suggest and at the same time seem to confirm such a variant, i.e. the use of timber material originally intended for a smaller ship:

– a keel composed of as many as four elements (instead of the normal rather smaller number),

– reinforcement of the keel by adding a false keel on its upper edge (apparently to increase its too-small cross-section),

– extended stern post,

– a stempost made up of as many as three elements (i.e. also suggesting the possibility of its extending),

– very small scantlings of frame components, especially floor timbers (sided dimensions of only about 3/4 foot; measured on the publicly available sketch), too small also for a smaller ship, let alone for a giant like Vasa 1628.

Again, it would also be worth comparing all this with Äpplet, but I don't want to stretch the string too much...

.

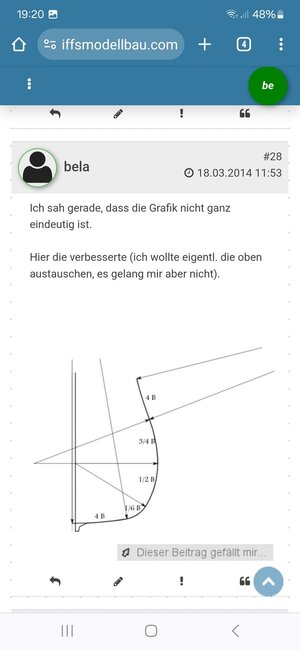

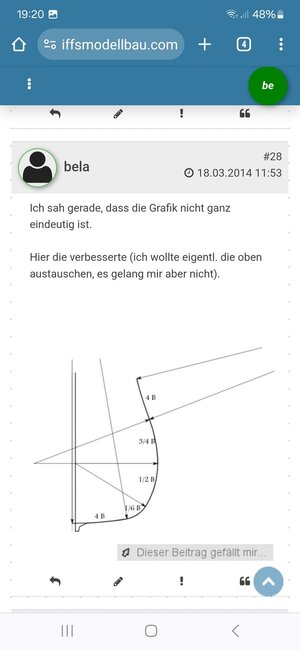

After I found the inspiration to read into this thread in more detail today, I noticed a nice correspondence with one of my own studies on Vasa.

I'm attaching a screenshot.

Since I didn't have a good line plan at my disposal, I interpreted the flat and the bilge sweep a little differently

greeting

Bela

I'm attaching a screenshot.

Since I didn't have a good line plan at my disposal, I interpreted the flat and the bilge sweep a little differently

greeting

Bela

.

Hi Bela,If the conjecture described in my last post (#31) proves to be correct, then in the specific case of the Vasa 1628, both our attempts to find proportions for the individual sweeps and the geometric design of the master frame in relation to the main, final dimensions of this ship are simply pointless and even downright misleading. On the other hand, it may be a good indication of the degree of flexibility that shipwrights of the time exercised.

.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

Sorry to disappoint you, Waldemar, but Vasa was not begun as a smaller (shorter, lower) ship and then extended in length or height, although the design may have its origins in experience with smaller ships, which could lead to odd proportions. Nor is Vasa built with timbers originally cut for a smaller ship. It is definitely not built with recycled timber. Here is just some of the evidence.

Archaeological:

1. We know what the dimensions of the next size smaller ship look like, from a specification sent to the king from the master shipwright in the autumn of 1625. This is for Tre Kronor, which was a large, single-gundeck ship launched that autumn, the last ship Hybertsson built before Vasa. In this specification, we can see that all of the timbers are smaller than the corresponding timbers in Vasa. For example, the keel of Tre Kronor is 21 inches moulded and sided amidships, but Vasa's keel is 23-24 inches at its largest.

2. Vasa's keel is not at all undersized by the standards of the time. If we look at the proportions quoted by Witsen (1671), he indicates that the keel of a ship in this size range should be of three or four pieces, depending on the timber available. The cross section should be 1 inch for every foot of length over the stems, or 1/77 of the length over stems (11 inches in an Amsterdam foot). For Vasa, which is about 160 feet over the stems, give or take a few inches, the keel should thus be about 24 inches, which it is. The square cross section is typical of Dutch shipbuilding in the 17th century.

3. The keel is about 38.4 m long. If you remove any of the four pieces of which it is made, it is still too long for the smaller ships intended under the same contract.

4. The hog on top of the keel is primarily there to allow the hollow garboard. It allows the use of straight floor timbers without chocks under them, and is a solution seen in other Dutch ships of the period. It also adds stiffness, but it s not an afterthought, it is part of the basic structural design.

5. The frame timbers vary quite a lot in sided dimension (typical Dutch practice). The smallest we have measured is about 20 cm, but most are 25 cm or more, with the average falling around 26. The largest are almost 50 cm sided. If one compares the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia, built the same year in Amsterdam and of very similar displacement, the frame timbers are more or less the same size. The frame timbers in Äpplet are of similar size. Archaeological evidence suggests that Dutch builders did not conventionally use massive, wide frame timbers, and their frames are usually sided less than the frame timbers in equivalent English ships but greater in number. So the frame timbers are what one would expect in a Dutch ship of this size and date.

