.

Many thanks Fred

@fred.hocker for taking a look and your always valuable commentary.

I would like to address a couple of points raised.

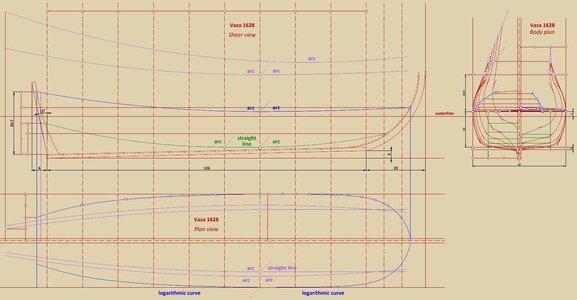

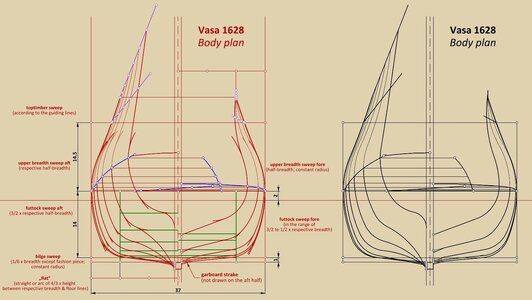

Regarding the presence of dead flat in the central part of the hull, I must admit that finding the original design lines solely on the criterion of a potentially locally deformed curvature of the hull shape would indeed be a rather slippery undertaking. I therefore personally use a different, much more reliable method in such cases. For example, I try on various types of curves as line of the floor or line of the greatest breadth (e.g. arcs of circles, ellipses, logarithmic curves, etc.), move them along the hull and also modify their specific run and observe the differences in the distances between all the respective co-ordinates of these lines and the co-ordinates read from the source. In this way, the whole shape of the hull, not just some isolated and potentially deformed section, is involved in determining the run of the design lines. Incidentally, this is usually a rather tedious, multi-iteration procedure, but it is difficult to find another that is as effective.

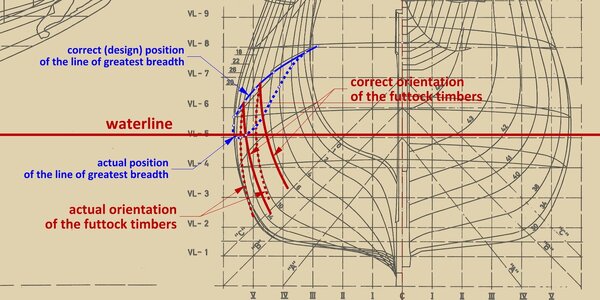

The issue of canted frames on

Vasa is also interesting. The point is that a slight, a few degrees inclination of the frames does not change the shape of the hull in any fundamental way. Thus, it is possible to imagine a situation where frames designed in vertical orientation were later actually erected at a slightly different angle (and even intentionally, e.g. for better correlation with decks or gun ports), and this with virtually no noticeable detriment to the ship's nautical properties. Actually, one don't even need to imagine this, because it was actually the case: especially in 18th century France (but also elsewhere and at other times), ships were quite commonly designed on level waterline (and thus with a sloping keel) and with vertical frames, but later, during actual construction, the frames were put vertically on the keel without reprojecting them for the resulting slightly different angle. My friend Martes and I have been looking for evidence of such reprojecting for very many months now (especially Martes has been particularly persistent on this matter), but so far we have not come across even one such case either in the French detailed treatises on naval architecture or among the dozens or even hundreds of plans we have reviewed for this. Apparently no one bothered with a difference measured in a few inches at most, and even then in the least important, highest parts of the hull.

Certainly, I do not know how it was in the specific case of

Vasa 1628, but for the above reason, and several others, the mere fact of skewed frames on this ship does not, in my opinion, exclude the possibility of using previously drawn plans, partial or even complete. Such a plan could have been produced either on a reduced scale, on paper, or immediately in actual size on the mould loft in the shipyard. Personally, I do not subscribe to the view of the widespread use of paper plans in this period, but since paper plans were successfully used in later periods, what in practical terms could preclude their use earlier? I believe that the breakthrough in the widespread use of paper plans was only the introduction of diagonals and waterlines, both design and smoothing. It was simply no longer possible to proceed without paper, unlike in the earlier, 'non-corrective' methods.

Is it possible to design and build in an engineering way without using scale plans? Absolutely, especially if one takes into account hundreds, if not thousands of years of collective routine. For example, now, with some experience in the field myself, I don't need to know the contours of the frames to at least roughly judge the character of the ship, a glance at the longitudinal design lines is enough. And these longitudinal design lines can be perfectly simulated on the end view on the mould loft by some graphic devices like

mezzaluna or similar.

As one becomes familiar with more and more material, the prevailing trend of using a couple of leading frames along the length of the hull becomes more and more apparent in the Northern tradition of this period, whereby the divisions practically used (that is, the specific number of divisions or even the divided element – the keel or, for example, the horizontal length of the line of the floor), could be quite individual in specific cases.

Artillery is also an interesting topic. Today, indeed, there is a great deal of emphasis on range when evaluating the capabilities of the guns of the past, but it is probably best to cite the example of Nelson and several other admiral-professionals who were quite cognisant of the effectiveness of firing from greater distances, always insisting on maximal shortening it at all costs, with the murderous efficiency we know. And battles fought at distances measured in many hundreds of metres ended with, at most, "a few sticks broken and a tooth knocked out".

However, I was more concerned with the weight of the cannons on the

Vasa 1628. These 24-pounder

half-kartauns have only the weight of fairly typical 12-pounder cannons, which means that after just a few shots fired in rapid succession a pause had to be made, otherwise various accidents would occur and even the guns themselves would be damaged beyond repair due to overheating. Not to mention the insane recoil of such lightweight guns (one can almost compare them with carronades). It is no coincidence that already shortly after the doctrinal adoption of gunnery tactics (replacing the hitherto dominant boarding tactics) during the First Anglo-Dutch War, drake-type guns, very similar in nature to the lightweight

half-kartauns on

Vasa, fell rapidly out of favour and were hastily re-cast into normal weight guns, in all fleets. The requirements in the field artillery could be a little different, as for the sake of sheer manoeuvrability they were often reconciled to a certain loss of tactical properties of the guns.

But what I really meant was that it was probably already realised at the time of building

Vasa 1628 that fitting normal

half-kartauns, i.e. of a typical weight for this calibre, on the ship was simply not possible or at least unsafe, hence the decision to cast a huge batch of a few dozen at a time, modelled after the field artillery specimen, specifically for the

Vasa. Unfortunately (or should I say, fortunately

), it didn't help anyway...

Waldemar

.