- Joined

- Mar 11, 2020

- Messages

- 170

- Points

- 143

The Zeehaen, a Dutch fluit used by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. But first some historical background information of a Fluit.

Shipbuilders, skippers and other curious people, from near and from far, travelled to Hoorn in Noord Holland to look at the new ship. A prominent merchant, Pieter Janszoon Liorne, had turned his view of the ideal merchant vessel into reality. By the end of the sixteenth century there existed a ship type called a fluit, which had some specific characteristics.

Seen from the side a fluit looks just like any old three-masted sailing ship. The mainmast and the foremast have square sails and the aftermost mizzenmast has a triangular lateen-sail occasionally supplemented with some smaller sails on the bowsprit and mizzenmast.

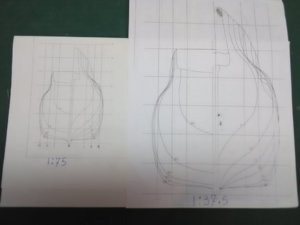

The particularities of the fluit’s hull become apparent when seen from above or from astern. From above the outline of the hull appears as a rectangle box with slightly rounded corners. Seen in cross section the sides of the hull slope inwards, so-called ‘tumble-home’, which result in very narrow upper works. The rounded lower parts of the stern are crowned by a narrow flat transom, giving it a pronounced pear-shape. It might be that this shape, which stern-on gave the impression that the after works looked something like a thinly shaped glass, a flute, is the origin of the name.

The Dutch fluit was a classic merchant ship of the 17th century. It was built to be economical in operation, carrying the largest cargo and smallest crew possible. The rigging was designed to be sailed and operated with proportionally small crews (12 to 13) , and its narrow upper deck was designed to evade Danish customs dues when passing through the sound in to the Baltic, where duties were levied according to the size of the breadth of the deck.

There are several reasons for building a hull of this shape. Keeping the center of gravity low is perhaps the most obvious. The idea that the hull shape of the fluit was adjusted to cut costs probably derives from the general reputation of the Dutch merchants at the time. Creating a ship type that kept costs to a minimum becomes just another way to confirm their superiority and skill when it came to making profit.

The fluit was a total success. From the end of the 16th century to the mid 18th century fluits were amongst the most common type of merchant vessels in Northern Europe and the Baltic Sea. In the Dutch Golden Age, 80% of the ocean going vessels were fluits and were built at an average of 400 to 500 annually. They were easy and cheap to build thanks to standardization of design as well as a technological improvements, such as the sawmill, which was invented by the Dutch.

The fluit was a ‘multi-purpose’ vessel, a ship that with slight adjustments could meet a wide range of demands. Even if the term embraces a range of ships which share some important characteristics, there are variations with important differences. The size of fluits varied considerably. The smallest versions, sometimes referred to as the boot, were 86 feet at most (around 24m), whereas the largest versions were 140 feet (just over 39 m) and larger. Variations of the basic concept did not only affect the size, but included some special features connected to the trades in which these ships were used.

Noortsvaarders or Houthaalders - Woodhauler was developed with ports in the bow and stern for loading long beams and timbers, They were of about 300-350 tons, with simple hulls and an armament of small guns.

Ostervaarders, especially designed for the shallow harbours of the Baltic Sea.

Fransvaerders, Spaensvaerders and the Straetsvaerders, so called because they were used in the trade with France, Portugal or Spain and the Mediterranean (through the straits). From the exterior, they differed from the other varieties through the beakhead

The Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC, (United East India Company), employed a number of fluits.

Fluits were also used as whalers which are easy to distinguish in depictions as they have davits on the sides for lifting whaling boats.

Next, a biography about Abel Tasman

Shipbuilders, skippers and other curious people, from near and from far, travelled to Hoorn in Noord Holland to look at the new ship. A prominent merchant, Pieter Janszoon Liorne, had turned his view of the ideal merchant vessel into reality. By the end of the sixteenth century there existed a ship type called a fluit, which had some specific characteristics.

Seen from the side a fluit looks just like any old three-masted sailing ship. The mainmast and the foremast have square sails and the aftermost mizzenmast has a triangular lateen-sail occasionally supplemented with some smaller sails on the bowsprit and mizzenmast.

The particularities of the fluit’s hull become apparent when seen from above or from astern. From above the outline of the hull appears as a rectangle box with slightly rounded corners. Seen in cross section the sides of the hull slope inwards, so-called ‘tumble-home’, which result in very narrow upper works. The rounded lower parts of the stern are crowned by a narrow flat transom, giving it a pronounced pear-shape. It might be that this shape, which stern-on gave the impression that the after works looked something like a thinly shaped glass, a flute, is the origin of the name.

The Dutch fluit was a classic merchant ship of the 17th century. It was built to be economical in operation, carrying the largest cargo and smallest crew possible. The rigging was designed to be sailed and operated with proportionally small crews (12 to 13) , and its narrow upper deck was designed to evade Danish customs dues when passing through the sound in to the Baltic, where duties were levied according to the size of the breadth of the deck.

There are several reasons for building a hull of this shape. Keeping the center of gravity low is perhaps the most obvious. The idea that the hull shape of the fluit was adjusted to cut costs probably derives from the general reputation of the Dutch merchants at the time. Creating a ship type that kept costs to a minimum becomes just another way to confirm their superiority and skill when it came to making profit.

The fluit was a total success. From the end of the 16th century to the mid 18th century fluits were amongst the most common type of merchant vessels in Northern Europe and the Baltic Sea. In the Dutch Golden Age, 80% of the ocean going vessels were fluits and were built at an average of 400 to 500 annually. They were easy and cheap to build thanks to standardization of design as well as a technological improvements, such as the sawmill, which was invented by the Dutch.

The fluit was a ‘multi-purpose’ vessel, a ship that with slight adjustments could meet a wide range of demands. Even if the term embraces a range of ships which share some important characteristics, there are variations with important differences. The size of fluits varied considerably. The smallest versions, sometimes referred to as the boot, were 86 feet at most (around 24m), whereas the largest versions were 140 feet (just over 39 m) and larger. Variations of the basic concept did not only affect the size, but included some special features connected to the trades in which these ships were used.

Noortsvaarders or Houthaalders - Woodhauler was developed with ports in the bow and stern for loading long beams and timbers, They were of about 300-350 tons, with simple hulls and an armament of small guns.

Ostervaarders, especially designed for the shallow harbours of the Baltic Sea.

Fransvaerders, Spaensvaerders and the Straetsvaerders, so called because they were used in the trade with France, Portugal or Spain and the Mediterranean (through the straits). From the exterior, they differed from the other varieties through the beakhead

The Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC, (United East India Company), employed a number of fluits.

Fluits were also used as whalers which are easy to distinguish in depictions as they have davits on the sides for lifting whaling boats.

Next, a biography about Abel Tasman