6. The stem is made of multiple pieces, but not is a way that suggests it was extended, only that several pieces were needed to make up the full curvature from the available timber. If the uppermost piece is removed, the resulting stem has too little overall curvature and would have to be set at a higher angle to be able to get a bow that is not a shallow dish.

7. The sternpost does have a piece at the upper end that looks like an extension, but it is not very long, and seems to be connected to the raising of the level of the lower gundeck at the stern, in the area of the gunroom. This upward extension of the transom and associated deck appears to be a modification made during construction, possibly to increase working headroom in the after end of the orlop, where two large stern chasers were mounted. This upward extension is also above the maximum breadth of the transom fashion pieces.

8. There is no evidence in any of the timbers that they have seen any previous use, so they are not recycled.

Historical evidence:

1. The contract under which Vasa was built called for four new ships, two large and two small. The larger should be 128 or 135 feet on the keel (there are two version of the contract, the second on, 128 feet, seems to be the operative one) and 34 feet maximum beam. The smaller should be the same size as an existing ship, Gustavus, although Hybertsson later suggested Tre Kronor as the model. Tre Kronor's keel was 108 feet. Vasa's actual keel length is just over 129 feet (depending on how you measure) and so agrees pretty well with the contract for the larger class.

2. From the earliest contract negotiations in the autumn of 1624, the discussion of new construction centered on two classes of ships, a larger and smaller, with a substantial difference in cost. The larger would cost more than twice as much as the smaller, too great a differnce to be accounted for in ships that differed only in 20 feet of length on the keel. The larger class was expected to be much larger vessels, which would need to be much wider and/or taller to account for the cost difference.

3. There was no smaller ship for which timber had been cut that could have been adapted to build Vasa. As noted above, all of Vasa's timbers are smaller than those Hybertsson had at his disposal for the smaller class (the Tre Kronor specification). We know this because:

4. In the correspondence between Hybertsson and the king (through vice admiral Klas Fleming) in the autumn of 1625, the builder reported several times that during 1625 he had bought/harvested and rough shaped the timber for two ships, a large ship and a small ship, according to the contract, and that he had no other timber on hand. The contract specified that the large ship should be built first. Hybertsson also specifically said that he could not build a larger ship with the smaller timber. But he thus had on hand the timber needed for the larger ship, so there was no need to use the smaller timbers.

This does not change the fact that the design is seriously flawed, but it was probably flawed already at the conceptual stage. As noted already in the inquest in 1628, the ship has too little draught and thus dsiplacement to carry its upperworks. Waldemar has shown above that if one starts with the timbers for the original specification, that one can make the ship wider but not significantly deeper. I would maintain that this means that the original design concept started with a flawed premise regarding the underwater part of the hull, and because the framing timber was rough shaped as part of the harvesting process, this initial decision limited the possibilities for improving the design with the existing timber. Waldemar's reconstruction above shows pretty clearly that the basic design before widening is not a good one.

All of this is in the back of my mind every time a visitor tells me how beautiful the ship is. My shipwright's brain is saying "sure, but in naval architectural terms, it's a dog." It started as a dog, and attempts to improve it just made it a fatter dog.

Fred

Archaeological:

1. We know what the dimensions of the next size smaller ship look like, from a specification sent to the king from the master shipwright in the autumn of 1625. This is for Tre Kronor, which was a large, single-gundeck ship launched that autumn, the last ship Hybertsson built before Vasa. In this specification, we can see that all of the timbers are smaller than the corresponding timbers in Vasa. For example, the keel of Tre Kronor is 21 inches moulded and sided amidships, but Vasa's keel is 23-24 inches at its largest.

2. Vasa's keel is not at all undersized by the standards of the time. If we look at the proportions quoted by Witsen (1671), he indicates that the keel of a ship in this size range should be of three or four pieces, depending on the timber available. The cross section should be 1 inch for every foot of length over the stems, or 1/77 of the length over stems (11 inches in an Amsterdam foot). For Vasa, which is about 160 feet over the stems, give or take a few inches, the keel should thus be about 24 inches, which it is. The square cross section is typical of Dutch shipbuilding in the 17th century.

3. The keel is about 38.4 m long. If you remove any of the four pieces of which it is made, it is still too long for the smaller ships intended under the same contract.

4. The hog on top of the keel is primarily there to allow the hollow garboard. It allows the use of straight floor timbers without chocks under them, and is a solution seen in other Dutch ships of the period. It also adds stiffness, but it s not an afterthought, it is part of the basic structural design.

5. The frame timbers vary quite a lot in sided dimension (typical Dutch practice). The smallest we have measured is about 20 cm, but most are 25 cm or more, with the average falling around 26. The largest are almost 50 cm sided. If one compares the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia, built the same year in Amsterdam and of very similar displacement, the frame timbers are more or less the same size. The frame timbers in Äpplet are of similar size. Archaeological evidence suggests that Dutch builders did not conventionally use massive, wide frame timbers, and their frames are usually sided less than the frame timbers in equivalent English ships but greater in number. So the frame timbers are what one would expect in a Dutch ship of this size and date.

6. The stem is made of multiple pieces, but not is a way that suggests it was extended, only that several pieces were needed to make up the full curvature from the available timber. If the uppermost piece is removed, the resulting stem has too little overall curvature and would have to be set at a higher angle to be able to get a bow that is not a shallow dish.

7. The sternpost does have a piece at the upper end that looks like an extension, but it is not very long, and seems to be connected to the raising of the level of the lower gundeck at the stern, in the area of the gunroom. This upward extension of the transom and associated deck appears to be a modification made during construction, possibly to increase working headroom in the after end of the orlop, where two large stern chasers were mounted. This upward extension is also above the maximum breadth of the transom fashion pieces.

8. There is no evidence in any of the timbers that they have seen any previous use, so they are not recycled.

Historical evidence:

1. The contract under which Vasa was built called for four new ships, two large and two small. The larger should be 128 or 135 feet on the keel (there are two version of the contract, the second on, 128 feet, seems to be the operative one) and 34 feet maximum beam. The smaller should be the same size as an existing ship, Gustavus, although Hybertsson later suggested Tre Kronor as the model. Tre Kronor's keel was 108 feet. Vasa's actual keel length is just over 129 feet (depending on how you measure) and so agrees pretty well with the contract for the larger class.

2. From the earliest contract negotiations in the autumn of 1624, the discussion of new construction centered on two classes of ships, a larger and smaller, with a substantial difference in cost. The larger would cost more than twice as much as the smaller, too great a differnce to be accounted for in ships that differed only in 20 feet of length on the keel. The larger class was expected to be much larger vessels, which would need to be much wider and/or taller to account for the cost difference.

3. There was no smaller ship for which timber had been cut that could have been adapted to build Vasa. As noted above, all of Vasa's timbers are smaller than those Hybertsson had at his disposal for the smaller class (the Tre Kronor specification). We know this because:

4. In the correspondence between Hybertsson and the king (through vice admiral Klas Fleming) in the autumn of 1625, the builder reported several times that during 1625 he had bought/harvested and rough shaped the timber for two ships, a large ship and a small ship, according to the contract, and that he had no other timber on hand. The contract specified that the large ship should be built first. Hybertsson also specifically said that he could not build a larger ship with the smaller timber. But he thus had on hand the timber needed for the larger ship, so there was no need to use the smaller timbers.

This does not change the fact that the design is seriously flawed, but it was probably flawed already at the conceptual stage. As noted already in the inquest in 1628, the ship has too little draught and thus dsiplacement to carry its upperworks. Waldemar has shown above that if one starts with the timbers for the original specification, that one can make the ship wider but not significantly deeper. I would maintain that this means that the original design concept started with a flawed premise regarding the underwater part of the hull, and because the framing timber was rough shaped as part of the harvesting process, this initial decision limited the possibilities for improving the design with the existing timber. Waldemar's reconstruction above shows pretty clearly that the basic design before widening is not a good one.

All of this is in the back of my mind every time a visitor tells me how beautiful the ship is. My shipwright's brain is saying "sure, but in naval architectural terms, it's a dog." It started as a dog, and attempts to improve it just made it a fatter dog.

Fred

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

As a query to Bela and Waldemar, how do the proportions of the main sweeps look if you use the specified keel length and maximum breadth as the reference dimensions instead of the actual measurements? So 128 feet (38.016 m) LOK and 34 feet (10.098 m) moulded beam? These are the only two measurements given in the contract since Dutch methods scaled everything from these dimensions. Length over stems, for example, was usually 5/4 of LOK, which works out to 160 feet, nearly spot on for the hull as built.

Fred

Fred

It started as a dog, and attempts to improve it just made it a fatter dog.

I love this sentence

It started as a dog, and attempts to improve it just made it a fatter dog

.

Thank you very much, Fred. It was with a kind of, hmm... strange consternation that I found that the handful of new or previously unknown facts you have just given confirm rather than contradict the hypothesis of using timbers intended for a smaller ship in the construction of the Vasa 1628, and the proverbial catch is probably in their different interpretation. Here is my current perspective on the matter.Sequence of events:

— early 1625 – contract for, among other things, the construction of four ships, two larger and two smaller, with the larger ship to be built first,

— 1625 – gathering timber for one larger and one smaller ship; start of Tre Kronor construction,

— 1626 – construction completed and Tre Kronor taken into service; primarily according to the provisions of the contract, but also the findings of Björn Landström, as well as the breadth of the hull (33' 8"), it should rather be considered the larger ship (at least in the contract meaning), for the construction of which a set of timbers intended for the larger ship was used.

Even earlier, in the autumn of 1625, Hybertsson explains to the authorities that he cannot build a larger ship from smaller timbers. To my mind, he does this in response to a question or demand from the authorities to proceed with the construction of a second larger ship from the contract, in addition to the Tre Kronor. In the end, however, fully aware of the high risk of such an undertaking and even possible disaster, Hybertsson succumbs to the apodictic authorities and proceeds to build Vasa in 1626, with his remaining set of smaller timbers originally intended for a smaller ship. Shortly after starting this construction, Hybertsson falls ill with a then dangerous illness and soon dies.

Indeed, such an explanation presents a rather simple and logical cause-and-effect relationship, but in practice just such in real life are almost always correct.

Design rationale:

First of all, the actual hull depth of Vasa 1628 (that is, below the actual maximum breadth line) is only about 12 feet, instead of the more proper depth for the hull length of this ship, which should normally be about 15–16 feet. This is a huge difference. Is it possible for an experienced shipwright to be ignorant of the basic and usually quite strictly enforced rule that the depth should be 1/10th of the hull length? Even worse, that through his alleged inexperience he consciously and deliberately reduced this depth, because of the extra deck, however against elementary logic, because such an additional deck inevitably results in a heavier and taller ship? I categorically reject this possibility, as it would basically have to mean that Hybertsson was not qualified to design ships at all, not just multi-deck ships. In my opinion, only extraordinary circumstances, such as incredible pressure from an incomparably stronger contract partner, could have forced Hybertsson to agree to such a drastic move.

For the sake of brevity, I think I will dispense with referring to each and every point raised on the grounds that they are essentially, for example, neutral (e.g. a slightly too long keel after the removal of the fourth element) or the result of rather individual interpretation. For example, one could of course say that the stern post was lengthened to allow for some particular interior arrangement, but one could just as well say that some particular interior arrangement was only made possible by first lengthening the stern stern to the height normally envisaged for a ship of that size. It's like a bit of a quadrature circle issue, rather impossible to authoritatively resolve.

It is also almost obvious that a set of timbers intended for a smaller ship, but eventually used for a larger one, had to be supplemented with some additional timbers, already able to at least partially correspond with their scantlings to the size of the ship.

It is worth quoting, for comparison, some specific contract dimensions of a few ships of this period from the Baltic area – Danish and Swedish in particular:

Length between posts | Keel length | breadth | depth | Stempost rake | Thickness of floor timbers | |

| Fides 1613 | 124 | 90 | 30 | 11 | 30 | 12 inches |

| Hummeren 1623 | 107 | 80 | 26 | 6 | 23 | 11 inches |

| König David 1625 (measured) | 120 | 26 | 14 | |||

| Göteborg small design 1631 | 120 | 91 | 27 | 12 | 11 inches | |

| Göteborg medium design 1631 | 138 | 106 | 33 | 15 | 14 inches | |

| Göteborg large design 1631 | 168 | 130 | 40 | 16 1/2 | 15 inches |

First of all, it is clear that for smaller ships, i.e. those in the roughly 120-foot length category, 11–12 inches thick floor timbers were normally required, which is what was mostly used on Vasa 1628. For large ships, in the Vasa size category, 14–15 inches thick floor timbers are already expected. And this data is taken from the Swedish shipyard in Göteborg with only a few years of chronological interval.

The uncharacteristically thick reinforcements inside the Vasa's hull (riders), taking up such valuable space, as was pointed out during the trial conducted, can also be seen as some kind of attempt by the builders to compensate for the supposed or actual weakness of the scantlings of the frame timbers.

4. The hog on top of the keel is primarily there to allow the hollow garboard. It allows the use of straight floor timbers without chocks under them, and is a solution seen in other Dutch ships of the period. It also adds stiffness, but it s not an afterthought, it is part of the basic structural design.

I must honestly say that this is not an entirely understandable explanation for me. The keel of the Vasa 1628 was (indeed quite typical) about 24 inches high, but only together with a board of about 1.5 inches thick applied to it. However, just why deliberately use a keel lower than the required height, or even cut it down to a lower height in order to raise it later with a board, with the same final result (in terms of dimensions).

6. The stem is made of multiple pieces, but not is a way that suggests it was extended, only that several pieces were needed to make up the full curvature from the available timber. If the uppermost piece is removed, the resulting stem has too little overall curvature and would have to be set at a higher angle to be able to get a bow that is not a shallow dish.

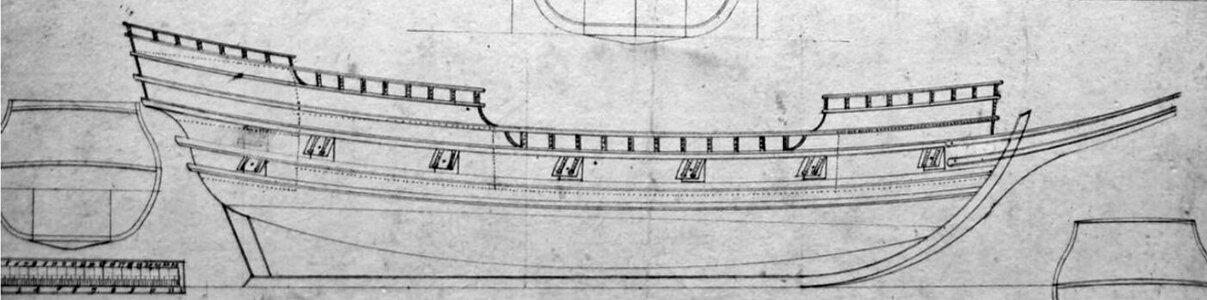

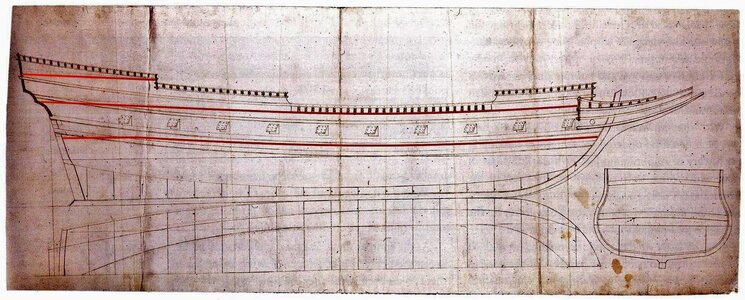

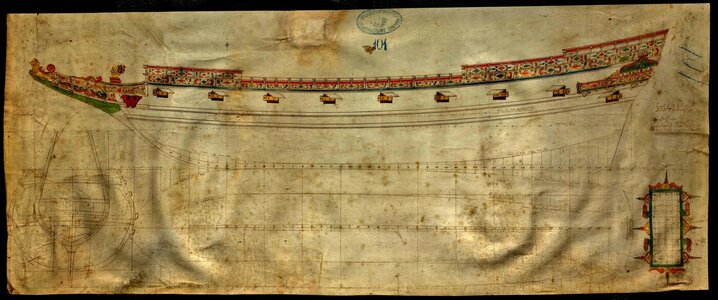

Below are some graphic examples of authentic designs from the period, characterised by a large stempost rake and at the same time its small curvature (i.e. large radius), giving the effect, in my perception, of just such a shallow dish. The first two ships in the table above also display quite large stempost rake combined with a low, because single-deck silhouette of the ship.

Waldemar's reconstruction above shows pretty clearly that the basic design before widening is not a good one.

Not really sure of the meaning, however, just to be sure, I would like to add that my proposed 'supposed original design' for the smaller ship, shown in the diagram in the previous post, is, both in terms of dimensions and proportions, almost identical (within 1–2 feet) to König David 1625, Göteborg 1631 (smaller design) and the standard Danish defensionsskib design from around 1630. In addition to this, the contours and geometric design in general of the master frame shown are also almost identical to the latter design made in the Dutch style then practised in Sweden, including by Hybertsson, as can be seen from the comparison below:

As I become more and more aware of all this, I no longer regard Hybertsson as an inept shipwright, au contraire – as an experienced designer capable of building successful ships, irrespective of the number of decks, but who, in the case of Vasa 1628, had to succumb to unusually strong pressure from the authorities to rush the construction of this particular ship from inadequate, but already accumulated material and ready for immediate use, in order to satisfy the will of an impatient ruler wishing to receive his double-decked marvel as soon as possible.

PS.

I am very sorry for the unfortunate use of the term 'recycled', but I hope that the context of the whole post leaves no doubt as to its intended meaning.

.

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

I do not think that Hybertsson was an incompetent designer. After all, he had spent over 20 years in service to the Swedish state designing ships, and the vessels he built were generally considered good vessels. Otherwise, the crown would not have signed a contract with him in 1624/1625 to maintain the fleet and build four new ships. However, as far as we can see from the list of vessels he had built, he had never built a ship with multiple gundecks. All of his previous designs were for ships with a single gundeck, which was the typical type ordered by the navy in the first quarter of the 17th century. Any ship carrying large deck weights is a design challenge, but a single gundeck allows a wider range of solutions that can all work. Multiple gundecks complicate the design challange, and it was quite common in this period, before the development of the mathematical tools that allow the analysis of a paper design, that multi-deck warships, even those built by well-known and established designers, did not perform well when first commissioned and had to be altered to improve their stability. The increasingly common practice of overgunning made the problems even worse.

The timeline for Vasa's design and construction is somewhat different than what Waldemar proposes (Waldemar's proposal largely echoes the hypothesis of Landström, writing in 1980), and there are some important differences in what the original sources say. It is also important to realize that Tre Kronor was not the first ship built under the contract signed in the winter of 1624/1625, as Landström and some others have supposed (a misconception that can be found in much of the older literature, although already corrected by Borgenstam and Sandström by 1984). It was actually the last ship built under the previous contract, involving Hybertsson and his previous partner Monier. The contracts themselves and the surviving correspondence make this clear. Here is what the documents say (I can provide archive references for those who want them):

1. In December 1624 and January 1625, Hybertsson (and in the 1625 version his partner Arendt de Groote) signed a contract to maintain the hulls of the fleet (rigging was contracted to a different party) and to build four new ships. Two of these would be smaller vessels, costing 16000 dalers each, modelled after an existing vessel, Gustavus (completed in 1623), although no specific dimensions are given. The other two vessels, costing 40 000 or 42 000 dalers each, would be either 135 or 128 feet long on the keel and 34 feet maximum moulded beam. This contract would come into force in January 1626, and until then Hybertsson would be operating under the old contract (in which he became a partner in 1622). Under this contract, the first ship to be built would be one of the larger class.

2. During 1625, Hybertsson began buying in timber for existing projects in the navy yard and for the new ships to be built under the old contract. This included sending carpenters out into Swedish forests, under the direction of a master shipwright, Johan Isbrandtsson, to fell and roughly shape timbers for the new ships (as confirmed by the surviving account books from 1625). Arendt de Groote bought rough-sawn plank in foreign ports, such as Riga, Königsberg and Amsterdam. Hybertsson also built the last ship ordered under the previous contract, which we can determine is Tre Kronor. This ship was launched late in 1625 (after October 1).

3. In September 1625, Hybertsson communicated to the king via Klas Fleming that he had now accummulated enough timber of the right sizes to build one large ship and two smaller ones according to the contract, and that he had the last ship of the previous contract now ready to launch. The only ship launched in autumn 1625 in Stockholm was Tre Kronor. Thus Tre Kronor is neither the larger nor the smaller ship referred to in the 1625 contract. In addition, Hybertsson suggested that the ship he now had ready to launch would be a good model for the smaller ship of the 1625 contract, and he provided a detailed list of dimensions for this ship, both its overall dimensions and scantlings of major timbers. We thus have a detailed picture of how Tre Kronor was actually built. This list indicates that the ship was 108 feet LOK, with a keel 21 inches square amidships, stem 10 inches thick/sided and sternpost 8 inches thick/sided, floor timbers 12 inches moulded, and riders 16 inches moulded. Sided dimensions of the frames are not reported, probably because these varied (typical Dutch practice). These are the dimensions one would should expect for the smaller ship of the 1625 contract, since Hybertsson was suggesting these edimensions for exactly this purpose, and Tre Kronor is thus neither the larger ship built fo the the 1625 contract nor the model for it.

4. In October 1625, ten naval vessels were lost in a storm at the entrance to Riga bay.

5. In early November 1625, the king replied to Hybertsson, via Fleming, that the navy needed to be rebuilt quickly and that Hybertsson should depart from the contract and build two ships with the timber he had on hand, to a new specification, which the king provided with the letter. He specifically noted that this was a new specification for the smaller type ordered earlier in the year. This called for a ship of 120 feet on the keel with a bottom breadth of 24 feet and similar or slightly larger scantlings to Tre Kronor. The keel, for example, would still be 21 inches square, but the stem would be 15 inches sided and the sternpost 12 inches. There were also specific instructions (very well considered, for the most part) about details of fastening, timber overlaps, etc.

6. Hybertsson replied in early January that he could not follow the king's command, since he could not build a larger vessel (meaning the new 120 foot LOK spec) with the timber already cut for the smaller type, and could not cut down the timber for the larger contract type without significant economic harm to himself. He also reported that he had conducted a detailed survey of the timber he had on hand, and that this was sufficient to build a smaller ship and a larger ship. He does not explain why he thought in September that had anough timber for two smaller ships but now only enough for one, although it could be that some timber had been consumed in fitting out Tre Kronor or in repairing ships damaged in the autmun storms. But in any case, he believed that in January, before he had laid the keel for Vasa, that he had adequate timber for either a larger or smaller ship of the 1625 specification.

7. The king replied that Hybertsson should follow his new instructions, but if "he could not or would not," he was to follow the terms of the contract as signed. This meant to build the a ship of the larger class (128 feet LOK) first.

8. In early March 1626, Hybertsson was called to a meeting with the chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, to account for his actions. At this meeting, he explained the same issues he had tried to explain to the king, and that he had followed the terms of the contract (as the king had eventually agreed) and that the keel for the first vessel had been laid (thus probably in later February or early March), but noted that it would differ slightly from the specification. We can see that the actual keel length differs slightly in length from the spec for the larger ship, by less than 2%.

9. After the keel was laid, there was no further discussion in the official correspondence about the size of the ship or its specification, nor any change orders. What discussion there was of Vasa largely focused on the armament plan, which was a debate that covered a wide range of possibilities and was not settled until after the hull was complete. The changes made to the ship during construction do not seem to have required royal approval, but could have been initiated or approved by the navy's "project officer", a senior captain supervising the private contractors at the navy yard.

If we compare the actual dimensions of Vasa's timbers to the specification for Tre Kronor, the proposed model for the smaller ship, and to the king's proposed "medium" ship of 120 LOK, we can see that almost all of the actual timber dimensions in the ship as built, from the very first timber laid down, are measurably larger than the timber used in Tre Kronor (and thus the spec for the smaller ship class of the 1625 contract) or specified for the king's altered spec. It is thus very difficult to see how one could say that Vasa is built from timbers originally designed/cut for a smaller ship. Which smaller ship?

I would still agree that the design of Vasa is basically an enlargement of a design for a smaller vessel, since that is the starting point Hybertsson had in his experience.

As for the extreme pressure from the king, this is largely overdriven in some modern studies. There is no evidence that the king pushed Hybertsson to finish the ship ahead of schedule, and after the discussion of size in the autumn of 1625, the king eventually accepted Hybertsson's explanation of the limitations imposed by the timbers already cut, and allowed him to follow the terms as laid down in the contract without further interference. It then took about 18 months to complete the hull, which is not a rush job in a 17th-century shipyard run and manned by Dutch shipwrights.

Where the king's pressure did come to bear was on the supply of armament. The foundry in Stockholm was very slow in filling the order for an entirely new armament of 72 bronze guns, and Vasa sat idle for a year after the ship was substantially finished before there were enough guns to arm it. Gustav Adolf pulled a number of strings and interfered significantly to try to get the ship armed in time for the 1628 campaign season, a year after it should have been in service, and even then it sailed eight guns short of its mandated armament.

Fred

The timeline for Vasa's design and construction is somewhat different than what Waldemar proposes (Waldemar's proposal largely echoes the hypothesis of Landström, writing in 1980), and there are some important differences in what the original sources say. It is also important to realize that Tre Kronor was not the first ship built under the contract signed in the winter of 1624/1625, as Landström and some others have supposed (a misconception that can be found in much of the older literature, although already corrected by Borgenstam and Sandström by 1984). It was actually the last ship built under the previous contract, involving Hybertsson and his previous partner Monier. The contracts themselves and the surviving correspondence make this clear. Here is what the documents say (I can provide archive references for those who want them):

1. In December 1624 and January 1625, Hybertsson (and in the 1625 version his partner Arendt de Groote) signed a contract to maintain the hulls of the fleet (rigging was contracted to a different party) and to build four new ships. Two of these would be smaller vessels, costing 16000 dalers each, modelled after an existing vessel, Gustavus (completed in 1623), although no specific dimensions are given. The other two vessels, costing 40 000 or 42 000 dalers each, would be either 135 or 128 feet long on the keel and 34 feet maximum moulded beam. This contract would come into force in January 1626, and until then Hybertsson would be operating under the old contract (in which he became a partner in 1622). Under this contract, the first ship to be built would be one of the larger class.

2. During 1625, Hybertsson began buying in timber for existing projects in the navy yard and for the new ships to be built under the old contract. This included sending carpenters out into Swedish forests, under the direction of a master shipwright, Johan Isbrandtsson, to fell and roughly shape timbers for the new ships (as confirmed by the surviving account books from 1625). Arendt de Groote bought rough-sawn plank in foreign ports, such as Riga, Königsberg and Amsterdam. Hybertsson also built the last ship ordered under the previous contract, which we can determine is Tre Kronor. This ship was launched late in 1625 (after October 1).

3. In September 1625, Hybertsson communicated to the king via Klas Fleming that he had now accummulated enough timber of the right sizes to build one large ship and two smaller ones according to the contract, and that he had the last ship of the previous contract now ready to launch. The only ship launched in autumn 1625 in Stockholm was Tre Kronor. Thus Tre Kronor is neither the larger nor the smaller ship referred to in the 1625 contract. In addition, Hybertsson suggested that the ship he now had ready to launch would be a good model for the smaller ship of the 1625 contract, and he provided a detailed list of dimensions for this ship, both its overall dimensions and scantlings of major timbers. We thus have a detailed picture of how Tre Kronor was actually built. This list indicates that the ship was 108 feet LOK, with a keel 21 inches square amidships, stem 10 inches thick/sided and sternpost 8 inches thick/sided, floor timbers 12 inches moulded, and riders 16 inches moulded. Sided dimensions of the frames are not reported, probably because these varied (typical Dutch practice). These are the dimensions one would should expect for the smaller ship of the 1625 contract, since Hybertsson was suggesting these edimensions for exactly this purpose, and Tre Kronor is thus neither the larger ship built fo the the 1625 contract nor the model for it.

4. In October 1625, ten naval vessels were lost in a storm at the entrance to Riga bay.

5. In early November 1625, the king replied to Hybertsson, via Fleming, that the navy needed to be rebuilt quickly and that Hybertsson should depart from the contract and build two ships with the timber he had on hand, to a new specification, which the king provided with the letter. He specifically noted that this was a new specification for the smaller type ordered earlier in the year. This called for a ship of 120 feet on the keel with a bottom breadth of 24 feet and similar or slightly larger scantlings to Tre Kronor. The keel, for example, would still be 21 inches square, but the stem would be 15 inches sided and the sternpost 12 inches. There were also specific instructions (very well considered, for the most part) about details of fastening, timber overlaps, etc.

6. Hybertsson replied in early January that he could not follow the king's command, since he could not build a larger vessel (meaning the new 120 foot LOK spec) with the timber already cut for the smaller type, and could not cut down the timber for the larger contract type without significant economic harm to himself. He also reported that he had conducted a detailed survey of the timber he had on hand, and that this was sufficient to build a smaller ship and a larger ship. He does not explain why he thought in September that had anough timber for two smaller ships but now only enough for one, although it could be that some timber had been consumed in fitting out Tre Kronor or in repairing ships damaged in the autmun storms. But in any case, he believed that in January, before he had laid the keel for Vasa, that he had adequate timber for either a larger or smaller ship of the 1625 specification.

7. The king replied that Hybertsson should follow his new instructions, but if "he could not or would not," he was to follow the terms of the contract as signed. This meant to build the a ship of the larger class (128 feet LOK) first.

8. In early March 1626, Hybertsson was called to a meeting with the chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, to account for his actions. At this meeting, he explained the same issues he had tried to explain to the king, and that he had followed the terms of the contract (as the king had eventually agreed) and that the keel for the first vessel had been laid (thus probably in later February or early March), but noted that it would differ slightly from the specification. We can see that the actual keel length differs slightly in length from the spec for the larger ship, by less than 2%.

9. After the keel was laid, there was no further discussion in the official correspondence about the size of the ship or its specification, nor any change orders. What discussion there was of Vasa largely focused on the armament plan, which was a debate that covered a wide range of possibilities and was not settled until after the hull was complete. The changes made to the ship during construction do not seem to have required royal approval, but could have been initiated or approved by the navy's "project officer", a senior captain supervising the private contractors at the navy yard.

If we compare the actual dimensions of Vasa's timbers to the specification for Tre Kronor, the proposed model for the smaller ship, and to the king's proposed "medium" ship of 120 LOK, we can see that almost all of the actual timber dimensions in the ship as built, from the very first timber laid down, are measurably larger than the timber used in Tre Kronor (and thus the spec for the smaller ship class of the 1625 contract) or specified for the king's altered spec. It is thus very difficult to see how one could say that Vasa is built from timbers originally designed/cut for a smaller ship. Which smaller ship?

I would still agree that the design of Vasa is basically an enlargement of a design for a smaller vessel, since that is the starting point Hybertsson had in his experience.

As for the extreme pressure from the king, this is largely overdriven in some modern studies. There is no evidence that the king pushed Hybertsson to finish the ship ahead of schedule, and after the discussion of size in the autumn of 1625, the king eventually accepted Hybertsson's explanation of the limitations imposed by the timbers already cut, and allowed him to follow the terms as laid down in the contract without further interference. It then took about 18 months to complete the hull, which is not a rush job in a 17th-century shipyard run and manned by Dutch shipwrights.

Where the king's pressure did come to bear was on the supply of armament. The foundry in Stockholm was very slow in filling the order for an entirely new armament of 72 bronze guns, and Vasa sat idle for a year after the ship was substantially finished before there were enough guns to arm it. Gustav Adolf pulled a number of strings and interfered significantly to try to get the ship armed in time for the 1628 campaign season, a year after it should have been in service, and even then it sailed eight guns short of its mandated armament.

Fred

.

OK, maybe the circumstances surrounding the use of a set of small/short timbers instead of large/longer timbers will no longer be recognised (although the pressure, compounded further by the disaster of 1625, must have been immense), but I very much want to show in an evocative, graphic way that it would have been enough even to design (or perhaps better: build) Vasa 1628 like any other ship, and importantly – including single-decked ones, according to general, well-known and widely used design principles, to produce a perfectly successful, at least in a hydrostatic sense, vessel. This actually should still be in my previous post.

Edit:

Ah, language, as a (precise) communication tool, almost always fails, despite efforts. For example, when I spoke of pressure to speed up the work, I meant not so much to build faster, but more – to start construction without undue delay.

.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2021

- Messages

- 143

- Points

- 143

I agree, the yard was under some pressure in the autumn of 1625 and winter of 1626 to get started on the first ship, which Hybertsson did manage to do, even after the discussion of a potential specification change. I think that there was also some economic pressure on Hybertsson, as the crown had not been able to keep up its end of the contract and make payments on time, and inflation during 1625-1628 meant that the ship ended up costing about 30% more than the contract price, an overrun that the contractor had to eat..

I think Waldemar is correct, that there were some well established design principles that were not used in Vasa. I am curious about what defines "normal" in this case, since different builders used different sorts of proportions. Who, for example, stated that depth should be one tenth of length?

Vasa is certainly too shallow for its length in any case, and a graphic presentation of this would be very useful.

Fred

I think Waldemar is correct, that there were some well established design principles that were not used in Vasa. I am curious about what defines "normal" in this case, since different builders used different sorts of proportions. Who, for example, stated that depth should be one tenth of length?

Vasa is certainly too shallow for its length in any case, and a graphic presentation of this would be very useful.

Fred